By F.X. Feeney

Photographed by Scott Council

Chicago born and raised, Michael Mann was majoring in English literature at the University of Wisconsin when a screening of G.W. Pabst's The Joyless Street moved him to want to become a director. Discovering Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove at a local theater later that same year closed the deal. He entered the London Film School in 1965, then crossed to Paris as a film correspondent for NBC television to cover the May 1968 student uprisings. He returned to the U.S. in 1971 and made his first mark in television, writing for Starsky and Hutch and directing Police Woman and a number of movies for television, culminating in The Jericho Mile (1979), which won a DGA Award and was released to critical acclaim as a theatrical feature in Europe.

Chicago born and raised, Michael Mann was majoring in English literature at the University of Wisconsin when a screening of G.W. Pabst's The Joyless Street moved him to want to become a director. Discovering Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove at a local theater later that same year closed the deal. He entered the London Film School in 1965, then crossed to Paris as a film correspondent for NBC television to cover the May 1968 student uprisings. He returned to the U.S. in 1971 and made his first mark in television, writing for Starsky and Hutch and directing Police Woman and a number of movies for television, culminating in The Jericho Mile (1979), which won a DGA Award and was released to critical acclaim as a theatrical feature in Europe.

While learning the ropes, Mann was saving his money and building his own production company.

His successful TV work in the 1980s—Miami Vice and Crime Story—afforded him the autonomy to choose only those projects that most excited him. Asked recently how he was able to maintain creative control over his first theatrical feature, Thief (1981), he replied: "Easy. I cut the checks."

In all, he has directed 10 features, creating a body of work that is abundantly energetic in its precision and variety, from the psychologically layered crime film Heat (1995), to the historical epics The Last of the Mohicans (1992) and Public Enemies (2009), to an all-American study of corruption, The Insider (1999).

Most recently, Mann directed the pilot and is the executive producer of the new HBO horse racing series Luck. We caught up with him at his Santa Monica-based production company, in his office filled with skyscrapers of books and art and artifacts from the many eras he's visited in his movies.

F.X. FEENEY: A lot of directors know from an early age that this is what they want to do. Did you have a life plan that you wanted to make films?

MICHAEL MANN: I wasn't really interested in cinema until I saw Dr. Strangelove, alongside a set of films by F.W. Murnau and G.W. Pabst for a college course. These were a revelation. I'd already seen some of the French New Wave and some Russian films, but the idea of directing, of shooting a film myself? Never. Prior to Strangelove, it simply had not seemed possible that you could work in the mainstream film industry and make very ambitious films for a big mainstream audience. The whole film is a third act. The mad general played by Sterling Hayden is totally submerged in his character the moment we first encounter him. There's no prelude, no context. We're just with him, we know who the guy is, and we catch up along the way. Even as a young man I found that intensity very exciting—how immediate it was.

Q: So how did you organize yourself as a director? What did you have to pull together to make it happen?

A: One of the most instructive events was when, right out of the London Film School, I got a job working for Bill Kaplan in the British office of 20th Century Fox in Soho Square. Bill was production supervisor for a lot of films that were being made at that time in England, owing to the budgetary rebates then in force under The Eady Plan. Working in physical production, helping organize scheduling, budgeting, and production logistics became for me a model of how to think, of how to organize the totality of a movie. I apply the lessons I learned there to this day, not just in terms of budgeting—but in terms of the content of a movie. There's a critical planning that is very three dimensional at this early stage. That has become really important in everything I've done since.

Q: Your earliest films were documentaries. Is that what formed your commitment to authenticity?

A: My ambition was always to make dramatic films. I had a strong sense of the value of drama growing up in Chicago, which has long had a thriving theater scene. I'd also found, working a lot of odd jobs as a kid—as a short-order cook, on construction, or as a cab driver—that there was tremendous richness in real-life experience, and contact with people and circumstances that were sometimes extreme. I was drawn to this instinctively. You find out things when you're with a real-life thief, things you could never make up just sitting in a room. The converse is also true: Just because you discover something interesting, you don't have to use it; there's no obligation. Yet life itself is the proper resource. I've never really changed that habit of wanting to bring preparation into the real world of the picture, with a character that actors are going to portray.

Q: Is that why you develop biographies for every character, not just for your use but for your actors as well?

