Untitled Document

BY CHRISTINE CHAMPAGNE

If there is one place a commercial director wants to be on Super Bowl Sunday, it’s in the game. After all, the Super Bowl is the premier showcase for commercials with a staggering number of Americans watching the National Football League’s championship showdown. Last year’s Super Bowl XLV drew an estimated 111 million viewers, making it the most-watched television program ever. And this audience doesn’t fast-forward through the commercials. The spots are as highly anticipated as the game itself. A poll of young adults conducted days before last year’s game revealed that 59 percent were actually looking forward to seeing the advertisements.

“When I got into advertising 20 years ago, I became acutely aware that if you were going to have your spots play on a national stage and have people talk about them, the Super Bowl was the place to be,” says director Samuel Bayer, who was behind Chrysler’s heralded “Born of Fire,” an emotional two-minute tribute to Detroit featuring Eminem that aired during last year’s Super Bowl and won the 2011 Emmy Award for Outstanding Commercial.

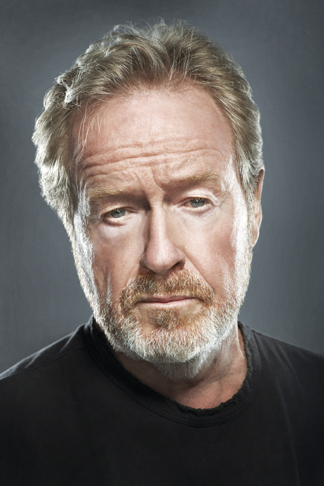

The Super Bowl, first played in 1967, wasn’t always such a major platform for commercial directors. Some memorable work had emerged from the early years, including the legendary 1980 Coke “Mean Joe Greene” commercial directed by Lee Lacy that had the football star famously tossing his jersey to a young boy who gave him a Coke. But it was Apple’s “1984,” directed by Ridley Scott, that blew the game wide open in terms of how epic and powerful a Super Bowl commercial could be. “What I received was the script, and because I wasn’t computer savvy—I’m a pen and paper man still—I didn’t know Apple or what it was,” says Scott. “What attracted me [to the job] was the absence of the product in the narrative and no mention of what it was or what it could do. Brilliant!”

The late Steve Jobs, whom the director never met, had expressed concern about not seeing the product being advertised the Macintosh computer in the commercial, according to Scott’s recollection. But the agency stood behind the idea, Scott says, adding, “The rest was history. It certainly converted Steve to advertising.”

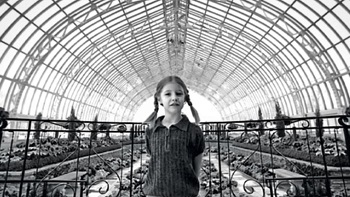

The spot, which aired in 1984, opens with a startling image of a woman sprinting down a dark corridor clutching a hammer and being chased by police. The woman ultimately bursts into a chamber full of zombie-like men dressed in drab gray paying rapt attention to a Big Brother-like figure spewing propaganda projected onto a giant screen. The leader’s spell is broken when the heroine hurls her hammer at the screen, causing it to explode and signaling the arrival of a new era in computing.

Not to mention a new era in commercial directing. Scott had been directing commercials and films; he already had Blade Runner under his belt for nearly 20 years when Chiat/Day approached him to direct “1984.” After it aired, everyone wanted to know who directed it. “Producers were slowly realizing that the guys from TV commercials were capable of making movies,” says Scott. “So they hunted down who made the Super Bowl spot only to discover [in this case] it was an old hand.”

While high-profile Super Bowl work can elevate a commercial director’s career within the advertising industry and beyond to this day, the opportunity to quarterback a spot broadcast during what is a critical advertising showcase comes with high expectations and demands. Clients are shelling out anywhere between $250,000 to a couple of million dollars on production costs, and millions more on the airtime buy, which averaged $3 million for 30 seconds last year. Chrysler spent $9 million to buy two minutes for “Born of Fire.”

