BY AMY DAWES

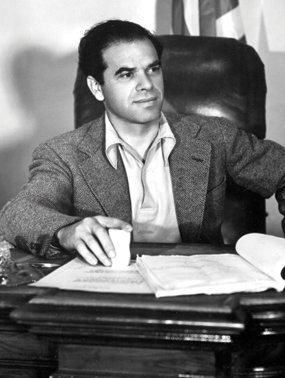

MANO-A-MANO: Frank Capra (top) and Joseph Schenck (bottom),

MANO-A-MANO: Frank Capra (top) and Joseph Schenck (bottom),

president of the Motion Picture Producers Association engaged in a

classic chess match in 1939 before the Guild finally prevailed

and gained acceptance. (Credits: EVERETT/AMPAS)

In its final days, the long battle to win studio recognition of the Screen Directors Guild would come down to a face-off between two distinct personalities. In one corner was Joseph Schenck, iron-willed, craggy-faced president of the Motion Pictures Producers Association and chairman of 20th Century Fox. Schenck, a Russian Jewish immigrant who spoke with a thick accent, was a man so steadfast in his opposition to organized labor that he eventually spent several months in prison for strike-related illegal payoffs.

In the other corner was Frank Capra, the hugely popular director of man-in-the-street comedies such as It Happened One Night and Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. A short, dark scrapper who had emigrated from Sicily, Capra was riding the upward trajectory of a meteoric career, and was both president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the newly elected second president of the Screen Directors Guild. He thrived on being in the middle of things, and described himself as "itching to roll in the dirt with the movie moguls." Neither was a man to be trifled with, yet that's just the strategy Schenck seemed to choose when he engaged in a round of psychological belittlement aimed squarely at Capra.

Up until that point, the struggle for Guild recognition had involved nearly three years of fruitless negotiations. In early February 1939 the producers appointed a new negotiating committee and called a meeting with the directors on the ninth. That night, they declared they would not negotiate with the SDG unless it threw the assistant directors out of the Guild. This was particularly irksome to the directors because the same demand had been made - and rejected - nearly a year and a half earlier. Fed up, they walked out of the meeting.

"It was obvious to us," Capra said later, "that Joe Schenck was playing a game of meet and stall, meet and stall, until directors got sick of the Guild idea." In the versions that film historians have written of what happened next, the details sometimes vary. The account Capra gave in his autobiography, The Name Above the Title, is undoubtedly the liveliest.

As he tells it, Schenck phoned the offices of the SDG the next day to request a private meeting with Capra, who was in the midst of preparing to shoot Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. He asked Capra to stand by for a call, and despite the demands on his attention, Capra waited all day. The call never came. When Capra phoned Schenck the next morning for an explanation, Schenck apologized and asked the SDG president to come to his office alone at 3 that afternoon. Capra reported to Schenck's office at 3 p.m. and learned that he was out. Schenck's secretary informed him that the studio boss had gone to the racetrack hours earlier and had not returned. Capra was furious, but he didn't hesitate.

"My hackles rose," he recalled in his book. "He was trying me on for size." Capra jumped into his car, raced over to Santa Anita and once there, tracked Schenck to his private box. The imposing Schenck, whom Capra described as "the sharpest poker player in Hollywood's high-stakes games," behaved as if nothing was amiss. "Well, look who's here, Frank Capra!" he declared. "Come in, come in. I've got tips to give you on the next race." Capra said he played it cool. "No thank you, Mr. Schenck," he replied. "I just drove out here to give you a tip. The next time you ask me for an appointment, I'll be there. And so will you - with your hat in your hand."

Capra drove back to work, smoldering. He called a special meeting of the SDG board Monday, and filled the members in on Schenck's behavior. They were outraged. If it was true, as negotiating committee member Rowland V. Lee declared, that things had come to this insulting impasse because the Guild had thus far failed to press the producers hard enough, the time for hesitation was over. Capra spoke up: "I warned them that Schenck would only yield to power; that we must move quickly, gamely and lethally - or forget the Guild."

At the behest of W.S. Van Dyke, Capra placed a call to the Guild's attorney in Washington, D.C., Mabel Walker Willebrandt, urging her to return to Los Angeles for a final round of negotiating. The committee was determined that this would be the end of it. To demonstrate its intent, the Guild demanded the producers send a telegram to Willebrandt by Feb. 16 promising to conclude negotiations for a basic agreement without further delay. When the telegram failed to appear by the day before the deadline, Capra proposed a bold strategy to the board.

"We discussed possible power moves," recalled Capra. "Some members were for calling an emergency meeting of all directors and asking for a strike vote. I suggested a more immediate power play: Disrupt the upcoming Academy Awards banquet."

Capra's investment in the Awards ceremony was enormous. He had not only invested four years as Academy president in building up the membership and position of the Academy, but he was slated to preside as master of ceremonies on the big night, and his own picture, You Can't Take It with You, had been nominated for seven Oscars. Given the conflicts of his position, Schenck may have assumed that he would be incapable of such a move. If so, he had underestimated the shift in Capra's loyalties. Capra was now firmly on the side of the directors.

