By John Anderson

Melvin Van Peebles, balancing an unlit cigar between his fingers, is recalling the initial 1971 release of Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song—in two theaters in the entire country. Suddenly he excuses himself and leaves the room. A few seconds later he returns wearing a pinstriped jacket and vest.

"This is the suit I won off the Goldberg twins," he says, referring to Manny and Mort Goldberg, the Detroit theater owners who agreed to book his now-landmark movie, but only if they could include it on a multi-picture bill. "I wouldn't do it," the director says. "I wanted it to play alone and I knew it would work. I said, 'If it doesn't work, I'll buy you a suit.' They said, 'But there's two of us,' and I said, 'OK. And if I win, you give me two suits.'

Somewhere in Van Peebles' apartment on the West Side of Manhattan, there's another pinstriped suit. Sweetback's broke all the records at the Goldbergs' theater, on the strength of its title alone. Powered largely by word of mouth in the African-American community, it went on to make more than $4 million at the box office, in 1971 dollars.

Van Peebles may have won his suits, and started a movement, but blaxploitation—the overripe genre Sweetback's is credited with creating—was still something of a gamble, at least for the directors who made the films under hastily organized, usually low-budget conditions to exploit a suddenly "discovered" appetite for African-American heroes and black-centric stories. Just two years earlier, Easy Rider had altered the moviemaking landscape by proving that countercultural independent fare could make establishment-sized money. Similarly, Sweetback's showed that there was an underserved audience for black pictures, a need that was soon to be answered by the likes of Gordon Parks' Shaft (1971); Ossie Davis' Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970); Super Fly (1972), directed by Gordon Parks Jr.; Jack Starrett's Cleopatra Jones (1973); Jack Hill's Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974); and Michael Schultz's Cooley High (1975) and Car Wash (1976). The studios quickly got a clue. So did smaller production companies with such nostalgic names as American International Pictures (AIP), the Mirisch Company, and Motown Productions.

"Hollywood was dying on the vine," says Schultz, "and the blaxploitation films pumped new life into the whole Hollywood system."

No one questions that blaxploitation started with Sweetback's (followed quickly by Shaft). The story of a male prostitute who goes on the run after saving a Black Panther from racist cops, it was like nothing seen before in American independent films, let alone mainstream movies. But where blaxploitation ended is another question. Certainly, the original aesthetic—extravagantly fur-covered hotties; broad-brimmed hats; pimp rides; and pumping music—was largely a '70s phenomenon. But the influence of blaxploitation extended through the '80s—Schultz's hip-hop themed Krush Groove in 1985; Craig R. Baxley's Action Jackson, with Carl Weathers, in 1988; and Keenen Ivory Wayans' I'm Gonna Git You Sucka in 1988, which itself parodied the blaxploitation genre.

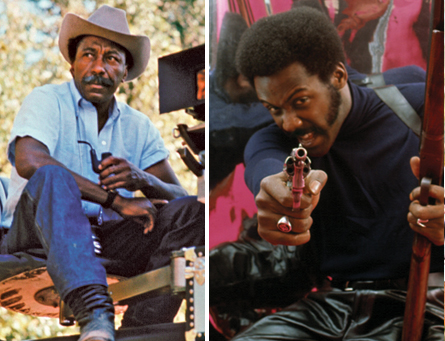

BLACK DYNAMITE: Gordon Parks directed Shaft at double speed;

BLACK DYNAMITE: Gordon Parks directed Shaft at double speed;

Richard Roundtree as the title character in Shaft.

But the real influence of blaxploitation is not limited to one decade or a single generation of filmmakers. In a 2006 story about Gordon Parks Sr. in the DGA Quarterly, Spike Lee said Shaft and Leadbelly (1976) were his favorite movies by the director, but it didn't even matter if you'd seen Parks' films. "Just the fact of who he was, what he did, that was the inspiration I needed," Lee said. "You get inspiration where it comes from. It doesn't have to be because I'm looking at his films. The odds under which he got these films made, when there were no black directors, is enough.

Despite the cash cow that black films became, the directors had to struggle against entrenched racism and a near-constitutional allegiance to business as usual.

"You were working on pictures that the industry had nothing but contempt for," says Hill. "There was a lot of racism in the industry, a lot of it was under the surface, but it was here. And the executives at the studios really had contempt for the audience they were making movies for. It was an uphill struggle to try to do anything really good."

Schultz told a story at a DGA event in 1999 about how AIP chief Sam Arkoff loved the idea for Cooley High, "but the rest of his people had no clue. They kept saying, 'Well, it doesn't have enough sex and violence in it. It's not going to work.' And when I started casting, they said, 'Garrett Morris doesn't look like a teacher. Can't we get Sidney Poitier?' "

SCHOOL DAZE: Making Cooley High, Michael Schultz was inspired by everyone

from Robert Altman to Ingmar Bergman, but most of the

executives didn’t have a clue what it was about.

The casting of a light-skinned black actress, he remembered, raised similar objections. "They said, 'Oh no, no way. She looks almost white!' I said, 'Well, we come in all flavors of the rainbow.' Although they didn't understand it and didn't know who these characters were, they eventually said, 'Go ahead.' But there was always that resistance."

