BY JAMES ULMER

BEFORE THE STORM: As president, George Stevens (behind the desk)

BEFORE THE STORM: As president, George Stevens (behind the desk)

presided over a meeting in January 1949, but the real control of the

Guild resided with the board, a balance of power that would change

as a result of the October 1950 meeting. (Credit: DGA Archives)

It was, by many accounts, the darkest night in the Directors Guild's 75-year history.

On Oct. 22, 1950, more than 300 Guild members gathered for seven hours to fend off a political crisis that threatened to destroy their governing body, turn union brother against brother, and undermine the Guild's own long-term survival.

The setting was Hollywood's anti-Communist purge, when the winds of "witch hunts" and "red-baitings" were catching the industry in the crosscurrents of creeping panic and intolerance.

The plot turned on a mandatory loyalty oath: Would the Screen Directors Guild, as it was then called, risk a rupture by voting to adopt one for its members? More to the point, would it sack its own president as a necessary sacrifice to vanquish the Red Scare?

Among the cast of characters who had staked their reputations, even their careers, on the outcome that night was a marquee of cinematic giants: Cecil B. DeMille, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, John Ford, John Huston, Frank Capra, Fred Zinnemann, William Wyler, Rouben Mamoulian. And the unsung hero of it all—George Stevens.

In a bizarre role switch, these directors had arrived at the meeting to direct themselves out of a scenario that was as dramatic as any they had set before a camera. First, the backstory.

By 1950, fear of an impending, far-reaching industry blacklist was palpable. Washington's own posse of anti-Communist bloodhounds, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), had begun in 1945 to hunt down and punish anyone who bore even a suspicion of being a Communist sympathizer. Hungry to feed off the headlines their Hollywood housecleaning would generate for their cause, Washington's witch hunters had already interrogated and locked up the "Unfriendly Ten"—a band of writers, directors, and producers who had refused to testify to the HUAC whether or not they were Communists. In Hollywood, many working professionals were bracing for another venomous round of red-baiting by the demagogic Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his Capitol Hill gang. Overseas, the Korean War further fueled the climate of tension and uncertainty across the country.

As Huston summed it up: "It was not a very good time for the Guild, or for anything else in this country."

Thanks to the Red Scare, the Guild's board of directors was a house deeply divided. On one side was the faction of the SDG's most famous and powerful member, the arch-conservative Cecil B. DeMille, who had railed against "unionism" at the Guild's first organizational meeting 14 years earlier. The revered 69-year-old director was an unwavering ideologue and was also the Guild's self-appointed watchdog. He had gained control of the organization through seniority and by maneuvering to install equally right-wing elders onto the board. DeMille also headed the DeMille Foundation for Political Freedom, which was dedicated to compiling files on the leftist affiliations of all screen directors—files that would ultimately be spoon-fed to the HUAC.

On the other side were the supporters of the Guild's brilliant and successful young president, the 41-year-old Mankiewicz. A Republican, "Mank" had just won a DGA Award and two Oscars for writing and directing A Letter to Three Wives, and was about to win two more for his recently wrapped picture, All About Eve. He was nobody's fool, but a political novice compared with DeMille.

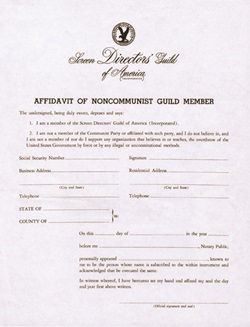

DeMille and his backers on the Guild's board—namely 1st Vice President Albert S. Rogell and George Marshall—had concocted a patriotic plan for the Guild to become the first Hollywood union to institute a membership loyalty oath. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 had already mandated that all union officers sign anti-Communist affidavits, which the Guild's board members, as well as President Mankiewicz, had certainly done. But union members themselves remained exempt from any oath. And that was a situation which DeMille and his supporters intended to change.

The single obstacle in their path was the Guild's president, who had publicly rebuffed the idea of a mandatory membership oath. If their scheme were to succeed, they would have to push it through behind Mankiewicz's back while the director was away on a two-month European vacation after the completion of Eve.

(Credit: AMPAS)

(Credit: AMPAS)

On Aug. 18, when Mankiewicz and his wife were sailing from France and couldn't easily be reached by phone, DeMille and his faction decided to strike.

It may be helpful here to consider how the Guild's own internal genetics could, at that time, allow such an in-house conspiracy to grow. The real power of the SDG then resided not with its president, nor with its membership, but with its self-perpetuating 15-member board. DeMille had endorsed Mankiewicz's installation as president in early 1950, shrewdly figuring that the young director's Oscar-laden credentials, along with his well-known distaste for political activism, would stifle any risk of troublemaking and render him malleable to his guidance.

