BY STEVE POND

FIRST TIMERS: President George Marshall (center) gives out quarterly

FIRST TIMERS: President George Marshall (center) gives out quarterly

awards to (from left) George Stevens, Darryl F. Zanuck (accepting for

Howard Hawks), Fred Zinnemann, and Joseph Mankiewicz, who also

won the first annual award for directing. (Credit: DGA Archives)

There was no red carpet. No movie-star presenters. No paparazzi, no questions about "who are you wearing," no pundits talking about what it all means for the Oscars.

When the Screen Directors Guild presented its first award for the year's best directorial achievement, the Hollywood awards landscape was very different. The Golden Globes had taken place five times, without drawing much attention. None of the major Hollywood guilds had begun to hand out their own prizes. The only real game in town, in many ways, was the Academy Awards, which had existed for almost 20 years but wouldn't be televised for four more.

But in 1948—the same year the British Academy Film Awards was established, and a year before the Emmy Awards would have its inaugural ceremony—the Screen Directors Guild made a declaration of independence from the Academy. "It isn't that we're dissatisfied with the Academy Awards," SDG President George Marshall told the United Press at the time. "We just want awards of our own judged on technique only. The Academy Awards involved personalities and publicity." Besides, he added, "At the Academy Awards the public's interested only in the stars. They don't give a damn about directors."

The result was four quarterly awards, culminating in a low-key dinner at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel that took place before the SDG's annual business meeting on May 22, 1949. At that dinner, the quarterly awards went to Joseph Mankiewicz for A Letter to Three Wives, Fred Zinnemann for The Search, Howard Hawks for Red River, and Anatole Litvak for The Snake Pit. Mankiewicz was also given the first Annual Award for Directing for 1948-49. "The highest award a man can get," said Mankiewicz that night, "is to be selected by his fellow craftsmen."

But before these men could take the stage, the Screen Directors Guild had to lay the groundwork. At the time, tension still existed between the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Guilds, which was largely run by the studio chiefs. A decade earlier, the fledgling guilds had organized a boycott that damaged the Oscars' authority, asking their members not to attend the ceremony in 1936, limiting the turnout of actors, writers, and directors. But even in the aftermath, the guilds did little to challenge the Academy's authority. When the Screen Directors Guild, Screen Actors Guild, and Screen Writers Guild collaborated on the first "Tri-Guild Ball" in 1938, at a time when all three were fighting for recognition from the Hollywood studios, the program for that event, after introductory remarks from the three guild presidents, merely singled out the members of each guild who won Oscars that year.

Finally, at a meeting in June 1948, according to minutes in the Directors Guild archives, discussion took place for "the mechanics of an award setup," with the proviso "that it might be advisable to make one award as a trial balloon to learn what attention it would command." The SDG's publicist, John "Scoop" Conlon, reported at the meeting that he'd discussed the idea of an award with New York magazine and newspaper editors, all of whom were "very interested." The Academy wasn't as enthusiastic, and tried to persuade the SDG to take over the nominating process for the Oscar directing award. The directors declined. (The Writers Guild inaugurated its honors the same year as the directors; the Screen Actors Guild wouldn't do so for four more decades.)

The directors' announcement hit the trades in August 1948. "Effective from last May 1 the Screen Directors Guild is establishing 'family affair' awards to be presented quarterly for the best directed picture, and annually for the outstanding directorial achievement of the year," wrote Variety under the banner headline announcing, "SDG Gives Own Awards."

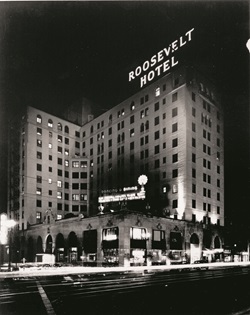

The ceremony was held at the Roosevelt Hotel on

The ceremony was held at the Roosevelt Hotel on

May 22, 1949. (Credit: Hollywood Photographs)

The "family affair" quote had come from Marshall. "This is to be a family affair, free from prejudice and unhampered by outside influence," he said to Guild members. "You yourselves are to be the judges and the jury because no person is better qualified to pass upon the creative ability of the director than the directors themselves." The purpose of the awards, he added, "is to give credit where credit is due and to enhance the position of the director in the eyes of the press, the public, and the industry."