Oscar Williams, who directed The Final Comedown (1972), said in a book of interviews, Reflections on Blaxploitation, "The film I had the most fun making was Five on the Black Hand Side [1973]. Because at the time [it] was made, the financial interests in that film kept on asking this question, 'Can a comedy about black people make it, because it isn't what's being done now? What's being done now is the angry film, with the violent main character going up against Whitey in the community.' So it was convincing [them] that it would work. And the film worked."

The producers of Cooley High, Schultz recalls, actually asked cast members if they minded working with a black director. "The actors were glad to get the work," Schultz says, a sentiment echoed by Hill, who is white. "There was such racism in the studios that the black actors were so happy to be working and playing something other than shoeshine boys or things like that," says Hill. "And that was a real pleasure for me to be working with actors who were so happy to be there. It was a revolutionary time in that sense."

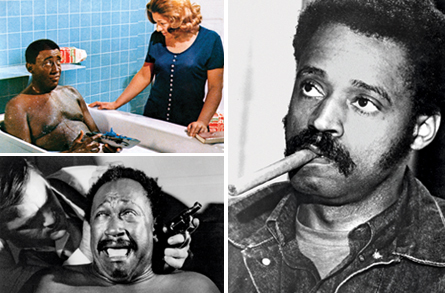

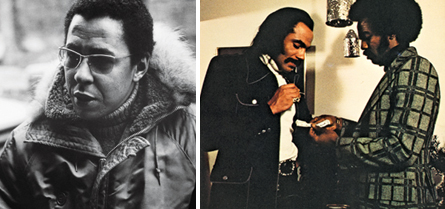

TAKING AIM: Melvin Van Peebles (right) started the blaxploitation genre

TAKING AIM: Melvin Van Peebles (right) started the blaxploitation genre

with the self-produced Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (bottom)

after

directing

Watermelon Man (top) for Columbia.

Certainly there was a sociological importance to the blaxploitation pictures—especially since a white studio system had been co-opting black content since the days of the pioneering Oscar Micheaux without sharing the work, or the credit, or much of the screen. But blaxploitation also involved the work of directors, and often under duress. Parks, in a 1972 interview for the DGA's Action Magazine, recalled having to fight to keep the Shaft shoot in New York, and to make the script work. "If I wasn't careful," he said, "someone was bound to discover the holes. So the thing for me to do was to make it as fast-paced as I could so there was no chance to see the holes. I played everything twice as fast as I normally would. I pushed my actors as fast as they could go. It helped them, especially the inexperienced ones, and gave better pace to the whole picture."

Parks, obviously, was ahead of his time—the pacing of movies today is a relative blur—but such was the aesthetic that ruled blaxploitation pictures. "The studios wanted action, action, action," says Hill. "But that's not what works. You have to have balance and pacing, in order to have that violence mean anything. You have to care about the people being subjected to it."

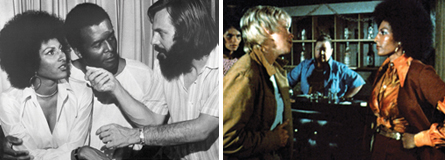

FOXY LADY: Jack Hill (left), working with Pam Grier, wrote the part for

her and

insisted on casting the actress in Foxy Brown (right) over studio objection.

Sex and violence were usually a part of the blaxploitation stories, and the music helped create the style and swagger of the genre, and unquestionably enhanced the chances for the films to cross over into a mainstream audience. You would have had to be living under a rock in the '70s to not have heard the theme to Shaft or the title song to Car Wash. When Isaac Hayes was brought in to write the theme for Shaft, Parks described the main character and told him that the music had to familiarize the audience with him. Shaft was a flashy private eye hired to find the kidnapped daughter of a Harlem gang lord. In the title song that opened the film, Hayes' lyrics set the table for the action and unforgettably described the hero as "the black private dick/that's a sex machine/to all the chicks." Enough said.

The role of the director in fashioning the music for the blaxploitation pictures varied. When Schultz did Cooley High, he recalls, "I could use any Motown songs I wanted, and at the time nobody really valued Motown's music; I got 17 classic Motown songs for the film for almost no money."

Car Wash, he said, was a totally different animal. The producers had initially gotten Universal to invest, and this allowed them to hire famed songwriter Norman Whitfield. "They actually hired him to do the music before they hired me," Schultz said. "They said, 'We hope Norman is OK with you, because we think he's great.' 'Are you kidding? He wrote half of the classic Motown library.' So Norman and I sat down before we started shooting and I told him the kind of numbers I wanted, because I wanted to shoot to the music."

Van Peebles, who self-produced Sweetback's, and had more control than resources, lucked out when the unknown band he hired turned out to be the soon-to-be-discovered Earth, Wind & Fire. Van Peebles scored the film himself, using his own system of musical transcription that involved numbering the keys on a piano, middle C being "1."

