BY KENNETH TURAN

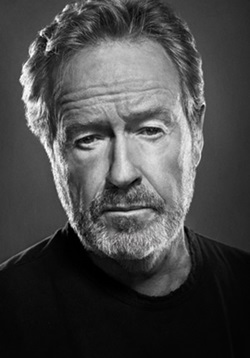

Photographed by Scott Council

The trajectory of a director's career can sometimes be as compelling as the films he or she has made, and so it is with Ridley Scott.

The trajectory of a director's career can sometimes be as compelling as the films he or she has made, and so it is with Ridley Scott.

At age 40, after years of impressive work directing commercials, Scott began to realize his lifelong dream of feature filmmaking with The Duellists in 1977. However, he was considered by some to be a bit of an interloper, someone not to the manner born.

Cut to 30-plus years later. After delivering more than 20 features, including three films—Thelma & Louise, Gladiator, and Black Hawk Down—that earned both DGA and Oscar best director nominations, Scott is more than accepted. He is widely respected as someone whose exceptional visual sense and gift for making out-of-the-ordinary worlds come alive on screen has made him the last master of traditional, old-school epic filmmaking.

His movies may be classic, but the West Hollywood offices of Scott Free, the production company he runs with his brother Tony, are coolly modern. An entire wall of the conference room, where Scott arrives to be interviewed, is filled with candid photographs of both he and Tony on the various sets they have dominated on locations throughout the world.

Despite his no-nonsense, master and commander reputation ("Nothing stops him, nothing," says producer Brian Grazer), there is no hint of bluster or bravado about Scott in person. Yes, he is direct and sure of himself, but his manner in conversation is low-key and reflective, his air more companionable than commanding.

What he says can be similarly surprising, such as attributing his tolerance for stress to growing up with a mother who was "the master stresser." He's never had any doubt that he was born to direct films and he's happy to have reached the point where the world agrees.

KENNETH TURAN: Is it true that watching films as a young boy made you think about the possibility of directing and getting involved in the business?

RIDLEY SCOTT: Yes, but that was a secret. I thought it would be too silly to suggest to my parents that I wanted to be a film director. Because in the north of England, the part of the world where I came from, that would be unthinkable. The film industry and theater and all that stuff was the other side of the moon. And so I figured I wouldn't even dare try acting, although I thought about that as well. That was just too silly for words, I wouldn't dare. But at school, even at like 7 or 8 years old, if there was some kind of play, like a nativity play, I'd always get very involved. And though I totally enjoyed it, I never really thought there was any road ahead.

Q: Do you remember specific films that captured your imagination when you were growing up?

A: Well, my mum was a filmgoer, she would say, 'We're going to the pictures this afternoon,' and she'd take me with her. And I started to pay attention. The very first film I ever saw was a pirate movie called The Black Swan with Tyrone Power. And I thought that was great stuff. Of course, in those days Technicolor was really Technicolor, there was no such thing as desaturation. Everybody looked super suntanned. The first film that gonged me was a movie with Rita Hayworth, Gilda, which I was way too young to see. When she sang, 'Put the Blame on Mame,' something funny happened to me. I think I was about 7, but I definitely got the urge. I realized there was something special about Rita.

Q: But weren't you also interested in art?

A: My one real talent from a very early age was that I was able to draw pretty well, that was a constant. I was doing oils by the time I was like 8 or 9. I was one of those kids who tended to stay in on Saturday nights. My mother used to come and say, 'Why don't you go to the dance with the boys?' And I'm going, 'No, I'm perfectly happy.' I think my parents thought I was definitely weird. But I hated school. Then some bright art master told me, 'What the hell are you staying here for? I'll line up an art school for you,' and that was the best advice I ever got in my life. As soon as I entered art school, it was like the sun rose, right? After that I got into the Royal College of Art, which is without any question the best art school in England, if not the world.

Q: So the Royal College is where you made your first short film, Boy and Bicycle.

A: There was no film school there; all there was was a Bolex camera with a windup key in a cupboard with a light meter and instruction book. That was it, that was the only indication that they were even trying to be a film school. I wrote a script and they said, 'Okay, you've got the camera for six weeks.' So in the summer holidays I went back home, and I fundamentally ruined my brother Tony's holiday by hauling him out of bed at 5 or 6 o'clock in the morning and saying, 'Come on, I've got the car, let's get going.' He played the boy on the bicycle. We'd drive up to Hartlepool with the gear that I'd manage to rent at 12 pounds a week. Arriflex legs, no-battery stuff because it was all like winding a clock. The whole film cost 60 quid.

