By David Davis

As Usain Bolt, Michael Phelps, and the world's best athletes set their sights on the gold in London at the 30th Summer Olympic Games, a team of highly skilled and experienced directors will be trying to hit their own marks with a record amount of coverage. The stage is set for 17 consecutive days and nights of sprints, dives, digs, jumps, and opening and closing night spectaculars.

"The Olympics transcend sports," says Brent "Bucky" Gunts, NBC's coordinating director for the London Games. "They're unique in that they always produce special moments and surprises. There is no other event that compares in sports television."

The challenge facing Gunts will be to top the Beijing Olympics four years ago. From July 27 through Aug. 12, the network will air a record 5,535 hours of action on NBC and its myriad platforms, including MSNBC, CNBC, Bravo, Telemundo, the NBC Sports Network, and NBCOlympics.com. NBC alone will air 272.5 hours, a 21 percent increase from Beijing.

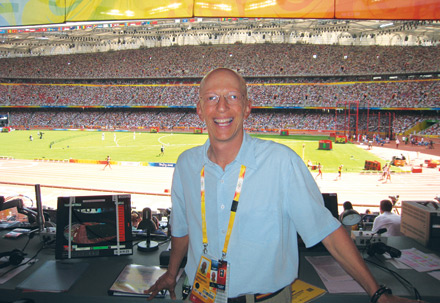

BRITISH INVASION: (top) The beach volleyball competition, directed by Jeff Simon, will take place in historic Horse Guards Parade in the heart of the city. (bottom) Bucky Gunts, back for his 10th Olympics, is NBC’s coordinating director for the London Games. (Photo: (top) Getty/(botttom) NBC Universal)

BRITISH INVASION: (top) The beach volleyball competition, directed by Jeff Simon, will take place in historic Horse Guards Parade in the heart of the city. (bottom) Bucky Gunts, back for his 10th Olympics, is NBC’s coordinating director for the London Games. (Photo: (top) Getty/(botttom) NBC Universal) "We've expanded the number of hours and we're going to be streaming everything live," says Gunts. "The biggest change for us in London is the introduction of NBC's new sports cable network. That'll be on 16 hours a day, with a lot of basketball and soccer action. We expect to drive a lot of eyeballs there."

A recipient of the DGA Award for Lifetime Achievement in Sports Direction, Gunts is returning for his 10th Olympics. He will coordinate coverage with nine event directors at London's far-flung venues and nine studio directors (several of whom will be based in New York) to determine what story lines NBC will highlight and which athletes the network will feature. As he prepares for any conceivable disaster—from a terrorist attack to London's notoriously changeable weather—Gunts has assembled an event-tested crew that knows how to handle the pressures of directing live sports on the world's biggest stage and finding the drama in the events.

"We've got the perfect people in place at the biggest venues, with Andy Rosenberg on track and field, Drew Esocoff on swimming, David Michaels on gymnastics," says Gunts. "We know that there's going to be at least two or three things that will happen that you least expect. That's the great thing about the Olympics. There's a lot that's unpredictable."

The sweeping drama and spectacle of the Olympics has captivated directors since 1908, when film pioneers the Pathé Brothers produced the first significant motion-picture footage of Olympic action. The snippets of film shown at theaters and nickelodeons around the globe cemented the Olympics' reputation as the foremost international sports competition. Years later, Leni Riefenstahl mined the 1936 Berlin Games for her groundbreaking propaganda documentary Olympia; Japanese director Kon Ichikawa made Tokyo Olympiad, a quiet masterpiece about the 1964 Summer Olympics; and eight directors, including Arthur Penn, Milos Forman, John Schlesinger, and Claude Lelouch, captured the 1972 Munich Olympics in Visions of Eight.

For broadcast rights to the 2012 London Olympics, NBC's then-parent company General Electric paid a record $1.18 billion. Gunts notes that, for the first time, all events will be streamed live over the Internet; viewers will be able to watch the entire Olympic programming slate via their laptops and iPhones. There will even be an exclusive channel for those with 3-D television sets.