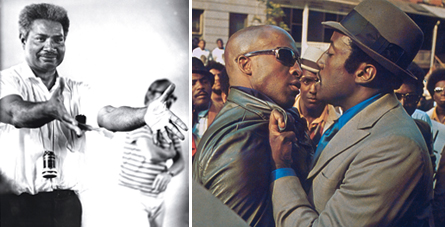

UPTOWN: Ossie Davis (left) combined comedy and action in one of the

first blaxploitation pictures, Cotton Comes to Harlem.

Van Peebles never went to film school. "I just knew it was the way I would see it, and a lot of it became de rigueur." But he paid a price: He lost the sight in his right eye while editing multiple images on top of one another and viewing them through the wrong end of a now obsolete editing machine. In addition, he couldn't shoot certain scenes after dark, so he colored the stock footage to simulate night—a tactic of early silent films, but something Van Peebles may as well have invented.

"There was no possibility of doing other things. That's how that effect was introduced. Necessity is the mother of invention," he says, then smiles. "A bumblebee can't fly. He's aerodynamically unsound. But he doesn't know that."

Van Peebles told people he was shooting a porno film "because the only place I could find capable technicians was in the porno industry, people who knew what they were doing." And playing the lead character wasn't his original plan. "That wasn't the idea at all, but every actor who knew one end of the camera from the other wanted more lines," he says, laughing. "Sweetback only has three lines in the whole movie. They'd say, 'I can't do this, write more lines.' I said, 'Go fuck yourself.' "

As much as the genre was known for its macho male characters such as Shaft, the women also had a powerful presence. Hill wrote Coffy, the story of a nurse who goes on a vigilante mission against the junkies who turned her sister into an addict, for Pam Grier and insisted she play the title role. For Foxy Brown, Hill also insisted on Kathryn Loder to play the weird sister Miss Katherine opposite Grier. Both Loder and Grier had been in Hill's The Big Doll House (1971), a women-in-prison picture that helped him get the assignment to direct Coffy.

For instance, he shot Grier from inside a closet in one scene from Foxy Brown because he was filming in an apartment too small to accommodate the camera anywhere else. When asked about "self-expression," Hill demurs. "I used camera movements for specific reasons," he says. "When you have light, the way it is under the freeway in L.A., where we shot scenes for Coffy, we used a lot of lateral camera movement because there were a lot of columns, and when you move the camera laterally it creates an effect of depth, sort of three-dimensional. I wouldn't call it self-expression exactly; you move the camera when you have reason to do so."

Some of the blaxploitation directors, Schultz in particular, were affected by what was happening in contemporary film at the time. "In Cooley High, I took some elements from an Ingmar Bergman film and kind of patterned the classroom scenes after something Bergman did," explains Schultz. "With Car Wash, I had seen Robert Altman's Nashville and I loved what he was attempting to do in that. He was telling stories in depth, but instead of one at a time he had one in the foreground, one in the background, and when I read Car Wash, it seemed like a perfect vehicle for the same kind of thing Altman did in Nashville." In addition, the omnipresent radio—which creates a sort of Greek chorus throughout the film—echoed the PA system in M*A*S*H. "Car Wash was kind of a secret ode to Altman," says Schultz.

At first Schultz had no idea how to make movies. "The blaxploitation era happened just as I was graduating from theater school and moving to New York," he recalls. "I was going to get involved in theater and then Melvin Van Peebles showed up and all these copycat movies, some much better made than others."

When he saw the films he thought, "Wow, it's possible to do this. I said, 'Oh, I could make better films than this.' I knew actors, and I knew story. I just needed people who knew what they were doing so I'd be doing the right thing with the camera."

Schultz, who continued to work extensively in television, said both Parks and Van Peebles were enormous influences, and the main inspirations for a generation of black—and blaxploitation—directors. "I admired the way Melvin was approaching the craft. Even though he says he didn't know what he was doing," says Schultz, "he knew exactly what he was doing."

COOL DUDE: Following in his father’s footsteps, Gordon Parks Jr. directed Super Fly

with Ron O’Neal as a coke dealer looking to get out and go straight.

But despite the box office success of Sweetback's and ushering in a new style of filmmaking, Van Peebles said he became "persona non grata" in the industry. After directing Sweetback's, he lost the three-picture deal he'd gotten at Columbia Pictures. Although he opened the door to black heroes and black-made movies, the welcome mat was yanked out from under him.

Hill got a similar reception. "Making these so-called blaxploitation films—which weren't called that at the time, they were just called black pictures—directors got so stereotyped," he says. "Even more so than actors. And having made those films, albeit very successfully, people saw me as a director of black pictures." Even though Coffy worked its way up to No. 1 at the box office, "the answer was, 'It's a black picture and it doesn't count.' "

Over the years, with the appreciation and affection for the genre growing, Hill and the other blaxploitation directors have gotten a measure of recognition for what they created. "The irony of it all is that nowadays, and in the past 10 years or so, people are looking at these films as having real historical significance," he said. "So I feel that I helped show that black characters and black life could appeal to a broad general audience and brought those things into the mainstream of films. I feel vindication nowadays because they're taken so seriously."