Directors start bidding on Super Bowl spot jobs based on briefs from advertising agencies beginning in the summer prior to the game. That process heats up in the fall, and the competition is fierce. “The bidding process is also part of the conceptual process of a job,” says Lance Acord, who directed Volkswagen’s “The Force” spot for last year’s Super Bowl. “The agency is engaging with directors to get their input and take on a script, then in a collaborative way develop and evolve the idea.”

That said, an idea is never set in stone. It’s not uncommon for concepts to be drastically altered, or even scrapped and replaced with new ones right before a spot is set to be shot. Just ask director Bryan Buckley. He made his Super Bowl directing debut during the 1999 game with Monster.com’s “When I Grow Up,” a funny but sobering spot in which children talk about their career aspirations, which includes filing all day and clawing their way up to middle management. It was a great concept, but it wasn’t the assignment Buckley was initially awarded. “There was an entirely different board when I won the job somebody sitting in a shrink chair, talking to a psychiatrist about getting a better job. They switched it to “When I Grow Up” at the last second,” says Buckley, who had to quickly shift gears to shoot a commercial that was entirely different in terms of look and tone from what he had initially prepared for. In the end, the spot helped him win the DGA Award for Outstanding Achievement in Commercials that year.

But that wasn’t the only kudos Buckley received at the DGA Awards that night. Steven Spielberg came up to him and told him how much he liked the spot, and recalled him asking, “Did you shoot it black and white, or did you drain the color?’ I said, ‘I shot it in black and white,’ and he said, ‘I knew it!’ It was a great moment. It was so surreal that he was thinking about that.”

There are also the instances not uncommon when the addition of a famous face to a Super Bowl spot means a director has to scramble to make enormous changes at the last minute. Buckley was working on last year’s Best Buy futuristic shopping spoof “Ozzy vs. Bieber,” starring Ozzy and Sharon Osbourne and Justin Bieber, right up until the eleventh hour because Bieber only became available for the shoot at the last minute. And last year Bayer had to hop on a plane from Los Angeles back to Detroit to shoot additional scenes for “Born of Fire” only 10 days before the Super Bowl after Chrysler signed a deal with Eminem for him to appear in the spot.

Super Bowl spots generally don’t go into production until December or even January, just weeks before the game, and if there is one element of preproduction that directors focus on most intensely, it’s casting. “It all comes down to casting,” says Acord, who saw countless kids maybe hundreds, he says when he was looking for a young boy to star in “The Force,” which centers on a kid who is dressed up like Darth Vader and attempts to employ the Force to move household objects.

Acord had a much easier time with a 5 year old than Joe Pytka had with Michael Jordan, who famously showed up two hours late for the Nike “Nothin’ But Net” shoot that had him playing an increasingly complicated game of hoops with Larry Bird. A snag in contract negotiations kept Jordan from reporting to the shoot on time, and that presented a big problem for Pytka, who had only been allotted six hours to shoot the spot with the two basketball stars. “When he finally got there, I asked him if he was going to give me the two hours,” says Pytka. “And he said, ‘No.’ ” So Pytka had to move fast to capture all the action in just four hours. He succeeded, and the spot, which ran during 1993’s Super Bowl XXVII, remains popular to this day.

While Pytka had to get the Nike spot done in just a few hours, the average Super Bowl commercial shoot is one full day two for more complex productions. “The pressures are always immense, especially going into the shoot days, but it’s like a sport, and, personally, I have a tendency to like the rush of that chaos and nervousness,” says Buckley, who has been a regular contributor of commercials to the Super Bowl sometimes five per game for more than a decade. “You have to be ready for the ride and say, ‘Okay, this is going to work out.’ ”

Directors who go against the grain when it comes to production have done some of the most successful Super Bowl work in the last decade. While the Super Bowl is generally known for slick, colorful commercials, Craig Gillespie chose to go another route when he shot the Ameriquest spot “Surprise Dinner,” one of the commercials that landed him the 2005 DGA Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Commercial Directing. “I wasn’t shooting it like I was shooting it for the Super Bowl. We went against all notions of Super Bowl production value,” says Gillespie, who shot handheld, creating a grainy, dark look for the spot about a guy preparing a surprise dinner for his girlfriend, only to have the cat knock over a pot of tomato sauce.

