BY JEANNE DORIN MCDOWELL

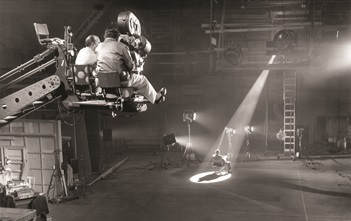

LIGHTS, ACTION: In 1955, the Guild participated in a series of live

LIGHTS, ACTION: In 1955, the Guild participated in a series of live

dramas, the Screen Directors Playhouse, directed and introduced

by prominent members. (Credit: DGA Archives)

It was the early 1950s and Arthur Hiller was directing a live drama with actor Darren McGavin for Matinee Theatre when two actresses in the scene forgot their lines. This was the sort of thing directors dreaded. "Darren carried the scene for about five minutes by himself," Hiller recalled in a recent interview. "I was in the control booth and the associate director was on the floor. He was running behind the actors with the pages in his hand, trying to stay out of view of the cameras and give the lines to the women.

"You had to be on your toes," continued Hiller, a former DGA president whose career eventually took him to features. "There was no safety net. You couldn't do a second take and there were so many things that could go wrong. Furniture was always getting in the way or somebody was tripping or forgetting their lines. And even when you did your job really well, it was tense; there was always the possibility of all those things going wrong."

Ask any director who worked in live television in the late 1940s and early '50s, and he will undoubtedly have a similar anecdote (or many) to share. In its nascent decade, the miraculous new medium posed daunting challenges for young directors. There was no blueprint on how to direct, and the director's job within television production was still being defined. The technology wasn't yet up to speed. Cables attached to large, clunky cameras snaked across the floor. The men—and they were mostly men—who ventured into directing television were cowboys of sorts, finding new techniques and methods for working in a hybrid medium that borrowed elements from theater, radio, and film. Oftentimes, they figured things out on the fly.

"You had to have the guts of a blind burglar and the coordination of an athlete," director Arthur Penn said in a 2006 DGA Quarterly interview when asked about the qualifications of a TV director in the early years. "It was tough. Quite a few guys ended up sick from it."

"A lot of people couldn't handle the pressure," echoed Charles Haas, who directed Lucky Strike's Your Show Time in 1949, which was the first dramatic series shot on film instead of broadcast live; The Hardy Boys on ABC from 1955-1957; and a number of successful '60s series such as The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and 77 Sunset Strip. "On one filmed drama I directed, the female lead got sick, and I ended up having to shoot 17 pages of script the following day. It was inconceivable to figure out the complex setups. Typically, I'd get a script and break down the whole thing on the train going home the night before, then be at work by 7 in the morning. I'd give the first setup to the cameraman, and we would start shooting by 8 a.m."

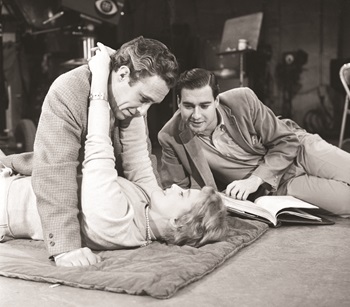

John Frankenheimer, directing Playhouse 90, preplanned all his shots.

John Frankenheimer, directing Playhouse 90, preplanned all his shots.

Sidney Lumet, working on Danger, was known for a "lightning quick"

method of shooting. (Credits: CBS/Landov)

For all its stressors, however, directing television in the early years was as exhilarating as it was nerve-racking. The challenge, much as it is today, was to figure out how to tell a story visually. But because it was a new frontier, a Wild West, directors also had the freedom to learn and experiment as they went along. Although no one was getting rich (Haas remembers earning about $55 a week in the late '40s), many of the medium's first directors were instantly smitten; they developed techniques that paved the way for the next generations of television directors. Sidney Lumet, who directed original dramas for Kraft Television Theatre and episodes of the popular half-hour anthology series Danger, which aired from 1950-1955, was known for developing his own "lightning quick" method for shooting to satisfy the high turnover television required.

"Directors were nervous, some more than others," said former DGA President Gene Reynolds who, as an actor, worked with Lumet in the '50s and went on to direct M*A*S*H and many other shows. "Sidney was amazing in being able to handle all that tension. He was a very good director, interesting and fun to work with. But it was a sweaty proposition, and no one worked coolly."

