BY AMY DAWES

CLOSING THE DEAL: (left to right) Negotiators Ernest Ricca, Joseph

CLOSING THE DEAL: (left to right) Negotiators Ernest Ricca, Joseph

Youngerman, unidentified, and Jack Shea iron out the details of

the merger in New York. (Credit: Courtesy of Jack Shea)

The advent of the television industry in the 1940s and '50s transformed Hollywood and grew the Directors Guild into a bigger, sturdier union—with richer benefits for all—than anyone could previously have imagined.

The popularity of the new video medium greatly increased employment, leading to the merger of the Screen Directors Guild (SDG) with the New York-based Radio & Television Directors Guild (RTDG) in 1960. It unified bargaining power under one roof, and brought together in a single union all directors of audiovisual content and the teams that support them. In addition, the merger made the DGA unique among entertainment craft unions for uniting East and West, thus covering all areas of technology and craft—features, television, news, and sports.

"I remember it as a very exciting time," said former DGA president and RTDG member Gil Cates. "And the potential we all felt at the time of the merger has been more than realized. As a unified guild representing all directors, we accomplished things that we never would have been able to separately. And the bottom line is directors have gained more creative rights and economic power from a stronger guild."

And yet these advantages might never have been won had it not been for the dedicated efforts of farsighted members at a time when expanding the Guild to include television directors was a daunting proposition, fraught with risk. More than 10 years of struggle and patient strategizing preceded the merger in 1960 that finally united film and TV directors nationwide in a single, prosperous guild.

At the outset, television was a live broadcast medium—a post-war outgrowth, it seemed, of the thriving radio industry that until then provided the nation's home entertainment. TV was initially touted as "radio with pictures," and some of the earliest model sets looked the part—console radios with the addition of tiny screens and of course, picture tubes. Most of the programs were created in New York, so it isn't surprising that the first efforts to organize the new medium took place there, where the Radio Directors Guild was headquartered. That group already had contracts with ABC, CBS, and NBC—all of which began as radio networks. In 1948, the radio guild secured a contract with CBS that also covered TV directors, and thus, changed its name to the Radio & Television Directors Guild, or RTDG. Similar contracts with the other networks followed soon after.

LIKE-MINDED: When Michael Kane, president of the RTDG's Hollywood chapter; Tom

LIKE-MINDED: When Michael Kane, president of the RTDG's Hollywood chapter; Tom

Donovan, president of the New York Local; and George Sidney, president of the SDG,

finally sat down to talk, they realized there was a lot to gain from the merger.

(Credits: (left to right) Courtesy of Michael Kane; DGA Archives; Everett)

As early as 1947, the Screen Directors Guild in Los Angeles had established a committee to examine the new video medium and consider how SDG members could become involved. In the late 1940s, TV stations such as KTLA, KTTV, and KECA (later KABC) began springing up in Hollywood. Programs such as The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, a popular radio show produced in Hollywood, would soon switch mediums and become nationwide television hits.

At around the same time, TV production, previously confined to New York and Los Angeles, spread to other major cities as newly licensed stations produced their own local news, variety, and children's shows—all of which required directors.

The SDG in Los Angeles began holding forums to educate its members about the technical aspects of the new medium and aid in their professional development, frequently bringing in executives and leaders in the field.

It also sought to promote the employment of members. In a letter sent to television producers dated Dec. 1, 1948, Guild President George Marshall assured them that SDG members were "anxious to participate in the future of television as it broadens its sphere of activity," and pointed out that prominent members such as John Ford, Cecil B. DeMille, and Hal Roach had launched production shingles devoted to TV. Marshall went on to say that for "production of high-quality films commensurate with the demands and requirements of the television industry, Hollywood is the logical center," thanks to its wealth of "equipment, technical know-how, experience, ingenuity, and creative ability."

This, of course, is not how things were seen in the East, where the theater-trained directors of live television, eventually dubbed "the New York style," saw their city as the natural center for all things television.

