By Terrence Rafferty

There has always been a strong, stubborn streak of ornery independence in the American cinema, but during the studio era, when our movies were most popular, independent filmmakers were the invisible men—and women—of the art. When directors such as John Cassavetes, Shirley Clarke, Stan Brakhage, Kenneth Anger, and Maya Deren flickered into view, their work looked so different we barely knew what to call it. “Underground film” was one of the common appellations, and it was apt, because these movies surfaced only briefly, and when they did, seemed unaccustomed to the light.

But in the 1980s the independent film began, unexpectedly, to flower, and although the reasons for this burst of life are complex, it could be argued that it was all, really, an unintended consequence of the Reagan revolution. Hollywood’s studios, after a couple of decades of uncertainty and even some highly atypical risk taking in the late ’60s and early ’70s, got their swagger back in the early years of the Great Communicator’s feel-good administration. They were once again making money the old-fashioned way: by supplying uplift, sunny fantasy, and all manner of vicarious thrills—including, in their increasingly splashy action movies, the chest-swelling feeling that the USA was ready and willing to kick the world’s ass once more. Fists were pumped everywhere: in the gummy multiplexes and in the lushly carpeted offices of the studio executives. We were all Top Guns again. But not everybody thought it was morning in America.

Hence, independent film as we know it? Yes and no. Although it’s true that the almost berserk optimism and general triumphalism of the ’80s created a certain appetite for movies that might reflect a different, less rosy-hued vision of American life, it is also true—as always in the art of cinema—that economics and technology determined whether or not that appetite would actually be satisfied. And as it happened, the twin stars of economics and technology aligned properly at that point in time. For the producers and distributors of filmed entertainment, the popularity of cable television and the growing affordability of home video players (initially, the now quaint VCR) meant that they were going to need a lot more product to bring to the market. So while the major studios continued to chase after blockbusters, there was suddenly a place for (i.e., a way to make money on) lower budget pictures, and at least two distinct kinds of audiences for them. For the cable subscribers and home video omnivores, who are by definition not terrifically discriminating, cheap genre films would do the trick. For the more selective few, who were turned off by the loud action pictures and all the preview-tested happy endings, there was a different sort of movie altogether, something more intimate, more driven by character than by plot or spectacle, and (inevitably) more downbeat.

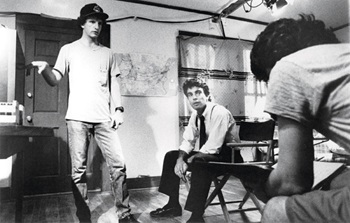

The latter species—the small-scale drama that aims to be the cinematic equivalent of a Raymond Carver story—is, usually, what we talk about when we talk about indies. But the fact is that the independent film movement as it exists today has always run on two tracks, a high one and a low one. At the high end were directors like Cassavetes, whose moody, black-and-white, shot-on-the-fly Shadows (1959) was an inspiration for younger moviemakers who wanted to tell tough-minded stories about actual people, and to tell them in their own way, without deforming the material to fit the studio mold. Still, not many movies of that sort reached the screen in the ’50s and ’60s: Cassavetes wasn’t able to make another film in the manner of Shadows for nearly a decade (Faces in 1968).

The low road had a lot more traffic. Independent companies such as American International Pictures and, later, Roger Corman’s New World Pictures delivered a steady supply of quick-and-dirty genre pictures, which were sometimes, within the constraints of their rigid for mulas, pretty lively and imaginative; but mostly they were just stuff to look at when you felt like sitting in the dark and letting some colorful moving images invade your weary brain.

In the ’70s, though, another route opened up—unmarked, poorly lit, and not to be traveled by the faint of heart—in the form of the midnight movie. The most famous example of which was, of course, The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975). Jim Sharman’s campy musical was in fact a studio picture that somehow escaped the confines of 20th Century Fox’s release plans and instead ran for years in special screenings in the dead of night, to a smallish but mighty enthusiastic segment of the moviegoing public: a cult. Rocky Horror’s brand of pansexual vaudeville wasn’t especially influential for either the studios or independents, but the movie’s out-of-nowhere midnight success was possibly the first indication that the audience was much more diverse than Hollywood had ever suspected. The existence of viewers who would pay good money to see their own non-mainstream sensibilities reflected on the screen was confirmed by the midnight triumphs of some genuine indies: John Waters’ trio of bad-taste transvestite farces, Pink Flamingos (1972), Female Trouble (1974), and Desperate Living (1977); and David Lynch’s hallucinatory domestic-horror picture Eraserhead (1977).