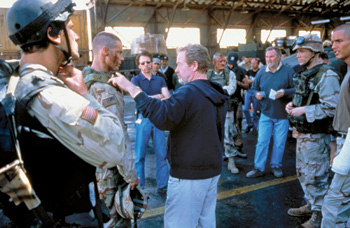

Scott knew Black Hawk Down "had to be dusty, had to be in the streets."

Scott knew Black Hawk Down "had to be dusty, had to be in the streets."

Q: Did you have any idea what you were doing?

A: It was a self-taught process, I learned with my brother. In those days we'd be standing there smoking Woodbines. I was bitten by the bug of saying, 'Right, Tony, shut up complaining, ready, ready, action! Next time go stand back over there. Shut up. Okay. By the way, go and get lunch while I think about what I'm going to do.' So I'd give him money to go and get sandwiches. That's what it was.

Q: Then you went from art school to the BBC as a set designer. What were you thinking there?

A: I figured, I don't know how I'm going to be a director. I don't know how I'm going to get to talk to actors, because drama school's a long way off. And therefore, if I design the cubicles where everything goes on, if I design the proscenium, at least that's close, that's the next best step. And by the way, it's great. I love designing, and I still do it. The BBC was also a good lesson in learning how to deal with bureaucracy. That's something art school never teaches, or film school or university. Working teaches you how to deal with people. Suddenly I had an assistant who was pissed that this newcomer just came straight in. And I felt it; I was sensitive to his feelings. And I was given series and plays immediately. Of course, being new and inexperienced, I was always moving the fuckin' props and driving the director crazy. Because in TV, if you put a plant here and plan to do dialogue after lunch, I'd come in during lunch and I'd move it there. So the director would say, 'Action, Boom'—and live, somebody's got a plant in front of his face.

Q: How did you get comfortable with actors?

A: I was able to do some television directing for the BBC, some episodes of Z Cars, and it was awful at first. Because I tended to inherently talk about the visual aspect: 'You'll come in here, go there, sit down, talk.' And the actor would ask, 'But what am I?' And I'd say, 'Oh yeah. I think you're bad tempered.' Then I did a few episodes of a series with a great actor called Ian Hendry, who would watch me and, knowing that I wasn't trained, would talk to me.

Q: What did he say?

A: He'd say, 'Your voice is too quiet. You're too apologetic. Take no prisoners. Apologize for nothing. And be assertive. Above all things, any decision is better than no decision.' And from that moment on, I just changed gear. And I took myself back to how I talked to my brother in the mornings on Boy and Bicycle when I'd say to him, 'You know something, you're not sad enough.' And he'd say, 'Why am I not sad enough?' And so I'd talk to my brother. And I thought, 'You know what? That's how I've got to talk to actors.' So I learned engagement with an actor, where you assume partnership. It's not Svengali, it's a partnership. The best results are with partnership. If the actor says, 'But...,' you learn to listen. See? It's a good idea. Then they love the fact you accept them.

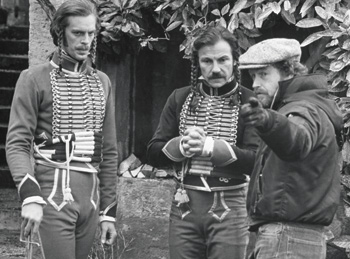

FIRST BLOOD: (above) Scott got Paramount to invest $800,000

FIRST BLOOD: (above) Scott got Paramount to invest $800,000

and went to France with Keith Carradine and Harvey Keitel

to direct his first feature, The Duellists.

Q: I imagine you've got that kind of relationship with Russell Crowe, whom you've worked with five times.

A: Constant discussion. Constant. From stage one, even when I think I've got a good screenplay, invariably, Russell thinks it's no good, that the screenplay is terrible. So then we've got to sit there and go right through it. And then I realize, actually, he really means a third of it, or maybe 20 percent, is no good. And the other 80 percent is quite good. And so we talk, talk, talk. It's a build. That's rare though. To get that kind of relationship with an actor is rare.