As Mankiewicz put it in a filmed interview years later, "It became clear that I was the front that Mr. DeMille needed and wanted…. What Cecil really wanted was to become the commissar of loyalty of the entertainment business."

To Mankiewicz, the board's all-encompassing power was a structural weakness that became a key enabler in the blacklist drama. "The board literally ran the Guild," he noted. "[It] was accountable to no one…and was as close to being a gentleman's club as is possible to have created…I had no power whatsoever." Essentially, he saw his presidency as a setup, a stage with a trapdoor operated by DeMille.

Meanwhile, on that day in August with Mankiewicz conveniently away at sea, DeMille called an emergency meeting of the board. According to Rogell, DeMille had already told a select group, including Capra, that he had received word from a very reliable source in Washington that McCarthy was going after Hollywood and had his sights set on the Directors Guild. So to presumably diffuse that, the purpose of the meeting was to draft a new bylaw making it mandatory that all current and prospective Guild members, and not just the board itself, sign a non-Communist loyalty oath.

Strategically, they mailed out numbered, open ballots, virtually assuring that the vast majority of the 618 recipients would be too fearful of identifying themselves as opponents not to vote "yes." Not surprisingly, the bylaw was passed by an over-whelming margin—547 to 14, with 57 unreturned. No one, it seemed, wanted the threat of a blacklist to jeopardize his career, since Guild rules mandated that the names of those refusing to sign be delivered to the studios.

HEAVYWEIGHTS: Cecil B. DeMille (left) spearheaded an attempt to recall Joseph L.

HEAVYWEIGHTS: Cecil B. DeMille (left) spearheaded an attempt to recall Joseph L.

Mankiewicz (right) as president of the Guild in October 1950. At issue was

the adoption of a loyalty oath for all members. (Credits: Everett; Kobal)

Unaware of DeMille's machinations, on Aug. 23 Mankiewicz sailed into New York City from his vacation and found himself greeted at the dock by a hoard of 50 reporters. What was his explanation, they wanted to know, for the Guild passing a compulsory loyalty oath? Stunned by the news, Mankiewicz returned to his hotel room to find it flooded with hundreds of letters, telegrams, and phone calls from Guild members. Nearly all protested what they saw as an attempt to railroad directors into signing an oath without calling a membership meeting to explain its reasons.

Mankiewicz immediately challenged both the legality and morality of such a move and called a board meeting for Sept. 5, 1950. At that meeting, Mankiewicz argued, as he recalled in a 1985 Guild interview, "You can't send out an open ballot which you're supposed to sign with your name on something that affects your conscience. And DeMille would say something like, 'Now is the time every American's got to stand up and be counted.' And I'd start to say, 'Well, yes, that's probably true but who appointed you to do the counting, Mr. DeMille?'"

Then the DeMille faction let loose the board's pretext for the vote: Since all Hollywood unions and guilds, they insisted, were inevitably going to adopt a compulsory membership oath, they wanted the SDG to be the union that led the way. "It is a wonderful thing, the Directors Guild leading the procession of planting the stars and stripes on [this industry]," DeMille proclaimed.

It was only the opening volley in DeMille's orchestrated anti- Communist campaign. First, the director screened several of Mankiewicz's movies to check for signs of Communist propaganda. When he found none, DeMille instructed Rogell to contact the press and openly accuse Variety of being "anti-American" for printing one of Mankiewicz's previous anti-oath statements.

DeMille and his supporters also protested Mankiewicz's use of the term "blacklist" in characterizing the Guild's new bylaws. While the Guild would indeed be obliged to include all non-signers of the oath as "members not in good standing" (a term usually assigned to members who hadn't paid their dues), the studios, they said, would still be free to hire and fire anyone they wanted.

But Mankiewicz wasn't buying that argument. "This guy's un-American but you can hire him—that's a blacklist," he protested at a heated board meeting on Oct. 9. Like Stevens, his only open ally on the board, Mankiewicz was deeply disturbed by the open balloting that had effectively scared up a victory for the DeMille faction. "I said, 'It seems to me that kind of thing only happens in Moscow,'" Mankiewicz later recalled. "And [DeMille] said, 'Well, maybe we need a little of that here.'"