Nonetheless, on March 19, 1950, the SDG, under Marshall's leadership, boldly announced its intention to take jurisdiction over all directors and assistant directors working in television, citing "rapidly increasing employment of members in the preparation of film material for video screens."

Indeed, throughout the 1950s, work in the growing television field would prove to be plentiful. By 1956, nearly 35 million families, or 71 percent of all Americans, had purchased TV sets. The era of live, hour-long anthology drama series is remembered as the medium's golden age. By the end of the decade, many of the television directors in Hollywood had joined the SDG, either because they had begun to make movies, or because they were directing films for television.

To the forward-thinking Guild leadership, it was clear that in order to increase clout, bargaining strength, and revenue streams for the benefit of all directors, it was essential to bring practitioners of both mediums, regardless of location, together in one union.

But despite regular overtures emanating from West to East, members of the New York-based RTDG were resistant to the idea, and it was apparent that any proposal for a merger would face quite a few obstacles.

For one thing, each side was distrustful of the other's motives. "We thought New York was the center of the world," remembers Cates, then a self-described "scruffy" 26-year-old television director. "They were two different cultures. The East was made up of television people, many of whom had come from the theater, and the West was made up of moviemakers."

Hollywood was still the center of the film world, and given the comparative fame and wealth of the big screen directors, who counted among them legends such as DeMille, Ford, and Capra, the Manhattan-based practitioners of live television feared that rather than gaining clout in such a merger, they'd lose influence and be essentially swallowed up.

"It was silly, in retrospect, but that's what we thought," says Cates.

"They felt, truly, they were a weaker group. They didn't want to be swallowed up," says John Rich, who had started his career as a member of the RTDG, but later joined the SDG, where he became a board member for some 50 years. But the SDG, he recalls, "had no intention of swallowing anybody. We wanted the friendly merger, so that we would have directors directing actors and stories—rather than cameras." To have the two guilds divided on the basis of technology, he said, "would be a disaster."

PRESIDENTIAL SEALS: Television directors from the East Coast eventually became

PRESIDENTIAL SEALS: Television directors from the East Coast eventually became

presidents of the merged Guild. (left to right) Delbert Mann became president in

1967; George Schaefer in 1979; Gil Cates in 1983; and Jack Shea in 1997.

(Credits: (left to right) Photofest, Photofest, Everett, Photofest)

Cates says the east coasters saw the potential for video to become ubiquitous. At the same time, they were growing uneasy about maintaining a division between live shows and filmmaking based on guild affiliation. "We did feel that our technology was ultimately going to overwhelm film. Even though we couldn't imagine then what has taken place since, there was the instinct that at the end of the day, those of us on the East Coast were really going to be making television using our technology."

Other members had also begun viewing the gulf between the two guilds as counterproductive. Many television directors belonged to both organizations and found themselves paying two sets of dues, while production companies held the advantage of being able to negotiate two different contracts. And if a director who'd made a name in television wished to parlay that into film opportunities—as Delbert Mann did when the success of the teleplay Marty, which he directed for Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse in New York, leading to his opportunity to also direct the 1955 feature film—he had to apply for membership in the Screen Directors Guild. This was seen as an impediment to career fluidity. Like-minded members of both organizations began meeting to quietly lay the groundwork for a possible merger.

"I favored the idea," says Michael Kane, then-president of the RTDG's Hollywood chapter, and for 17 years the director of Art Linkletter's House Party on CBS. "It seemed to me there was no point in having two guilds—directors were directors." As talk of a merger started to percolate, Kane said he had lunch with TV colleagues John Rich and Jack Shea, members of the rival SDG, and told them, "We've got to make this happen."

But mutual suspicion still ran high—to the point that informal meetings to merely discuss the topic were held off the beaten path—at coffee shops like Ships in Westwood, rather than at industry watering holes like Chasen's. These tensions, however, subsequently began to ease.

George Sidney, who was president of the SDG for much of the '50s and '60s, recalled: "Finally, when we met with them, sat with them, and drank with them, we found out they weren't so terrible." He added, half-jokingly, "We both had something in common—we all hated the producers."

