BY TERRENCE RAFFERTY

Photographed by Scott Council

Sam Peckinpah was probably the greatest, and surely the most influential, director of action in the past half-century of movies: a virtuoso of speed, chaos, the intimate blur of violence. When his fourth feature, The Wild Bunch, invaded movie theaters in the summer of 1969, audiences were stunned, and in some cases appalled, by the ferocity of the bloodletting in its opening sequence, in which dozens of residents of a sleepy Southwestern town are slaughtered in the crossfire between a gang of bank robbers and a trigger-happy posse of bounty hunters. The cutting is disorientingly fast and the sound of gunfire is deafening, constant, deranging, but many of the deaths happen in eerie slow motion, suspended in time like the worst moments in a very, very bad dream. Those viewers who stayed to the end of the film saw a climactic massacre yet even more prolonged and hallucinatory, with a staggering body count and editing of such dizzying complexity that no mind in the audience remained unblown.

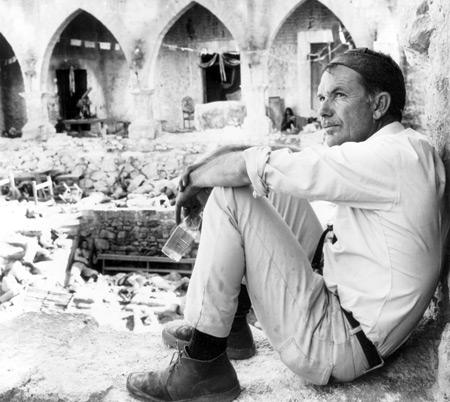

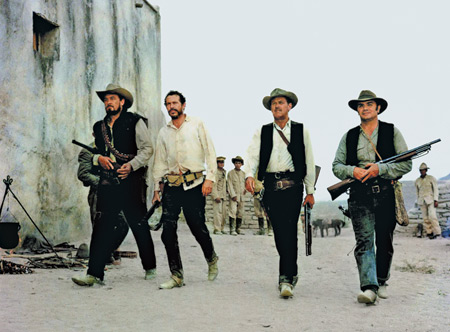

ODD MAN OUT: In between the mayhem, Peckinpah catches his breath on the set of The Wild Bunch. He was by temperament a man who liked to stir things up (photo courtesy of Photofest). (bottom, left to right) The Wild Bunch—Ben Johnson, Warren Oates, William Holden, and Ernest Borgnine—make their last stand (photo courtesy of Everett)

ODD MAN OUT: In between the mayhem, Peckinpah catches his breath on the set of The Wild Bunch. He was by temperament a man who liked to stir things up (photo courtesy of Photofest). (bottom, left to right) The Wild Bunch—Ben Johnson, Warren Oates, William Holden, and Ernest Borgnine—make their last stand (photo courtesy of Everett) The carnage in The Wild Bunch dominated discussions of the film at the time; it was the Vietnam era, after all, when violence in America was a nearly ubiquitous topic of conversation. Peckinpah, by temperament a man who liked to stir things up, was more than willing to be part of that conversation, but in interviews he would also sometimes protest that the movie was just a simple story about outlaws on the run. And although there's nothing simple, really, about The Wild Bunch, it's worth remembering, from time to time, that the film is in fact a Western, and that its director was himself, as he said, "a child of the Old West." He was born in Fresno, California, in 1925 and "knew at firsthand the life of cowboys. I participated in some of their adventures and I actually witnessed the disintegration of a world." He went on to say, "It was then inevitable that I should speak of it one day through a genre which is itself slowly dying: the Western."

Of the 14 films Peckinpah directed, only six are set in the Old West, and all of them convey that sense of something slowly dying, even when, as in the bookending massacres of The Wild Bunch, the sights and sounds of violence are coming at us faster than we can take them in. The Wild Bunch has more than 3,600 individual edits—a record for color films—but somehow the movie doesn't feel frenetic. Although Peckinpah could unleash havoc when havoc was required, he knew that the West was about space and openness and the freedom to take life at your own pace, to ride through long stretches of emptiness at a walk or a gentle trot and spur your horse only when you have to. And he knew, too, that the Western is essentially a ruminative genre: A man gets to thinking out there in that big lonely country.