It didn’t look good for the guy when his girlfriend entered the apartment and saw him standing in the kitchen holding a knife in one hand and a sauce-covered cat in the other. As the spot was originally storyboarded, the cat knocked over the pot of tomato sauce while it sat on the counter. Gillespie had an idea to make the spot even more dramatic by putting the pot on the stove so when it fell it looked like a shocking pool of blood. But he only had three takes to get it right.

“It was really up to me to set up the joke in the most surprising way,” says Gillespie. “And by shooting it the way I did, not making it feel like a comedy spot you’d expect to see on the Super Bowl, the payoff was all that much more surprising.”

Buckley had also taken an unusual approach by shooting “When I Grow Up” in black and white. “The idea was to do something to counter what was out there and to make it prettier,” says Buckley. “I do remember the client asking, ‘Why do we have to shoot this on film?’ He was sort of ahead of his time, I guess."

Shooting digitally is certainly more common now. More and more directors, including Pytka, are going digital for the big game and beyond these days. “Film is not a luxury anymore. Film is archaic,” says Pytka, who mostly shoots with the Canon 7D. “I hate to say it because I was a film guy from the beginning, but in the last two or three years digital technologies have improved so much that it’s made film somewhat obsolete.”

Acord, a director and cameraman who has been a DP on feature films ranging from Lost in Translation to Being John Malkovich, shoots all of his own commercial work. He shot “The Force” with Arri’s Alexa digital camera. “I’d done some testing with it, and I knew it would work beautifully for the final shot of the car at the end, and working with a kid and being able to turn the camera on and let it roll and roll and roll was great,” says Acord. “I love shooting film. It’s still my favorite format to work with, but I also love to experiment.”

Bayer, also a director and cameraman, shot “Born of Fire” himself, although he passed on digital in favor of shooting on 35 mm film because he wanted to achieve a gritty look. “It was guerrilla filmmaking in Detroit,” says Bayer, who captured moving shots from a van. “There was no Technocrane, no Steadicam, no lights.”

Bayer isn’t sure if he wants to direct another Super Bowl spot after the success of “Born of Fire.” “I think I am going to leave on top,” he says half-seriously. “Historically, the stuff I have done for the Super Bowl was right at the bottom of the list. It was always very depressing. I’m just so excited that I had a good one, and people remember it, and I can bring it up at cocktail parties.”

While Scott’s “1984” elevated Super Bowl spot-making to a new level, it was Pytka who took the ball and ran with it. This prolific director, who has won the DGA Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Commercial Directing three times and earned a record 15 nominations, made his mark with a string of hits that rolled out game after game starting in the early 1990s, including the rousing Ray Charles Diet Pepsi “You’ve Got the Right One Baby, Uh-Huh” commercial; the Nike “Hare Jordan” spot that had Bugs Bunny bouncing around a basketball court with Michael Jordan; and all of those Budweiser Clydesdale ads that in Pytka’s hands became an honored game-day tradition for Anheuser-Busch.

Pytka is not shy about saying he longs for the good old days when he first got into the game and directors had the final word as to how a Super Bowl spot was made. It’s not like that these days, he maintains. “The process is so complicated in ‘Panicsville,’ which is the state of the industry now,” says Pytka. “Instinct used to run the business, but now with everyone being a corporate conglomerate, it’s all down to research.”