While Mankiewicz made his argument against what he considered a de facto blacklist, "I looked right at Jack Ford when I said it and Ford jumped a foot," Mankiewicz recalled in an interview for the Guild's 50th anniversary. "He didn't want any part of a blacklist, which I'd hoped would be the case."

Although Mankiewicz had won the support of Ford and several board members, he was still outmaneuvered by DeMille's clan, and the board formally endorsed the bylaw with its "blacklist" provision.

That left Mankiewicz only one card to play. He insisted that, as president, he would call a general membership meeting to discuss the balloting. DeMille decried the idea, claiming it would only serve to air the Guild's "dirty laundry" in the papers. He agreed to allow a closed vote on the loyalty oath if Mankiewicz would call off the meeting and sign a statement of contrition stating that he was not against the oath and had acted in haste. Mankiewicz told him, "Mr. DeMille, I hate being a little rude but you can stuff your act of contrition. I don't sign an act of contrition to anyone."

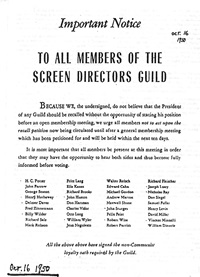

STOP THE PRESSES: Twenty-five Guild members signed a petition calling for a

STOP THE PRESSES: Twenty-five Guild members signed a petition calling for a

general meeting to head off Mankiewicz's impeachment and signed a letter

urging members to attend the meeting. (Credit: AMPAS)

Indeed, the media were having a field day with the story with Variety reporting that "Mankiewicz Will Not Sign Oath." Gossip columnist Hedda Hopper wrote that she supported the industrywide oath and insisted "those who aren't loyal should be put in concentration camps before it's too late." Hearst Corporation's Louella Parsons had a personal ax to grind with both Mankiewicz and his brother Herman, ever since the latter modeled his scabrous screenplay for Citizen Kane after her employer. Indeed, so much venom was hurled at Mankiewicz for refusing to support an industrywide oath that his own sons complained of being taunted as "Commies" by their grade school peers.

Meanwhile, DeMille and his cohorts were preparing to detonate their biggest land mine in their Hollywood anti-Communist crusade.

Two days after the Oct. 9 board meeting, DeMille convened a secret meeting of the anti-Mankiewicz supporters at his Paramount offices. Their plan? To oust their president by means of a cleverly orchestrated recall movement. With only one loyalist breaking rank—Capra walked out of the meeting in disgust, soon to resign from the board—the group voted to move ahead. But DeMille's "putsch in the night," as Huston dubbed it, would have to be engineered hurriedly and stealthily before Mankiewicz could have a chance to stop it—certainly before the membership meeting Sunday. And it would legally need the support of 60 percent of the Guild's membership, or 167 votes.

On Thursday, the Guild's executive secretary and DeMille's former assistant director, Vernon Keays, worked overtime with the Guild's staff to mimeograph the ballots on anonymous stationery. The entire text read as follows: "This is a ballot to recall Joe Mankiewicz. Sign here—Yes."

There wasn't a space for a "no" vote, and the ballots were numbered so that each voter's identity could be traced. The return address was the Guild's Hollywood office, a ruse leading most recipients to assume, mistakenly, that it was a matter of official board business.

To avoid sending ballots to possible Mankiewicz sympathizers who might alert him to the attempted coup, the Guild's address lists were carefully purged of 55 names before the envelopes were stuffed, addressed, and carted over to DeMille's office. There, under the cloak of night, they were hustled off to a cluster of messengers on motorcycles for delivery to members' homes across the city.

Over on the Fox lot, Mankiewicz was in a screening room when he received a phone call at 11 p.m. from his brother Herman, who had been tipped off to the nascent coup. "So what do you have in common with Andrew Johnson?" Herman blurted out, hardly waiting for a reply. "You're being impeached, my boy."

"It seems John Farrow had shown up at my brother's house," recalled Mankiewicz, "and Farrow had just thrown George Marshall out of his house because Marshall had arrived in a motorcycle sidecar carrying a scroll demanding my immediate impeachment because of my behavior towards the loyalty oath."

The next evening, while All About Eve and its own backstage shenanigans were drawing raves at its premiere in New York, Mankiewicz launched his counter-strike. He called a meeting of supporters in a back room at Chasen's restaurant, where Oscar winners Billy Wilder, Elia Kazan, Richard Brooks, Wyler, and Huston were among those in attendance.

Mankiewicz's lawyer, Martin Gang, started off by predicting that if the recall movement succeeded, Mankiewicz's filmmaking career would be ruined. He suggested two immediate actions: a legal injunction to stop the balloting, and a petition for a general membership meeting to inform everyone of Mankiewicz's side of the story.

