BY STEVE POND

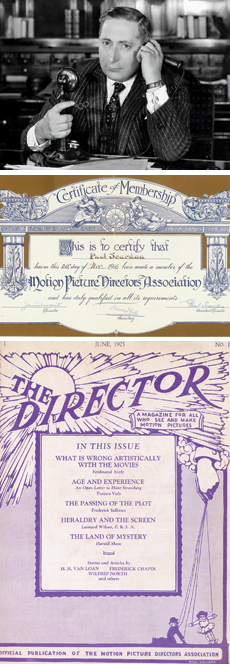

BAND OF DIRECTORS: Mostly a fraternal organization, the Motion Picture

BAND OF DIRECTORS: Mostly a fraternal organization, the Motion Picture

Directors Association celebrates "King Vidor Night" in 1923. (Credit: AMPAS)

The Directors Guild of America, according to most accounts, was born out of a December 1935 meeting at King Vidor’s house, where more than a dozen directors got together, chipped in $100 each, and formed an organization that was initially called the Screen Directors Guild. But that’s not when things really started. To understand where those directors were coming from, how they formed a guild - and, even more important, why they formed a guild - it's necessary to back up a couple of decades. The seeds were sown in the weeks and months leading up to that 1935 meeting, but also in the years and decades before that, and in the labor struggles sweeping the United States during and before the Great Depression. Back then, two decades before the guild was born, the job of director was still being defined.

J. Searle Dawley, who called himself the first motion picture director because he was hired by the Edison Manufacturing Company to helm The Nine Lives of a Cat in 1907, said, “the cameraman was in full charge” before that. The auteur theory was decades off - and while some directors may have acquired power and exercised creative control in those early days, many others were employees who worked at the whim of producers and studio chiefs. At times, the studios would give a director his next assignment only a few days before a movie would start shooting, excluding him (or, in rare cases, her) from virtually the entirety of preproduction. Often, a second unit would shoot simultaneously, with another director handling those chores and reporting not to the first director, but to the studio. Sometimes, the job simply entailed getting the shots that the studio wanted, with little or no room for creative input. And the editing process, often as not, would be handled by the studio, not the director.

“In the eyes of the public, as well as of their co-workers, they were associated with management and, like the stars, they were relatively highly paid,” wrote Louis B. Perry and Richard S. Perry in A History of the Los Angeles Labor Movement, 1911-1941. "But... they had little [creative] control and, though they worked closely with producers, in the final analysis they were subject to the latter’s dictates." Even as late as 1939, producer David O. Selznick summed up the prevailing vision that seemed to be handed down since the early days of the industry: “The director, nine times out of ten, is... purely a cog in the machine.” In 1915, the cogs decided to get together. But when the Motion Picture Directors Association was founded that June, the creative rights of directors were barely addressed in the organization’s charter.

It was a time of growth for unions across the country, but Los Angeles, the home of the movie business, was a tougher market for organized labor. Anti-labor sentiment grew markedly after the 1910 bombing of the Los Angeles Times building, an action widely blamed on labor activists. So when the American Federation of Labor (AFL) set its sights on Hollywood craftspeople, the studios responded by creating several organizations that united producers and studios to work against the AFL’s push to create closed shops: The Motion Picture Producers Association was the first, with the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (an MPAA precursor) and the Association of Motion Picture Producers following.

In this climate, a group of directors met quietly in 1915 and formed the Motion Picture Directors Association. It wasn’t a guild or union, and directly lobbying the studios for more control wasn’t on the agenda. Though early records of the MPDA are scarce, the notes of its secretary, Dawley, describe it as a “secret society” whose “rules and rituals were formulated, often somewhat the rules of the Mason.”

Of course there was more to it than that. The four stated goals of the MPDA were to “maintain the honor and dignity of motion picture directors,” “to... exert every influence to improve the moral, social and intellectual stand of all persons concerned with the motion picture producing business,” “to cultivate social intercourse among its members,” and “to aid and assist all worthy distressed members... their wives, widows and orphans.” More specifically, the MPDA set out to curb the producers’ casting couch. A key aim, wrote Dawley, was “to try helping each other and to endeavor to clean up the [motion picture] business from the habit of exporting girls who are weak on the side of resisting flattering offers by certain executives of the... business... Directors were often forced to use girls in their art whose only qualifications was that of being a friend of so-and-so.”

The moral outrage went further than that too: Another founding member, Charles Giblyn, described the initial meeting as “indignant” and said the general public thought of studios as “habitats of criminals and vagrants.”

