BY GARY GIDDINS

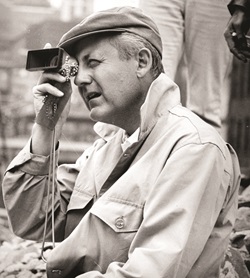

(Credit: Everett)

(Credit: Everett)

Despite a filmography of undoubted classics in almost every genre and at almost every price tag, Robert Wise, a former president of the Directors Guild of America and winner of two DGA Awards, is often regarded with suspicion by critics. He is routinely praised with the backhanded admiration due a craftsman and all-around take-charge professional rather than an artist, let alone a visionary. Often he is touted exclusively for his early work—The Body Snatcher, Blood on the Moon, The Set-Up—made before, as one critic put it, "growing budgets made him reluctant to take chances." Yet when did Wise take more chances than in such late-career, extremely personal, and risky projects as The Sand Pebbles, Star!, and The Andromeda Strain? A revisionary evaluation is overdue.

The charge that Wise's ambition led him astray from small classics to blockbuster moonshine stems from his most commercially durable achievement, The Sound of Music, which he produced and directed in 1965. Say what you will about Rodgers and Hammerstein's carousel of nuns and Nazis, Wise's adaptation is nothing if not a directorial triumph. Working with cinematographer Ted McCord, he opens the film with a stupendous aerial shot of the Alps that tracks directly into the arms of an enraptured Julie Andrews, creating an emotional charge that is purest cinema. He embraces the material while cutting the treacle with droll editing and a shrewd sense of tempo, and the payoff is a picture that remains a familial rite of passage, generation after generation, not unlike The Wizard of Oz. And in allowing Christopher Plummer to play Captain Von Trapp with arch disbelief in everything going on around him, Wise even provided an outlet for cynics in the audience.

Wise was 50 years old when he made The Sound of Music, and a veteran filmmaker of a sort we won't see again. He had learned cinema from the ground up: carrying prints, patching film leader, assisting in the editing of sound and film, before editing solo. Within a year of his first assignment, Orson Welles tapped him to edit Citizen Kane (1941), earning him the first of several Academy Award nominations. It was while cutting Welles' second film, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)—at RKO's insistence when Welles disappeared to South America on another project—that Wise was obliged to shoot stopgap transitions, his first scenes as a director. Wise's reputation was sullied by his participation in the studio's ruthless winnowing of a masterpiece (a third of the original film was destroyed); yet it was Wise, representing Welles' interest amid what had become an adversary camp, who salvaged most of the footage, guaranteeing the survival of a sublime work. Welles, in his thunderous denunciations of the studio, remained courteous regarding Wise's involvement.

The Haunting (1963) (Credit: Warner Bros./Everett)

The Haunting (1963) (Credit: Warner Bros./Everett)

Baptized by fire, Wise, at 28, learned that the movie business involved a persistent negotiation among art, commerce, and sometimes arbitrary displays of power. He had come to Hollywood from Indiana nine years earlier, in 1933, having abandoned college in the worst year of the Depression. Finding a job and an industry he loved, he faced every situation squarely, including his more rewarding second turn behind the camera—yet another fix-it job.

Producer Val Lewton hired Wise to take over the childhood reverie and ghost story The Curse of the Cat People (1944), which was running behind schedule. He completed it in 10 days, earning recognition for the light, naturalistic touch he brought to the supernatural. That touch saw him through two more Lewton productions, Mademoiselle Fifi (1944, not on DVD) and a deliriously inventive version of Robert Louis Stevenson's The Body Snatcher (1945). Beyond the fogbound atmospherics and meticulous art direction of Body Snatcher, Wise elicited two of the greatest performances in the horror genre, as Boris Karloff and Henry Daniell match wits in tensely menacing conversations balancing stark explosions of violence. Wise's visual conceits are more memorable than Lewton's good literary dialogue: a street singer disappearing into the shadows, followed by the malevolent Karloff; Karloff's death, as witnessed by a cat; and an astonishing finish in which the director made the most of his editing skills featuring a runaway hearse, flashes of lightning, a terrified driver, and a baleful corpse.

Promoted to A films, Wise made the brooding, exquisitely photographed Robert Mitchum Western Blood on the Moon (1948, unavailable on DVD), and the noir classics Born to Kill (1947) and The Set-Up (1949). Born to Kill turns Raymond Chandler's template of the incorruptible private eye upside-down, substituting a corrupt mercenary (Walter Slezak: squat, sweaty, effete) who walks away from a litter of dead bodies, including Lawrence Tierney's psychopath and Claire Trevor's delusional society girl, whose awareness of her own rottenness echoes lines from the Chandler script for Billy Wilder's Double Indemnity in 1944.

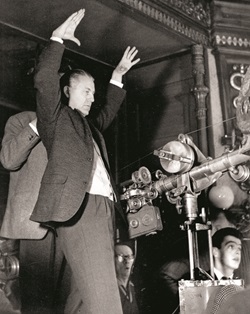

I Want to Live! (1958) (Credit: Everett)

I Want to Live! (1958) (Credit: Everett)

The Set-Up won the Critics' Prize at Cannes and remains one of the best boxing films, memorable for Robert Ryan's performance as a palooka on his last legs and Wise's use of a real-time scenario (later used in High Noon). His rapid editing scheme makes the fight sequences creditable and the bloodthirsty fans chilling. Wise's contempt for the kind of people who attend boxing is laid on thick and would figure in subsequent boxing sequences from the dire Helen of Troy (1956, a Euro-dubbed misfire); to the sentimental biography of fighter Rocky Graziano, Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956); the choreographed knife fight in West Side Story (1961); and the eight-minute boxing sequence in The Sand Pebbles (1966).

