BY LYNDON STAMBLER

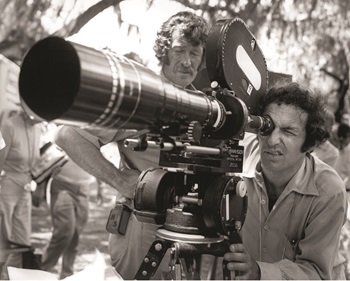

FORESIGHT: As a result of Elliot Silverstein's vision, the Guild launched its

FORESIGHT: As a result of Elliot Silverstein's vision, the Guild launched its

successful campaign for a Director's Cut. (Credit: Photofest)

It's hard to believe, but there was a time in Hollywood when a director might not have any input in the final version of a movie or TV show. The producer would handpick a film editor who made the final cut, and the director was frequently locked out of the editing process. Such was the case when Elliot Silverstein directed an episode of The Twilight Zone called "The Obsolete Man," which aired June 2, 1961.

But Silverstein refused to accept the status quo, resulting in one of the more difficult negotiations between the Directors Guild and producers. Ultimately the Guild prevailed and secured for directors what has become one of the cornerstones of their craft—the Director's Cut.

Silverstein had come to Hollywood after years of directing in New York's freewheeling world of live television. Back East, he was used to calling his own shots from the console. But in the late '50s and early '60s, when he embarked on a career in Hollywood, he entered his own twilight zone.

"The Obsolete Man" was a Kafkaesque tale written by Rod Serling about a neo-Nazi state that banned books and obliterated individual and religious freedoms. Burgess Meredith played a Bible-toting librarian who is sentenced to death for "obsolescence" by a chancellor, played by Fritz Weaver. Silverstein staged the episode in a style reminiscent of German expressionist films of the 1920s; the sets—including 25-foot doors and a 20-foot lectern from which the chancellor issued the death edict—evoked a stark, sterile world.

When Silverstein finally viewed the editor's rough assemblage for the episode, everything seemed as he had envisioned it, until he got to the final scene in which the guards turn on their ruler and condemn him to death. Inspired by a nightmare, Silverstein had directed the guards to initially growl without making a move. Only when the tension reached a boiling point did they close in, automaton-like, to attack the chancellor as he pleaded for his life.

But the editor didn't see it that way. Rather than have the guards stand pat, he cut it so that the guards moved in immediately for the attack.

"You don't understand," Silverstein said, asking the editor to restore the scene to his original concept.

"Well, I don't want to cut it that way," the editor said.

"You what?" Silverstein responded, his blood boiling.

"I don't want to cut it that way. It's ridiculous," the editor insisted.

They reached a bitter compromise with the help of the producer, Buck Houghton. But Silverstein, who went on to direct such films as Cat Ballou and A Man Called Horse, is still pained when he watches the episode.

But in another sense, the ramifications of that chopped show moved well beyond that episode. The dispute sparked the creative rights movement at the Guild and led to the landmark directors' Bill of Creative Rights.

The Twilight Zone editor chose the wrong director to tangle with. Silverstein, a feisty man who had grown up on the mean streets of Dorchester, Mass., near Boston, was ready for a fight. Silverstein immediately began calling other directors. "Are you having this kind of problem?" he asked.

Yes, they had.

Silverstein contacted Joseph Youngerman, the executive secretary of the Guild, and discovered that the director's rights were limited. They had the right only to view the first rough cut and to communicate improvements to the associate producer. That was unacceptable to Silverstein and to other directors. "What does 'view' mean?" Silverstein recalled during a 2002 interview. "What is a first rough cut? What is an associate producer? Why do you only get a chance to make improvements? Aren't we supposed to be creating something?"

Silverstein wanted answers, and Youngerman started him on the process. To make any changes in the system the Guild would have to negotiate with the studios. Guild President George Sidney authorized the creation of a committee on Nov. 12, 1963. At an early meeting, Silverstein, the committee chair, recalled, "The blood…poured out onto the table in that old DGA building. You could drown in it." In response, he asked, "Well, why don't we do something about it?"

