BY TERRENCE RAFFERTY

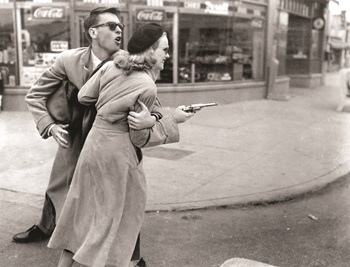

FEMME FATALE: Peggy Cummins and John Dall shoot it out in

FEMME FATALE: Peggy Cummins and John Dall shoot it out in

Joseph H. Lewis' Gun Crazy. (Credit: Warner Bros./Photofest)

American movie theaters never went dark during the grim days of the Second World War, but American movies did. Some of them, anyway—those moody, fatalistic, dimly lit crime dramas we now call, collectively, film noir. The French gave us the term, and maybe a little of the doom-drenched romantic sensibility that made these pictures so distinctive. And many of the best noir directors were European by birth or upbringing. Without filmmakers such as Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, Jacques Tourneur, Max Ophüls, Rudolph Maté, Fred Zinnemann, Edgar G. Ulmer, and Otto Preminger, noir as we know it would be a very different, and poorer, thing. Although the movies benefited from the shared Weltschmerz of the Continental contingent, it's just about impossible to imagine the two-bit tragedies of, say, Wilder's Double Indemnity or Siodmak's Criss Cross or Tourneur's Out of the Past in any place other than the land of the free and the home of the brave. The name notwithstanding, film noir is as American as a loaded pistol.

It's not just the tough-talking characters, the guys with good hats and bad luck and the itchy dames who love them. Those exist, in one form or another, almost everywhere. These hard cases often come to unfortunate ends in film noir, but what makes them so unmistakably American is that the violent outcomes always seem to come as a surprise to them. Unlike their gloomy counterparts in the French crime melodramas of the '30s, they'd expected a better outcome: They thought they were going to be on easy street. There's a weird, little-noted streak of optimism in film noir, a berserk hopefulness that may be, to some extent, a reflection of Hollywood filmmakers' sense that here, at last, was a form that allowed them to use every tool in their bag.

Robert Mitchum is awestruck by Jane Greer in Jacques

Robert Mitchum is awestruck by Jane Greer in Jacques

Tourneur's Out of the Past. (Credit: Photofest)

Noir is, first and last, a director's medium; it's all style. Compared to the studio gangster movies of the '30s, noirs tend to be relatively light on action, so the director has to hold the audience's attention by other means—to keep the atmosphere charged with menace while nothing much, really, is happening on the screen. In Wilder's Double Indemnity (1944), for instance, there's just one action set piece, a sequence in which Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray construct their elaborate alibi for killing her husband. The murder in Preminger's Laura (also 1944) takes place before the film has even begun. And in a few great, terrifying noirs, such as Ophüls' Caught (1949) and Alexander Mackendrick's Sweet Smell of Success (1957), the only violence is emotional cruelty. (In both cases, there's plenty of it.)

The signature look of film noir, for at least the first four or five years of its existence as a significant Hollywood form, was largely the creation of émigrés and B-movie directors. The narrative and verbal components were stripped, like parts of a hot car, from good pulp writers such as Raymond Chandler and Cornell Woolrich, but that's another story. The Europeans, most of whom had cut their teeth in the once remarkable German film industry, found these tales of world-weary tough guys more to their taste than anything the studios had dished out to them before, and gave the films the benefit of a complex, fully developed expressionist style that worked wonders on the modest material, the way a rich sauce can sometimes transform an iffy cut of meat. The expressionist manner of silent German cinema relied primarily on lighting and composition, rather than on intricate montage (which was the Russians' specialty). The noirs that established the conventions of the form in 1944—Double Indemnity, Laura, and Siodmak's lower-budget Phantom Lady—all featured dramatic camera angles, lots of evocative shadows, an unusual amount of glittery rain on the streets, and, except for a frenzied jazz sequence in Phantom Lady, rather simple, functional cutting. They made the world look sinister, fraught with peril, but somehow, unlike the wartime world outside, seductive: If you knew your way around, you could find pleasure in this darkness.

And the pleasures of film noir didn't have to be pricey. Laura and Double Indemnity were well-appointed studio productions with major stars, but Phantom Lady was a B picture, with relative unknowns, and thanks to Siodmak's ingenuity it looked just as sinfully attractive. If anything, you need more of those romantic shadows in a low-budget movie to disguise the cheapness of the sets. A single blinking neon sign outside a shabby hotel room could be made to go a long way; light streaming through Venetian blinds could give an otherwise mundane scene a sensual aura of mystery. B-movie directors such as Ulmer, Roy William Neill, and, especially, Anthony Mann seemed to understand that noir was a sort of form that actually thrived on limitations. A certain seediness was never out of place in noir people's sad stories, and the act of framing their crummy surroundings beautifully, enhancing them with imaginative blocking and elegant tricks of light, was somehow appropriate too: The director's aesthetic sense could, at times, reflect the characters' desires to see something better in their everyday lives. The barroom's a different place when a fine-looking woman walks in.