Q: You've said directing commercials was your film school and that one of the things it taught you was how to work fast.

A: Fast and on the clock. There's a clock going tick tick tick, and that's costing you. And then at the end of the day you have the agency tut-tutting on the side, so they're the studio. The agency is the pressure of the studio; they're always trying to intervene and say, 'Why do you want to...?' I learned to deal with that by saying, 'Good idea.' If you say, 'Good idea,' you've just defused the bomb. So I learned all my politics from advertising and walking the tightrope. Because film is walking the tightrope.

Q: Between art and commerce?

A: Art and commerce. I'm still very reasonable; I come in under budget. We were $15 million under on Robin Hood. Anyone giving me that much money to spend on my intuition and whim deserves respect, they deserve to be listened to. If I was an investor, I'd want to have a say as well. I think at the end of the day, filmmaking is a team, but eventually there's got to be a captain. Therefore, that will finally boil down to saying, 'Let's do this, we're going to go this way. No more talk, we're going to do that.'

Q: How do you stay on top of the film you're shooting?

A: For one thing, I use a car and driver. I would never drive myself to and from a shoot because I'm so distracted. I like to sit in the back with my boards going over what I'm doing that day. I'm very orderly and I've had a bit of practice. For instance, every lunchtime during shooting, I would go to my trailer and a sign would go on the door: Do Not Disturb. I'd eat in eight minutes and nap for forty, then you're recharged. So I love to do that. Now we've moved to what I call French hours where we don't do lunch. The upside is you don't lose the two hours midday where people eat too much and the first hour back they're sleepy, and then by the time they're waking up, it's like 3:30 in the afternoon. What I do is, I'll say have a good breakfast, eat on the run, and I have to wrap at 6, that's it. So I'd wrap and half the time I'm driving home at night in the best light, which would drive me crazy. But we got through it.

ACTION: Scott with a bloody

ACTION: Scott with a bloody

Harrison Ford in Blade Runner.

Q: Being organized seems like second nature to you. That must help on a film like American Gangster (2007) where you're doing 50 setups a day.

A: More on Black Hawk Down. But there I had 11 cameras. So sometimes there's 100 or more setups a day. And what I discovered is that the actors love it; they love to move fast. You'd think actors would say, 'I must have my rehearsal,' and 30 takes later they'd say, 'I have the take.' It doesn't work that way. I've always heard that Clint Eastwood does two takes and says, 'That's it.' And I always like to do that. With Russell, he knows I'm already thinking, 'This is pretty good,' so he'll put his hand up and go, 'One more?' I'll say, 'Keep running.' It's faster to keep running than to explain why. You have to remove your ego as a director; let others have ego. In the final analysis, your ego is the quality of the movie.

Q: As a commercial director, you've operated your own camera. Do you miss doing that on features?

A: Oh yes, sure. I've operated on 2,500 commercials, from Morocco to Hong Kong to wherever. On cranes, dollies, handheld and all that. I operated all of The Duellists, all of Alien, all of Legend—I wasn't allowed to on Blade Runner. You're painting when you're operating. The proscenium, which is the viewfinder, is where the bells go off. If you're the actor, I'm actually engaging with you, I'm looking right inside you, and I'm seeing every goddamn blink. They like that. It's a bit like being a good still photographer. And then they blossom. They blossom.

Q: Why don't you still do it?

A: I can no longer operate successfully because I've got three, five or 11 cameras working. Better for me to be sitting in the tent going, right, action and looking at the video assists. Boom, boom, boom—I'm looking at the cut and I'm saying, 'Pete, you're too wide, change your lens, move in, and let's go again, that was slow.' Because if I'm operating and I've got five other cameras, I've got to come back, go to the tent, look at everything—I just added 20 minutes to each setup. So it becomes practicality.

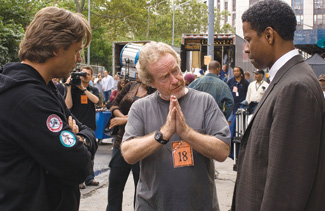

Russell Crowe and Denzel Washington in American Gangster.

Russell Crowe and Denzel Washington in American Gangster.

Q: The Duellists (1977) was your first feature. How did you finally make it happen?

