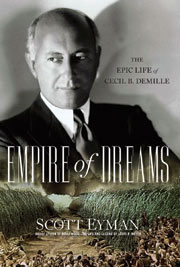

(Simon & Schuster, 592 pages, $35.00)

By Scott Eyman

Scott Eyman opens this marvelous biography with Cecil B. DeMille's best-known appearance on film, in Sunset Boulevard, playing himself under the direction of Billy Wilder. This depiction of DeMille as the discoverer/director of Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) is benign and respectful. Despite the fact that he is clearly playing a role, this is perhaps the image of DeMille that has remained in the public's mind more strongly than any of the director's own movies, or of any more realistic appraisals of the man himself.

Scott Eyman opens this marvelous biography with Cecil B. DeMille's best-known appearance on film, in Sunset Boulevard, playing himself under the direction of Billy Wilder. This depiction of DeMille as the discoverer/director of Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) is benign and respectful. Despite the fact that he is clearly playing a role, this is perhaps the image of DeMille that has remained in the public's mind more strongly than any of the director's own movies, or of any more realistic appraisals of the man himself.

Eyman reminds us in this beautifully written, deeply researched and appropriately "epic" biography how DeMille's rise in early Hollywood not only paralleled the industry's ascent to global prominence, but was inextricably intertwined with it. DeMille ended his life pondering a future project with science fiction themes, but he arrived in cinema a lifetime earlier, as it emerged from the lavish excesses of late 19th-century American theater. He started as a stage actor under the tutelage of producer David Belasco, whose combination of extreme spectacle, sex, violence and shock value offered a clear template for DeMille's own cinematic vision after he himself had become, like Belasco, a full-fledged impresario, showman, and artist.

If DeMille's reputation has declined, says Eyman, it's because his signal achievements—The King of Kings (1927) and The Ten Commandments (1923)—came before sound (though he was the only major silent director to survive the transition and thrive), and have thus slipped beyond our modern gaze like the sets from The Ten Commandments, still interred beneath the sands of Nipomo Dunes near San Luis Obispo. Eyman, however, armed with unprecedented access to the DeMille family archives and a deep understanding of early Hollywood, restores DeMille to his rightful prominence in the rise of the industry and as a pioneering filmmaker. In real life, DeMille did in fact discover Swanson and also Claudette Colbert. He was a founding partner of Paramount Pictures, and the director who most swiftly absorbed the basic cinematic grammar laid down by Thomas Ince and D.W. Griffith.

But one event in later life—his divisive attempt to unseat the supposedly too left-wing Joseph Mankiewicz (a registered Republican) as president of the Screen Directors Guild on October 22, 1950, and his call for a Guild loyalty oath—has damaged DeMille's reputation ever since. Eyman does not absolve DeMille of nefarious procedural tactics or for being an eager list-maker and McCarthyite. But, as he points out, DeMille was also for many years a Guild member in good standing and in good faith, and graciously accepted his own defeat—and that, he says, should count for something.

Review written by John Patterson.