John Ford confronted DeMille at the fateful meeting. (Credit: Photofest)

John Ford confronted DeMille at the fateful meeting. (Credit: Photofest)

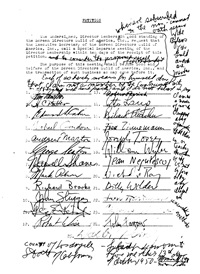

Huston immediately volunteered to sponsor the injunction. But it would take 25 signatures to call a meeting, and the group worked feverishly through the night to track down the necessary quorum, knowing full well any signatory would risk the wrath of DeMille. Nicholas Ray, Robert Wise, Vincente Minnelli, and Fritz Lang were among those affixing their names, and at 2 a.m. a limo was directed to Walter Reich's home to secure the 25th signature. The document was "our declaration of independence," Mankiewicz would say, later mailing out framed copies to the signers as a reminder of their courage.

"The purpose [of the petition] was not to say, 'I support Joe or I don't want Joe to be thrown out,' but to bring it all out in the open," explained Brooks in a 1985 interview. "Not somebody sending a telegram that arrives at your house signed by three or four of the most important names in our business so that you want to leave town because you don't know what to think."

But when a small delegation marched over to file the petition at the Guild's offices at 9 a.m. on Saturday (a normal workday for the Guild), they were shocked to find the offices closed. Stevens said he called the Guild office but the phone didn't answer. "Well, that put me to wondering," he said. Stevens then proceeded to launch his own investigation, questioning Guild employees, which he would later report on in a crucial testimony at the Sunday meeting. Keays later admitted to ordering the office shuttered in a move to sabotage the petition's chances. As Mankiewicz's forces raced to the phones to lobby members against signing their recall ballots, DeMille's faction fired up its final sally to justify the recall and squeeze out its quota of votes.

A four-page telegram was sent to all 278 senior members alleging that Mankiewicz had "repudiated the democratic vote of its membership," "pitted himself against its board of directors," and had made "untrue and incendiary" accusations of a "blacklist."

DeMille's forces, however, couldn't stop the Mankiewicz petition, which was served Monday morning. Now the board was obliged to hold an assembly of the membership, which was called for Sunday evening, Oct. 22, 1950.

As Huston put it, "The fat was on the fire."

Although all of the story's major players have now passed on, their voices can be heard in dozens of books, articles, and taped and filmed remembrances of that tumultuous night 60 years ago. For more than seven hours, a collision of raw nerves and bruised loyalties played out in the packed room as members cheered, booed, clapped and catcalled their response like a scene from a DeMille adventure epic.

Far beyond the political repercussions, the issue to be tested for the Guild was this: Could ideology destroy fraternity?

"It was the most incredible…and emotional meeting I have ever experienced, and ever will," Mankiewicz told George Stevens Jr. in a 1984 film the latter made about his father, George Stevens: A Filmmaker's Journey. A chapter in the biography Pictures Will Talk: The Life and Films of Joseph L. Mankiewicz, dubs the meeting "The Night They Drove Old C.B. Down." To Stevens Jr., who was 18 at the time his father played a leading role in the drama, it was simply "the night the Guild rallied to save its soul."

"We had booked a room in the Beverly Hills Hotel, and Huston and Kazan and George Seaton worked over my opening speech as if I was submitting a screenplay to these three directors," said Mankiewicz. Things were getting tense and finally at 8 o'clock, as Mankiewicz recalled, Kazan came up to him and said, "'Okay, kid, this is as far as I go,' and he gave me a kiss and walked away. I said, 'Why, Kaz? You're a fighter, I need you.' He said, 'DeMille is waiting for me because he knows I'm going to Washington pretty soon to testify. He will use me to kill you.'"

UNSUNG HERO: Sensing wrongdoing, George Stevens did his own investigation

UNSUNG HERO: Sensing wrongdoing, George Stevens did his own investigation

into the impeachment proceedings and reported his findings at the meeting,

saving Mankiewicz's presidency and perhaps the Guild. (Credit: Kobal)

In the packed Crystal Room of the Beverly Hills Hotel, the crowd was primed for a fight. The board of directors and President Mankiewicz held court on the dais, where DeMille, ever the showman, had directed a special pink spotlight be installed to bathe his baldpate.

Mankiewicz opened the proceedings with a straightforward synopsis of the events leading up to that night. DeMille took the floor and offered what seemed an olive branch: He would be willing to burn, uncounted, all the recall ballots. But he would not back down on the loyalty oath.

