By Terrence Rafferty

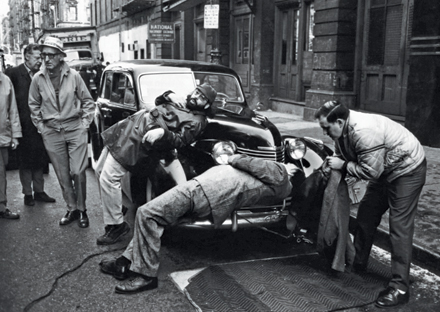

HIT MEN:Francis Ford Coppola shows Marlon Brando how to

HIT MEN:Francis Ford Coppola shows Marlon Brando how to

go down after he gets shot for a scene in The Godfather. By reputation the United States is a fluid, freewheeling sort of country, but change doesn't always come easily here. When the rules of the game for American filmmaking began to break down in the mid-'60s, the revolution was not bloodless. Fortunately, the blood was all on the screen. The Hollywood studio system, an assembly-line process that had been rolling sturdy entertainment vehicles out of its plants for decades, had finally started to show its age in the early part of the decade. You could hear the movies creak, knock, sputter. The once reliable stars were getting old, and so were the great directors: Hitchcock, Ford, Hawks, Wyler, Wilder, all of whom had flourished in the '50s but in the '60s appeared to be losing touch with their audience. Older moviegoers were drifting away to television, and younger ones—well, as the decade wore on and the war in Vietnam escalated and something called a counterculture came into hazy being, their desires became more and more incomprehensible to the Hollywood powers that were. Who the hell knew what those crazy hippies wanted?

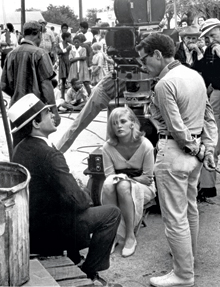

Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, with Warren Beatty

Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, with Warren Beatty

and Faye Dunaway, shocked audiences with its violence.

Probably not even the kids themselves could have answered that. But they knew it when they saw it. They knew when they saw Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde in 1967, Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider in 1969, and Robert Altman's M*A*S*H in 1970, each one a film whose success came as a complete surprise to the Hollywood suits, who were eventually forced to admit, for perhaps the first time in American movie history, that something was happening here and they really, seriously didn't know what it was. And this executive confusion was a golden opportunity for directors, who suddenly found themselves making films that would have been summarily rejected by the studios just a few years earlier. Some of these were financed independently, as Easy Rider had been. Raybert Productions (later BBS), the company that produced Hopper's freak blockbuster, used the profits to bankroll other unconventional films, like Bob Rafelson's Five Easy Pieces (1970) and Peter Bogdanovich's The Last Picture Show (1971). But the major studios, too, began greenlighting off-the-beaten-path pictures by younger filmmakers—Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets, George Lucas' American Graffiti, and Terrence Malick's Badlands all hit the screens, with studio money behind them, in 1973—and even, on occasion, entrusted a big-budget movie to one of these relatively untested directors. One happy result was The Godfather (1972), made by 33-year-old Francis Ford Coppola, who had directed four previous films but never had a hit.

The young directors were sometimes, derisively, called Movie Brats, but what they were, we can now see, was a kind of American New Wave, a homegrown version of France's Nouvelle Vague, which had a decade earlier overthrown the hidebound traditions of its own country's film industry. The French revolutionaries had grown up admiring American movies, a great flood of which had inundated Parisian cinemas in the years after World War II, but when they became directors themselves their films—intuitive, rueful, and personal—were unmistakably Gallic. Something of the sort happened in reverse when the American movie mavericks of the '60s and '70s, bowled over by films like Francois Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959) and Jules and Jim (1962) and Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (1960), found themselves behind the camera: although they borrowed a few techniques from the French New Wave, and had a somewhat looser approach to narrative, the movies are American to the core.

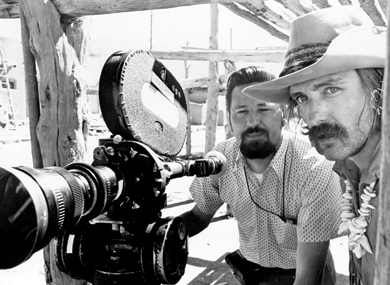

ICEBREAKER: Dennis Hopper (right) and DP László Kovács shooting Easy Rider,

ICEBREAKER: Dennis Hopper (right) and DP László Kovács shooting Easy Rider,

an early counterculture hit. After decades of the Hollywood studio system, the American New Wave needed the example and inspiration of its French predecessor, because our movie culture provided depressingly few models of independence. There were underground filmmakers like Stan Brakhage and Kenneth Anger, who mostly made short films; a handful of just-above-grounders who every now and then managed to raise funds for a grainy feature, notably John Cassavetes (Shadows, 1959) and Shirley Clarke (The Cool World, 1964); and small studios like American International Pictures (AIP), which churned out low-budget exploitation quickies for the drive-in trade. Each one of those wispy threads of cinematic freedom had some influence, particularly the last: Coppola, Scorsese, and Bogdanovich all apprenticed with AIP's top producer and director, Roger Corman; Brian De Palma's first thriller, Sisters (1973), was also produced by AIP. But although Corman's miserly, quick-and-dirty method of shooting a picture resembled, to some extent, the quasi-improvisational techniques of Godard, for the more ambitious of the younger American filmmakers simply making a movie, any movie, was never enough. They needed to express more of themselves than the economics of drive-in schlock allowed; they wanted to make art, just as the auteurs of the Nouvelle Vague did.