Shea, who at the time was directing Bob Hope comedy specials, remembered: "A large group of us had moved to L.A. and were working in TV, and we were switching back and forth between tape and film in different guilds. We realized that two unions competing with each other would only hurt themselves. So we actively encouraged the unions to join together."

Soon after that, Kane ran for international president—the RTDG's top office—on a merger platform, and was elected. Even so, he said in a recent interview that factions of the RTDG continued to offer considerable resistance. "The guys on the East Coast were still not too sure about this merger idea," he said. "During a board meeting, I remember saying to them, 'If you guys haven't got enough courage and self-esteem to be a part of this, you're making a big mistake.'"

The campaign to convince the East Coast holdouts required a persuasive personality, someone whose charisma and fame would disarm potential adversaries and draw them to the table. Past president Frank Capra, who had been so effective in getting the major studios to recognize the SDG in 1939, was pressed back into service in May 1951 and sent out to New York. But his charm, apparently, was not infallible.

Tom Donovan, a director of live shows such as Westinghouse Studio One in Hollywood and The United States Steel Hour, was president of the New York Local of the RTDG at the time. "One night," he recalls, "I received a telephone call at home and it was the great Frank Capra, saying, 'I'm at the 21 Club with some friends, fellows named Joe Youngerman and George Sidney,' and he named a couple of other pre-eminent directors. I was very nervous. He said, 'We'd like you and your wife to join us. We're talking about the possibility of the radio and television people and the movie people all becoming one.'

"I almost panicked," says Donovan. "Because at the time, we in the RTDG thought that if this were to happen, this big prestigious organization, the Screen Directors Guild, would swallow us up in one mouthful. So I declined. I thanked Mr. Capra for the invitation, but I said that I was busy. Many times after that, Capra referred to me as 'the anti-social director from New York.'

Still, after that phone call, Donovan recognized that the writing was on the wall. He and RTDG member Jack Sughrue went out to Los Angeles, to a meeting at the Roosevelt Hotel on Hollywood Boulevard. "We met with Jack Shea, Mike Kane, and Stu Phelps—western members of the RTDG—and it became very clear to us that the merger was in the best interests of the RTDG," says Donovan. "I have to tell you that I signed the last RTDG check at the time of the merger, and the sum of our total account was $50, so clearly the merger was a good idea."

But there was more drama to come, even as guild officers from Chicago and New York converged on L.A. to formalize the matter. "Everyone was out there for what we called 'the day of merger,' and there was still a group that was reluctant to give up power," Kane recalls. "I got a message through channels that if I didn't give the vice presidency [of the merged guilds] to Jack Sughrue, who was the New York president of the RTDG, they would call off the merger and go home. Joe Youngerman had to figure out how to make it work. It was a name and numbers game. So he called me the executive vice president, and Jack the vice president. And at that point Frank Capra and I shook hands publicly, and agreed to the merger."

The entire RTDG voted on the matter soon after that. The outcome was 555 members in favor, 77 against. At the SDG, the vote yielded a similar mandate from the vast majority: 666 in favor, 62 against.

On Dec. 7, 1959, it was announced in the Hollywood trade papers that henceforth, the two guilds would be merged into a single organization known as Directors Guild of America, Inc., made up of 2,068 directors, assistant directors, associate directors, stage managers, and program assistants. The newly christened DGA would handle contracts with CBS, NBC, and ABC, as well as with 361 film-producing companies. All this became official on Jan. 1, 1960.

There was good reason to celebrate. The combined Guild had a net worth exceeding $1 million, and there was great excitement over its expanding prospects. Capra was named president; Kane, executive vice president; and Sughrue, 1st vice president. "Growth is the bellwether of any organization, and our Directors Guild knew it had to grow," said Sidney.

But like many a marriage, this union of newlyweds rather quickly hit the rocks. The unease of East Coast officers over what they perceived as their diminished influence—exacerbated by a Guild practice of holding national board meetings in Los Angeles—resurfaced in a way that quickly became explosive.