So when independent film began to race its engines in the early ’80s, in addition to a high road and a low road to take, there was this weird alternate route, a kind of permanent detour for those who had never been comfortable on the beaten track anyway. The Birth of a Nation of the high-road ’80s indies was almost indisputably John Sayles’ Return of the Secaucus 7 (1980), an inexpensive and simply shot comedy-drama about a bunch of unhappily aging ex-radicals. Visual style wasn’t really the point for Sayles, who was a novelist, any more than it had been for Cassavetes, who was an actor. Secaucus 7 is a writerly film, as Shadows was an actorly one, and in neither case is the language of cinema advanced even a little. But what Sayles’ movie showed, as Cassavetes’ had, was that a filmmaker could get some expression of his or her sensibility up on a screen without spending a ton of money—and if you had something interesting to say, an audience would find you.

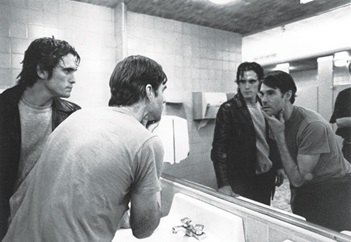

A few years later, the low road got its defining moment too in the form of Joel and Ethan Coen’s pulp noir Blood Simple (1984), which elevated—sort of—its down-and-dirty, Jim Thompson-ish material by means of witty plotting, elegant compositions, ingenious camera movements, and a wry, knowing tone. In a way, the Coens’ minor tour de force turned out to be more influential than Secaucus 7. The genre film with attitude—specifically, that attitude we later learned to call “edgy”—within a few years became an increasingly significant feature of the indie landscape, and for a good while after the international success of Quentin Tarantino’s violent and certifiably edgy thrillers Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994) it seemed practically the only landmark, looming over Indieland like that big hunk of rock in Monument Valley. Among the best of these nasty, low-budget genre thrillers were John Dahl’s Red Rock West (1992) and The Last Seduction (1994), neither of which, in truth, shared much of the irony and self-consciousness of the Coens/Tarantino aesthetic. Dahl’s pacy, precise directorial style is more impersonal—more like that of classical film noir. Even better was Carl Franklin’s Arkansas crime drama One False Move (1992), which was fearsomely violent but, thanks to Franklin’s calm, deliberative style, somehow transformed indie-thriller conventions into something approaching tragedy. Thanks to the new cachet of independence, these sturdy little genre pieces, which might have seemed too modest for a studio to bother with 10 years earlier, were allowed to come into the world, appear in a few theaters, and then live out the rest of their contented days on cable and video.

The higher, non-genre road is inherently more perilous: It’s a longer way down, and the guardrails aren’t always as reliable as they ought to be. From the early ’80s on, though, the support systems for the more ambitious kinds of independent films got steadily stronger. Small distributors such as Island Alive, Miramax, and The Samuel Goldwyn Company began to seek out low-budget independents, both for theatrical and home video release, and festivals such as the Utah/US Film Festival—later renamed Sundance—provided hunting grounds where the little critters could be tracked down and bagged. The festival began modestly, but by the late ’80s had become a major showcase and marketplace for independent film. By the ’90s, for two hectic weeks every January directors and hungry distributors choked the icy streets of Park City, Utah, and both big deals and big reputations were made there. Sundance even proved capable of generating the elusive, highly prized entity known as “buzz.” Its first major beneficiary, in 1989, was Steven Soderbergh’s kinky psychodrama sex, lies, and videotape, and a decade later that buzz helped turn a risibly inexpensive horror movie called The Blair Witch Project, shot on video by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, into a full-blown cultural phenomenon. A few miles down the road in Utah, Robert Redford’s Sundance Institute supplied financial and technical resources for filmmakers to develop their craft; and some distributors, notably Miramax, eventually moved into production as well. And because awards are the mother’s milk of the film industry, a new, indie-specific set of honors, complete with ceremony, was created in 1986: the Independent Spirit Awards.

With all this interest and activity, directors thrived. There were exponentially more opportunities, for directors of many previously underrepresented persuasions. Women such as Martha Coolidge (Valley Girl, 1983), Nancy Savoca (True Love, 1989), Kimberly Peirce (Boys Don’t Cry, 1999), Nicole Holofcener (Lovely & Amazing, 2001), and Sofia Coppola (Lost in Translation, 2003) got their chance, as did, to some extent, African-Americans, Latinos, Asian-Americans, and gays. And these representatives of what the Reagan crowd used to refer to as “special interests” were, in this new climate, able to make movies that actually drew on their own “special” experiences. Spike Lee’s charming 1986 sex comedy She’s Gotta Have It showed audiences a bit of America most of them had never seen: the lives and loves of young black people in Brooklyn. Jim Jarmusch’s deadpan Stranger Than Paradise (1984) performed a similar service for white hipsters in downtown Manhattan. Gus Van Sant’s first feature, Mala Noche (1985), gave viewers a funny, poetic look at the day-to-day existence of gays and illegal immigrants on the meaner streets of Portland, Oregon. It may be coincidental that all three of those pictures were shot in black and white, but in retrospect that choice seems strangely significant, because what the independents were doing harked back, in a way, to the beginnings of movies, nearly a century earlier, when everything the camera showed was something new, an occasion of awe and wonder. Seeing things you’ve never seen before was one of the original joys of moviegoing: These independents, with their special interests, allowed viewers to rediscover it.

