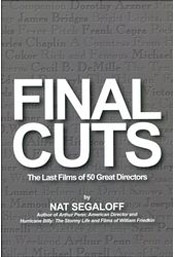

(BearManor Media, 350 pages, $24.95)

By Nat Segaloff

In a business where you’re only as good as your last film, it is surprising to learn that the final works of cinema’s greatest directors are often shrouded in mystery and relegated to the outskirts of their oeuvres. Why have these films remained in relative obscurity? Are they simply misfires that have been prudently brushed under the rug? Such questions are examined in Nat Segaloff’s Final Cuts: The Last Films of 50 Great Directors.

His concept is deceptively simple; he looks at 50 of the last century’s most prominent directors (living directors are obviously precluded) whose body of work made a lasting impact on filmmaking. Admittedly, many of the final films in Segaloff’s study were rife with behind-the-scenes complications that took a toll on the production: whether personal, financial, health-related, or more often than not, the result of studio interference.

For example: The mythic legend of Charlie Chaplin was left scarred by his 1967 disaster A Countess From Hong Kong. Filmed while he was in exile from the United States, it spiraled into an embarrassing farewell to filmmaking from the man who had helped define cinema itself. By the time John Ford made 7 Women in 1966, many of the younger employees on the studio lot had to be told who the 71-year-old legend was. Ford labored with doubts about performance throughout the shoot, but his biggest doubt was in his place in a world that had vastly changed since his earlier work. He was afraid the film would mark the end of his career, and it did.

But Segaloff’s book is hardly a ‘how the mighty fallen have fallen’ dirge, as a number of directors ended their careers on a high note. Most notably, perhaps, is Cecil B. DeMille with his 1956 biblical epic The Ten Commandments, which not only garnered multiple Academy Award nominations, but also remains something of a seasonal staple to this day. Also cited is Robert Altman’s A Prairie Home Companion, a strikingly visual film that performed respectably both commercially and critically.

Segaloff’s underlying lesson in this entertaining, yet sometimes sobering undertaking, is that perhaps directors would do well to treat each film they make as if it was their last.

Review written by Carley Johnson