A: I like to know everything about a character. Major characters, minor characters, even if a picture's got nothing to do with what their childhood is, I want to know what their childhood was like. What were their parents like? Where did they grow up? What do they like, what do they not like? What kinds of women are attracted to them? Why are these women attracted to them? If the character is a woman, who is she? How is she relating to the situation of her life?

Q: In a period piece such as The Last of the Mohicans, it must have been difficult to get the kind of authenticity you're after.

A: Making The Last of the Mohicans was particularly challenging. We were trying to re-create the conditions, the tones, the value systems of 1757, particularly for somebody raised in an Algonquian-speaking tribal group, such as the Mohicans. How does Hawkeye come on to a woman? How does he say, 'Hey: I like you. Let's go out?' Behind that is an anthropological perspective I always want to have. I want the actor to have that same deep clarity about his or her character. Mind you, this inquiry includes not wasting time on stuff that is immaterial. On The Insider Russell Crowe met the real Jeffrey Wigand three times, and then we both said, 'That's enough.' He got everything he needed, and there was that fine point in which he was still on a frontier—needing to project and extrapolate what Jeffrey would do. The trap both Russell and I wanted to avoid was falling into a Xerox of the actual guy. I didn't want anything imitative. What results therefore is Russell's evocation of Wigand, the essential, authentic Wigand that's based on his origins and what he's confronting.

MAKING IT REAL: Mann, directing Daniel Day-Lewis (right), tried to

MAKING IT REAL: Mann, directing Daniel Day-Lewis (right), tried to

re-create conditions of 1757 for The Last of the Mohicans.

Q:What was your connection to Wigand as a character in this drama?

A: The beauty of Wigand is his awkwardness. He was definitely a hero, warts and all. He's a scientist who went to work for a tobacco company—for the money. That's what makes his obstinacy so heroic. His personal failings by contrast are what make him so much like us. If there had been bonding and pal-ship between him and Lowell Bergman [the producer from 60 Minutes goading him to take action played by Al Pacino], I might not have had the idea to make the film. It was precisely because Lowell didn't exactly care for the guy, and yet put everything on the line to defend him, that I could access him, access the pair of them, and hopefully persuade the audience to access him.

Q: Are you conscious of choosing actors who share your intensity?

A: It's usually a good idea. [Laughs] I've made one or two mistakes, but most of the people I've worked with are really down for the cause.

Q: Do you like to rehearse your actors before and during shooting?

A: Yes, but never for too long. There's an art to rehearsal. Never rehearse to the point where you wish you'd shot it. I always want to stop just before the moment becomes so actual that I wish I had a camera. I don't want that to happen until take 3 or 4 of the day we're shooting it. You always want to back off, you always want to leave potential. There's a tremendous thrill for me in finding the spontaneous moment. Sometimes that happens when you're smart enough not to rehearse too much—when you know where to stop, because otherwise you'll get too programmed. Other times, that spontaneity comes with a liberation you get at the end of tremendous preparation—where everybody is confident and the players know exactly what they're going to do.

Q: How did you apply that to the famous coffee shop scene between Al Pacino and Robert De Niro in Heat (1995) when the two adversaries meet head-to-head for the first and only time?

A: We did two things: We discussed the scene. Then we did some rehearsals, but I was wary because the entire movie is a dialectic that works backward from its last moment, which is the death of the thief Neil McCauley [De Niro], while the detective Vincent Hanna [Pacino], who's just taken McCauley's life, stands with him as he passes. The 'marriage' of the two of them in this contrapuntal story is the coffee shop scene.

Now Pacino and De Niro are two of the greatest actors on the planet, so I knew they would be completely alive to each other—each one reacting off the other's slightest gesture, the slightest shift of weight. If De Niro's right foot sitting in that chair slid backward by so much as an inch, or his right shoulder dropped by just a little bit, I knew Al would be reading that. They'd be scanning each other, like an MRI. Both men recognize that their next encounter will mean certain death for one of them. Gaining an edge is why they've chosen to meet. So we read the scene a number of times before shooting—not a lot—just looking at it on the page. I didn't want it memorized. My goal was to get them past the unfamiliarity of it. But of course these two already knew it impeccably.

WHISTLE-BLOWER: Mann, working with Al Pacino and Russell Crowe on The Insider, was

WHISTLE-BLOWER: Mann, working with Al Pacino and Russell Crowe on The Insider, was

intrigued that these two characters didn’t like each other but were entwined in their fight against big tobacco.