The Olympics fortnight is normally so intense and crammed for the directors that shooting for new media platforms probably won't affect their already lengthy day very much. "When we cover the events, the directors are covering them as if they're live anyway," Gunts says. "They might have to do some editing or fixes later, for the primetime show, but this won't really change anything for our directors."

Gunts has served as head of production for NBC's Olympic coverage since the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics. (He likes to joke that he has seen only one event in person.) His preparations for London grew intense shortly after the close of the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics. Gunts has made multiple trips to England to scout venue locations and to coordinate production details with the International Olympic Committee, the broadcast entity that oversees the Olympics and provides the "world feed" to each country's broadcast rights holders.

"Bucky is the main cog in the entire operation for NBC," says John Gilmartin, who will direct the late-night studio show from London. "He played a vital role in all of the camera locations and setups, for the remotes and for the sets that were built inside the broadcast center. It's a huge amount of work and responsibility."

"Bucky makes everybody's job easy," says Esocoff. "He is so passionate about the Olympics. He puts you in a position to succeed as a director, and if you don't succeed you have nobody to blame but yourself."

The four-hour, primetime opening ceremony, featuring 12,000 cast and crew members, is being directed by DGA Award winner Danny Boyle (Slumdog Millionaire), while Stephen Daldry (Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close) is the producer of the opening and closing ceremonies. According to Boyle, he was inspired by Shakespeare's The Tempest as well as Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

Details of the show, entitled "Isles of Wonder," remain a well-kept secret, including which athlete will light the Olympic cauldron. The challenge of staging such a ceremony, Boyle said in one interview, is that "it can easily be just a cold spectacle—awe-inspiring but not necessarily of the heart—and we want the ceremony to have a visceral effect on the people, for it to be a collective experience. Stirring emotion is hard in a stadium."

The London opening, according to Gunts, will be very different from the $100 million, jaw-dropping spectacular that jump-started the 2008 Beijing Olympics, directed by Zhang Yimou. Boyle and Daldry, Gunts says, are "going to bring a very different approach. I can't tell you specifics, but imagine yourself watching a Danny Boyle movie: it's fast-paced, it's electric, it's audio-driven with a great soundtrack. Danny is a proud Londoner, and it shows. There will be plenty of ‘wow' moments."

Gunts himself will handle the NBC directing duties for the opening. The show is estimated to reach 1 billion global TV viewers. "The opening ceremony is very important because it sets the tone for NBC's broadcasts," says Gunts. "We want it to be uplifting, to get people in the Olympic frame of mind."

Gunts plans to capture those moments using approximately 75 cameras, about 25 of which belong to NBC. The other shots will come from the world feed's cameras. Of these, Gunts has two options: He can take the integrated feed—which is the edited version of the show—or he can access splits from individual cameras. "It's a little bit risky, because you don't control those cameras and you're not sure where they're going," Gunts says. "I'll end up doing the parade of nations unilaterally, so I can follow our announcers [primetime host Bob Costas and the Today show's Matt Lauer] rather than be at the mercy of the world feed."

Once the Games start, Gunts will concentrate on his second job: directing the nightly three-hour primetime show for NBC. "This whole [production] group has done it together for a long time," he says. "I can focus on the opening ceremony and just be confident that when we get to the primetime show the next day, we'll be ready to go."

That coverage will revolve around the studio sets constructed within the International Broadcast Center: one used exclusively for the nightly primetime show that Gunts directs, and another shared by the two afternoon directors (Michael Sheehan and Kelly Atkinson) and the late-night director (Gilmartin). The spaces are small, but each director will have use of two hard cameras, a jib (Technocrane), and a Steadicam. The primetime studio features a 103-inch plasma monitor placed behind Costas for graphics, and a massive 152-inch screen will display highlights and other images.

