By Jeanne Dorin McDowell

When DGA member Todd Holland initially worked for HBO 19 years ago, first as director of the innovative Larry Sanders Show for six years and then directing episodes of the horror anthology series Tales from the Crypt, the pay television service was in its adolescence, so to speak. For directors like Holland, HBO offered the tantalizing promise of a distinctively unbroadcastlike environment, free of many of the rules and regulations that governed network television. The content was edgier, the language looser and directors were freer to explore darker themes, in comedy as well as drama.

"It changed my career forever in terms of how I viewed comedy," says Holland, who is directing Free Agents, a single-camera comedy on NBC this fall. "I've always had a darker sensibility in comedy so the fact that the content on HBO was edgy was very engaging to me. It was freewheeling, amazing.

"To this day the comedy on cable is different than it is on the networks," continues Holland. "It's hard to compare 30 Rock to Weeds. It's a dramedy in tone, but pay cable is the only place where they do it in a half-hour format. It's crept into network television now with shows like The Office, but for years the only place you got that dark humor was cable. The networks wouldn't touch it."

Holland's sentiments are echoed by numerous directors who love working for pay cable television because it gives them creative freedom and allows them—due to the subscriber business model—to take on subjects that are verboten on broadcast due to language and content restrictions. From The Sopranos and Dexter to Weeds and In Treatment, the number of A-list directors in both television and film who have migrated to cable is a testament to its ability to lure top talent.

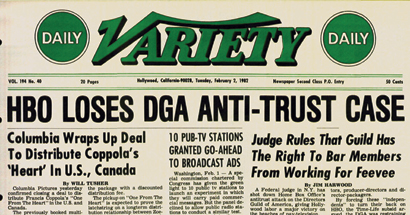

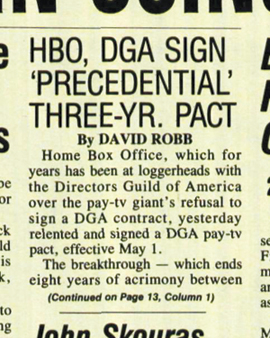

But the happy marriage that exists today between pay cable and the DGA has endured in no small part because of tough, often acrimonious, negotiations between the Guild and HBO, and the Guild's hard-won victories in 1981 at the bargaining table with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). From 1978 until 1986, when the Guild and the Time Inc.-owned pay TV service finally signed a precedential three-year pact, they fought over the DGA's right to instruct members not to perform directing services for HBO, on pain of disciplinary action. Although it took four years to ultimately come to terms, a U.S. District Court ruling in 1982 paved the way for peaceful coexistence.

The basic template for the eventual HBO deal was set in 1981 when intensive negotiations between the Guild and AMPTP over the issue of pay cable TV threatened to bring the industry to a halt. The DGA held out for pay TV formulas that ensured directors a fair piece of future profits in a growing industry. After weeks at the bargaining table, the Guild won an agreement that included an annual residual for directors based on the calculation of an applicable minimum multiplied by the pay service's subscriber count, plus pension and health contributions by employers. With slight tweaks, this would later become the foundation for the agreement with HBO.

A LONG STORY: Negotiations between the Guild and HBO

A LONG STORY: Negotiations between the Guild and HBO

started in 1978 and continued until 1986 with many chapters along the way.But to some degree, the prolonged negotiations between the Guild and HBO were also the result of growing pains. Founded in 1972 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, Home Box Office was a little-known pay TV service with a sports focus. The plan was to deliver recent commercial films, sports events and concerts to cable subscribers for a fee. The service was distributed by local cable operators, typically costing subscribers $6 a month, of which HBO received $3.50. That first year the service was elated to be airing a National Hockey League game from Madison Square Garden to 365 local subscribers.

But only three years later, through the advent of microwave technology, HBO was airing sports programs to thousands of homes where viewers were happy to pay for an opportunity to watch the heavyweight boxing championship fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier in Manila via something called a "satellite." In this way, HBO became the first company to use satellites exclusively as a means of transmitting programming.