Q: You made an interesting choice directorially in the finished film. The whole scene takes place in over-the-shoulder close-ups—each man's point of view on the other.

A: We shot that scene with three cameras, two over-the-shoulders and one profile shot, but I found when editing that every time we cut to the profile, the scene lost its one-on-one intensity. I'll often work with multiple cameras, if they're needed. In this case, I knew ahead of time that Pacino and De Niro were so highly attuned to each other that each take would have its own organic unity. Whatever one said, and the specific way he'd say it, would spark a specific reaction in the other. I needed to shoot in such a way that I could use the same take from both angles. What's in the finished film is almost all of take 11—because that has an entirely different integrity and tonality from takes 10, or 9, or 8. All of this begins and ends with scene analysis. It doesn't matter if it's two people in a room or two opposing forces taking over a street. Action comes from drama, and drama is conflict: What's the conflict?

Q: At the opposite end of the scale from that intimate two-man scene in the coffee shop is the huge street-battle in Heat. How did you prepare a sequence that massive?

A: That scene arose out of choreography, and was absolutely no different than staging a dance. We rehearsed in detail by taking over three target ranges belonging to the L.A. County Sheriff's Department. We built a true-scale mock-up of the actual location we were using along 5th Street in downtown L.A., with flats and barriers standing in for where every parked car was going to be, every mailbox, every spot where De Niro, Tom Sizemore, and Val Kilmer were going to seek cover as they moved from station to station. Every player was trained with weapons the way somebody in the military would be brought up, across many days, with very rigid rules of safety, to the point where the safe and prodigious handling of those weapons became reflexive. Then, as a culmination, we blocked out the action with the actors shooting live rounds at fixed targets as they moved along in these rehearsals. The confidence that grew out of such intensive preparations—all proceeding from a very basic dramatic point—meant that when we were finally filming on 5th Street, firing blanks, each man was as fully and as exactly skilled as the character he represented.

Q: What was the 'conflict' your choreography was proceeding from?

A: McCauley's unit wants to get out, while the police want something else, and are sending in their assets. Judged strictly in terms of scene analysis and character motivation, the police are used to entering a situation with overwhelming power on their side. When they're assaulted by people who know what they're doing, they don't do well. McCauley's guys are simply more motivated, and have skills that easily overwhelm the police. Choreography has to tell a story; there's no such thing as a stand-alone shootout. Who your characters are as characters determines your outcome.

Q: Collateral (2004) is largely a two-character drama, which must have created its own demands. How did you prep your players for that film?

A: Prepping Jamie Foxx for his role in Collateral was a matter of getting him to understand the neighborhood this man came from, and the death-by-repetition involved in being a cab driver. Having been a cab driver myself, I knew what a grind that is. For Tom Cruise, who plays a hit man, the preparation involved all kinds of crazy stuff in preproduction—acquiring the skill sets he would need to be this man. We had him stalking various members of the crew for weeks, in secret, learning their habits, and then picking the moment. This person would be coming out of a gym at 7 a.m. and feel somebody slap something on his back—and it would be Tom, who had just put a Post-it on their back. In our virtual world, that was a confirmed kill.

Q: Each of your films seems to set out in a different direction from the one that preceded it. What attracts you to a project?

A: Usually I think I know what I'm going to look for next, and usually that turns out to be wrong. How I chose to do Collateral is a prime example. I had just come off of doing Ali (2001), a picture about a huge real-life figure. I had developed The Aviator, about Howard Hughes. But as brilliant as John Logan's screenplay was, and as much as I wanted to work with Leonardo [DiCaprio], I felt I would be doing a rerun of what I'd just done. What attracted me to Collateral was the opportunity to do the exact opposite: a microcosm; 12 hours; one night; no wardrobe changes; two people; small lives; inside a cab; a small time frame viewed large. I very much admired the hard, gem-like construction of Stuart Beattie's screenplay. There were a lot of modifications as we prepared to shoot, but the structure was there from the start—and it was tremendously appealing. That made my decision. I asked Marty [Scorsese] if he wanted to do The Aviator.

The idea for The Last of the Mohicans came to me because I'd seen the film written by Philip Dunne when I was 3. I realized 40 years later that it had been rattling around in my brain ever since, that it was a part of me, a very important part. I just hadn't been consciously aware of it up to that point. I also thought: There hasn't really been an exciting epic, period film in a long, long time. Joe Roth and Roger Birnbaum were running 20th Century Fox at the time. They got the excitement of it immediately.