Then DeMille made his first strategic blunder. Eager to show the foreign influences at work in the Guild, he read off a list of presumed "Red front" organizations to which the 25 signatories belonged, suggesting that if Mankiewicz remained as president, his left-wing supporters would take over the Guild.

"They had a dossier on everybody who signed that statement," recalled Richard Brooks. "By dossier I mean they knew who he was, where he was born, what they did."

That triggered a torrent of boos and catcalls from the packed hall, leaving DeMille clearly shaken as he sat down. "I resent paper-hat patriots who stand up and holler, 'I am an American' and contend that no one else is," exclaimed Don Hartman.

Some stammered with outrage as they stood up to speak. "I resent beyond belief the things you said as you summarized the 25 men," said Delmer Daves. "I think it was disgraceful…this…disunity that has been fostered upon us."

Others, like Rouben Mamoulian, were nearly in tears. The Russian-born director rose to make what Brooks remembered as the most "heart-wrenching" address of the night.

"I have an accent," Mamoulian offered painfully, sharing that for the first time in his American life he had become afraid of having one (a fear echoed later that evening by Fritz Lang). He, too, deplored the way members needed to trace their heritage to prove their Americanism. "I feel I have more reason to stand on my being a good American because I chose it. I wanted to become an American."

Huston was "trembling with anger," according to one report, when he demanded of DeMille: "In your tabulation of the 25 men…how many were in uniform when you were wrapping yourself in the flag?"

Hartman demanded that DeMille withdraw his charges and insinuations against the 25, but DeMille would not be cowed, insisting all his information was already a matter of record on Capitol Hill. He then proceeded to read off names of Guild members he judged most vulnerable to communism. Worse, he pronounced the names of the émigré directors with a Jewish (some would call it anti-Semitic) accent: "Veely Vyler," for example, and "Fred Tsinnemann."

Wyler, who was sitting in the front row because he had had an ear blown out in a bombing raid over Berlin during the war, could hardly contain his anger. "I am sick and tired of people…questioning my loyalty to my country," he exclaimed, noting he had signed a loyalty oath twice. "The next time I hear somebody do it, I am going to kick the hell out of him. I don't care how old he is or how big."

Turning to confront DeMille, Hartman delivered the evening's most audacious sally: "Mr. DeMille, I have charges against you…I accuse you of misconduct in the Guild, and I ask for your resignation." His words met with cheers. Though the motion was seconded, it would later be withdrawn in a bid for Guild unity.

As Stevens would later observe, many of the Guild's most respected men, including Wyler, Huston, Ford, and Anatole Litvak "had served in World War II and resented the fact that some of those that stayed home, for whatever reasons—Ronald Reagan, John Wayne, Adolphe Menjou, and DeMille among them—had now become the judges of who were patriots or not."

But it was Stevens himself—the dignified and much-revered director who had served three times as Guild president—who delivered what Mankiewicz termed the coup de grâce of the evening. Seated at a little table crowned by his bulging, red, loose-leaf notebook, he proceeded to read from an exhaustive report he had compiled from Guild staff interviews, unloading his case against DeMille and his cohorts' "illegal takeover" of the Guild.

"George waited until exactly the perfect moment of timing," recalled Mankiewicz in a 1985 interview. "And then he read an account of the detective work he had done."

"It was rigged," Stevens said of the recall. "It was organized…and if there hadn't been a slipup somewhere … Mr. Mankiewicz would have been out. He would just have been smeared and out … in 36 hours, if you please." The Guild office staff, he added, "said they couldn't sleep at night with a conspiracy like this going on."

Stevens then stunned the audience by resigning from the board of directors, "because [of those] who are trying to split up this Guild." It was a performance, Mankiewicz later remembered, "worthy of Clarence Darrow." That night, Stevens concluded it to thunderous applause.

"George did the most incredible job of interrogation and pinning people down," Mankiewicz said. "He had been to the Guild office and taken testimony from secretaries and everybody that the membership lists that had disappeared were in Mr. DeMille's office, and Guild envelopes had been franked out to DeMille's office, too…. The work that George did of exposing what this was and the fact that the Guild had been run by DeMille for the benefit of a small group of men was absolutely perfect. There was no need for the meeting to continue except somebody had to bring it to an end, and of course that person was sitting right in the middle of the room."