Variety announces the director's Bill of Creative

Variety announces the director's Bill of Creative

Rights in 1964. (Credit: Variety)

At first, members considered calling it the Artistic Rights Committee, but as Silverstein put it in a 1986 oral history interview, "In a town that considers itself industrial and professional, the use of the word 'creative' would provoke less hostility than the use of the word 'artistic.' " After all, they were conducting labor negotiations not parlor room debates. So they decided to call it the Committee on Creative Rights and the 18-member group, which included Robert Altman and Sidney Pollack, met each Sunday for six months. Their first act was to create "A Bill of Creative Rights."

"It was a manifesto of the young Turks from New York invading Hollywood, and now we were going to say how things should be done," Silverstein said.

The bold document, released in April 1964, started by defining the role of the director as someone who should take part in all aspects of the motion picture process. "[The director] translates a motion picture script, story, or idea into visual and aural terms and arranges the images and sounds in a relationship he considers proper," the document read.

"We wanted to cast ourselves as the people who made the films," Silverstein explained. "Everything else was stuff on the palette. But we were making the painting."

The most important declaration concerned the Director's Cut. "The arrangement of the recorded images and sounds in a relationship the Director considers proper shall be known as the 'Director's Cut,' " the document read. "It is the Director's creative right and obligation to prepare this cut and he must be given the time he deems necessary to fulfill this function."

With this daring stroke, the committee elevated the status of the director. "I wanted a Director's Cut. I wanted to see it our way once," Silverstein stated.

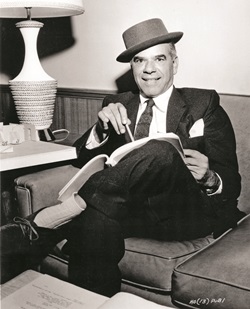

NEGOTIATIONS: Frank Capra proposed a bold solution

NEGOTIATIONS: Frank Capra proposed a bold solution

when studios balked at a Director's Cut. (Credit: Everett)

The Negotiating Committee members knew that getting the studios to agree to the demands put forth by the Creative Rights Committee would be difficult, to say the least. The Guild turned once again to former Guild President Frank Capra to chair (with John Rich and David Miller) the negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). When the directors presented their idea for the "Director's Cut," their adversaries were initially confused, in part because they were professional negotiators who were not intimately involved in making movies and TV shows.

"The Director's Cut…did not exist at that time," Silverstein explained years later. "There was some general right of consultation, but not the specific right to make a Director's Cut. There was a first rough cut, first cut, rough cut—no way to tell what they were without further description. Director's Cut was to be definitive; it was to be the cut the director made, the cut that he or she wanted to appear on the screen."

It made perfect sense to the directors who helped develop the script, directed the actors, and gathered the raw footage. "To have the baby pulled away from us [when it came time to pull the material together and realize our original vision], seemed to be cruel and inhuman punishment," Silverstein maintained.

But the other side—led by Charles Boren, AMPTP executive vice president—was concerned that any change could stall production. The producers wanted to know, as Silverstein recalled in his oral history, "What if the director doesn't show up? What if he stays in [the cutting room] forever? It's gonna cost us money. The clock is on. The in-dustry will collapse. The companies will go under."

The directors and the studios had reached an impasse. But during a caucus, Capra suggested an elegant solution. "Boys [there were no women on the first committee], "you gotta want to give before you deserve to take. How much do you care, boys?" Silverstein remembered him saying.

They cared a lot.

"No, no, we gotta show 'em," Capra continued. "We're gonna have to do it for love and not for money."

Capra's idea was that if a director failed to show up to make the Director's Cut, the DGA would pay to fly in one of 12 top-notch directors on a preapproved list to finish production. "By God, we'll start with David Lean," Capra said. Alfred Hitchcock, John Huston, and Billy Wilder were among the names believed to have been mentioned, although it is unclear whether Capra had actually had discussions with any of these directors, or it was just a grand ploy.

They returned and presented the idea to the producers—a moment forever etched in Silverstein's memory. "Charles Boren turned white for a moment," Silverstein recalled. "His jaw dropped, and there was a silence which now as I look back over the years felt like three minutes; it must have probably only been about 15 to 30 seconds, but there was a dead silence in the room.