Q: Even though you're always trying to do something new, there seems to be continuity in your work.

A: As far as the continuities you're noticing in my work, those are arrived at film by film, and are not planned as such. The film directors I admire most don't consciously have a form that is their form. Marty Scorsese doesn't say to himself: 'I will make a certain decision this way because it either does or doesn't conform to my form.' No, what he chooses to do flows from him organically. I think that's the case for every filmmaker. The more diverse one film is from the other, the more exciting it is. What you want is to find yourself on a frontier. For the working director, there is no conscious form from film to film. We all know what our ambitions are, but in a very healthy way we are all unconscious of 'signature.'

Q: In Public Enemies you shaped your portrait of John Dillinger to dramatize the fact that a series of revolutions in technology—the speed of cars, telecommunications, even the power of movies—had made his career possible.

A: Our digital age is older for us than was Dillinger's access to high-speed travel. He could pull off major robberies in a single 10-day period, starting in Minnesota, jumping to Indiana, then speeding to Tucson to take a break. His ability to do that was less than five years old. One irony that attracted me was, here was a guy who did formal planning, who had a deeply methodical approach to every single score, yet was on a ride to nowhere specific. He had no outcome goal. There was no plan for his life in the sense that Butch and Sundance had said, 'Once we accumulate X amount of capital, or the risk gets too extreme, let's head for South America.' I don't think the film succeeds in conveying this. That point eluded me. If I were making the film all over again, maybe a whole different screenplay would be written.

Q: Yet this is an abiding theme. Neil McCauley in Heat is in a similar position—ready to walk away from any life situation on a moment's notice.

A: I'm attracted to characters who are conscious of trying to figure out what they're doing here, and what's the best way to do it. Maybe that's because I'm engaged in the same thing and I either have, or I haven't!

DRIVE, HE SAID: John Dillinger’s access to high-speed transportation made his kind

DRIVE, HE SAID: John Dillinger’s access to high-speed transportation made his kind

of multi-state bank robbery spree possible for the first time in Public Enemies.

Q: Music is an important element in all your work. Do you use it to pre-imagine your films, or are your choices discoveries you make in postproduction?

A: As research, music enters early for me. If you can find that piece of music which evokes the central emotion of one of your characters, some pivotal crisis where he or she must rouse themselves from despair and manifest something very aggressive within his or her own mind—this becomes the piece of music for that moment. If I want to quantify how a character is feeling and thinking, in a way that is replicable, so I can re-evoke that emotion many, many times, finding the right piece of music is positively essential. Not only as I prepare the scene—but as I shoot the scene, as I direct the actors, and finally, as I edit the scene. One specific example comes to mind in Collateral, when the coyotes cross in front of the cab. For me, that was a watershed in the story's progression. Each of the two principle characters is submerging into his own perspective of what life is: a retrospective moment; a prelude to a violent confrontation. The song "Shadow on the Sun" by Audioslave nailed that moment for me. It became an indelible part of planning, sustaining, and executing that scene.

Q: You once told me that for Thief, in your mind you saw the city as a 'three-dimensional machine.' Was that behind your choice of the electronic Tangerine Dream score, over the earthy blues you originally considered?

A: One of my great weaknesses is that I'm still hung up on the choice I made over that score. Thirty years later I'm still debating this. By string theory, in some alternate reality, there's a version of Thief with wall-to-wall blues.

Q: Parallel universes aside, you've certainly revisited and re-edited your films on DVD.

A: Highly recommended! I'm all for that.

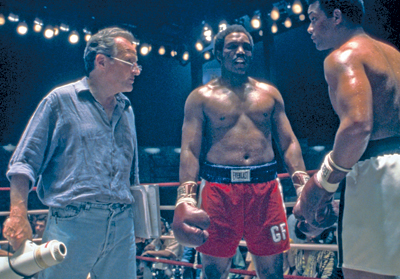

Mann tackled a larger-than-life figure in Ali.

Mann tackled a larger-than-life figure in Ali.

Q: Sometimes you'll match an image entirely to music, but you also use sound effects melodically and integrate audio textures.