"First, I will immediately resign as president of the Academy, and withdraw as master of ceremonies," he told the SDG board. "Reason: the rude, contemptuous attitude of the Motion Pictures Producers Association toward the Screen Directors Guild and its officers.

"This accusation," he predicted, "will make the world's front pages." The second move, he suggested, was to call an emergency meeting of all directors in the Guild for the following night. Urgent telegrams were sent out, and news of the meeting was leaked to the trade papers, which played it up big.

On Thursday, Feb. 16, 1939, more than 250 angry film directors and assistant directors assembled at the Hollywood Athletic Club. The officers filled them in on the humiliating on-again, off-again negotiations, and suggested that management was merely stringing them along with the goal of destroying their morale. When the tale was told of how Capra had to chase Schenck out to Santa Anita after being stood up on back-to-back appointments, the membership exploded. Lee rose and said, "If the producers refuse to negotiate, they were not only letting down the directors but the whole industry." A strike vote was called, and the motion was immediately seconded. As chairman, Capra tried to calm the meeting down. "But then I realized," he recounted later, "that a strike vote and the Academy boycott would give me a one-two punch - the ace-king showing that might force Schenck to throw in his hand."

The vote to strike, if it came to that, was approved unanimously, as was Capra's resignation from the Academy and a boycott by directors of the Academy Awards. Willebrandt was instructed to send an ultimatum by telegram to the attorney for the Producers Association: Management had 24 hours to sign an agreement recognizing the Guild as the bargaining agent for directors and their assistants. If no positive response arrived within 24 hours, Capra would release the ultimatum to the press. The line had finally been drawn. Despite his determination, Capra acknowledged the extraordinary conflicts of his position.

"I didn't sleep much that night," he admitted. "A boycott of the Academy would be unpopular enough - but a strike would be a declaration of war. It would be asking dedicated filmmakers to be more loyal to their union than to their films." At stake for him was the fate of Mr. Smith, and he wondered whether he could walk out on it. Furthermore, a boycott would sink the Academy, which four years before had granted him a sweep of five Oscar wins, including best director, for It Happened One Night.

PLAYERS: A headline on The Hollywood Reporter announced that

PLAYERS: A headline on The Hollywood Reporter announced that

directors and producers had taken their battle as far as they could.

(Left to Right) Founding members Howard Hawks and W.S. Van Dyke fought for the

(Left to Right) Founding members Howard Hawks and W.S. Van Dyke fought for the

Guild, while Samuel Goldwyn maneuvered for the producers. (Credit: AMPAS)

"The last thing I wanted to kill was the Academy," he said in a 1985 interview. But if that's what it took to achieve recognition for the Directors Guild, he was resolved to do it. Hedging its bets, the Guild leaked to the trade press rumors of a possible strike and of Capra's threat to resign as Academy president. The next morning, Joe Schenck called the SDG office, saying that he and several other studio heads were in Palm Springs, where he said "a sandstorm" was taking place that would delay their return. He sought a day's extension on the time limit. The answer was no. They must have hurried straight back, for Capra soon received a direct call from Schenck saying that the film company heads and their attorneys were meeting in his office at 20th Century Fox at 4 p.m. Would Capra please come to the meeting, alone?

"Would it save time," Capra said he retorted, "if I went directly to Santa Anita?" Schenck chuckled. "As a personal favor, please come out, Mr. Capra," he replied. "I remember about the hat too." When he arrived at the lot, Capra was led into the executive office, where the scene as he described it was this: "A dozen of Hollywood's high-and-mighties and their attorneys slouched with flushed faces; some were coatless. They greeted me with harsh stares and harsher questions: 'You've got your nerve...' and 'Who do you think you are - sending us ultimatums?'" Present was the entire executive committee of the Producers Association, including Schenck, Darryl F. Zanuck, Samuel Goldwyn, Harry Cohn, Louis B. Mayer, Jack and Harry Warner, Frank Freeman of Paramount, and Pandro S. Berman and J.R. McDonough of RKO, along with six attorneys.

Capra, the great storyteller, described what happened next like this:

"Gentlemen," I answered, as pious as Mark Twain's Christian who held four aces, "I am a servant carrying out an order from Hollywood's film directors: Come back with a signed agreement with the Producers Association by eight o' clock tonight, or we'll boycott the Academy and call a strike. I'm here for an answer, not for more stalling."

"Mr. Capra," called out Joe Schenck, "we are not stalling, just procrastinating. Wait in my outside office, please. And maybe we can procrastinate something out of this."

Capra retreated to the outer office, where he twisted his hat for the next two hours. "I knew Schenck was never more dangerous than when he was amusing," he recounted. Up until that point, a number of things had made an agreement between the two sides particularly difficult to reach. One had been the Guild's decision in 1937 to admit assistant directors and unit managers into its ranks as so-called Junior Members of the Guild. This was done partly to help define and enhance the professional status of these key members of the directorial team, and to secure for them basic minimum salaries and benefits - and partly to swell the size and negotiating clout of the SDG, which within a few months of that decision grew to some 550 members.