A: Because I did the commercials, I was making money and was able to buy Gerald Vaughan-Hughes' very good screenplay of Joseph Conrad's The Duellists and off that, one way or another, I was able to pay for my own travel and finally persuade Paramount to kick in $800,000. And then we went off to France and it was the worst time of the year with the rain. But it was perfect for the film because it was all drizzling.

Q: That wasn't your basic Hollywood movie. What did the studio think of it?

A: When I came to Hollywood with [producer] David Puttnam and the finished film, I called Paramount and there was a lot of whispering in the background. I think they'd forgotten I was making a movie, I swear to God. No one from the studio came when I was in France for whatever, seven months. I said to David, 'Is this normal?' He said, 'Not really, but count your lucky stars, just leave well alone, because we're kind of enjoying the creative freedom.' So I come in to screen it and they were taken aback. The guy who was knocked out, funny enough, was Barry Diller. He was in the room and went, 'Oh wow, I didn't realize we were making this. Come and see me tomorrow and let's discuss what you want to do next,' which is a good start. And I talked to him in detail about how I wanted to go back and do Tristan & Isolde. And that afternoon, Puttnam said, 'Hey, there's a film on at the Egyptian Theatre. The only time we can get in is about 2 o'clock, it's called Star Wars.'

Q: What was that screening like?

A: I go to this place called The Egyptian where I'd never been before in my life, and I had never experienced a thrill like that. It was like a Super Bowl. There are queues around the block, the theater is jammed, and the room is like aaaah in anticipation. And when it comes on, I'm thinking, what am I doing? After seeing Star Wars, I backed off doing Tristan & Isolde, and about three months later I was offered this thing called Alien. And I went, I'll do it. And because I'd been interested in all these European comic strips from Heavy Metal magazine, I thought, I know how to do this, I'll do it. And I was the fifth choice.

Q: Did you have much interest in science fiction before that?

A: I'd been kind of enamored of the visual effects in The Day the Earth Stood Still, and when 2001 came out I took an afternoon off and walked down to a theater and saw it in 70 mm. I was completely by myself, there was no one there. And I watched it thinking, holy shit! He just crossed me into the zone. This feels so real and so logical and so clever and magical. But aside from that, science fiction was always Them and It and something out of the bog and all that shit. I thought they were vaguely aligned to bad sex movies, vaguely not nice to watch.

Nicolas Cage in Matchstick Men.

Nicolas Cage in Matchstick Men.

Q: That great shot in Alien (1979), when the monster erupts out of John Hurt's stomach, how did you do that?

A: It was basically a glove puppet. [Designer] Roger Dicken walked in with it in a bag under his arm, because I didn't want anyone to see the alien. In the scene John Hurt is having his breakfast and chokes and they flop him onto the table. I had a chest made out of fiberglass with a hole in the middle and a T-shirt on it, and I screwed it to the table. John was there with his head pushed up with rubber cushions behind him, and at some point Roger, lying in his lap, was supposed to push the puppet through the hole.

Q: Seriously?

A: Believe me, it's pretty basic. Roger goes wham, and the T-shirt doesn't go. And I'm saying, 'Cut Cut Cut,' because I've got air lines with pipes everywhere to shoot blood all over the cast. It's five cameras and one shot. One take. That's it. And I have one camera above and I said, make sure no pipe hits the camera, that's the key. Because I can always shoot reactions again, but the blood, I'm not going to do that again. And then I go in and I have to slit the T-shirt on the surface with a razor blade. And John's lying there going, 'Come on, mate.' He's drinking white wine, so I give him a drink to keep him calm. I go again and it was historical. I've got all the continuity books of that, every page has got Polaroids of what's going on, plus all the handwritten line changes, and there's blood all over the scripts. These are incredible documents.

Q: Let's talk about Blade Runner (1982). The look of it, the setting and the detail, was remarkable. Where did it come from?