A: You have no idea, it can actually get quite nuts. In Thief there's a fire extinguisher going off in F minor. We actually found a way, in Tangerine Dream's studio, of processing actual sound effects and rendering them into a key. This was long before digital computers. The layering can be extraordinarily intricate. During the safe-cracking sequence in Thief, the chaotic sound of the burning bar suddenly stops, and in the silence—corresponding to the bright points of light on the diamonds when the first tray is pulled out—you start hearing a high-pitched note in the key of E, and every once in awhile there's a blast in F minor of the fire extinguisher putting out the embers. This moment happens to work for me, now, in a way that I can still look at and not cringe. It's withstood the test of time. Other things in the film are nonsensical: ocean waves crashing in G minor—sounding big, but yielding nothing at all.

Q: From what I've observed, you keep a very long workday, from the crack of dawn to late at night.

A: In terms of a shooting day? No. I like a 12-hour day, but I'd like to get that down to a 10-hour day. I'm at my best in those kinds of chunks. It all gets down to selection: 'This is really of value.' It's pivotal; if you don't get this particular moment right, you just blew the Act II ending. You go get that thing, and you don't let anything stand in your way. By the same token, there's another event that may show up and be part of the scene that's a visual, and it may be trivial; it really is not important. To be able to have that discretion allows you to direct your concentration and logistical assets to what's really important. The more you can have that discretion of accurately reading: 'This is really pivotal, this really is not,' that is absolutely the key to doing this stuff well.

Q: Does this discretion grow out of the preparatory work?

A: It grows out of the preparatory work, it grows out of experience, and out of necessity. We shot The Jericho Mile under horrendous conditions. We were working in Folsom Prison, and it turned into 19 seven-hour days. Every two hours the guards had to count the population of convicts I had. The IQ of the guards wasn't tremendously high, so if I had 28 convicts out there and three guards are doing a head count, inevitably each one would come up with a different number. 'I got 27.' 'I got 26.' 'I got 29.' [Laughs] Meanwhile we're dying! We were dying in every minute of shooting time.

Q: Over time, you've come to work with the same people again and again. How do you assemble your team?

A: You have to work backward from how great it is when you're in the trenches and who you're there with. If people are as ambitious as you are, you keep them close to you. If a person gets excited by the things I am excited by—say, transforming a run-down arena in the middle of Mozambique that hasn't had electricity or plumbing since 1974, as we had to do for Ali—if a challenge like that gets your blood running, you would be a person I gravitate toward. We would wind up working together on a lot of pictures. My 1st AD Michael Waxman, who is now directing television successfully, has been working with me since 1986. Cinematographer Dante Spinotti and I have done five movies together. There are a number of folks on my crew who've been working with me since Mohicans back in 1991. We're all working now on Luck.

Mann, working with Javier Bardem on a nightclub scene, liked the

Mann, working with Javier Bardem on a nightclub scene, liked the

idea of creating a 12-hour microcosm for Collateral.

Q: As executive producer of Luck, you're in the position of directing other directors.

A: And I want them all to be as expressive as they can possibly be. I directed the pilot. Fidelity to the narrative—the brilliant rotating story tracks devised by David Milch—informs the shooting style, and the disjunctive editing that is so crucial. What most attracted me to David's pilot script is that it doesn't have a beginning, middle, or end. We're suddenly immersed in his characters full form. We encounter each of them in an in instant, without context; then we move to the next character. This is an exciting challenge for any director. Can you bespeak some cloud or challenge in a character's past, purely by conveying their particular attitude to the world around them? Our common ambition became to locate you within these characters as much as possible. That there would be a consistency, a narrative style arising out of these imperatives was a foregone conclusion. All of the directors—among them Phillip Noyce, Mimi Leder, Allen Coulter, Terry George, and Brian Kirk—are bringing their best game. In healthy competitive ways, each wants to do their best work within the series. I do everything I can to encourage that.

Q: Luck has a varied cast with many different kinds of actors. How do you work with someone such as Dustin Hoffman who is a legendary perfectionist?

A: The cast is splendid, I couldn't be happier. But you're wrong to characterize Dustin as a perfectionist. A perfectionist to me is someone who can't tell the difference between detail that's important, and detail that's irrelevant. Dustin concentrates, with great thoroughness, on what's relevant. Something that's not important simply does not arrest his attention. He is so very specific, so grounded in his character that he is never lost. Every look, every action, expresses a determined intention on the part of Ace, the character he's playing.

WIN WIN: Mann appreciates the attention to detail Dustin Hoffman (left) brings to his work on the HBO series Luck.