A second complicating factor had been the evolving role of the National Labor Relations Board, created in 1935 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt under the Wagner Act, in deciding matters concerning the right of employees to engage in collective bargaining. The Wagner Act helped other Hollywood guilds gain momentum, including the Screen Actors and the Writers. It also held sway in any number of other fields of employment.

In 1937, the NLRB had ruled that automobile design workers at the Chrysler plant in Detroit did not qualify for protection under the Wagner Act because they had supervisory powers (most notably, the ability to hire and fire other employees). Out in Hollywood, the Producers Association immediately used the ruling as a wedge to try to diminish the ranks of the Directors Guild. It contended that assistant directors and unit production managers were not management personnel and that the SDG should be allowed to negotiate on behalf of only directors, not their subordinates.

But SDG negotiating committee member Howard Hawks and Guild attorney Barry Brannen pointed out that the studios, not the directors, had contractual power over ADs and unit managers, therefore the ruling did not apply. The Guild refused to divide its membership. It petitioned the NLRB for certification as a bargaining agent.

NLRB hearings on the matter began in late August 1938. As they drew to a close in October, the Producers Association, surmising that the government would almost certainly support the directors' right to organize, took preemptive action. Goldwyn approached Capra with a proposal for breaking the impasse, and promised that producers would appoint a new negotiating committee to work out the details in private. Capra, who later cited his "great respect for Sam Goldwyn's integrity" as well as admitting his own yen to go "mano-a-mano" with Schenck, agreed. The Guild called off the NLRB hearings, and prepared once again to negotiate.

Several months later, in early February 1939, the producers got around to appointing a new negotiating committee, and to calling that fateful meeting with directors. That was when they asserted all over again that they would not proceed unless the SDG threw the assistant directors out of the Guild. And that was when the directors decided they had had enough. At 6 p.m. Friday, Feb. 17, as Capra recalls it, Schenck at last opened the door of his office and handed him a two-page letter of agreement.

It was addressed to Capra and signed by Schenck, and it was all there: recognition of the SDG as sole bargaining agent, inclusion of the assistant directors, agreement to an 80 percent Guild shop, and concurrence on conciliation and bargaining procedures. According to Joseph McBride's account of these events in his Capra biography, The Catastrophe of Success, all that remained was to establish minimum editing periods for directors, and the floor on salaries and working conditions for assistant directors. The one caveat was that unit managers would be dropped from the Guild after a separate contract for them had been negotiated.

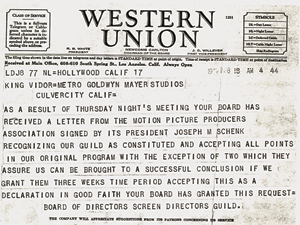

Telegram to King Vidor from the board announcing that the producers

Telegram to King Vidor from the board announcing that the producers

had finally agreed to accept the Guild. (Credit: AMPAS)

"Is this OK?" asked Schenck.

"It's very OK," replied Capra. "There will be no Academy boycott, and no strike, and you're looking at a very happy man."

"I'm happy too," said Schenck. "You can make me happier if you'll answer one question: Were you bluffing?"

"What really matters is that you thought I was not," answered Capra.

Capra then brought the agreement to a waiting SDG board, and as he tells it, they all went out and got "spifflicated."

The next day a Western Union telegram went out to King Vidor, founding president of the Guild, at MGM. "Your board has received a letter from the Motion Picture Producers Association, signed by its president Joseph M. Schenck, recognizing our Guild as constituted, and accepting all points in our original program, with the exception of two which they assure us can be brought to a successful conclusion if we grant them three weeks time period.

Accepting this as a declaration in good faith, your board has granted this request," it said. It was signed by the SDG board of directors. The Guild's long struggle had laid the foundation for the directors' creative rights and for a significant part of the American motion picture business as we know it.

As Variety summarized in a lengthy piece on the history of the Guild on the occasion of its 50th anniversary, directors were contractually guaranteed the right to be consulted concerning the cutting of their films, and to be consulted regarding the employment of principals before assignments were made. They won the right to two weeks' preparation time for films with budgets more than $200,000, and five days' preparation time for films budgeted at less than $200,000. Minimum salaries for assistant directors and second assistant directors were established, as were minimums for unit managers, though these were soon spun off into a separate Guild of their own. (UPMs merged with the Directors Guild in 1964.)

As for the Academy Awards banquet of 1939, the show did go on. As he stepped to the podium that night at the Biltmore Hotel, Capra recalled, "I never felt prouder, or more grateful, for being the head of this beloved Academy which, only days ago, I had conspired to disrupt."

And though he claims it was the last thing he expected, Capra was named best director of the year for You Can't Take It with You. The film itself was named best picture. That May, Capra was re-elected president of the Guild, and the membership ratified terms of its new contract. And in the final days of 1941, Schenck offered Capra the richest contract the director had ever seen to come to work at 20th Century Fox. Capra didn't accept it. Instead, he enlisted in the Army.

But that's another story.