"What was so interesting about this so-called golden age was that no one knew it was a golden age," Lumet said in an interview for the DGA's 50th anniversary. "It was so early that there was nobody to say no; there were no rules yet, which is probably why so much good work came out of it."

A number of the emerging directors had been introduced to the craft while in the service during World War II. John Frankenheimer, for example, helped make Air Force documentaries for a newly formed military motion picture squadron in Burbank, then went to CBS on the suggestion of a friend in 1952. He worked as an associate director for Lumet on Danger and went on to direct more than 125 live television shows including 42 episodes of the 1956 groundbreaking anthology Playhouse 90. Television directing, he said, taught him many of the techniques he later used in features such as The Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days in May. "I learned a great deal about cutting in live television," Frankenheimer said in a 1970 interview for the DGA's Action magazine, "because, after all, the live television director certainly had the final cut. That's what went out on the air."

But to accomplish this required careful planning, added Frankenheimer. "All of our shots, contrary to what some people thought, were always preplanned. Some directors preplanned all their shots before they started rehearsals. I didn't. I would rehearse and work with the actors for about a week and a half and then I would decide how I wanted to shoot the show. What we in essence were doing on the air was functioning as film editors—I mean deciding what was going to be in close-up, what was going to be in a two-shot, where we were going to dissolve, what was going to be in master shot and so forth."

Out of this sense of discovery came a camaraderie among directors, who swapped information with one another and shared ideas about what they were doing. And directors were part of the close-knit team of stagehands, cameramen, engineers, floor managers, and actors. "We were all learning together, and you could try anything if you wanted to," former director and television historian Ira Skutch said in a 2006 interview with the DGA Quarterly. "It was almost like being back in college, that kind of spirit where everybody does something together."

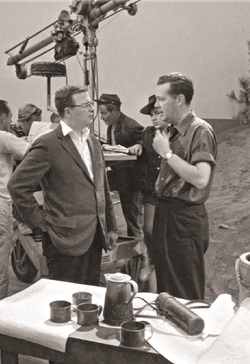

PLANNING: Del Mann (right), who turned his TV production of

PLANNING: Del Mann (right), who turned his TV production of

Marty into a feature, overcame what he called "a kind of rigidity

of shooting" due to technical limitations. (Credit: DGA Archives)

Although early television was similar to theater in that it unfolded in real time, the potential for complications was compounded by the limitations of the technology. There were no zoom lenses, which meant directors had to get off one camera and move to another one (if there was another one) in order to change lenses. At the same time, directors were trying to orchestrate performances and monitor what was happening in front of the camera between actors. "It was an emerging medium," recalled Penn, who started in live television as a floor manager before becoming one of a handful of rotating directors on NBC's The Philco Television Playhouse in 1948. "Every couple of weeks we'd get another little technological advance, like the zoom, or steadily improving sound."

Introduced to the masses in 1946, television struck a chord among Americans who were readily hooked on the excitement and immediacy of receiving nightly dramas and comedy through an odd-looking rectangular box in their living room. They were seeing the drama on the screen at the same time it was being shot live in production. Since the FCC required local stations to fill 28 hours a week of television over 52 weeks, the new medium had an insatiable appetite for programming. Besides some early filmed comedies such as The Life of Riley and The Burns and Allen Show (both taken from popular radio programs), much of the early programming consisted of storytelling and live dramatic adaptations drawn from books and short stories. During the 1946-47 season, for example, Television Theatre aired full-length three act plays on many Sunday evenings. Kraft Television Theatre, which premiered in 1947, was the first hour-long dramatic series on television that aired regularly each week. In 1952, a push for original live one-hour and half-hour dramas took television to a whole new level and ushered in the creatively rich era of live drama that lasted until about 1959.

With live drama dominating the uncluttered airwaves, it was logical that directors were recruited from radio and theater. Many began as floor managers and then became associate directors. Over time they moved up to director when the network deemed them ready—or when an illness or emergency left the director's chair empty. Fred Coe, a theater-trained Yale graduate who wanted to work in television, got a job with NBC and within a month was directing a late afternoon children's show. David Pressman, a director and acting teacher at New York's Neighborhood Playhouse in the 1930s, moved into television as the director of Actor's Studio, a live half-hour dramatic series that ran from 1948-1950 on NBC and was the first television program to win the prestigious Peabody Award.

"What captured my imagination was that here [on television] you had the opportunity of editing and staging at the same time," Pressman said in an interview for the Television Academy archives. "This was a unique experience. Here you were using three or four cameras at the same time…. I would call up Yul Brynner, who was a CBS director, and ask, 'How did you do that?' We all discovered how to do television live from 1948-1952."