WIN WIN: Mann appreciates the attention to detail Dustin Hoffman (left) brings to his work on the HBO series Luck.

Q: In terms of creating an aesthetic through the pilot, how do you shoot a horse race?

A: Not by observing, but by conveying the experience of a jockey. I wanted the audience to be, as much as possible, on the horse. There's a lot of lyrical work one can do with long lenses, but I prefer the intimate perspective. As elegant as distance can be, I wanted to take us inside the moment.

Q: So did you mount cameras on the horses as they were racing?

A: No, you can't do that. We tried; it doesn't work. We devised systems for working with small cameras—the Canon 5D or the Canon 1D Mark IV. Then we found various different devices to get us right up next to the horse and drop the camera right in. We built a tracking vehicle. Nothing too advanced: a pickup truck, stripped to suit our purposes, with a hand-operated arm, a lightweight pole a sound man uses, over the shoulder, to lower in these cameras, because they're small enough to do that with. Since then we've made further modifications through practice, failure, and frustration that have enabled us in every episode after the pilot to give us an improved sense of being in among these horses.

There's a whole other aspect of this: getting the horses used to our presence; the question of how many horses we were allowed at a given moment; how frequently we could run them, because of the limitations which we very strictly adhere to for their protection. If we film a race, we can only run them for a third of a mile. Then they get a rest period. We could do that two, maybe three times in a day and that was it. They have a very short day, then they're retired and we use a duplicate set. Sometimes to film a single race we would use three separate sets of horses to get us nine passes.

Q: How many setups do you like to shoot in a day?

A: That depends on the film—but I'd say 30 to 40, on average. Less ever since Collateral, because that was when we began shooting digitally, and did 15-minute takes. But I use two or three cameras quite often. That considerably increases the number of setups. I love working fast. What makes me crazy is waiting; any obstacle to a smooth flow will get me agitated. What you want to be is on a roll. This is what I particularly love about working with Al [Pacino]; we always get into a steady groove. Takes 5, 6, or 7 are generally his golden takes. You get into a tempo with all good actors, a rhythm, and it's wonderful. There's not even verbal communication after awhile. You don't have to talk about it—eyes connect.

Q: What's a Michael Mann set like?

A: Protecting concentration is a big thing for me. I like a quiet set. The actors have the most extraordinarily difficult task: being somebody else, and projecting themselves authentically into a given moment. I'm extremely zealous about guarding their concentration—and mine—from any needless distraction that might interfere.

Q: You've been active in the Guild and a board member for a long time. How has that served you as a director?

A: Directors don't see other directors a lot. When we're making films, there's only one director on that set. It's not like actors, working with other actors, or writers, who are working at home and can get together after work over coffee. If you're working in Rome and I'm in Mozambique, we can't just hang out. So what the Guild provides, apart from the many superb bedrock forms of support whose virtues are well known by its membership—creative rights, the pension plan, etc.—what I personally hold close is the society it offers of spending time with fellow directors. Whenever we get a chance to get together and talk, it is both rare and tremendously enjoyable. If Alejandro González Iñárritu wants to ask me about a certain cameraman, actor or actress, there are things I can reveal to him, regardless of the political sensitivities, which I wouldn't say to anybody else. I can always tell the unvarnished truth to another director. And I've enjoyed the same benefit coming the other way. There's a wonderful solidarity and truth-telling that goes on among directors.

Q: For years you were talking about doing For Whom the Bell Tolls, but more recently you've shifted your attention to a chapter in the life of photographer Robert Capa, set during the same time period. Is that an evolution of the same interest?

A: I'll be attracted to an arena or milieu for a long time, and I've long been interested in the Spanish Civil War. On For Whom the Bell Tolls, I was forced to realize that every aspect of the story has been so ripped off over the years and there's nothing left. There was no way for me to make it fresh, even though Hemingway's book is as brilliant as ever. I'm still interested in the period, and I'd long been interested in Capa, but his life story is so vast that there never seemed to be any way to do it until a few years back, when new information came to light about his love affair in Spain, in 1936, with fellow photographer Gerda Taro. It was a defining moment for him—the defining moment. His entire life changes from that point on and is never the same. That presented a way to tell the story. What next? There's a medieval movie I'm developing, that I really want to make, called Agincourt. There's a science fiction project I'd love to do. And some other things I can't discuss. Ask me in a week.