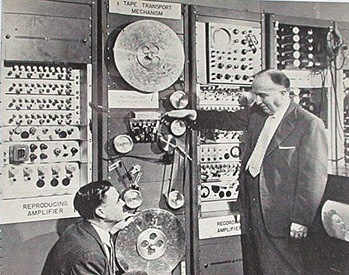

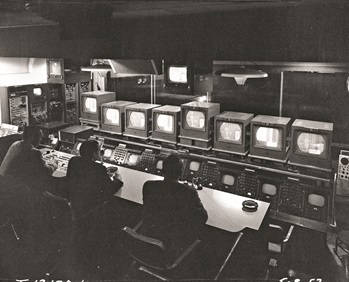

(Credit: Courtesy of Lyle Hoover & www.oldradio.com)

(Credit: Courtesy of Lyle Hoover & www.oldradio.com)

NEW TIMES: (top) NBC founder David Sarnoff demonstrates an early prototype of

a tape machine in 1953, which would become practical in 1956

when Ampex

developed a smaller format. The radical change in the standard method for

broadcasting live shows (bottom) was one of the things that made the

merger of New York and L.A. Guilds logical. (Credit: CBS/Landov)

A 1962 letter to the western directors, authored originally by Ted Corday and then modified and approved by a faction of the Eastern Regional Board, essentially proposed a rewriting of the Guild's constitution from top to bottom that would remodel it into more of a straight union format, rather than the guild format it was founded on. It also proposed the creation of a new structure in which equally powerful sub-boards on each coast would report to a national board that held reduced influence. The letter was signed by Corday, William Greif, and Bette Chichon, among several others.

"It was like dropping a bomb in the midst of the old guard," remembers George Schaefer, who was then-president of the Eastern Regional Board, but had been unable, due to his work schedule, to attend the meeting from which the letter was issued: "The western directors read it and blew their stacks, because it was just full of things they thought were exactly the opposite of what the Guild was intending."

In his own letter to the membership, Schaefer regretfully reported that "a small but determined group sincerely believes that the merger…as previously agreed to was a mistake, and that a return to local operation is best for the members in the East."

The proposals had so upset the Guild's West Coast leadership that it was seriously inclined to agree. At the next National Board meeting, Capra told the eastern members, "We made a mistake. We don't want you in our Guild."

"They put their foot down and said 'no way,' and said they would prefer to see the organization dissolve than to have it go on that way," said Ernest Ricca, who at that time had been newly appointed eastern executive secretary. But as talk of a split escalated, cooler heads determined that there was far too much at stake to allow for a catastrophic regression.

A solution, it seemed, called for some deep-think organizational restructuring and diplomatic finesse. As Ricca recalled it, some "very statesman-like people"—Schaefer, Fielder Cook, Franklin J. Schaffner, and Tom Donovan—formed a committee chaired by Donovan that worked out "a fair and equitable kind of constitutional approach."

This committee—in a plan it characterized as "drastic," but "for the benefit of all"—proposed the elimination of the western and eastern regional boards, a consolidation of power in the National Board, in which the East Coast would be fully represented, and the creation of councils organized by job categories—directors, assistant directors, stage managers, and so on—rather than by region. "That eased much of the East-West friction and in many ways, kept the newly merged Guild from splitting apart," Schaefer later recalled.

The period that was later referred to as "the time of the trouble" settled down then. "What resulted from that was a much smoother running of the organization," said Ricca, who stayed on as eastern executive secretary for the next 18 years. "The organization recovered really fast."

Indeed, members from the East Coast, the RTDG, and television became leaders of the national guild, beginning with Delbert Mann, elected DGA president in 1967; George Schaefer, who ascended to the presidency in 1979; Gil Cates, who took office in 1983; and Jack Shea in 1997.

Without a doubt, pay scales and working conditions for television members improved slowly but significantly after the merger. Equally important, the DGA grew into a unified and respected force in the industry.

Still ahead was the all-important fight for the basic Bill of Creative Rights that was established in 1964, and the era of advances in creative rights that followed. But by 1962, the members who established—and saved—the merged Directors Guild of America had proven that nothing succeeds like an idea whose time has come.