But each network—NBC, CBS, and DuMont (which was eclipsed in 1948 by ABC)—defined the job of director differently and had its own distinct corporate culture and policies regarding the chain of command on shows. RCA-owned NBC, which was known for cultivating a stable of writers such as Paddy Chayevsky and Rod Serling, had a strict policy whereby the director on a show was permitted to talk to the technical director only through the cameraman. As Frankenheimer remembered, the job of associate director at NBC was a lesser position than at CBS, where associate directors were like cinematographers and responsible for preparing all the camera shots for the director as well as myriad technical tasks. That was probably because the director ruled supreme at CBS and had ultimate control over the look of a show. The network even encouraged and reimbursed associate directors for attending live theater in New York, regarding it as a way for them to learn about directing.

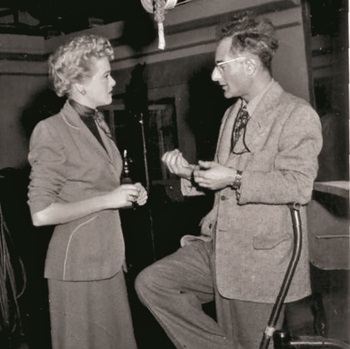

PROBLEMS: Arthur

Hiller, directing Goodyear Theatre, knew anything

PROBLEMS: Arthur

Hiller, directing Goodyear Theatre, knew anything

could go wrong. (Credit: Photofest)

Charles Haas, directing Big Town, says "a lot of people couldn't handle

the pressure." (Credit: Courtesy of Charles Haas)

The first model for television directing in the 1940s was borrowed from live radio: Instead of working on "the floor"—which is where the director was stationed for films, theater, and eventually television—the earliest TV directors were situated in a control room, sometimes just down the hall. Cameras, and there were typically three, occasionally four, were set up in a cramped space that had often been used for radio. Studio cameras, with their rotating lenses, allowed directors flexibility when it came to deciding on the shots they wanted. But it also made the director's job considerably harder because he had to instruct the cameras where to go next.

Martin Ritt, who was just out of the Army when he got his first job at CBS, recalled the logistics like this in a 1985 DGA interview: "They had one studio in those days; it was like Grand Central Station. We did a show every week with one camera. There was nothing in reserve. If the camera went bad, that was the end of the show. When we'd finish a scene on one set, sometimes the operator had to run the entire length of the studio to get to the other set and we had to go black sometimes for 30-40 seconds. Sidney Lumet was my AD and next door [John] Frankenheimer and [Robert] Mulligan were directing shows. It was really an exciting time."

The technical limitations were also obvious. After a while, CBS and NBC used three cameras on a show, one of which was mounted on a Fearless camera dolly, the other two on custom built pedestals that were raised and lowered with air pressure. "NBC's restrictions on equipment and so forth were much more rigid than a lot of the others," Delbert Mann, who directed Marty first for TV and later as a feature, commented in the book The Days of Live, edited by Skutch. "You could not dolly a pedestal camera, because it was too big, too awkward, too difficult for the cameraman to do it smoothly, keep in focus, and follow the action. You simply had to plan for static shots from your pedestal cameras and mobile shots from your crane camera. So there was a kind of rigidity of shooting that became almost mandatory."

Making matters even more complicated was the lighting. CBS used fluorescent lamps for base lighting; NBC used incandescent flood light bulbs arranged in banks of six to 12. Since 800 foot-candles of light were needed for a quality picture, temperatures in production studios were often intolerable. "You'd spend a day in the studio, and they had these old iconoscope tubes, so the studio would get up to 110, 115 degrees," said Skutch, who worked as a floor manager at NBC in the late '40s. "One day the art director brought in a bell jar with wax fruit in it for a living room scene, and at the end of the show there was nothing but a puddle of wax at the bottom."

Directors were also grappling with a hybrid medium that required adapting techniques common in theater and film. The TV dramas were similar to stage productions, but they were nonetheless interrupted by four or six commercial breaks (as opposed to one or two intermissions in the theater). Rehearsals were not only about blocking actors, but figuring out camera moves. And, as in movies, every shot was framed, shaped, and choreographed by the director and his cameramen. Live TV had close-ups, fadeouts, crane shots, two-shots, over-the-shoulder dialogues—all movie techniques—except that the cameras were attached to small tractors and lacked zoom lenses. If a cameraman or actor missed his mark, the result could be a blurry image for the viewers at home.