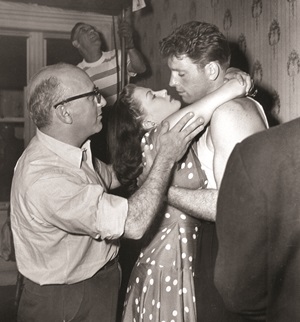

LOVE STINKS: Robert Siodmak, directing Burt Lancaster and Yvonne

LOVE STINKS: Robert Siodmak, directing Burt Lancaster and Yvonne

De Carlo in Criss Cross, used deep-focus compositions to show

the world encroaching on his heroes. (Credits: Photofest)

There are a lot of moments like that in '40s noir, the most memorable of which is probably Robert Mitchum's first awestruck gander at Jane Greer in Out of the Past (1947). For many directors, film noir was their Jane Greer, the sudden beauty that promised to change their lives. (Unlike her, it delivered.) Double Indemnity was just the third picture Wilder directed, and the first masterpiece of his long, shiny career. Laura was Preminger's first hit. Scarlet Street (1944) and The Woman in the Window (1945) were the strongest films Fritz Lang had made since his early days in Hollywood, a decade earlier, and arguably the best movie he directed in all his long years in America was a noir too: the fierce 1953 cop drama The Big Heat. The movie that kicked off Nicholas Ray's career was the young-thieves-on-the-run noir called They Live by Night (1949), and he followed that within the next few years with two more brilliant examples of the form, In a Lonely Place (1950) and On Dangerous Ground (1952). And Ophüls, who had bounced around Europe for a few years after leaving Germany in the early '30s and languished in Hollywood for nearly 10 years after that, became something like his old self again in his two superbly self-assured 1949 noirs, Caught and The Reckless Moment.

Film noir was perhaps a bit too low-rent for many of the established directors of the time; John Ford and Frank Capra, for example, never tried their distinguished hands at it (probably wisely). So the field was wide open for the émigrés, the newcomers, and the B-picture craftsmen who had been slogging their way through grisly assignments at minor studios. Noir gave all of them a chance to show they could do more than a Poverty Row Western programmer or (at the high end) a string of Boston Blackie movies. You can feel the excitement of a young director such as Robert Wise, for instance, in his crisp, evocative work in the great ringside noir The Set-Up (1949); or of a weary veteran such as the almost forgotten Roy William Neill, who after years of studio hackwork and dozens of routine bill fillers gets a crack at a wonderful Woolrich story and makes his most enduring film, Black Angel (1946). (It was also his last. He died soon after, at 60—a noir hero's end, abrupt and unfair.)

CRIME WAVE: Sheila Ryan and John Ireland in Anthony Mann's

CRIME WAVE: Sheila Ryan and John Ireland in Anthony Mann's

Railroaded. (Credit: Photofest)

Farley Granger and Cathy O'Donnell are thieves on the run in Nicholas

Ray's They Live by Night. (Credit: Warner Bros./Photfest)

Noir material, that is to say, was usually served best by filmmakers with something to prove and nothing to lose, maybe because they knew just how their characters felt. And that what-the-hell attitude, applied to stories that reflected both the hopes and the disillusionments of American life in a scary time, seems to have freed those directors to experiment and invent. Film noir is often thought of as a single, very specific style, but the more you watch the more different these movies seem from one another. The good directors all seem to have taken the form personally, and to have bestowed on it their best, most expressive individual styles. The dry lucidity of John Huston's classic caper movie The Asphalt Jungle (1950) is very, well, Hustonian, but he takes it a little further than usual in several sequences that largely dispense with music and dialogue. Zinnemann, in his characteristically understated (and underrated) 1948 noir Act of Violence, also plays effectively with sound and its absence—in this case, the oddly ominous sound of a limping war veteran dragging his foot as he stalks a man he means to kill. In Criss Cross (1949), Siodmak uses deep-focus compositions much more extensively than he had in Phantom Lady, and to extraordinary effect. In scene after scene, the shot opens on one or two figures in the foreground and then allows the background to fill up gradually, encroaching on the hero's and the heroine's illusory sense of isolation from the world.

Some directors keep the camera moving: Ophüls, of course, but also John Farrow in The Big Clock (1948), Ray in all his noirs, Richard Quine in Pushover (1954), and, perhaps most spectacularly, Joseph H. Lewis in his outlaw-couple classic Gun Crazy (1950), in which, in one long sequence, he plants the camera in the back of the bank robbers' getaway car and just leaves it there, without cutting, as they make their frantic escape. Others, such as Mann, rarely track or pan, preferring to achieve their effects entirely through lighting, composition, and precise cutting; his low-budget noirs Railroaded (1947), T-Men (1947), and Raw Deal (1948) are among the purest examples of the German expressionist style in American movies. The editing styles of noir are impressively varied too, and often highly idiosyncratic: Mann uses straight cuts almost exclusively; Ray throws in dissolves at every opportunity. Film noir was a black cat that crossed the path of American culture in the '40s, and every director seemed to find his own way to skin it.