"We were saying, 'We want to work for love, and we won't take any money for it,' " Silverstein said.

They had removed the producers' objections. But when the producers returned after the break, the answer was still no. According to Silverstein, Boren said, "Gentlemen, we thank you for this gracious offer. We think we understand now the importance of what you're talking about and we will decline your offer, but we will seriously consider this idea for the Director's Cut."

But the directors knew they had overcome their objections. And later that year, in the autumn of 1964, the producers agreed, after some backpedaling. The directors got the Director's Cut, part of a directors' Bill of Creative Rights, in their new contract.

However, even with the establishment of the Bill of Creative Rights, there were still other significant issues and the Guild continued to build on that initial victory. As creative rights became more and more important in DGA negotiations, they were addressed in a forum separate from the economic issues that were negotiated by the studio labor relations lawyers and executives. In subsequent negotiations, Guild directors would deal directly with studio chiefs for matters relating to creative rights and credits. The guiding principle of these meetings was that directors and studio heads could come together as creative people and solve problems in their own fashion.

This has produced major accomplishments along the way. For instance, in 1973 the producers recognized that directors could be undermined, and the final product hurt, by people on a production who might want to take the director's place. So they agreed that a director cannot be replaced by anyone who had previously been a part of that production. This provision has come to be seen as the cornerstone of all director's rights. In 1981, directors who finished shooting principal photography won the right not to be summarily fired, to be entitled to direct any retakes or additional scenes, and to be present and consulted at all times in postproduction. Other gains made in 1981 included the right for directors to select their first assistant director. Over the years, the Creative Rights Committee continued to make other improvements to the working life of directors, such as securing the right to control the use of video assist, and to participate in the MPAA rating appeals process and make any necessary changes to secure a desired rating. The Guild consistently fought to bolster the rights of TV directors. One prominent success in this area was the campaign to curtail abuses related to late script delivery, which had been impairing the director's ability to perform his or her job.

Robert Ellis Miller (left) and Jeffrey Hayden (right) were members of the

Robert Ellis Miller (left) and Jeffrey Hayden (right) were members of the

first Creative Rights Committee. (Credits: Photofest)

"The Director's Cut was a serious artistic step in Guild history," recalled director Robert Ellis Miller (The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, Reuben, Reuben), who was a member of the original committee. "I'm very proud to have been a part of it. It changed everything."

But the advances didn't come easy. "Those were hard fought and hard won battles," said Jeffrey Hayden, another member of the committee, who directed hundreds of episodes for TV including The Andy Griffith Show, Magnum, P.I., and Cagney & Lacey.

"We argued vociferously and passionately," Silverstein noted. "We didn't get everything in the first year, but we continued year after year until we did."

Hayden remembers some of those difficult battles, such as getting scripts before they went into production. Another bone of contention was providing directors with an office at the studios so they could have private meetings with actors, agents, or producers. "They didn't want to give us three walls and a door," said Hayden. "I'm not exaggerating. It took a couple of years."

The directors eventually won concessions on most of their key issues. "I can only tell you," Hayden said, "that over the years, from the early '60s through the '70s, the progress made by the Creative Rights Committee of the Guild was extraordinary."

Although the negotiations were oftentimes arduous and contentious, they more often than not led to a mutual understanding between producers and directors. "As directors, we negotiate all the time on the set," Silverstein said. "We enjoy negotiating. So do the producers. I hope down through the years this procedure of dealing with one another respectfully and dealing with the problems we have will continue."

Today's young directors have surely benefited from the earlier victories of the Creative Rights Committee. "All of the creative rights language flows from this idea of the director having the right to a cut. But it had to be demanded and negotiated for," noted Steven Soderbergh in a short documentary shown at the DGA Awards this year celebrating the Guild's 75th anniversary.

In the same presentation, Paris Barclay added that "The chance not just to direct [a show] and to call every shot, but to put it together in the manner that I think is best—that's a critical creative right that I wouldn't trade for anything."