The afternoon and late-night sets use a huge wall monitor with 28 individual video cubes that can be manipulated to show one image or 28 separate pictures, including replays and in-studio interviews with athletes. "It's a new way of showing things," Gilmartin says. "We're trying to keep it fresh by incorporating the latest in technology."

Adds Gunts, "We have used the Olympics consistently as a platform to roll out new technology. So we'll have plenty of nice toys to work with in the IBC [Production Village]. "

Outside the IBC, Gunts will have his crew of veteran directors at key venues throughout London. Doug Grabert will direct the high-flying diving events, using a new device called the "Splashometer" to measure the actual splash of each diver. Joe Martin will direct a flash unit for road races and the triathlon. One unit will be based at Wimbledon for tennis, and another will be on standby for breaking news. Here's how directors will approach some of the signature events.

WATER WORLD: (bottom, center) Drew Esocoff will command as many as 10 cameras for events at the newly built London Aquatics Center to follow the (top) Michael Phelps story as he tries to repeat his "unbelievable, once-in-a-lifetime" feat of winning eight gold medals. (Photo: (top) Everett/(bottom) NBC Universal).

WATER WORLD: (bottom, center) Drew Esocoff will command as many as 10 cameras for events at the newly built London Aquatics Center to follow the (top) Michael Phelps story as he tries to repeat his "unbelievable, once-in-a-lifetime" feat of winning eight gold medals. (Photo: (top) Everett/(bottom) NBC Universal). Esocoff handled the swimming chores in Beijing and will do the same in London. One of the biggest stories he followed in Beijing was Phelps' quest for eight gold medals. "That was unbelievable, a once-in-a-lifetime event," he says. "People have memories of those magical days at the Water Cube in Beijing. Maybe it'll happen again."

Esocoff will command as many as 10 cameras for events at the newly built London Aquatics Center, including four hard cameras and two handhelds on the deck of the pool. He plans to mix in the world feed, which provides the underwater and overhead cameras. Two graphic markers—the flag lane, which identifies the swimmers as they churn through the water, and the world-record line, which tells if a competitor is ahead or behind of record pace—will also be supplied by the world feed.

But Esocoff is wary of leaning heavily on what he calls "all the gimmick cameras [because] as a director, you want to show who's in the lead, who's in second, who's in third. When you start getting over-aggressive with the underwater cameras, it can be very disorienting. The biggest challenge as a director is to layer in the gimmick cameras without losing sight of the fact that a swimming event is a race."

Likewise, Esocoff understands that his audience watches swimming only once every four years. "You have to make sure that you don't put anything on television thinking that everybody knows what you're talking about," he says. "You can't assume that the same people who were watching on Tuesday night are also watching on Thursday night. You've got to educate everybody every night."

Unlike in Beijing, when most of the swimming events were shown live, the majority of the contests in 2012 will be broadcast on tape delay. That won't make much of a difference in terms of how he directs, says Esocoff. "I tell everyone on our crew, ‘we need to be as focused as if this were live,' because anytime you start doctoring live sports, it never looks as good and never sounds as good. If you make a mistake and you have to do a fix, you do a fix. But we approach this as if there are no fixes."

HORSING AROUND: (bottom) David Michaels will be stationed in a truck parked outside the North Greenwich Arena for the gymnastics events. One of the things he learned from covering Paul Hamm (top) winning the all-around gymnastics title in 2004 is the importance of staying with the shot. (Photos: (top) NBC Universal/(bottom) Corbis)

HORSING AROUND: (bottom) David Michaels will be stationed in a truck parked outside the North Greenwich Arena for the gymnastics events. One of the things he learned from covering Paul Hamm (top) winning the all-around gymnastics title in 2004 is the importance of staying with the shot. (Photos: (top) NBC Universal/(bottom) Corbis) The gymnastics competition, which aired live from Beijing, will also be on tape from London. According to director Michaels, the fact that viewers know which athlete has won beforehand doesn't curtail the excitement surrounding gymnastics, which typically earns huge ratings for NBC. "The erroneous assumption about Olympic programming is that all people care about is results," he says. "That may be true with the Final Four or with the NFL. With gymnastics, you can hear that so-and-so won the gold medal, but that may or may not be the most compelling story. Watching how the story evolves is often more interesting than reading about it on the Internet."