During its first few years, HBO grew slowly as the cable industry struggled to get off the ground. Hampered by market fragmentation, lack of infrastructure and tough federal regulations, some of which were sponsored by the major television networks in an effort to prevent the nascent pay TV industry from accessing a portion of their audience and revenue, cable television was the little guy circling the major leagues. But in 1977 HBO turned its first profit, and the game changed. It also began its On Location comedy series and The Young Comedians Show, one of the first television forums for comedians such as Robin Williams and Paul Reubens (aka Pee-wee Herman). By 1982 HBO had 9.8 million subscribers, nearly 50 percent of all pay TV customers, and earned $100 million on sales of $440 million. In fact, HBO was about three times as big as its nearest competitor, Showtime. With big profits, the pay cable service was able to purchase top commercial films for subscribers, and by the 1990s original programming was also booming and directors were flocking to work on HBO series.

But back in the spring of 1978, the Directors Guild foresaw the bright future ahead for HBO and began negotiating for a contract to cover the terms and conditions of employment for its members on programs produced for pay television. "We are at the beginning of a second television revolution," said DGA National Executive Secretary Michael Franklin. "The first revolution began 35 years ago. The second television revolution brings us …pay cable channels, free cable channels, over the air pay TV services. No doubt in a few short years technology will bring us more satellites, more cable channels, more methods of reproductions of program fare."

In its infancy, Guild directors had worked on HBO shows for substandard payments with the understanding that this was a start-up business. Predictably, when the Guild and HBO sat down to start bargaining, the cable executives tried to make the case that their service was small and had an uncertain future.

"We were brand new and we didn't know what our business would be and the DGA was anxious to sign us up as if we were network television," recalls former HBO President Michael Fuchs, who was a senior vice president of sports during part of the negotiations with the Guild. "At the time we said, 'let's give this promising new business some air and let's find out what it's going to be.'"

Almost immediately Guild leaders recognized that it was necessary—in the verbiage of HBO's Tony Soprano—to go to the mat. At stake were the compensation and protection of directors at a point when pay television was in its infancy. The chance to get in on the ground floor of cable television on behalf of its members would never come again, and the DGA knew it.

Taking an aggressive stance, the Guild told its members not to accept jobs with HBO until an agreement had been reached because HBO was not a signatory company with a DGA agreement. In challenging HBO, the Guild was taking on the behemoth Time Inc., a publishing giant with deep pockets and battalions of lawyers dedicated to boosting the company's newest little cable TV business. In response, HBO filed two legal actions against the Guild, one with the National Labor Relations Board, the second an antitrust lawsuit in the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New York. "The lawsuit was our way of stalling to see what kind of business we had," says Fuchs.

In 1982, the Guild was vindicated in its position when in a stunning victory against HBO's antitrust lawsuit, Judge Abraham Sofaer of the Southern District of New York shot down all of the cable service's antitrust attacks on the DGA, giving the Hollywood labor union a major victory on the beaches of pay television. The judge ruled against HBO's allegations that the DGA's refusal to let members work for the cable service's program suppliers was outside organized labor's immunity from antitrust prosecution.

Four years later, after HBO had exhausted its appeals process, the pay TV service and the Guild signed a contract that called for all programs produced by HBO for pay TV services to be the subject of DGA minimums, residuals, and pension, health and welfare contributions, with the exception of HBO sports, interstitials and promotional programming.

Like a marriage that hits a bump in the road then moves past it with plenty of makeup sex, the rancor of eight years of labor negotiations quickly dissipated in the bliss of a bargaining agreement.

"We view this contract as of major importance to the industry," said then-DGA president Gil Cates. "On the Guild's part it will give our members an opportunity for employment by HBO where employment had been denied them. For HBO it will enable the world's largest pay television network to employ the world's most talented and creative directors and their assistants."

While acknowledging that HBO and the Guild "have certainly had our differences in the past," Franklin also hailed the new agreement as precedential, noting that it "reflects the culmination of our and HBO's efforts to achieve a fair and practical agreement."

Henry Schleiff, who was senior vice president of business affairs and administration for HBO during the eight-year negotiating period, points to the collaboration between HBO and directors today as the "fruits of the partnership" that was pounded out 25 years ago. Ultimately, says Schleiff, now an executive with Discovery Communications, the winner is the pay TV subscriber who can watch some of television's most creative programming. To directors like Holland, however, the big winners were Guild members. The DGA's decisive action and unwavering stance in the face of huge pressure opened the door to new creative and financial avenues on pay TV, opportunities that have only multiplied in the years since.