BY JEFFREY RESSNER

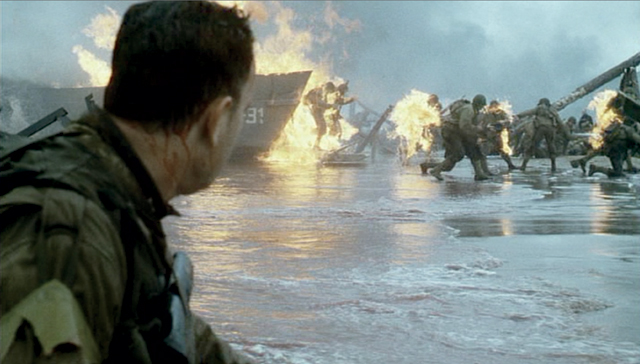

The harrowing 25-minute dramatization of World War II’s D-Day invasion that opens Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan is one of the most realistic battle scenes ever depicted on film. Shot over four weeks on a $12 million budget, the sequence used more than 750 extras and a cast led by Tom Hanks to recreate the Allies’ initial massacre and ultimate victory at Omaha Beach in Northern France. The remarkably graphic and haunting set piece helped Spielberg win the DGA Award and Oscar for best director in 1999.

The harrowing 25-minute dramatization of World War II’s D-Day invasion that opens Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan is one of the most realistic battle scenes ever depicted on film. Shot over four weeks on a $12 million budget, the sequence used more than 750 extras and a cast led by Tom Hanks to recreate the Allies’ initial massacre and ultimate victory at Omaha Beach in Northern France. The remarkably graphic and haunting set piece helped Spielberg win the DGA Award and Oscar for best director in 1999.

Because of restrictions and new construction at the actual historic site, the invasion was staged at Curracloe Strand on the east coast of Ireland. Striving to recreate the jarring, blurred look of 1940s photographs and newsreels, Spielberg and his longtime cinematographer Janusz Kaminski shot most of the picture using handheld cameras and came up with various tricks to give the scene a low-tech, documentary feel.

Spielberg eschewed storyboards or complicated shot lists. In fact, the original script condensed all of the D-Day action into about seven pages, without including too many specifics.

"I had to shoot this sequence one step at a time because that’s the way the Rangers took the beach: one inch at a time. As a result, I was able to make up this whole sequence as I went along," says Spielberg. “I don’t mean the whole history or the narrative of what happened on June 6, 1944, but literally to come up with shots on the spur of the moment and not a month ahead of time. It helped make things a little more chaotic and unpredictable."

This shot of the barriers known as ‘hedgehogs’ sticking out of the sand is the calm before the storm. It was a blustery day at 6:30 a.m. in the Dog Green sector of Omaha Beach, and the English Channel was a maelstrom. It was all waves and seasickness and waiting for the landing to begin. I wanted this shot to simply symbolize the calmest moment you’d get in the entire experience of watching this film. I also drained 60 percent of the color out of the movie; that was a foregone conclusion based on many tests I’d done with Janusz prior to principal photography. I didn’t want a Hollywood war movie in Technicolor; desaturation was the easiest way of taking the bloom off the rose.

This shot of the landing craft known as a Higgins boat was taken from a camera boat that we drove alongside to get various angles. It’s an important shot because it’s the first time we see the Higgins boat and it’s going into some pretty strong swells. As a result, I was able to cut from the [hedgehog] obstacles in the water in the shot that precedes it to the explosion of water against the flat bow of the ship, and it made for a really effective cut. There’s a geyser of water that just slammed against the boat and fired up into the air, which was a nice sort of way of introducing it.

This [establishing shot] was thanks to Tom Sanders and his great art direction showing the large encasement dug into the Normandy cliffs and the Vierville Draw [the beach exit road behind it.] I didn’t want to show the audience too much all at once; I didn’t want any one shot held on the screen for too long. I wanted them to be able to see things in increments, so that the impression was a large composite of horror and carnage, but the pieces would add up to good effect by the end of the 25 minutes. So in the foreground of this shot, the men jump over the side of the boat and the camera jumps over the side with them.

This was done on location in a little makeshift tank we constructed. We didn’t want the water to be too muddy, so we basically dug a large hole, waterproofed it with Visqueen [plastic sheeting], and filled it up with purified water just to get these shots. We wanted to show how the soldiers weren’t safe if they jumped into the water, that four feet of water over your head could not stop a high-velocity shell from going right through you. We had an underwater casing around the camera and a crane [set on a 40-foot flatbed trailer], so we were able to bring the camera up, submerge it, then bring it to the surface again. Instead of bullets, we shot pellets through the water that burst into blood bags.

Often the pellets wouldn’t go far enough but at least they gave us a really good reference so we were able to digitally augment the shot with a stronger visual of a projectile coursing through the water. What makes all of these shots work, however, wasn’t just the camerawork but also the sound design by Gary Rydstrom. He was being able to take you from the relative tranquility of being underwater, away from the din, and then suddenly you’re right in the middle of quadraphonic stereo that’s just blasting you. It was a real accomplishment of the sound effects editors.

Capt. Miller [Tom Hanks] finally makes it ashore, but a mortar shell exploding nearby basically rang his bell. I wondered what it would be like for him to observe these massive losses without hearing the screams or all the whistling shells, would it be even more horrific? Beyond the whole film shot handheld, I also wanted the camera to vibrate, with the image shaking to closely match the Robert Capa photographs of Omaha Beach that morning. To capture that chaos, I tested a Black & Decker drill taped to a Panaflex camera so the image would vibrate whenever I turned on the drill. It worked great, but thankfully we found a lens called the Image Shaker that did the same thing as my Black & Decker, only without having someone with a 90-yard extension cord running behind the camera..