In London, Michaels will be stationed in a truck parked outside the North Greenwich Arena. He plans to use 10 unilateral cameras: five handhelds that rove the floor between the different apparatus, as well as five hard cameras in the stands for the more telephoto look. He then mixes those shots with the world feed's 25 cameras. "I use more close-ups and more intimate handheld shots from the stands," says Michaels. "It's just a different coverage style. The world feed may use one camera for a routine on the pommel horse. I know that at the beginning of a routine, I want to see the hands on the top of the horse and then, during the second half, I want to see it from down low to see whether they're banging into the horse."

That style, he says, "brings an incredible level of intimacy. We're literally next to the gymnasts when they're competing and waiting for their scores. There's nothing like it. I think that's why so many people tune in—because all the athletes look so vulnerable. They're out there running around in their underwear. They're naked before you."

His experience shooting gymnastics and figure skating for the Winter Games has trained Michaels to expect the unexpected. It helps that he has been shooting with the same crew since 2000. "We've learned to be prepared for every eventuality," he says, "because the Olympics will throw everything possible at you. In Beijing, I looked up and all of my handhelds had disappeared from the monitor wall while we were in commercial. I thought, ‘Hell, what am I going to do now?' Luckily, they found that it was some antenna that had screwed up, and I was able to work around it."

Like his Olympic colleagues, Michaels embraces patience in directing live sports. "TV directors are always in a hurry to get to the next shot: ‘Take four, take three, ready camera five, take five,'" he says. "But sometimes they're cutting away at the most inopportune moments. I've learned to know that these shots are going to evolve. Like, in 2004, when Paul Hamm won the all-around [gymnastics title]: I stayed with camera seven for probably a minute and 20 seconds because the cameraman was making an incredible shot and telling an amazing story. I didn't need to change cameras because everything was changing in front of me."

FAST TIMES: (bottom) Andy Rosenberg’s cameras turned Usian Bolt’s 9.6-second world record (top) in Beijing into an Olympic legend. (Photo (top) Andy Rosenberg/(bottom) Everett)

FAST TIMES: (bottom) Andy Rosenberg’s cameras turned Usian Bolt’s 9.6-second world record (top) in Beijing into an Olympic legend. (Photo (top) Andy Rosenberg/(bottom) Everett) For the all-important track and field events, Gunts will again turn to Rosenberg. Inside the Olympic Stadium, Rosenberg plans to employ about 20 cameras, including two head-on super slo-mos, several handhelds, and one high-speed camera for selected events. He, too, will integrate material from an additional 30 cameras from the world feed. But all the cameras in the world, Rosenberg says, won't help an unprepared director. "Directing live sports is unique to television. It's not a sitcom, it's not scripted. You plot and plan—you have your cameras where you want them and you know everyone who's in the race—but then you have to react to the moment. As soon as you say, ‘Take two,' as opposed to, ‘Take five,' that camera is on the air and that's what the person at home is experiencing. It's your responsibility to bring the viewer the right moment at the right time."

As an example of this, Rosenberg relates his experience tracking the Bolt story in Beijing. He was watching anxiously from the control room as Bolt pranced onto the track before the 100-meter finals. He instructed his cameraman with a handheld to pan the runners' faces. As the camera prepared to move away from Bolt, Rosenberg yelled, "No, stop! Stay on him!"

What Rosenberg saw was something that he had never encountered in all his years directing sports television. "All the other runners had that intense look on their faces and they're pumping their arms," says Rosenberg, "And here's Bolt with this big, goofy smile. I've never seen an athlete just before the moment of competition be as loose as this guy."