A: I think that's from my old art directing days. There were a number of years when I would be flown into New York on a monthly basis, shooting television commercials, fashion, things like that. And New York to me always seemed to be a city on overload, particularly in the late '60s, early '70s. In those days, the grim reality was it was dark, dingy and smelly. And I liked it because it was dark, dingy and smelly. I liked the pulse of Manhattan, and I never forgot that. I also shot several times in Hong Kong in the early '70s. There would be fleets of junks locked together for the night and I'd walk across them. I'd knock on the rail with the police and the guy would ask, 'Can we cross your deck because we want to go out to the end junk?' All the families are cooking on the decks on open fires, it was like the 19th century. And I have always remembered that. And then at the same time, you've got the biggest building in the world going up, the first of the big towers in Hong Kong. And alongside it was a snake butcher, this shop where they sold snakes to eat. So when I started to do Blade Runner, I thought it's got to be a city like that.

Q: By all accounts, Blade Runner was a difficult shoot.

A: At that point I'd done two movies, but that was in France and London. Now I'm here in Hollywood and no one really pays attention. I'm the new kid on the block, and I'm not a kid. I'm super experienced, more than most first-film directors ever, okay? And I'm walking in the door with probably one of the best scripts in town. It's taken me seven or eight months working with [writer] Hampton Fancher on a day-by-day basis, where his really good screenplay, which was set in an apartment, gradually grew. I said, the opportunity here is so great, it's got to go outdoors. If it goes out the door, the world outside has to support it. So I began but none of this team was mine at all. I couldn't choose my team because I was suddenly not on home ground. I'm standing there staring and being questioned constantly. Which is okay, because then I have to really bite the bullet from the days at BBC when I learned 'Don't lose it, be tactful, don't kick holes in doors.' So that's why it got feisty. And was I feisty? You'd fuckin' better believe it. Because I knew way back when, if you want it, you have to go for it. And I wanted it, and I went for it. And that's why I think I became marginally unpopular. But by then, I didn't give a shit, frankly, because the end result was everything. And the end result was correct.

Q: Blade Runner is enormously respected today, but when it came out it was a different story. Are there things about your work that you think people don't appreciate enough?

A: Are you asking do I care?

Q: That's a good question. Do you care?

A: I think deep down, yes, you do. Everyone wants a little bit of—acclaim's the wrong word—just a little bit of appreciation for something that goes very well. Because it's so hard to make movies. I always remember I was thrashed for Blade Runner. I couldn't believe it. I thought, wow. And it was a big lesson then because I thought, you know what? It's like in athletics. Just when you think you've got it, you don't. You must always remember that. You've never quite got it. That's important. Just when you think you're going to win, you're not.

Crowe in Gladiator.

Crowe in Gladiator.

Q: I want to ask you about Thelma & Louise (1991). That seemed like a different kind of picture for you.

A: Oh, yes. I want to change gear constantly. That's why I do films like Matchstick Men or A Good Year. So what I'm doing right now, I'm going to do the Alien prequel, but what I really want to do is Gucci, the story of the Gucci family. Fantastic. You've got to keep yourself guessing. Art's like a shark, dude. If it stops swimming, it drowns. So I like to put myself in places of insecurity. It's learning to trust your judgment. I'm now full-bore intuitive. You have to be. I can't keep asking, what do you think?

Q: I gather there was a discussion with your producer Alan Ladd about the ending of Thelma & Louise.

A: After three films [for the Ladd Company], Laddy would finally talk to me. He said, 'What do you think about the ending?' I said, 'I think the ending's perfect' He said, 'You can't think of anything else?' I said, 'No.' He said, 'Nor can I, let's do it.' So I said, 'What else are you going to do? Have them arrested and put away for the rest of their lives? That's depressing. If I take them off the cliff, they've got that kind of nice song, they continue the journey. But you have to freeze it there. You can't see the rest.' That was fun.

Q: I want to jump ahead to Gladiator (2000). Is it true that you decided to do the film after seeing the famous Jean-Léon Gérôme painting of a victorious Gladiator?

A: Totally. With respect to everyone who wrote the script, it wasn't that [that made me want to do it]. Walter Parkes said, 'Before you read the script, perhaps you'd better see this. This is what it is.' And I saw the painting and went, 'Damn, I'll do it.' And he said, 'You will?' I said, 'Yes.' 'But you haven't read the script.' I said, 'I don't care, I know what to do.' I think that was the briefest conversation I've ever had about a project. I know a lot of people were sniggering because they thought it was a sword and sandal movie, but we drove forward, literally sailing into the wind, with a screenplay that had to be written as we went along. I knew what to do for the first three weeks, and then after that I was writing every night.

