BY SCOTT FOUNDAS

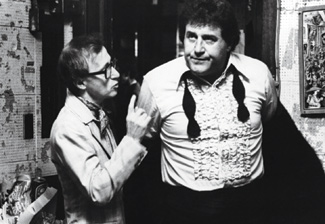

A GOOD FIT:Although their relationship started almost by accident,

A GOOD FIT:Although their relationship started almost by accident,

Woody Allen and Juliet Taylor have worked together for most of

their professional lives. (Credit: Brian Hamill/AMPAS)

If asked the question, "Who is Woody Allen's closest, most trusted, and longest-serving collaborator?" how many film buffs would correctly guess his casting director, Juliet Taylor? Yet theirs is a creative partnership that spans 38 films made over the last 35 years, from Love and Death in 1975 to the forthcoming Midnight in Paris, which was shot in France this summer. It's a collaboration made all the more intriguing by Allen's famously private working methods and his extraordinary track record with actors, which has yielded 16 Oscar-nominated performances to date, including six winners. If, as Robert Altman opined, "Casting is 90 percent of a motion picture," then the evidence suggests that Allen and Taylor are doing something very right.

It is also a meeting of minds that, like so many serendipitous ones, occurred purely by chance. Allen's third film as director, Bananas (1971), was cast by the legendary Marion Dougherty—the first casting director to receive front-credit billing on movies—for whom Taylor then worked as an assistant. Dougherty went on to cast Play It Again, Sam (1972), which Allen wrote and starred in for director Herbert Ross. But when Allen returned from the West Coast shoot of Sleeper (1973) and was starting to prepare Love and Death, Dougherty had taken a hiatus from casting to explore a career as a producer. So, he simply turned to Taylor instead.

"I was 25 years old, I was terrified," said Taylor—an industry vet whose illustrious résumé also includes multiple films by Louis Malle, Mike Nichols and Alan Parker.

"By the path of least resistance, I inherited her," added Allen in a separate interview, shortly before decamping to shoot Midnight in Paris. "That was very lucky for me, and I've just worked my whole life in film with her."

THREESOME: Allen wrote parts for Penélope Cruz and Javier Bardem in

THREESOME: Allen wrote parts for Penélope Cruz and Javier Bardem in

Vicky Cristina Barcelona, but doesn't often do that. Scarlett Johansson

completed the triangle. (Credit: Everett)

Even when interviewed individually, Allen and Taylor project a kind of symbiosis that offers a window into the inner workings of their relationship. At times, they suggest two halves of a single brain, telling the same stories in virtually the same words, or picking up a thought exactly where the other left off. At others, one senses from Taylor a maternal guidance, as well as an occasional need to lay down the law. It is, in Allen's own words, something "more dimensional" than the standard director/casting director relationship—a reciprocal give and take that begins as soon as Allen finishes a new script and continues well into the editing room.

So, how does it work exactly? "Usually, I get a call around the holidays, and he'll want to talk about what he's thinking of doing," says Taylor. "Sometimes it might be a script I'd read previously, or it's something new he'll want me to read. Then I'll tell him what I think and give him my advice."

"She actually talks about the script not from a casting point of view, but from just a generally creative point of view, a writing point of view, a directorial point of view," adds Allen. "Then of course we get to the casting."

At this early point in the process, a typical conversation between Taylor and Allen might concern various possible interpretations of a character. "Sometimes, we'll put casts together in our heads for a number of different age groups, or different acting styles, which helps Woody fashion [the script] to where he wants to get it," she says. "There's a lot of that kind of talking around the approach to it."

One case in point is the forthcoming Midnight in Paris, a romantic comedy set in the City of Lights starring Owen Wilson, Michael Sheen, Adrien Brody, and Marion Cotillard.

"Juliet always felt that the lead character was too young and unaccomplished, and it made him too much of a failure, too much of a loser," says Allen. "She encouraged me to make the character older, and to just have the plot point that the picture turns on be one of his little idiosyncracies and weaknesses, but that in general he would be a wealthy, successful non-loser. That was a big change in the character, and it required a change completely in the casting of the picture as well. Instead of having to get a cast that basically was under 27 years old, I could suddenly cast between 25 and 45, so a lot of excellent people suddenly became possible."

Only rarely, Allen notes, does he write characters with specific actors in mind, save for the ones played by himself, and those played by his longtime leading ladies Diane Keaton and Mia Farrow in his films of the 1970s and '80s.