To wit: Pytka recalls longtime client Anheuser-Busch, which was acquired by InBev a few years ago, getting focus group feedback for the storyboards for a spot titled “Clydesdale Fence,” which chronicles the friendship between a Clydesdale colt and a calf, before it was shot. When it came time for Pytka to direct the spot, the director says he wasn’t allowed to deviate from the research-approved storyboards, so he wasn’t able to add key scenes he thought necessary, and the spot didn’t make the cut for the Super Bowl or so it seemed. Pytka later went back into production and shot additional scenes for the commercial at his own expense, which is unheard of, and “Clydesdale Fence” came together in the editing room and not only aired during Super Bowl XLIV, it was one of the 2010 game’s most-acclaimed spots. Pytka says he felt vindicated by the end result.

So what makes a successful Super Bowl commercial? While there isn’t necessarily a winning formula, there is no denying that humor helps. And if you can throw in some cute babies or animals even reptiles, judging by the enduring popularity of the 1995 Budweiser “Frogs” spot directed by Gore Verbinski into the Super Bowl spot mix, well, it can’t hurt.

Gillespie has often relied on deftly employed visual gags. “Visual storytelling works well during the Super Bowl because there are so many places where people are watching the game where it’s loud,” he says. “If you see something that you can actually watch without hearing the sound, and it still tells the story, that helps.”

While the Ameriquest “Surprise Dinner” commercial is a brilliant example of this, Gillespie also had a hit with the 2010 Snickers ad “Game,” which featured a young guy playing football with his friends. Hunger strikes and he turns into a cranky old lady in the form of Betty White, who then gets tackled. Like “Surprise Dinner,” Gillespie also shot “Game” handheld, but the spot was heavy on effects because of the tackle. “It looks like we really did tackle Betty White, and that’s the fun of it,” says Gillespie. “But it’s the work of a good effects company. We shot it twice—once with Betty and the stunt guy running in toward her and making contact but not knocking her down, and then we did the same exact move with the stunt guy tackling a stunt person. The effects people combined the two, and they even took Betty’s face and placed it on the stunt person who got tackled.”

As well as humor works, Super Bowl spots aren’t solely about laughs, especially these days. Since 9/11 more serious and emotional commercials have taken center stage during the game, including 2005’s “Applause,” directed by Pytka for Anheuser-Busch. In the spot service people are shown returning from war, walking through an airport where they were greeted with spontaneous applause. Pytka would only direct “Applause” if two conditions were met there was to be no product in the commercial and real soldiers were to be cast. The client acquiesced on both. “This is about as altruistic as you could get in a commercial,” says Pytka. “I have always felt that the best commercial doesn’t need to have any logos in it.”

Pytka cast the service people featured in the spot from photos and only met them the day of the shoot. Not ideal, but dealing with the military to get permission was a complicated process, according to the director, who shot the commercial at Los Angeles International Airport. “I’ve shot at LAX many times over the years, and I have a good relationship with those people. There’s a food court above the check-in counters [in one terminal], and they were able to close it off, and we built a gate,” says Pytka. “We kept the colors on the set muted to keep the focus on the service people.”

Pytka didn’t spend a lot of money to shoot “Applause,” which is often the case in today’s economy, but the perception is that some of the most celebrated Super Bowl commercials had exorbitant budgets.

Scott recoils when asked if it were true that he had $900,000 to make “1984.” “Bollocks! It was approximately $250,000. People say this, and it is really irritating. The million dollars was spent on the air buy time, not on the spot,” says Scott. “Actually, I got a lot of work [back then] because I was so competitive with budgets,” Scott adds. “I’d go for an idea always, never because there was a big budget.”

For many of the top commercial directors working today, it all comes down to the idea. If they fall in love with the concept, it’s not always about how big or expensive the spot is. “It’s a pretty critical audience watching the Super Bowl now,” says Acord. “The little Doritos ad that cost $120 grand to produce can sometimes have way more impact than the $2 million ad that’s just a lot of eye candy.