DOUBLE CROSS: Billy Wilder directs Barbara Stanwyck and Fred

DOUBLE CROSS: Billy Wilder directs Barbara Stanwyck and Fred

MacMurray in Double Indemnity, one of the early noirs that

established the conventions of the form. (Credits: Photofest)

Film noir was always a strange hybrid. Reams of deadly academic prose have been devoted to the not very interesting question of whether it is, properly speaking, a genre, or a style, or what. (I'd say it's a bit of both, and that I know it when I see it.) The genre/style/whatever was even at its late-'40s height a surprisingly flexible form, but in the '50s, with the advent of television and its audience's different demands, the fragile, elusive temperamental affinities that linked one film to another and made them seem brothers in noir began to come apart. In story terms, the films started to focus more on law enforcement than on the loners, and drifters, and lost souls who had peopled the films of the '40s, and the percentage of happy endings—fairly low in the early years—rose steeply. Often, justice triumphed, which doesn't seem a noirish outcome at all. The look of the films gradually changed, too, shading away from the romantic, high-expressionist style toward the brighter, harder-edged style of TV cop shows. Fewer and fewer were shot on studio sets, more and more on location. That semi-documentary look was featured in a handful of '40s noirs, notably Henry Hathaway's Kiss of Death (1947) and Jules Dassin's The Naked City (1948), but it became omnipresent in the '50s. Even the shape of the movies changed, from the Academy ratio—which was good for creating a noirish sense of claustrophobia—to widescreen formats. (The films remained overwhelmingly black and white, though.) Film noir had, in the best American style, made itself up as it went along; in the '50s it woke up to a full-blown identity crisis.

Lang, with his characteristic sang froid, cannily blended the old noir mode and the new in The Big Heat, but most of the older directors floundered, or abandoned the form entirely. Younger B-movie directors such as Phil Karlson (The Brothers Rico, 1957) and Don Siegel (The Lineup, 1958) seized their chances. And the most interesting films noirs of the period were the craziest—the ones that fully embraced the form's growing lack of coherence. Samuel Fuller's 1953 Pickup on South Street contrives to introduce Communist spies (they're very sweaty) to the world of noir, and to tangle them up with a cynical pickpocket who works the subways and lives in a shack in the harbor. And the plot isn't even the nuttiest thing about Pickup on South Street. That distinction falls to Fuller's direction, which is truly, madly, deeply eccentric, excitingly unpredictable from scene to scene, and even within a scene. The silent opening sequence, in which the pickpocket hero lifts a purse from a straphanger, is a classic bit of montage, but for the rest of the picture the cuts never come where you'd expect them to, and the camera movements are more unpredictable yet: They look improvised and spur of the moment. And it works, in this bizarre context. The camera moves like a guy checking a strange room for hidden mikes.

END OF THE LINE: Orson Welles used every trick in the noir

END OF THE LINE: Orson Welles used every trick in the noir

book on Touch of Evil, with Charlton Heston and Janet Leigh.

Howard Duff in Jules Dassin's The Naked City. (Credits: Photofest)

Robert Aldrich's Kiss Me Deadly (1955) takes that amped-up paranoia a little further, both in its plot—which revolves around the other great fear of the 1950s, i.e. The Bomb—and in the hyperkinesis of its direction. But the undisputed champion of weird '50s noir is Orson Welles' baroque Touch of Evil (1958), which embodies the split personality of the form in just about every possible way, beginning with its setting on the border between the United States and Mexico. In the virtuosic opening, a nearly five-minute-long tracking shot, a car crosses from one side to the other, then blows up. After numerous viewings, over many years, I still can't remember which country the car explodes in, and for a lot of the movie even the characters don't always seem to know what side they're on. It matters to the impossibly complicated plot, but it's barely relevant to the experience of the film. Even after its recent restoration, which somewhat enhanced the film's narrative coherence, Touch of Evil remains at its heart a flamboyant, darkly gleeful exercise in sensory stimulation. Welles uses every trick in the noir playbook. There are wildly canted angles and shots lit with the starkest contrast of blacks and whites; there are jittery montages scored by unnervingly loud source music; there's an interrogation scene shot in the hard, flat docudrama style, with long takes. And Welles allows for an almost deranging variety of acting styles—including his own sodden, mock-Shakespearean take on the bad American cop.

Touch of Evil is a kind of inspired mash-up of the themes and techniques of film noir. There were a few noirs after it, but Welles' movie is really the end of the line. Its decadence is damn near Baudelairean; it blooms gorgeously, a mutant flower in the ruins of a once great cinematic form. And it gives the era a fitting send-off. Film noir didn't end up on easy street because nothing, and no one, does. But it went out in style.