In a 1918 article in The Exhibitor’s Trade Review, he also said that directors needed to organize in order to stop one another from trying to sabotage rival productions. “The MPDA became the first vehicle to present directors as a single power,” wrote Lisa Mitchell in the DGA Magazine in 2001. “By their formal unification, members established the importance of their new profession and could speak with one voice within the film industry and beyond.” Still, the organization did not appear to have used that single voice for bargaining. In an interview conducted for the DGA’s oral history series in 1980, MPDA co-founder King Vidor said the group “seemed to be more social, it didn’t suggest labor or group bargaining in any way.”

Around the country, though, the labor movement heated up at the conclusion of World War I. In 1919, according to Robert Zieger in American Workers, American Unions, approximately 3,000 strikes took place involving 4 million workers, more than 20 percent of the American workforce. And in Hollywood, some unions were growing more militant. In 1918, according to Gerald Horne’s Class Struggle in Hollywood, a strike by 500 workers forced several productions to shut down. The studios finally cracked down in 1921 and locked out the craft unions, although five years later the AFL had a breakthrough of sorts, negotiating a basic agreement with the studios on behalf of stagehands and other craftsmen. But the writers stayed out of the fray: Although they formed the Screen Writers Guild in 1921, that organization was initially fraternal and wasn’t incorporated as a union for a dozen years.

Around the country, though, the labor movement heated up at the conclusion of World War I. In 1919, according to Robert Zieger in American Workers, American Unions, approximately 3,000 strikes took place involving 4 million workers, more than 20 percent of the American workforce. And in Hollywood, some unions were growing more militant. In 1918, according to Gerald Horne’s Class Struggle in Hollywood, a strike by 500 workers forced several productions to shut down. The studios finally cracked down in 1921 and locked out the craft unions, although five years later the AFL had a breakthrough of sorts, negotiating a basic agreement with the studios on behalf of stagehands and other craftsmen. But the writers stayed out of the fray: Although they formed the Screen Writers Guild in 1921, that organization was initially fraternal and wasn’t incorporated as a union for a dozen years.

The MPDA, meanwhile, continued on its own path. “Meetings... are a clearinghouse for discussion of new methods, of business and art problems, of ways and means and for sifting the wheat of value from the chaff of ‘bunk’ in production,” wrote MPDA secretary Ashley Miller in 1919. Part gentleman’s club, part think tank and part quiet lobbying organization, the MPDA added a New York branch, fought “blue laws,” argued for a stop to overseas production, and got involved in the discussion over the regulation of movie content in the wake of a series of high-profile Hollywood scandals. One of those scandals involved MPDA president and founding member William Desmond Taylor, who was shot and killed in his Los Angeles home in 1922, in a still-unsolved case that stirred up whispers of salacious behavior. The organization was aware of its potential as a bargaining agent for directors, but according to other notes made by Dawley at the time, it opted not to join the labor movement when an AFL representative came calling. “The [motion picture] business was watching every move we made,” Dawley wrote. “We were a very strong organization if we really wanted to use the power for we had nearly every director in the business that amounted to anything as a member.” When the AFL rep spoke to the MPDA, he wrote, the directors thought his pitch was oriented too much toward the financial side, and not enough toward the creative. “We were not joined together to fight the MP business,” Dawley insisted. “Our idea was to be of some service to the MP art.”

The MPDA turned down the AFL’s offer. The MPDA, which grew to between 100 and 200 members, also published a journal called The Director (later The Motion Picture Director) from 1924 to 1927. One of the articles in that publication indicated just how far the image of the director had come: “Of the many artists who help to make up the finished film none is more important than the director,” wrote Louis B. Mayer. “When a picture is screened it is largely a reflection of the mind that directed it.”

But if Mayer was generous with flattery, he was also instrumental in the creation of an organization that hastened the decline of the MPDA: the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Mayer and other studio chiefs formed the Academy in 1927, in part because of the threat of more widespread unionization; as directors, writers and actors joined those branches of AMPAS, the power of their individual organizations waned.

In addition, part of the Academy’s goal was to mediate in labor disputes - but not surprisingly, given the men at the top, it generally came down on whatever side the studios wanted. By the time most of the members of the MPDA joined the directors branch of the Academy in the late ’20s, the MPDA had essentially become defunct - aided, Dawley said, by studio resistance that killed a proposed filmmakers collective with which the directors would finance their own films outside the studio system. The Academy, wrote The Hollywood Reporter in a 2005 article, “contributed to an unprecedented era of management-labor cooperation - but it also kept actors, writers and directors from forming unions.”

A remark attributed to Dorothy Parker, and quoted by Nancy Lynn Schwartz in The Hollywood Writers’ Wars, summed it up more colorfully: “Looking to the Academy for representation was like trying to get laid in your mother’s house. Somebody was always in the parlor, watching.”