Sitting quietly for the past five hours in the center of the dais, sporting his trademark tennis shoes and pipe and chewing on a handkerchief, was John Ford. One of the Guild's founders, Ford was idolized by its members. Mankiewicz knew that whichever way Ford swayed in the controversy, the membership would doubtless follow—and with them, Mankiewicz's fate.

Finally, after midnight, Ford raised his hand with a director's sense of drama and timing.

"My name is John Ford. I am a director of Westerns…. I have been sick and tired and ashamed of this whole goddamn thing—I don't care which side it is," Ford told the crowd. "If they intend to break up the Guild, they've pretty well done it tonight…. I don't think we should [be] putting out derogatory information about a director, whether he is a Communist, beats his mother-in-law, or beats dogs. That is not our purpose."

Playing the conciliator, he added, "I don't agree with C.B. DeMille. I admire him. I don't like him, but I admire him....You know when you get the two blackest Republicans I know, Joseph Mankiewicz and C.B. DeMille, and they start a fight over communism, it is getting laughable to me."

The Guild, Ford said, was in crisis and needed to clean house. Then he dropped his bombshell: "There is only one alternative, and that is for the board of directors to resign and elect a new board." His words were greeted with a roar of applause and cheers.

Ford's proposal offered a way out, and the bleary-eyed members, some of whom were due on their sets in only a few hours, voted on the motion by ballot. The announcement by Mankiewicz of its passage earned the night's final ovation, whereupon each of the board members rose to offer his resignation. The image of a battered, humiliated DeMille descending from the podium and withdrawing defiantly to the back of the hall was a memory few would forget.

The only piece of business left was to approve a five-man independent committee to investigate the entire recall affair, and to pass another motion praising the 25 petition signers who had called the meeting. Then the emotionally wrung membership adjourned. It was 2:20 a.m.

(Credit: AMPAS)

(Credit: AMPAS)

Looking back, it might seem that not much of any real consequence was actually accomplished that night. The Guild, after all, still instituted a loyalty oath for its members, which remained on the books until the Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling in 1966. In the coming days, Ford backpedaled and wrote a conciliatory letter to DeMille, hailing him for his "courage…and magnificent performance…so far above that goddam pack of rats." Nonetheless, DeMille found his influence in the Guild permanently diminished.

As for Mankiewicz, only four days after the meeting he penned a letter to the full membership asking them to sign the loyalty oath after all. He never really explained his capitulation, but it may have been to mollify Capra, who believed it was necessary to satisfy doubts about members' patriotism. To some it suggested he cared less about that oath itself than the undemocratic way the board pushed it through.

It is certainly true that what would later be considered one of the Guild's most climactic meetings had little political impact in stemming the tide of the Communist witch hunt in Hollywood. Few, if any, Hollywood institutions acquitted themselves in this unfortunate chapter. Indeed, some observers regard the meeting as little more than political posturing—on both sides of the aisle.

Ultimately, this episode resonated less politically than it did on the future of Guild, starting the day after the meeting. "I wound up the next morning with [control of] the Guild," said Mankiewicz. "And I didn't quite know how to go about being the Guild by myself, so I got King Vidor and George Stevens and a few other past presidents and we sort of put things together again and hired Joe Youngerman [as executive secretary]. We had some proper bylaws written which made the membership the people who would control the Guild."

When Mankiewicz was nominated for another term as president in 1951 (by none other than DeMille) he declined, noting that he was planning to move back East. He was replaced by the centrist George Sidney. "The important thing was bringing this group of disassociated men and great talents together to form one organization, and that's where we started," Sidney said in a Guild interview some years later. "I think we have managed to do this and solidified our organization."

And as if to answer Mankiewicz's expressed concerns, the board was now empowered to represent the goals of members, and not merely its own self-interest. Personal political agendas would no longer determine the workings of the Guild at the expense of representing and protecting the collective rights of directors to pursue their craft.

"Since then," said Huston, reflecting back on those events on the occasion of the Guild's 50th anniversary, "the Guild has straightened itself up and come out of the restrictions that it endured. It learned its lesson."

It's no wonder, then, that many directors left the meeting that night with a renewed sense of purpose. Among them was Stevens, whose extraordinary presentation, many believed, had persuaded Ford and the membership to bury the recall. Experiencing a mixture of exhaustion and exhilaration, he was unable to sleep. He hopped into his car with his son George and drove 50 miles up the coast to Ventura and back, not returning until 4 in the morning. Like Ford, he had lamented that the Guild's obsession with fighting communism had trumped its commitment to making movies. The civil war of director against director had ended, and now the Guild was back on track.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Winter 2006/2007 DGA Quarterly from which this is adapted.