In the three decades since the American independent movement came out of the shadows, a lot has happened and much has changed. Miramax was absorbed into the Disney studio for a long while, and other major studios established boutique divisions (some of which have now folded) for the sort of modestly budgeted films that could be marketed as “independent,” with the result that independent film is now largely a misnomer. It’s more an ethos—a vibe—than an economic reality. But it still serves the same function of providing moviegoers with something different, a product that feels handmade rather than machine-tooled. And the variety of what independent (or independent-like) directors have offered their viewers in the past 30 years has been staggering. There isn’t, and has never been, anything like a canonical indie style. How could there be? Idiosyncrasy, and even eccentricity, are in its DNA. Wes Anderson’s comedies Bottle Rocket 1996) and Rushmore (1998) are built around characters who are defiantly odd, and unlike Waters—who just turned the camera on his gang of Baltimore misfits and let them misbehave for him—Anderson emphasizes his people’s peculiarities with unusual angles and counterintuitive lenses. And in independent film, there’s no such thing as too weird. In Spike Jonze’s surreal Being John Malkovich (1999), characters rummage around inside the eponymous actor’s head as if this were the most natural activity in the world. There’s no such thing as being too marginal, either: In 1991, Richard Linklater had an indie hit with Slacker, in which he simply followed one young person after another doing absolutely nothing on the streets of Austin, Texas.

The temperamental resistance of independent film to anything resembling the tried and true wouldn’t, finally, be very interesting if it were confined only to character and content. It’s good to see people and places that haven’t been seen in the movies before, but after a while the quest for novelty gets old—and maybe a little desperate. (Even a filmmaker as resourceful as Jarmusch sometimes appears to be struggling to find people cool enough for his camera.) What has kept independent film lively in the past few years isn’t the subject matter. By now, we’ve seen just about everything, and for anything new that comes along we’ll probably catch it first on YouTube. The real secret of the indies’ continuing strength is the license the movement gives to formal experimentation, and the filmmakers whose work is most likely to last are those who have taken the most flagrant advantage of the freedom they’ve been offered.

The directing team of Scott McGehee and David Siegel, who began their career with the elegantly convoluted black-and-white thriller Suture (1993), and whose most recent film is the yet more head-splitting Uncertainty (2009), edit their movies in such a way that every scene turns into a kind of adventure in perception. They’ve developed a technique that deserves to be called Borgesian—all forking paths. Darren Aronofsky’s feature debut, Pi (1998), does something similarly unsettling, with the additional deranging element of wildly varying film stocks and grains. (It’s also in black and white.) Todd Haynes’ style from the start—the 1998 short Superstar, which used Barbie dolls to tell the sad story of Karen Carpenter—has been insanely eclectic and reliably unpredictable: It ranges from the jarring avant-garde theatrics of his first feature, Poison (1991), to the smoothly self-conscious pastiche of Douglas Sirk in the ’50s-set Far From Heaven (2002). If there’s a constant in Haynes’ work, it’s his devotion to the use of what Brecht termed alienation effects: formal devices that keep the audience at a slight remove from the emotion of the story. That’s so un-Hollywood it’s practically un-American.

Quite a few of the more audacious independent filmmakers, like Haynes, have relatively sparse filmographies. Their kinds of movies can be tough sells even now, after 30 years of out-of-the-mainstream American cinema. Even David Lynch has made only one feature (Inland Empire, 2006) in the past 10 years. The more prolific directors are the ones who have developed a singular, reliable style—a brand—as Jarmusch has, and those who keep their work fresh by changing their styles on a more or less regular basis. After sex, lies, and videotape, Soderbergh spent the next several years trying, it seemed, to make a completely different kind of movie every time he got behind the camera. By the time he got to The Limey (1999), he had amassed such a formidable arsenal of technique that he was able to turn a very straightforward revenge thriller into a dense, weirdly lyrical meditation on loss and memory. The editing, which moves backward and forward in time with exhilarating speed and ease, has the rhythm of its characters’ thoughts. And in the past decade he has continued to make movies of incredible variety, and at a blistering pace.