"I wrote Penélope Cruz's part [in Vicky Cristina Barcelona] knowing I was writing it for her, and I also wrote for Javier Bardem," says Allen. "But this is a tricky thing, because very frequently you can't get the person. You write something for someone, and then he's on a film that takes him to Africa for 15 weeks and you have no chance of getting him." To wit, when Allen originally wrote the script for his 2009 comedy Whatever Works in the 1970s, he conceived it as a starring vehicle for Zero Mostel. When Mostel died, it took Allen more than 30 years to find a suitable replacement in the form of Seinfeld creator Larry David.

Once he sends Taylor a finished script, she then begins breaking it down in terms of the individual roles. "She'll usually make a list of a number of actors or actresses for each part," Allen says. "I'll look at her suggestions, and I may say right off the bat, 'No, I don't really like the idea of this person for this part,' and that may kill that idea for life. Or, she may disagree with me and in a very tactful way bring it up again two weeks later when we haven't found anybody yet. And I'll say again, 'No, I could never stand that person.' But, you know, she may bring it up a month later when we're still looking, and then that person will start to look like the best person to me."

FUNNY FACES: Nick Apollo Forte in Broadway Danny Rose

FUNNY FACES: Nick Apollo Forte in Broadway Danny Rose

was one of Taylor's big finds.

Sydney Pollack in Husbands and Wives.

Jeff Daniels and Mia Farrow in The Purple Rose of Cairo. (Credits: Everett)

Sometimes, Allen and Taylor drive themselves crazy, only to find that the perfect solution is staring them in the face all along. When the time came to cast the Cristina role in Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008), both Allen and Taylor resisted the temptation to cast Scarlett Johansson, given that she had just starred back-to-back for Allen in Match Point (2005) and Scoop (2006). "Even though he was crazy about her and I think really wanted to use her, we sort of thought better of it," says Taylor. "We felt we should do something different, that it shouldn't be so fast on the heels of the other movies. So we really, really looked around to see if we could cast someone else. And at a certain point, we felt like we were just going around in circles, because we were looking at people who were so much less interesting, who just couldn't bring as much to it."

Casting with Allen is certainly not without its quirks—chiefly, his innate reluctance to meet and audition actors in the first place, an obstacle Taylor has found herself negotiating since the early days. "When I first knew him, when I was an assistant on Bananas, his line producer Fred Gallo used to speak to all the actors," Taylor recalls with a chuckle. "Woody just sort of sat in a chair and watched."

"Now, I talk to them," Allen responds, "but very sparingly, because the whole thing for me is awkward." Those encounter sessions—not auditions in the classical sense—typically last no more than a minute, a fact that catches many of them off guard. "With Mike [Nichols]," Taylor says by way of comparison, "he will sit and chat, spend a lot of time, amuse them, and will always give them good tips. Woody's feeling is that his own way is great; he's not bothering anybody and he's not taking up too much of their time. And I say, 'But they want to have more of their time taken up!' I think for actors it's probably a little frustrating, but they all sort of know about it now. People are amused by it. You still have to warn them so their feelings aren't hurt, but pretty much everybody thinks it's a funny, quirky thing."

"People are always asking, 'How do you guys cast if someone comes in and you speak to them for 60 seconds—they don't sit down, they don't take their coat off?'" Allen says of his unconventional process. "Well, we really cast beforehand. We cast from tapes and from having seen films with the people, and we think, 'This girl is great. She'll be wonderful.' And we only have her come in as a kind of reality check, to make sure that she hasn't doubled her weight or gotten fatal face work or she's really a nightmare the minute she walks in the room. After two or three questions like, 'What are you doing in town?' or 'Are you from New York?'—meaningless questions—I hear their voice, and if they answer politely, and they don't grab me by the throat and pin me to the wall, then I say, 'Thanks for coming.' Once we think an actor is good and we've seen them deliver for other people and we bring them in, it's almost never that they blow it in any way."

Almost, but not quite. It was, Taylor admits, Allen's reluctance to meet actors—and to have actors read when he did meet them—that led to several high-profile cases of recasting on his films after production had already begun. For instance, fresh off of his star-making roles in Night Shift (1982) and Mr. Mom (1983), Michael Keaton was chosen by Allen for the role of the 1930s movie character who literally walks off the screen and into the life of Mia Farrow's small-town waitress in The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), only to be replaced during the shooting by Jeff Daniels.