An Awards Committee was created, consisting of George Sidney, Frank Capra, Delmer Daves, John Ford, Bruce Humberstone, Irving Pichel, Norman Taurog, and Marshall—but the committee's plan to begin handing out quarterly awards for the period from May 1 through July 31, 1948, drew some criticism. George Stevens wanted the 1948 films that had been released before May 1 to have a chance at recognition because, as the minutes of a board meeting noted, "In the opinion of Mr. Stevens, the effects of the Directors' Award would influence the annual Academy Award and he felt that pictures released up to May 1 should be given the same consideration as those released during the balance of the fiscal year." A decision was made, though, to go ahead with the quarterly awards beginning May 1. Minutes of the meeting reported that, "It seemed unfortunate that anyone should suffer but the fact remained that the Awards had to be started at some time to get them under way and no matter when this was done some director would feel that he had been slighted by the exclusion of his picture."

At the same meeting, the issue of campaigning and trade ads first surfaced. Conlon announced that the trade paper The Hollywood Reporter was offering a special issue to go with the annual directorial award, "in much the same manner as the one now put out at the time of the Academy Awards." The consensus, however, was that such an arrangement would show favoritism to one paper over others, "and might open the way to high-pressure advertising to which the average director objected."

Going ahead with its plan, the SDG gave its first quarterly award to Zinnemann. A spokesperson told The New York Times that about 200 of the guild's 287 members cast ballots. In November, the second award went to Hawks' Western Red River. "We are more than gratified with this selection," announced Marshall, "because it further proves that the directors are voting for the best job of directing no matter what type of picture." One minor controversy surfaced when it was disclosed that Laurence Olivier's version of Hamlet was left off the ballot through an oversight on the part of its distributor, Universal International.

But the trade papers paid scant attention to Hawks' award: In Variety, it was given two paragraphs at the bottom of Page 2, sandwiched between a Samuel French ad and a story about the Academy getting a 1911 camera for its archives. The snub became a major topic of conversation at the next board meeting, where Conlon pointed out that because the news was furnished to the local newspapers, which were out at 7 p.m. the night of the awards, the two main trade papers refused to feature it in their morning editions. The consensus of opinion on the board, though, was that "the quarterly directorial award was worthy of individual prominence in the local trade papers irrespective of other releases." The board also discussed issuing an edict prohibiting any director from taking out an ad in the trades, a tactic that was said to have worked to resolve previous disputes with the papers.

GOOD NEWS: A program for the growing event lists the

GOOD NEWS: A program for the growing event lists the

four quarterly award winners for 1954 (Kazan won the

annual award).

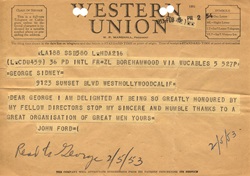

John Ford telegrammed President George Sidney

thanking the Guild for the annual award in 1953

for The Quiet Man. (Credits: DGA Archives)

After Litvak won the third quarterly prize and Mankiewicz the fourth, ballots were sent to all SDG members in early May with the names of the four quarterly winners. Out of the Guild's then 380 members, only 119 voted; Mankiewicz won with 37 votes, to 34 for Zinnemann. Hawks and Litvak tied with 24. So Mankiewicz won the Guild's first annual award and 10 months later he would become the first in a long line of SDG (and later DGA) winners who would go on to win the Academy Award for best director. The awards portion of the evening was broadcast on a local radio station, KLAC, with Marshall presiding.

The SDG prize was a 4½-inch medallion (the quarterly awards were smaller) designed by Daves. Those awards, and an honorary plaque for "outstanding service" to past president Stevens, were handed out at a dinner attended by 350 people, though Litvak and Hawks couldn't come. Immediately after the dinner and award presentation, the Guild convened its annual business meeting, where Mankiewicz won another vote: He was elected vice president of the SDG, while Marshall won re-election as president.

The award made the front page of Variety above the fold, but it wasn't big news everywhere: The New York Times gave it two paragraphs. Still, Mankiewicz told the United Press that the award meant more to him than an Oscar because "the movies are judged only for directing. It doesn't matter what studios or personalities are involved." (These lines were delivered, wrote the UP reporter, in a tone "more fluttery than the movie queens who cart home Oscars.")