That's why, for many admirers of The Wild Bunch, the film's most heart-stopping scene isn't the bloody battle at the end, but the short sequence that precedes it, in which four weary outlaws decide, almost wordlessly, to rescue a member of their gang held captive by a sizable garrison of Mexican army soldiers. "Let's go," the Bunch's leader (William Holden) says, and one of his men says, "Why not?" They all, silently, gather up their weapons and begin to walk—gravely, unhurriedly, four abreast—to their deaths. This is thinking at its most consequential, expressed as action at its most deliberate: The westerner's way. The walk, shot largely with long lenses that give the simple action the shimmer of myth, was improvised by Peckinpah on set. (There's footage of the filming in Paul Seydor's fine 1996 documentary The Wild Bunch: An Album in Montage.) That wasn't unusual for him. He rarely used storyboards, even for the most elaborate sequences, preferring to choose his setups on the basis of the atmosphere he felt on the set when he came to work in the morning, to trust to the inspiration of the moment. When his mind said "Let's go," his eye said "Why not?" and went to work.

Most directors, of course, can't—or won't—operate that way: It's risky, and on a major production it can be time-consuming and expensive. Improvisation, especially in an art as technically demanding as film, depends entirely on the breadth and depth of the artist's experience: The more you have, the better your spur-of-the-moment choices will be. By 1969, Peckinpah had plenty of experience. He began his film career in the mid-'50s as an assistant to the terrific B-movie director Don Siegel (Invasion of the Body Snatchers), and then moved on to television, which, fortunately for him, was at that time crazy about Westerns. After a couple of years writing for Gunsmoke and other series, he got his first directorial assignment in 1958, on a show called Broken Arrow, and later directed episodes of Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theater, The Rifleman, and Klondike. In 1960, at a time when the small screen's love affair with Westerns was beginning to cool, Peckinpah created and produced a wonderful half-hour series called The Westerner, in which an ordinary saddle tramp named Dave Blassingame (Brian Keith) drifts from place to place in the company (sometimes) of his dog, Brown, who's as aimless and unremarkable as he is.

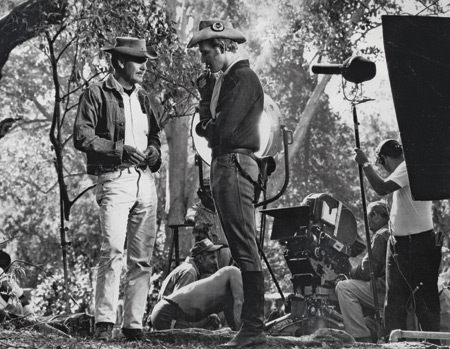

KNOCKIN' ON HEAVEN'S DOOR: (top) The Ballad of Cable Hogue, with Jason Robards and Stella Stevens, was a whimsical respite for Peckinpah (photo courtesy of Getty Images); (middle) Peckinpah works with Richard Harris on Major Dundee; (bottom) Peckinpah with James Coburn in the mythical Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (photos courtesy of Photofest)

KNOCKIN' ON HEAVEN'S DOOR: (top) The Ballad of Cable Hogue, with Jason Robards and Stella Stevens, was a whimsical respite for Peckinpah (photo courtesy of Getty Images); (middle) Peckinpah works with Richard Harris on Major Dundee; (bottom) Peckinpah with James Coburn in the mythical Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (photos courtesy of Photofest) The Westerner, shot in black and white, was—in the spirit of its title—both unassuming and slyly ambitious: Dave Blassingame isn't forced to be emblematic of the Old West, but the small stories of the people he meets on his travels do add up to a kind of portrait of a time and a region, and a way of life that seems to be making itself up as it goes along. Because Peckinpah knew these people, he didn't have to be sentimental about them. In the first episode aired, "Jeff," which was directed and co-written by Peckinpah, the hero wanders into a bleak cantina and finds there a woman he had known, and maybe loved, years before, in the bygone days when they'd both had roots. She has become a prostitute; Dave tries to persuade her to leave town with him and has a fight with her pimp/lover, which he wins—but she decides to stay, and Dave rides out, slowly, with Brown. The Westerner was cancelled after only 13 episodes, of which Peckinpah directed four. The Flintstones was killing it in the ratings.

Peckinpah's technique in the Westerners he directed is, of necessity, a good deal less elaborate than that of his later film work, but even in miniatures like "Jeff" you can see evidence of the care he took in framing, his attentiveness to mood, and his already highly sophisticated sense of film rhythm. Some of those qualities were apparent, too, in his first feature, The Deadly Companions (1962), a traditional Western that was, unfortunately, saddled with a mediocre script and the first in what would be a long line of producers who were, let's say, not wholly in tune with the director's unique and defiantly ornery sensibility.

