By Douglass K. Daniel

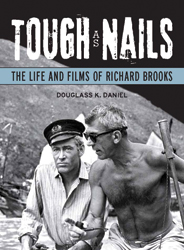

In recent years writer-director Richard Brooks has been making frequent, noisy walk-on appearances in other people's biographies, picking fights, yelling, being fantastically rude and abrasive, and prompting this reader many times to think, "Wow, I want to read his biography." Well, here it is, and it delivers. Not only do we get the very best/worst of Brooks' incredibly irascible on-set personality, we get to see beyond the barking autocrat and observe what several friends and co-workers call "the mischievous twinkle in his eye," which suggested that the other stuff was maybe all a nervous put-on. More important, author Douglass K. Daniel is cleareyed in his assessment of the enduring value and power of Brooks' best work. He discerns a director-writer who was state-of-the-art modern when he started out in 1945, but ended up an emblem of old-fashioned studio filmmaking, despite still inspiring young filmmakers with new work as late as his landmark docudrama In Cold Blood in 1967. He was an angry, working-class autodidact, a driven workaholic unsuited to family life, and a liberal-minded on-set tyrant who nonetheless inspired an abiding fondness among those who knew him well. Daniel depicts Brooks as a self-taught writer whose background in journalism and immersion in world literature determined the range of his concerns as a director. Thus we get the crusading-liberal tone of smaller-scale movies such as Deadline U.S.A. (1952), Blackboard Jungle (1955), and In Cold Blood along with logistically challenging—and not always successful—big-budget adaptations of literary masterpieces such as The Brothers Karamazov (1958) and Lord Jim (1965). His work remained politically alert and combative to the end (one unrealized late project was to have been a drama based on the 1950 DGA showdown between Cecil B. DeMille and then-Guild president Joseph Mankiewicz), but as a director, he grew to prefer adapting properties to generating original scripts. Dense with recollections from his co-workers and family—with some glaring lapses—including ex-wife Jean Simmons, astute and fair in its judgments, and eager to give Brooks a fair shake, this is the corrective account we have long required.

In recent years writer-director Richard Brooks has been making frequent, noisy walk-on appearances in other people's biographies, picking fights, yelling, being fantastically rude and abrasive, and prompting this reader many times to think, "Wow, I want to read his biography." Well, here it is, and it delivers. Not only do we get the very best/worst of Brooks' incredibly irascible on-set personality, we get to see beyond the barking autocrat and observe what several friends and co-workers call "the mischievous twinkle in his eye," which suggested that the other stuff was maybe all a nervous put-on. More important, author Douglass K. Daniel is cleareyed in his assessment of the enduring value and power of Brooks' best work. He discerns a director-writer who was state-of-the-art modern when he started out in 1945, but ended up an emblem of old-fashioned studio filmmaking, despite still inspiring young filmmakers with new work as late as his landmark docudrama In Cold Blood in 1967. He was an angry, working-class autodidact, a driven workaholic unsuited to family life, and a liberal-minded on-set tyrant who nonetheless inspired an abiding fondness among those who knew him well. Daniel depicts Brooks as a self-taught writer whose background in journalism and immersion in world literature determined the range of his concerns as a director. Thus we get the crusading-liberal tone of smaller-scale movies such as Deadline U.S.A. (1952), Blackboard Jungle (1955), and In Cold Blood along with logistically challenging—and not always successful—big-budget adaptations of literary masterpieces such as The Brothers Karamazov (1958) and Lord Jim (1965). His work remained politically alert and combative to the end (one unrealized late project was to have been a drama based on the 1950 DGA showdown between Cecil B. DeMille and then-Guild president Joseph Mankiewicz), but as a director, he grew to prefer adapting properties to generating original scripts. Dense with recollections from his co-workers and family—with some glaring lapses—including ex-wife Jean Simmons, astute and fair in its judgments, and eager to give Brooks a fair shake, this is the corrective account we have long required.

Review written by John Patterson.