The movie that gave the first indication that such a thing was possible in American movies was Bonnie and Clyde, a film that on its initial release shocked audiences with both its unprecedentedly graphic depiction of violence and unusually volatile mixture of tones. Along with the gore, the picture featured a good deal of funky humor, romance (of a very peculiar sort), a measure of social commentary, and a soundtrack dominated by the incongruously chipper bluegrass of Flatt and Scruggs. It's an indication of the state of Hollywood in 1967 that the producer, Warren Beatty (who was also the star), initially offered the film to Truffaut, and later to Godard, and when neither of them worked out Beatty had the devil of a time finding an American director who could deliver the kind of movie he had in mind. He turned at last to Penn, a 45-year-old veteran of—as they used to say—stage, screen, and television, who had directed him in the eccentric, doggedly arty Mickey One (1965), and who had demonstrated a gift for violence in The Left Handed Gun (1958) and The Chase (1966). It was a fortunate choice.

Although it's difficult now to appreciate the impact Bonnie and Clyde had in 1967—explicit onscreen mayhem has become yawn-inducingly commonplace since then—the movie holds up beautifully thanks to its less obvious innovations: the weathered lyricism of the cinematography, the cunning alternation of long takes and quick cuts, the expressive use of slow motion, the discordant soundtrack music, the lightning shifts of mood. Telling the purely American story of a couple of real-life Depression-era bank robbers, Penn created a gangster movie that didn't look like any previous Hollywood gangster movie. It was a film that broadened the visual, aural, and, especially, emotional range of the genre, and changed the audience's expectation of how an American movie should make us feel. Truffaut couldn't have done better.

The film anticipates, too, a number of characteristics that would become hallmarks of our new movie style. After Bonnie and Clyde, for instance, filmmakers began to use music in a wholly different way. Easy Rider, released a couple of years later, has a score that consists entirely of '60s American rock, including Bob Dylan, the Band, the Byrds, Steppenwolf, and Jimi Hendrix; The Last Picture Show, set in Texas in the 1950s, employs the country music of that era, by Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, Bob Wills, and more; Mean Streets, wildly, mixes the Ronettes, the Rolling Stones, and Derek and the Dominos with long, heart-ripping passages from Italian opera.

In general, the newly empowered moviemakers exhibited a keener interest in sound than their studio-era forebears, experimenting with perilous levels of ambient noise and often using overlapping dialogue so fast even Howard Hawks might have had trouble keeping up. Between The Godfather and The Godfather, Part II (1974), Coppola amused himself with The Conversation (1974), an eerie thriller about audio surveillance in which the plot hinges on the recording (and interpretation) of a few seconds of overheard dialogue. Robert Altman, who was both the oldest and the most radical of the New Wavers, developed an extremely sensitive multitrack recording system that seemed to catch every mumbled aside, every far-off shout, every faint rustle of clothing in McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), The Long Goodbye (1973), Thieves Like Us (1974), California Split (1974), and Nashville (1975). Even if you didn't catch every word (and if you were in a theater with a mediocre sound system, you probably missed quite a few of them), the aural texture of these movies was extraordinary; they sounded as real as they looked.

And a heightened sense of reality was what all the American New Wave directors were after, whatever the differences in their styles and sensibilities. They were trying, in their various ways, to capture aspects of the country that hadn't been seen on screen before: like Wyatt and Billy, the bikers played by Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider, they seemed to be searching for an America that their generation feared was disappearing. "This used to be a hell of a good country," Jack Nicholson's character says in the film, and Hopper's direction, full of rapturous long tracking shots of Wyatt and Billy gliding through the Southwest and the South on their sleek bikes, gets high on the natural beauties of the American landscape. (In contrast, of course, to the small-spiritedness of most of the characters.) Easy Rider was set in the present day, in the overheated cultural climate of the late '60s, but more typically the New Wave directors looked for the American reality where Bonnie and Clyde did—in the past, the used-to-be. McCabe and Mrs. Miller is set in the late 19th century; Malick's Days of Heaven (1978), in the early 20th; Thieves Like Us, in the 1930s; M*A*S*H, Badlands, and The Last Picture Show, in the '50s; American Graffiti, in the early '60s; even Hal Ashby's melancholy 1975 sex farce Shampoo takes place in the bygone days of 1968. Taken together, these movies represent a kind of reinvention of the American historical film. They're reflections of the temper of the uncertain times in which they were made, both more elegiac and far less reverent than the "prestige" productions of the studio era.