He fared a lot better with his second picture, Ride the High Country (1963), an elegiac tale of two aging westerners, played by Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott, hired to transport gold from a mining camp to a bank in town. Both are ex-lawmen (and old friends), but their attitudes toward the task at hand are very different. Scott is plotting to steal the gold, while McCrea just wants to do the job well and get paid, and his response to his partner's efforts to tempt him is eloquent: "All I want is to enter my house justified." The movie, like most good Westerns and every Sam Peckinpah film, of whatever genre, is a morality play. Its style, as in the best Westerner episodes, is classical and rather contemplative, so when violence erupts there's weight to it. But not always the same weight. An ugly incident in the mining camp is played for shock; the final showdown, in the yard of an isolated farm, has a melancholy quality, an aura of sad necessity, and it features a slow walk that's nearly the equal of the one in The Wild Bunch. In the last shot the hero, dying, sinks out of the frame.

On the strength of Ride the High Country, which was well-reviewed and, despite poor distribution, did decent business, Peckinpah was hired for a much bigger project, a cavalry epic called Major Dundee (1965), with major stars (Charlton Heston, Richard Harris) and a strong supporting cast (James Coburn, Jim Hutton, Warren Oates). He seems to have determined that on this larger canvas he could paint a masterpiece—something like John Ford's Fort Apache, only better—and in pursuit of greatness ran over budget, behind schedule, and fought so bitterly with the producer that he nearly got himself fired. With Heston's intervention, he was allowed to finish, but the studio release was heavily cut. The action sequences, on a much larger scale than those of Ride the High Country, are well staged—using multiple cameras, as he would for the rest of his career—but they weren't all he'd had in mind; he'd wanted to mix some slow-motion shots into the montage. That idea would have to wait.

It wound up waiting four years. His pitched battles with the higher-ups on Major Dundee damaged his reputation, and on his next assignment, a Steve McQueen vehicle about poker players, The Cincinnati Kid, he was relieved of his directorial duties after just four days of shooting. (Norman Jewison completed the film.) At this point Peckinpah, now virtually unemployable in the movie industry, turned back to television and got lucky. He was hired to direct an adaptation of the Katherine Anne Porter novella Noon Wine for the anthology series ABC Stage 67, and it was ideal material for him: an odd, ambiguous story about a Western farmer (Jason Robards) who one day kills a man for reasons he can't fully explain to his family, his neighbors, or even, finally, to himself. With a seven-day shooting schedule, using mostly videotape, Peckinpah brought out every nuance of a tale in which, as is often the case in his best work, practically everything of importance is unspoken. Noon Wine doesn't look much like his movies, or the television shows he shot on film, because his videotape editing style is different: Instead of intricate crosscutting, he relies more heavily here on dissolves and superimpositions. But the effect is comparable: Every scene is packed, dense with visual and emotional information.

Noon Wine, which earned a DGA Award nomination, got him back in the game, and in The Wild Bunch he seemed determined to risk all his artistic capital on a sweeping vision of the Western experience as he understood it. He put everything on the table, as if he had nothing to lose, and made the sort of film he had hoped Major Dundee would be. Anger isn't always a useful creative force, but Peckinpah's feelings about the Dundee fiasco and the four years of relative inactivity that resulted from it must have deepened his empathy with the aging bad men of The Wild Bunch, who feel hemmed in by the West of 1914, unable to live as they've always lived, betrayed by history: Their rage, and his, is never far from the surface in this picture, and when it is at last fully vented in that spectacular, suicidal battle at the end, the effect is awe-inspiring, tragic, like Lear railing at the wind. If you're living in a disintegrating world—or working in a slowly dying genre—you might as well go out with a bang.

The Wild Bunch earned Peckinpah another DGA Award nomination, and made him famous, though not entirely in a good way: Glib journalists started calling him "Bloody Sam." And although he'd been allowed to make the film the way he'd wanted to, that wasn't the film most American audiences actually saw in 1969: After a few weeks in release, the studio hacked 10 minutes out of it, because theater owners wanted to squeeze in extra showings. (The full 145-minute version was shown in Europe, and was restored for rerelease in the United States in 1995.) Another grievance in a lengthening list.