"He thought Michael Keaton was great," recalls Taylor. "He just thought he was too contemporary. He didn't meet him first. If he had met him, he would have known that."

On Husbands and Wives (1992), British actress Emily Lloyd (who had made an international splash in 1987's Wish You Were Here) was cast in the role of the student mistress of Allen's 50-something English professor—a role ultimately played by American Juliette Lewis.

"Even though Emily came in to meet him, she did not read as I recall," says Taylor. "If she had, this problem could have been solved. Emily's charm was so keyed in to her cockney-ness. You have to be really aware that if you take someone's essential quality—that humor—away from them, are they going to be what they were? Not all English-speaking actors can act in a different accent, or be as much fun in a different accent."

"It's usually my mistake," says Allen in hindsight. "I've seen the person do other things and they look perfectly fine to me and I cast them, and then I find that for whatever reason I can't get it out of them. It's not to say that they don't have it in them, because I've seen other directors get it out of them before, but I can't do it. I try doing it for them. I try every little gentle trick that I can in the world, and sometimes that's effective; I manipulate them and they do it properly and it's great. But there are times when it's beyond me. I sit in dailies night after night for three, four, five nights, and other people seeing dailies with me will say, 'It's just not happening. I don't buy this guy as that person for a second.'"

In this respect, Taylor says, Allen has made marked progress. "I try really hard to say, 'I think this person is a really talented actor, but I don't know how great they're going to be at this particular role, if it's in their range. We've got to really read them in depth,' which is something he wouldn't do before but he does do now."

Still, it wasn't until the first day of shooting on Whatever Works (2009) that Allen thought to inform actor Ed Begley Jr. that he needed to perform his role in a Southern accent. "The first shot we shot in the movie was with him, and he had no idea," Allen recalled in a 2009 interview. "I said, 'You know you're going to have to play this with a Southern accent. You do do a Southern accent, right?' Begley said, 'Well, I think I can.' I said, 'Okay, because I assumed you knew that when you read it.' But he didn't, and he just simply did it. So much for the meticulous preparation."

Broadly speaking, Allen casts from gut instincts and first impressions. "There's an impact or a feeling he has in mind, that he wants to get across when that person is onscreen," Taylor observes. "Particularly back when we were doing kind of crazy projects like Stardust Memories (1980) and Zelig (1983), with lots of odd characters in them, someone would come in and Woody would really have to bite his lip not to laugh, because the person would be so funny to him and exactly what he was thinking. So I think he casts people that he knows are going to be what he was thinking of, if that doesn't sound too simplistic."

"I always look for people that are not going to come across as actors acting," says Allen. "Now, I've worked with Gene Hackman [Another Woman (1988)] and Leonardo DiCaprio [Celebrity (1998)]—these people are actors who act, but they're so enormously gifted that you can't tell they're acting. They sound like real human beings in that dilemma or that situation."

To that end, Allen has often cast nonprofessional actors in his films, from Marshall McLuhan's self-effacing cameo in Annie Hall (1977) to the parade of real-life talking heads (Saul Bellow, Susan Sontag, et al.) in Zelig and the cavalcade of Borscht Belt comics telling war stories at the Carnegie Deli in Broadway Danny Rose (1984).

After Zero Mostel died, it took Allen more than 30 years to cast

After Zero Mostel died, it took Allen more than 30 years to cast

Larry David in Whatever Works. (Credit: Roger Arpajou)

THE RIGHT BANK: Allen, with Marion Cotillard and Owen Wilson,

cast Midnight in Paris older at Taylor's suggestion. (Credit: Everett)

"Sometimes, when Juliet and I are casting and we can't come up with anybody for a part, we start to think, 'Well, maybe we should think of a real person. Maybe we should think of a director, like Sydney Pollack or Mark Rydell,' because many times directors can act," Allen says. "Or sometimes we think in terms of rock stars"—like Madonna, who appears briefly as a tightrope artist in Shadows and Fog (1992). "Juliet once even brought in some guy from the checkout counter at the supermarket who she thought was right for something, and I think we used him."

In the case of Pollack, who is featured in a prominent supporting role in Husbands and Wives, Taylor recalls insisting that Allen audition the director, who, despite beginning his career in front of the camera, had been absent from the screen for decades (save for a memorable role in his own film Tootsie). "This is what was so painful for Woody," says Taylor with a smile. "He said, 'How can I ask Sydney Pollack to read? He's Sydney Pollack!' I said, 'Well, you have to be a little uncomfortable with it, because you've got to read him. You've got to know. It's a huge part.' And Sydney was so great, too. He read through the entire script with us."