Rosenberg stayed with the shot until the runners settled into the starting blocks. At the gun, he switched shots from the handheld to the finish line camera in the stands to capture Bolt as he streaked down the track and shattered the world record. Rosenberg's cameras focused on the sprinter as he celebrated the moment, replaying the event in super slo-mo and from different angles, including the rail camera. By the time the evening was over, Rosenberg's cameras had turned Bolt's 9.6-second romp into Olympic legend.

According to Rosenberg, TV directors are required to "document sports"—that is, to show who wins each race. But the top directors tease out the drama within the moment, "capturing the contrast of emotions in victory and defeat," he says. In Beijing, after one competitor was disqualified from the 200-meter race, Rosenberg directed his cameraman to wait for the competitor who had suddenly become a medalist. "We approached him and said, ‘You've just won the bronze medal.' He said, ‘What?' We got this great reaction—live—because we stuck around until the end of the story."

Can London top that? Much of the track and field coverage is again expected to revolve around Bolt, who won three gold medals and set three world records in Beijing. To "get intimate with speed," Rosenberg leans on the rail camera, which travels alongside the runners as they race down the track. Rosenberg helped conceptualize that device in 1988, after the Carl Lewis-Ben Johnson duel in the Seoul Olympics' 100-meter sprint turned into one of the most controversial races in sports history.

He was not satisfied with how the hard cameras, which typically pan 30 degrees during the 10-second race caught the action. "I wanted to bring the viewer closer, because there's an intimacy if you're right on top of something. I said to [aerial photographer Matthew] Allword, ‘What if we can get a camera to run alongside Ben Johnson and Carl Lewis?'"

At the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, NBC unveiled the rail camera, sitting about two feet off the ground, to travel at a speed of just over three meters per second. "From a finish line camera, you can gauge who's ahead, but you're looking at the runners from 70-80 meters away," Rosenberg explains. "With the rail camera, you're running side by side with the runners. You can see their size and their athleticism. I think it's the most exciting shot in track and field." And one that he will make ample use of in London.

Jeff Simon expects beach volleyball to be a colorful event for TV. (Photo: NBC Universal)

Jeff Simon expects beach volleyball to be a colorful event for TV. (Photo: NBC Universal) Jeff Simon, back for his 10th Olympics, will direct the ever-popular beach volleyball events. He will have six cameras of his own: three hard cameras, including one in the stands at center court and two in the end zones on either side of the net; two handhelds on the sand; and a robotic mounted for scenic shots. He plans to combine those with the seven world-feed cameras, including two super slo-mo cameras that he uses for replays.

With beach volleyball matches scheduled for three different sessions every day, Simon is prepared for a lot of action in a short, intense period of time. He's grateful that many of his cameramen worked alongside him in Beijing. "I have a veteran, talented crew," he said. "They've shot the biggest sporting events on television, from the World Series to the Stanley Cup. For something like this, you want people who are used to big events and the craziness of the Olympic schedule."

The beach venue is a temporary one tucked into historic Horse Guards Parade. Simon says the location will provide a novel, dramatic backdrop to the athletes in their beachwear. "It's a tremendous spot in the heart of London," Simon says. "Everything is right there: Trafalgar Square, the House of Lords, Westminster Abbey, Big Ben, Buckingham Palace. Combine that with the fans that beach volleyball draws, it's going to be a colorful scene that will play well on television."

As Gunts and his crew of directors get ready for London, they know that they will be documenting history in the making and creating the next Olympic legends. What they don't know yet is who exactly those heroes will be, and what their stories will be.

"We're always very prepared going in," says Gunts. "We know the story lines that we think are going to happen. But there are at least two or three things that happen at the Olympics that you just don't expect. It never fails. And, hopefully, we'll react well to it—whether it's a news story or just some guy that came out of nowhere to win an event. That's the great thing about the Olympics. There's a lot that is unpredictable, but it always delivers."