Q: That's your intuition again.

A: Intuition is everything for me. And learning to trust it and listen to your inner voice can only come through experience. If I'm directing, I'll be sitting there on the weekend thinking, 'How do I start the fuckin' movie?' And I'm going around and then I'll get a ding and I'll stop there—like one finger on the Olivetti, but I draw. I start my storyboard. As soon as I've got the first picture on the board, I've already got the page in my head. Voom. It's like a typewriter, but you're evolving on a visual level. And picture is very closely tied to words, which sometimes means talking heads are fine. That's a visual decision. I don't want to upstage what I'll be doing by having a tracking camera and cranes and shit because I've got two great actors talking to each other across the table. Leave it. Let it be.

Q: I understand you often use a two-camera V setup to film conversations, is that right?

A: Sure, Sure. I learned that from TV, to save the actors. Say I'm doing a scene with you right now and Dustin Hoffman is off-camera, just feeding you the line. As the director I'll say, 'Help him but save yourself, don't shoot your wad.' And the actors will say, 'No, no, I won't,' but they do. So by the time I've finished a number of takes this way and turn around and relight it, the actor is weary, he's shot. If you do it together, it's just a lighting question.

Scott and company create the monster for Alien.

Scott and company create the monster for Alien.

Q: One of the most impressive things about Black Hawk Down (2001) is how intense the level of reality is. How did you capture that?

A: All of it had to be handheld, all of it had to be dusty, all of it had to be in the streets. I'm right in there amongst it all with the engines and the machines. You've got to smell the dirt and smell the shit, and the dust. I believe that things that fly through the air are all elements that are part and parcel of the visual side of the film. Even when I would create images in commercials, I would say, 'God that room's boring,' so we'd start using a little bit of smoke. Or, if I'm outside, I'll say, 'I want a bit of dust coming out of the propellers.' I really learned that from other directors, particularly Kurosawa in Seven Samurai and Throne of Blood. John Ford was a master of the universe in landscape and elements and dust and sunshine. And that's before the actors get there, right? The proscenium is so staggeringly powerful that the actor in there had better be able to compete. I'd never be able to say that to an actor, but that's what it is.

Q: Were the 11 cameras you used on Black Hawk the most you've ever used?

A: No, that was the most I'd done to that point. On Robin Hood, to get the beach scene at the end in nine days, we had to have up to 18 cameras. The beach is a mile long and the boats are pegged out between where the effects will begin. I've only got eight boats, but coming in digitally there will be 400 French ships. I've got 125 horsemen, but digitally there will be 400 horsemen. On the top of the cliff, I've only got 200 archers, but on the cliff top there will be 1,000 archers. But there is no cliff. It was sea, beach, dune, and farmland. That cliff was brilliantly put in on every shot by the visual effects company. I boarded that out and realized I needed 18 cameras. We had nine days to shoot this when we should have had, in my opinion, four weeks. But I said, give me the cameras, we'll be through in nine days, and we got through in nine days.

Q: So obviously you're a fan of CGI.

A: Oh yeah. Visual effects are a tool. The danger is when it becomes the film. That's when it gets boring.

Q: What about the flying arrow at the end of Robin Hood. How did that shot come about?

A: I thought, I've got to have the significant arrow shot because this is Robin Hood. You've got a good one at the beginning where Robin goes 'whoop' and lets fly, but I didn't want any target practice and all that bullshit. So I did the shot at the end, where he gets Mark Strong through his neck. That's all built digitally. You'll notice, Mark Strong goes 'HHHAAA,' the arrow has actually missed the jugular, just missed the windpipe. I wanted to keep him alive because of the sequel. If I want him alive, he's alive.

Q: For someone who made his first film at 40, you've done a lot of movies. What's pushed you?

A: It's just that it's the ethic I learned, I don't know where it comes from. Tony's exactly the same. Between Tony and I we've done 43, 44 movies. Just the films we've made, not the producing and the TV shows. And it's just who we are. There's just that engine. I get up every morning rubbing my hands together. Seriously. That's the way it is.

Q: And you don't do anything unless it appeals to you?

A: Never. Can't. I've got to go to work every day. I've got to enjoy it. But that said, if I was out of work, I think I'd paint. I'm painting just in case the day job wears out.