Particularly on Allen's broadly comic films of the 1970s and '80s, Taylor would cast her net as wide as she could in order to fill out the Felliniesque panoramas of eccentric supporting and bit players. "I used to have a card with just my office telephone number on it, and if I saw someone totally goofy, I'd say, 'I'm a casting director, here's my card,' she says. "I had a Woody Allen picture file."

For Broadway Danny Rose, the Oscar-nominated farce about a New York talent agent representing a cavalcade of has-been ventriloquists, balloon twisters and stand-up comics, Taylor even put out a call for actual novelty acts from the then-dying upstate Borsht Belt resort circuit. "For me, it was the most fun of all of his movies to work on," she says. "We had a day when we saw nothing but novelty acts, and I talked to agents who were disappearing at the time who did the Catskills. They were in New Jersey and Long Island—they weren't in New York City anymore—and they were still booking these clubs with women who played the glasses and crazy stuff."

It was also on that picture that Allen and Taylor discovered real-life lounge singer Nick Apollo Forte, who made a splash as the film's over-the-hill crooner Lou Canova, and then promptly returned to his singing career, never to appear in another movie.

"We looked at everybody for that part, including a lot of real professional singers—Robert Goulet was one," Allen recalls. "We even shot film on these people to look at them doing it. Then Juliet was browsing in the Colony Record Shop on 42nd Street and saw an album cover with Nick's picture on it. He was a guy from Connecticut who worked these little clubs, and he did a nice audition. Then I had a cluster of finalists, a number of whom were very famous—Jerry Vale was in there. So I showed the audition tapes to Diane Keaton, who is one of my north stars for these things, and she said, 'This guy is the best,' and I had to agree with her."

"The funny thing about Nick Apollo Forte was that it was as if he knew this was going to happen to him," says Taylor. "He was like, 'This is my big break and I knew it was going to come.' He had so much confidence, which is what enabled him to do the part."

Once an actor is set for a role, it falls on Taylor to negotiate the deal, per Allen's longstanding house terms. "Many years ago we set up a system," explains Taylor. "We made a hard-line specific salary that the stars get, which is only scale plus a little, and everyone else gets scale. Everyone pretty much knows that. But there are the occasional people who for some reason don't—some of the agents. So you always have to go over things that are really unthinkable to agents, such as, we do not give an extra airfare or per diem. And there are zero perks, none. No nannies. No assistants. Nothing. That always seems to come as a shock. They sort of don't believe it."

While the start of shooting should mean the end of Taylor's heavy lifting, there was a time when it was the part of working with Allen she dreaded most. "He's the nicest guy I've ever worked with, [but] he can be a difficult director in the following ways," she says. "He has peculiarities, such as he doesn't like to shoot in the sun, and back when he had enough money that he could goof around a little bit, he would say, 'Oh, it's going to be sunny tomorrow, I don't want to shoot that.' Then I would have to switch everything around and argue with the agents and redo deals and sometimes even recast. It was a nightmare. The job never ended until the movie wrapped."

In that regard, Allen's European-shot and financed films of the last decade have made Taylor's life a little easier. "First of all, he can't really goof around like that anymore, and second, it's going to be on the European casting director's desk if it does happen. Now, if he's unhappy with someone when he's there, he really does have to kind of work it out."

Contrary to conventional wisdom, Allen points out, he is frequently turned down by actors he asks to appear in his movies. "It's not that every single actor I want thinks this is a great privilege," he says. "There are some that delight in the idea and others that turn me down just as quickly. They don't like the script or they find, when they think about it, they don't really like the money and don't feel the part is going to elevate their career sufficiently to make up for the lack of money. Or whatever. Then we move on to the next person."

Still, if Midnight in Paris and the recently released You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (featuring Josh Brolin, Anthony Hopkins, and Naomi Watts) are any indication, the queue to work with Allen remains very long indeed.

"I think one of the big attractions is that many, many actors come off one of Woody's movies looking the best they ever have," suggests Taylor. "Physically, he's great dressing women, styling women, and in many cases gives them the most complete and accessible characters they've had. When Judy Davis did Husbands and Wives, I don't think anyone had ever seen her play an American before. I don't think anyone had seen her play comedy before. Those parts are really so valuable to an actor. Also, I think some people just want to know that before they die they've done a Woody Allen movie—there's a little bit of that."