At the dawn of the 1930s, sound had taken over the movie industry, and some directors found that the power they had worked to acquire was waning. “The concept of authorial freedom as it is understood today did not exist in Hollywood during the ’30s,” wrote Tino Balio in Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise. With the growth of the power of the studio system, even directors who had been given artistic freedom found the purse strings tightening and the restrictions increasing. “A lot of directors were underpaid,” Rouben Mamoulian said in an interview conducted for the DGA’s 50th anniversary, “and being underpaid also meant that they lacked authority in many fields [where] the director should have authority.” King Vidor, for example, had to personally finance Our Daily Bread in 1934 - because, he wrote in his autobiography A Tree Is a Tree, “all the major companies were afraid to make a film without glamour.” (The film, somewhat prophetically, was about a group of struggling workers who form a collective.)

Even the most powerful directors began to have their authority questioned. Lewis Milestone was sued by Warner Bros. when he left the studio over its practice of loaning him out to other studios and pocketing most of the money themselves. John Ford was challenged over casting and rejected by five studios when he tried to get a political film, The Informer, off the ground in 1934. Ford, who had long advocated that directors organize, was blunt: “Changes are due in the motion picture industry from the director’s standpoint,” he declared. But every attempted change met with resistance. Cecil B. DeMille had tried to make a move three years earlier, enlisting Vidor, Milestone and Frank Borzage to set up an organization he planned to call the Directors Guild. According to Robert S. Birchard’s book Cecil B. DeMille’s Hollywood, he approached the head of sales for Paramount to get support for the plan, in which the directors would make independent films and distribute them to independent movie theaters. In the rocky economic climate of the times, it proved impossible for DeMille to secure financing; the company never got off the ground and its manifesto, a “Directors Declaration of Independence,” never adopted.

As some directors lobbied for collective action and others dared not buck the studios, other industry workers found progress tough as well. In 1931, the Assistant Directors Union tried to gain recognition from the studios, institute collective bargaining and improve conditions; its efforts were rebuffed. When electricians called a strike two years later, the studios hired scabs. Those who worked for the studios, a Warner Bros. executive said in an oral history at UCLA, were “exploited en masse,” with long hours, low pay and no job security. Wrote Gerald Horne, “creative types who had to dig deep into their psyches to tap their muse were driven further into psychological turmoil by the instability of the industry in which they toiled.”

The studios, meanwhile, faced bigger problems than striking stagehands. Paramount and RKO both went into receivership in January 1933, driven to bankruptcy by over-aggressive expansion in turbulent financial times. On the heels of President Roosevelt’s enforced bank holiday in 1933, MGM, Paramount, Columbia and Warner Bros. used that drastic measure as an inspiration for their own dramatic step, announcing across-the-board salary cuts of as much as 50 percent for anyone making more than $50 a week. The Academy supported the plan, further angering both above and below-the-line workers - and in a subsequent meeting at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, King Vidor wrote, studio bosses made it clear that “anyone who got up and objected to... taking this cut was fired.” Although the pay cut would be watered down and only lasted for eight weeks, it also set in motion a wave of unionization. The Writers Guild was formed in April 1933, followed two months later by the Screen Actors Guild. The directors were slower to organize, but their intention was clear from that night at the Roosevelt when, said Vidor, an impromptu meeting of several directors on the sidewalk outside the hotel made the course of action clear: “It was just bluntly stated, ‘We must have a guild to speak, and not the individual that can be hurt by standing up for his rights.’”

And this time, Congress was strengthening the hand of workers who wanted to organize, even as the studios refused to negotiate with the new guilds. In June 1933, the National Industrial Recovery Act granted unions the right to collective bargaining. Under the Code of Fair Competition for the Motion Picture Industry, the studios finally agreed to allow unions later that year, but those same studios then refused to recognize or negotiate with the unions. Their resistance would last for a few more years, but it was doomed. Teamsters, farmers, mine workers and autoworkers went on strike all across the country in the ensuing years, while the formation of the National Labor Relations Board in 1935 dealt another blow to industries that wanted to ignore unions.

The studios acquiesced as thousands of crew members joined IATSE, though anti-union activists made much hay out of charges that Hollywood’s union labor was rife with Communists. And then, at the end of 1935, on the heels of a Paramount edict that its contract directors would be fired if they didn’t accept the pictures that were assigned to them, 13 directors met at Vidor’s house. The Screen Directors Guild was born, and that’s where the next chapter of this story begins.

For the next part of the story, see "A Guild Is Born", written by Pond for the 70th anniversary issue of the Quarterly.