In a less obvious way, Van Sant has kept changing too and in ways that feel like deliberate returns to the sources of his inspiration. Since the gritty, poetic Mala Noche and its even more impressive follow-up, Drugstore Cowboy (1989), Van Sant has directed all kinds of movies, from the elaborate road-movie fantasia My Own Private Idaho (1991), to more conventional dramas such as Good Will Hunting (1997), to the satiric To Die For (1995), to the vibrant 2008 biopic Milk. But he always manages to come back, somehow, to stories about the misfits and outsiders of his native Portland, and it’s never the same. In his best movies of the past decade, Elephant (2003) and Paranoid Park (2007), Van Sant even goes back to the 4:3 aspect ratio of Mala Noche, which gives the films an unusual sense of intimacy, and he keeps shifting perspectives on the action—from one character’s point of view to another’s, from handheld video to film and back again. The light shifts constantly, and so do the moods. The camera will linger on an object or a face, then the action will pick up again, and then revert to a quicker rhythm. Experimenting restlessly, he moves down the road and keeps running into himself in different places. It’s what the independent movement was always supposed to be about: making your own private morning in America.

By Carley Johnson

With the growth of American independent film, the DGA has for many years recognized the unique needs of independent filmmakers. The Guild’s efforts began in the late 1970s and early 1980s when a number of indie directors joined the DGA after having worked on studio-financed projects. Because those members were still receiving offers for independently financed pictures, the DGA soon realized it needed to accommodate the different salary structure for these low-budget productions. Without a low-budget contract, those directors were faced with the difficult decision of turning down work or possibly resigning from the Guild.

“It was a tough fight internally and externally,” recalls then-DGA president Gil Cates. “We were chasing talented people away from the Guild. Someone might have thought, ‘Why should I join the DGA? If I have a chance to direct an Easy Rider, the Guild’s not going to let me make it.’”

So in 1984, under Cates’ leadership, the Guild took the initiative and negotiated an agreement with Cannon Films, then one of the industry’s most active production companies, in a move that would greatly impact the growth of low-budget motion picture production. A Variety banner declared “Cannon/DGA Pact May Spur Lo-Budget Pix,” and the landmark agreement with Cannon did just that. The two-tiered collective bargaining agreement provided an industry-wide impetus, and immediately opened the doors for any non-DGA independent production company to obtain the same kind of contract.

The Guild was then able to welcome into its fold independent directors such as Spike Lee and John Sayles, who up to that point had worked primarily outside of the studio system without DGA protection. Unit production managers and assistant directors who were members and had not been able to work on lower budget films also benefited from newly increased employment opportunities. The other guilds soon followed suit by negotiating contracts of their own with similar provisions.

But the evolutionary nature of the independent film landscape has required, and will continue to require, one key element for survival: flexibility. That flexibility was first manifested during the 1992 negotiations, which resulted in a revised, three-tier low-budget agreement, allowing for films under $5.25 million. In 1998, the Guild again responded to the burgeoning independent film market and changing economic needs of directors with an even more flexible, expanded four-tiered structure.

Today’s low-budget agreement is continually revised to keep up with trends and address the concerns of the independent film community. The current multi-tiered contracts now cover the production of narrative and documentary films with budgets of up to $11 million. The agreement has four tiers, the bottom and top tiers being divided into two sub-tiers in order to determine the AD/UPM scale rates.

“There’s an open dialogue with the producers so everyone continues to view it as a win-win,” said Associate Western Executive Director Jon Larson. “The DGA is not just an organization for directors who do big studio films.”

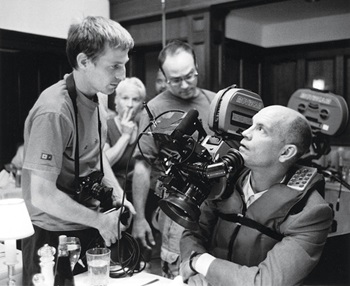

The Guild’s continuing efforts to help filmmakers realize their vision, regardless of budget, is supported by the Guild’s Independent Directors Committee (IDC). Formed in Los Angeles in 1998, with a New York branch added in 2002, the IDC was created to foster the creativity of the Guild’s independent film community. Founding IDC members Michael Apted, Steven Soderbergh, Penelope Spheeris, Stephen Gyllenhaal, and the late George Hickenlooper spearheaded a campaign to address the needs of members who work outside the major studios. “Members working in the independent, low-budget arena are invariably on the cutting edge and most vulnerable,” said Apted, the IDC’s first chair. ”Their rights need even more nurturing than those who exist in the public eye.”

The IDC provides a forum through which independent filmmakers can connect, share, and grow. “The Guild can be a haven for independent filmmakers,” said Soderbergh, a sentiment echoed by director Jason Reitman. “Personal filmmaking will always be vulnerable. As the landscape changes and the options drop from few to less, it becomes easier to consider settling when it comes to your directorial rights. Don’t be bullied. Independent doesn’t mean you have to stand alone.”