The most remarkable examples of the new historical film were Coppola's Godfather pictures, which managed to turn the sordid lives of a Mafia family into a native epic of aspiration, betrayal, and intimate violence. Coppola's tone in these movies is cool, quietly observant of the manners and mores of a dangerously insular subculture; the wide shots give us a panoramic view of the Corleones' strange world, but the dark heart of the Godfather films is in the shadowy close-ups of Marlon Brando (in the first), Robert De Niro (in the second), and Al Pacino (in both), which seem to reveal both the seductions and the burdens of a don's peculiar kind of power. The rhythm of the editing—especially in The Godfather, Part II, which daringly shifts back and forth between the story of Vito Corleone's beginnings in Little Italy at the beginning of the 20th century with an account of Michael Corleone's intrigues and machinations in Nevada in the late '50s—is smooth, assured, almost preternaturally steady. (As it also is in The Conversation.) And in those days, when directors were starting to get more input into the final cuts of their movies, it was the rhythm that supplied the surest indications of the filmmaker's feelings about his material. Even if you'd missed the credits, the way a picture moved could tell you who'd made it.

There was no mistaking Mean Streets, for example, for a Coppola film, or an Altman. Scorsese's jangly, nervous editing rhythm is virtually the opposite of the Godfather films' serene flow, because his aim in that picture is not to guide his viewers along through a complex multigenerational narrative, but to unsettle his viewers, to keep them off balance—to give them the experience of the jarring unpredictability of city life. And when a 27-year-old prodigy named Steven Spielberg came along, in 1974, with an evocative Texas car-chase movie called The Sugarland Express, the jaunty, surprising rhythms of his cutting set him apart, too. Even when he's telling a sad story, as he is here, his editing has the wit and snap of silent-film comedy, on the large scale of something such as The General.

Except for Altman, who was too ornery and idiosyncratic to pay tribute to any of the filmmakers who had preceded him, the new directors weren't bomb throwers, really, just young artists who respected their elders but needed to find their own way, and to capture the late 20th-century American reality that the older generation either didn't understand or lacked the technical flexibility to represent.

But all was not well. Altman's post-M*A*S*H movies, even when they were as rambunctiously entertaining as Nashville, didn't do much business. Hopper, after the failure of his murky Easy Rider follow-up, The Last Movie (1971), didn't make another picture for the rest of the decade. Coppola went to Southeast Asia to shoot his ambitious Vietnam War epic Apocalypse Now (1979), and seemed to get lost in the jungle; he came back a year later with a flawed,

fascinating movie and a newly florid style. Bogdanovich (At Long Last Love, 1975) and Scorsese (New York, New York, 1977) had expensive flops. The energies of the counterculture were, in the natural order of things, slowly dissipating; the war in Vietnam was over, and that other long national nightmare, Watergate, had left everyone exhausted. And the most successful of the New Wave directors may have begun to feel, like Michael Corleone, the weight of their newfound power.

A sure sign, perhaps, that the American New Wave was running out of road were the indifferent receptions given to two of the decade's late masterpieces, Malick's Days of Heaven (1978) and Charles Burnett's Killer of Sheep (1977). Malick's film, a mournful Texas melodrama set in the early 20th century, is arguably the most exquisite refinement of the New Wave's outlaw historicism—it is to Bonnie and Clyde as Al Green's silky soul music is to, say, Otis Redding—and although it was generally well reviewed the movie died at the box office. Malick didn't make any another film for 20 years. Burnett's picture, a black-and-white low-budget feature about a working-class African-American family in Los Angeles, never even had the chance to fail commercially. It played at film festivals and on college campuses, but didn't have a theatrical release in this country until 2007. The movie, which Burnett shot over a period of years while he was in the UCLA film school, is as New Wave as the American New Wave ever got. It is episodic, impressionistic, and stubbornly lyrical, a movie that pauses to watch children at play, and—more important—to watch them watching their parents and other grown-ups. The kids don't know quite what to make of the world they've inherited, and Burnett doesn't tell them, or his audience, what to think, either. He's just looking himself, trying to make sense of things and catching some homegrown beauty on the fly. Killer of Sheep, like Days of Heaven, has the rhythm of a vanishing dream, but in a different way.

The American New Wave directors, like the sympathetic fugitives who were so frequently the subjects of their films, had a good run until the authorities—time and economics—caught up with them. In the late '70s, some of them managed to adapt their methods to the demands of commercial filmmaking, and had big box office hits: Spielberg's Jaws (1975) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), De Palma's funky, poetic horror movie Carrie (1976), Scorsese's noirish Taxi Driver (1976), and George Lucas' insanely profitable space opera Star Wars (1977) spring to mind. And other venturesome directors, like Jonathan Demme (Handle with Care, 1977), Philip Kaufman (Invasion of the Body Snatchers, 1978), Michael Cimino (The Deer Hunter, 1978) and the entirely sui generis David Lynch (Eraserhead, 1977), kept coming along to join the caravan.

The directors of our New Wave lit out like Wyatt and Billy in Easy Rider, to see what they could see, and find some out of the way places where America—and its movies—could be a little freer. The road didn't go on forever; even then, you could see the risk-averse blockbuster mentality looming in the distance. But they took us a long way, and in subtle ways their influence endures. They didn't blow it.