By 1951, when he had gone to Fox and made the most admired entry in the postwar science fiction cycle, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Wise's work had begun to exhibit consistent thematic and stylistic concerns. For one thing, he was an unreconstructed liberal—favoring internationalism, civil rights, peace, and a belief in the moral certainty that right makes might. In the case of The Day the Earth Stood Still, that certainty encompasses the threat of an interplanetary consortium that will blow Earth to smithereens if it doesn't get its nuclear act together. An incisive portrait of Red Scare paranoia, the film is notable for the womanly self-possession of the character played by Patricia Neal (no soap opera mom, she), a high regard for science and logic, and a relaxed approach to the Christ parable. In a DVD commentary, Wise claims ignorance of the religious theme (the spaceman played by Michael Rennie is killed and resurrected and goes by the name of Mr. Carpenter), preferring to focus on such directorial challenges as not getting the robot's knees to buckle. Wise had become increasingly absorbed in the way things work: the operation of a flying saucer or a submarine, the mechanics of the gas chamber or a gunboat's engine room.

Wise directed 18 films in the 1950s, bringing stylish confidence to an extraordinary variety of material (most of it available on DVD), including a riveting inquiry into business ethics, Executive Suite (1954), in which the conspicuously bare set design helps set off sparks generated in verbal standoffs by an all-star cast (Barbara Stanwyck, William Holden, Fredric March). He gave James Cagney a meaty star turn in the Western Tribute to a Bad Man (1956), and maxed the energy level in a series of brisk war films, notably The Desert Rats (1953) and the dramatically measured Run Silent Run Deep (1958), a submarine adventure so tense and authentic (Wise built a submarine-sized set) that the viewer is free to relish or ignore the Moby Dick parable of a commander willing to risk life and crew to track down one particular enemy ship.

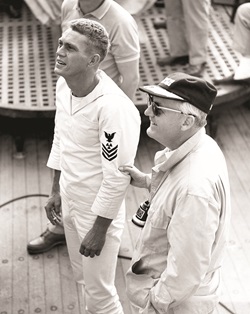

The Sand Pebbles (1966) (Credit: Photofest)

The Sand Pebbles (1966) (Credit: Photofest)

At decade's end, Wise revolutionized the use of jazz in movies with two of his most accomplished works, I Want to Live! (1958) and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959). The first is remembered for Susan Hayward's Oscar-winning turn and the unflinching depiction of California's gas chamber, but it was also the first film to recruit a jazz composer, John Mandel, to combine onscreen improvisation and scored music, including a long opening sequence with no dialogue. For Odds Against Tomorrow, a film about a heist foiled by racial hatred (superb work by Robert Ryan, Harry Belafonte, and Ed Begley), Wise hired John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet, personally coached him in the technique of using a click track, and received in turn a classic score, including the jazz standard "Skating in Central Park."

Still, Wise had never made a true musical until 1961, when he was asked to work with Jerome Robbins in adapting West Side Story, a film compromised by miscasting in the central roles, but well remembered for its aerial shot of New York, the dramatically staged dance numbers, and the scene-stealing supporting work of Rita Moreno, George Chakiris, and one of Wise's favorite character actors, Simon Oakland. Before embarking on The Sound of Music, he made the marvelous ghost story The Haunting (1963), with its striking sound effects and oddly candid lesbian subtext. Then, after crowning the box office with Austrian dirndls, Wise embarked on the most intricate and politically trenchant production of his career, The Sand Pebbles.

The DVD restoration of The Sand Pebbles is perhaps the best way to experience a flawed but genuinely epic romance that, despite excessive length and embroidered story line, radiates Wise's commitment to re-creating 1920s China, staying true to novelist Richard McKenna's critique of American imperialism, and building to a surprisingly existential denouement. When Wise had gone after nuclear proliferation, capital punishment, and racism, he was on the side of the angels, but in 1964, when he began preproduction on The Sand Pebbles, the country had not yet unified in despair over Vietnam. Shooting on the Yangtze River, Wise told a story set against China's overthrow of warlords in defiance of American naval interference, and managed to make it a rousing adventure—the fictitious battle scene involving a blockade is stirring stuff by any standard—and an exercise in futility. Steve McQueen, giving the most nuanced performance of his career, dies asking why.

Wise's third and finest musical, Star! (1968), based on the career of Gertrude Lawrence, a stage personality who meant nothing to most moviegoers, is the clearest evidence of his ability to stage complicated musical numbers with imagination and brio; a legendary box-office failure in its day (Julie Andrews as a wanton entertainer all but repealed the sweetness of The Sound of Music), it glimmers on DVD in its devotion to theatrical history. The Andromeda Strain (1971) was ahead of its time in Wise's unremitting attention to high-tech gadgetry, some of it intentionally bewildering; his decision to use a bland, largely unknown cast emphasizes a connection between man and machine. Military ambition and secrecy is the villain, as it was in The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Sand Pebbles. The best rejoinder to those who persist in viewing Robert Wise as a craftsman indifferent to the substance of his films is to look again at the films.