I spend hours interviewing veterans of that moment and they said there was blood everywhere. The shore of Omaha Beach was red, the sand was red, the water was breaking pink and red. I was trying to honor the experience of what these veterans articulated to me. Their descriptions of the bloody beach really stuck in my memory—so that if Capt. Miller took his helmet that had come off and there was some seawater inside it, if he put the helmet back over his head it would be all bloody. We used a lot of blood on the beach, but fortunately it was all “Kensington Gore,” as it’s called.

I didn’t want to shy away from anything. So a moment like this, where a boy is holding in his guts and screaming for his mother is simply what it was like that day on that beach. The veterans of that moment often talked about how they couldn’t see the enemy, they couldn’t see where they were going, they were running with full packs, a very fractured experience. So to stage a sequence like this posed the question: Is this a John Wayne war movie or is this sequence representative of what the men who landed on that beach really experienced? I chose to acquit those factual experiences with imagery that I never censored or even questioned. My intention was to re-sensitize the audience.

This shot violated my original pledge to tell the entire story from the point of view of the Rangers. I was determined not to show the German Panzerschrecks [rocket launchers] and machine guns—yet I couldn’t help it, because it gave the audience some context about how easy it was for them to hit their targets, what appeared to be shooting fish in a barrel. Filming was complicated because there were so many squibs that needed to be planted in the ground. If we couldn’t get the shot done in two takes we’d have to come back the next day, because they would need the entire night to lay out two more takes worth of squibs. So there was a high cost for a shot like this, and good reason to get it right the first time.

I wanted to show how this all might have been an impossible mission, to show what little chance these Rangers had. The concrete encasements, the revetments, the Panzerschrecks were all so close. Then you’d have these mortars raining down on you, the German bazooka shells, the light machine guns, the barbed wire. You can also see several explosions, and Janusz came up with the idea of shooting with the shutter open to 45 degrees or 90 degrees, which completely negated any blurring. Often, when you see an explosion with a 180-degree shutter it can be a thing of beauty, but a 45-degree shutter looks very frightening.

For this shot of Barry Pepper as the sharpshooter concentrating and aiming at the Germans in the machine gun emplacement, I didn’t use a zoom or dolly or anything like that. It was camera operator Mitch Dubin holding the camera in his hands and just pushing it right down to Barry’s trigger finger and face. He just held the camera and walked right up to Barry; and it was all done the old-fashioned way.

Again we see the perspective from the German pillbox but I was now able to justify the point of view because some Americans had reached the top of the Draw. I shot through the barbed wire because that’s probably where the Rangers would be ducking in order to get out of harm’s way. I use foreground in movies quite often, whether I’m making a little romantic story, a historical drama, or a science fiction film. I just love foreground. It’s kind of like shooting in 3-D without using a 3-D camera.

The taking of the pillbox was interesting because I wanted to do this entire shot in a single take without a cut, which meant we had to do a lot of rigging so we could do three takes in a row. Again, if we weren’t able to get the shot in three takes, we’d have to set it up overnight and come back to do more the next day. We had to rig squibs all over the facade of the structure, and also have a flamethrower standing by. And all that black smoke? Well, we burned a lot of tires.

When the pillbox was blown up there was a lot of heat and chemicals that went off all at once. It was very intense for the stuntmen but, fortunately, it was a one-take wonder. Again, I used a 45-degree shutter on the explosions, and a 90-degree shutter on most of the running shots. But we alternated at times. Sometimes the 45-degree shutter would appear too exaggerated and the 90 turned out to be better. But for extreme explosions like this, where we really wanted to practically count each individual particle flying through the air, the 45-degree shutter worked best.

Early on I had asked my physical effects crew to rig our guns so that when they fired blanks they would also send an electronic signal to the squib in the Germans’ uniforms, so that the actual firing of the gun would trigger a particular squib on the target. It worked great throughout the entire movie, so if an M1 rifle was close to its target the squib would explode almost simultaneously, but if there was any distance there would be a millisecond delay to compensate for the bullet’s travel time before it hit its target. This shot is a good example of where the squibs were set off by remote control.

In addition to changing shutters and using handheld cameras throughout the shoot, Janusz also peeled the protective coating from the lenses, making them closer to the way they were manufactured in the 1940s. As a result of stripping that beautiful protective coating which makes the light look so nice, every shot seemed a lot more harsh without it. Every frame used these stripped-away lenses, and you can really see the effect from this frame with Tom Hanks’ eyes. There’s no glamour in that shot; it’s crystal clear. I was likely dollying into the close-up on tracks, using a 55 mm lens. We only used a few close-ups during the entire opening of the film.

This is probably one of the few crane shots in the whole movie. Before this shot, I wanted to start by showing the ebb and flow of the surf and so there were some cuts of all these bodies washing ashore. There were a lot of dummies used in this particular shot, including all the bodies in the water, obviously, because we couldn’t ask the stuntmen to hold their breath for that long. Nevertheless, this felt like a slick shot to me. Using cranes does tend to glamorize things and just makes them a bit more romantically slick. But I felt the audience might forgive me at that point and maybe even find that the slickness was a bit of relief from the harshness they had survived over the past 25 minutes.

The end of the shot brings us down so we can see the name ‘Ryan’ stenciled onto the back of the body’s kitbag. We used real fish—a lot of the veterans we spoke with recalled how the mortar shells went off in the water and just killed all these fish that would wash onto the shore. When I finished shooting on Omaha Beach I looked back on the four weeks that it took to shoot these 25 minutes and realized I might have sealed the movie’s fate by creating a sequence of such intensity people may not want to see minute 26. I imagined massive walkouts. But I didn’t want to mute it or make excuses for it. The movie was made for the veterans, and if I had done it any other way it wouldn’t have been anything close to resembling what they survived.