"Every shot was purposeful and meaningful and all had a place in helping tell the story properly and giving it the sophistication it needed," said Ted Post, who directed some 700 television episodes including Danger, early Westerns such as Gunsmoke and Rawhide, and Peyton Place, which in 1964 became television's first primetime soap. "It was shaky in the sense that you had to hit your mark. On one show I directed, Eli Wallach was so frightened that he would always look down at the mark. I kept saying, 'Eli you mustn't tell the audience you're hitting a mark!' But everybody was concerned about that."

The pace was also grueling, and directors quickly learned the importance of rehearsals. Usually several directors were hired by a network and rotated episodes on live dramatic shows. A director had about 10 days to rehearse for a one-hour drama. If it aired on Sunday, the following morning he was casting the next show, then spent a few days working with the writer and was back in rehearsals again five days later for the next performance. Haas, who directed the popular series The Millionaire, recalled the pressure from the network. "If you were running late they would send one of the executives out to the set to raise hell with you."

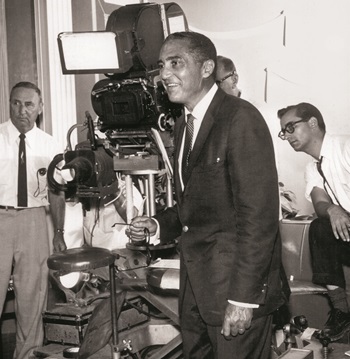

NEW TRICKS: Sheldon Leonard, started out working on single camera

NEW TRICKS: Sheldon Leonard, started out working on single camera

shows, but welcomed the rehearsal time of a multiple camera setup.

Like doing a play, he said. (Credit: DGA Archives)

In 1951, as the New York television scene exploded with live dramatic presentations, the premiere of the comedy I Love Lucy led the way for an alternative filmed approach to television that was developing on the West Coast. Lucy, which was created and produced by Desi Arnaz under the banner of Desilu Productions, adapted a three-camera studio system for live television shot on film. Using 35 mm cameras, the sitcom's proscenium-stage performances were filmed from the unconventional perspective of a live audience. Rather than the standard light-block-rehearse-and-shoot, one set and one setup at a time, which was the traditional way film was used, the director now planned scene by scene and filmed the action in continuous takes, which he later assembled in postproduction. No longer did a director call the shots from the control room but could be out on the floor with the actors and the rest of the crew. The need for instant cutting and editing became obsolete, and by the time videotape was introduced in 1956, television directors were able to select the shots they wanted during final edit, correct or discard bad takes in the editing room, and use extra footage that had been shot from another camera. Postproduction became a major tool in the TV director's arsenal.

Sheldon Leonard, who started out working on single camera shows, made the switch to a multi-camera setup for Make Room for Daddy with Danny Thomas. "At that time I Love Lucy was the only multi-camera show," he recalled in an interview for the DGA's 50th anniversary. "I had to learn the multiple camera technique, which turned out to be relatively simple, and also gave me opportunities I would not have had otherwise. For example, the opportunity to develop a show the way you develop a legitimate stage play, with a four- or five-day rehearsal period before you commit to film."

By the late 1950s, a lot of television production had moved permanently to the West Coast, which became the center for episodic comedies, sitcoms, and dramatic programming, both on film and tape. New York remained the center for sports programming, news, and live events. Meanwhile, the role of the director changed dramatically and the initial phase of experimentation and discovery in television gave way to an adolescence marked by experience and technological advances. Free from many of the demands of live television, directors were now able to concentrate more on the performances of the actors, pacing, and the aesthetics of directing. "When directors came West it changed the nature of the content of television," said Reynolds, who won two DGA Awards and three Emmys for M*A*S*H. "Directing was gaining more finesse. When we worked outside for M*A*S*H, for example, cameras were actually more flexible by this time and we had handheld cameras. It had a big impact in terms of our technique of directing."

But for the directors who cut their teeth on early television, the initial rush of discovery was never forgotten. Years later, when Frankenheimer had made his mark as a film director, he recalled his own sense of excitement directing television in its first decade. "We all loved it," he said. "If live television were still around the way it was when it was really live we would have preferred it to movies. I don't know how to explain the feeling you have as you're going along and it's working—and isn't working. So many emotions and feelings in one hour or an hour and a half."