During the next decade, Peckinpah worked steadily, and often well—until booze, drugs, and, especially, paranoia got the better of him. If his career had had the shape of a conventional Hollywood narrative, it would have ended with the triumph of The Wild Bunch; if there were any justice in film history, it would have been the last Western ever made. But life isn't like that, and neither are Peckinpah's movies. The Old West took awhile to disappear; so did he. He made nine pictures in the next nine years, of which a couple, both set in the West, are leisurely, graceful, wistfully comic, and almost entirely free of violence. The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), is a tall tale of the Old West, whose title character (Jason Robards) finds water in the desert after being left for dead by his snaky partners, and then, a second miracle, finds love with a beautiful prostitute (Stella Stevens). It's his most playful film: He indulges himself with a musical sequence, a few scenes of speeded-up motion, and even a brief, goofy bit of animation. Junior Bonner (1972), set in the contemporary West, is a gently funny family drama about a beat-up rodeo cowboy (Steve McQueen) and his estranged parents (Robert Preston and Ida Lupino). Both of these lovely movies are, in essence, affectionate tributes to the sheer cussedness of westerners, and both were promoted and distributed so indifferently that almost no one saw them.

But most of Peckinpah's post-Wild Bunch work is dark, bitter, and conflicted. Straw Dogs (1971), set in the English countryside, shocked audiences even more than The Wild Bunch had, because there's sexual violence, too—a vivid, interminable-seeming rape scene in which the victim's feelings about what's happening to her shift disturbingly from moment to moment, alternating between fear and involuntary pleasure. (The scene, as Susan George plays it, is as emotionally complex as any of the fraught couplings in Last Tango in Paris.) Straw Dogs, intimate, simmering, claustrophobic, may be Peckinpah's most technically brilliant film. The bloodshed in its climactic sequence is far more intimate than that of The Wild Bunch's concluding massacre: The dimmer, tighter spaces here generate a different kind of horror. And Peckinpah's editing is bold even by his own standards: During the rape, he cuts in shots of the victim's husband (Dustin Hoffman), alone in a field, for spatial contrast; in a later scene, at a village dance, he interrupts a close-up of George with fast, near-subliminal flashbacks to the outrage—little stabs of memory, drawing blood every time.

Peckinpah would use that technique frequently in his subsequent films, to show how the past keeps breaking into the present. He seemed to know how it felt. The stories he tells about the modern world—The Getaway (1972), Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), The Killer Elite (1975), and The Osterman Weekend (1983)—are almost exclusively about betrayal; so is his fierce World War II drama Cross of Iron (1977). The air is thick with grudge. As Peckinpah's art was clouding over, his influence was, perversely, spreading. In the '70s and '80s, directors like Walter Hill (who wrote the screenplay for The Getaway), Kathryn Bigelow, and, in far-off Hong Kong, John Woo began to adapt his enveloping, immersive editing style to their own purposes, and action in the movies generally became more, well, exciting. Peckinpah had raised our expectations, even as, in the last decade of his life, his own seemed gradually to dim.

He was a great, innovative craftsman of film, but his sensibility was unique, inimitable. Action filmmakers can use an impersonal, impeccably directed movie like The Getaway as a textbook. But whatever it was that possessed Peckinpah on the morning he dreamed up The Wild Bunch's majestic walk is fundamentally unteachable. And it's probably safe to say that no one will ever again make—or feel the impulse to attempt—a movie like his last Western, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). In telling the well-known story of the lawman Garrett's pursuit of his old friend Billy, Peckinpah slows the narrative to a fatalistic mosey—sleepwalk set to the tempo of faintly jingling spurs. The movie is, in its way, as daring as The Wild Bunch: There's a lot of dying here, but in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, the deaths come one at a time, with mournful regularity. It's the only one of Peckinpah's films in which the director himself appears on screen: He plays a coffin maker.

The studio mutilated that one, too, and Peckinpah rode out of town before doing a final edit. On the most recent special edition DVD, there are two non-definitive versions, one a preview cut and the other a fine cut assembled from the original studio release and the existing preview. The film, in either version, is beautiful and spooky. It dramatizes, and embodies, the slow dying of the West so thoroughly that it feels posthumous. Sam Peckinpah lived nearly a decade longer: He died of heart failure in 1984, a few months shy of his 60th birthday. It's impossible to know if he felt that he was entering his house justified. But as a film artist, he walked the walk, and it was a westerner's walk.