The second SDG Awards, held on May 28, 1950, moved to the Beverly Hills Hotel and enlisted comedian George Jessel to host. Actors Ruth Roman, Mel Ferrer, and director/actor Ida Lupino were on hand to present the quarterly awards, while the final vote was handled differently: Members chose between the quarterly winners—Robert Rossen for All the King's Men, Mark Robson for Champion, Al Werker for Lost Boundaries, and Carol Reed for The Fallen Idol—with a floor vote that took place during the ceremony. Rossen won for a film that two months earlier had won the Academy Award for best picture—though the Los Angeles Times goofed in its coverage, saying that Rossen had won the best director Oscar. (Mankiewicz won for A Letter to Three Wives.)

Until then, SDG rules had stipulated that the final vote was made only by directors, but in the aftermath of the second ceremony, a recommendation was made and unanimously passed that assistant directors be allowed to vote as well. Three months later, another change added award medallions for the assistant directors to go along with the ones for directors.

Mankiewicz became the first two-time winner in 1951, when he picked up the third annual award for All About Eve. "If ever there was a time to quit, this is it," the director said in his acceptance speech. "This award will be comforting in the years and stinkers that lie ahead." (His competition: John Huston for The Asphalt Jungle, Billy Wilder for Sunset Boulevard, and Vincente Minnelli for Father's Little Dividend.) The ceremony was still part of the Guild's annual business meeting, but changes were afoot: The show, which was emceed by Paramount production chief Don Hartman, was broadcast for the second time on NBC, and included appearances by Barbara Stanwyck, Elizabeth Taylor, and Ava Gardner, among others.

Hartman, according to L.A. Daily News columnist Ezra Goodman, "revealed himself as quite a podium wit in his capacity as toastmaster," saying that the directors were "more than anyone else responsible for the making of good motion pictures," and then quipped, "If the Screen Writers Guild insists on my being toastmaster at their function, I'll say the same about the writers."

HONOREES: Al Werker (right) receives a Quarterly Award from

HONOREES: Al Werker (right) receives a Quarterly Award from

Albert Rogell and Joan Fontaine in 1950.

George Sidney presents the first two Lifetime Achievment Awards to Cecil B. DeMille (middle) and John Ford (bottom).

(Credits: Los Angeles Public Library)

By 1952, the awards were presented at a fancier dinner dance at the Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. Jane Powell sang "The Star-Spangled Banner," the David Rose Orchestra performed, and a local news report said the 800 guests included "toppers in the executive, producer, and directing fields, plus numerous stars and civic officials." Stevens won for A Place in the Sun over Alfred Hitchcock's Strangers on a Train and Minnelli for An American in Paris. (There were only three quarterly winners in order to move the show to a calendar-year format.)

By the time Ford won for The Quiet Man in 1953, the awards landscape was shifting to the point where the Los Angeles Times described the SDG ceremony as "the first of a series of major motion-picture awards events." It was "quite a festive affair," added the Hollywood Citizen-News.

Tweaks, adjustments, and changes would continue for years. In 1953, Cecil B. DeMille was the first recipient of the Guild's lifetime achievement award. Awards for television were introduced the following year, along with the practice of recognizing the entire directorial team. Subsequently, categories for commercials, documentaries, news, and sports were added, as well as several service awards and special citations. The quarterly awards format was eliminated in favor of a large slate of nominees and then a roster of finalists, though it wouldn't be until 1970 that the practice of naming five nominees and then choosing a winner would stick.

By 2011, the awards had morphed into something very different from the low-key dinner and business meeting that had kicked everything off 62 years earlier. And yet, the awards were handed out over dinner, many of the top prizes were given out by fellow directors, all of the nominees got their moments onstage and in the spotlight, and the winners held the honor in particularly high regard because it came from their peers. And maybe the other trappings that weren't around for the SDG Awards in 1949—the stars, the red carpet, the paparazzi—are less important than the core of what was started all those years ago: directors honoring directors.

All of them, one way or another, would owe a debt to the directors who came before them, to the first ones to stand on a stage with the directors' medallion. They could well echo a line delivered by Zinnemann when he won the annual prize for From Here to Eternity in 1954: "You gentlemen have established a tradition, and I am only trying to follow along."