BY ROBERT ABELE

AWESOME: Zack Snyder remembers the cool

AWESOME: Zack Snyder remembers the cool

thing

about Excalibur when he first saw it was that

it

wasn't a kid's movie. (Credit: Warner Bros/Everett)

To be a male teenage movie nut in 1981 was to revel in the PG razzle-dazzle of superheroes (

Superman II), ancient monsters (

Clash of the Titans), and a Fedora-sporting archaeologist (

Raiders of the Lost Ark). But for Zack Snyder

the be-all end-all cinema experience of that year was John Boorman's R-rated

Excalibur, a visually dazzling collage of mythmaking, mysticism, bygone heroism and sex-and-blood thrills. "The cool thing about this movie is that it's not a kid's movie," says Snyder as we settle down to watch the Arthurian epic at his offices on the Warner Bros. lot.

The Dungeons and Dragons-obsessed boy, who would grow up to bring new levels of sophisticated graphic mobility to the sword-and-sandal epic (300) and the caped-crusader saga (Watchmen), recalls the feeling of seeing the oft-told tale get a decidedly adult treatment. "Everyone thinks, 'Oh, it's a movie about King Arthur, it's gotta be accessible.' But no. This went further than I thought it would." What has stayed with Snyder over the years and perhaps influenced him the most as a director is the film's then-eyebrow-raising bloodletting. "I guess when I come to a part in my movies where there's an opportunity for it to be gory, I say, 'Okay, let's film that.' It's not my aesthetic to use trickery to get around it. In Watchmen, I always felt the truth of being a superhero is that people frickin' get killed. And that's what Excalibur is. It's violent because that's what it was like."

Boorman filmed a lot of Excalibur in the oak forests around his home in Ireland to capture a sense of old, undisturbed, fragrantly green countryside, which Snyder admires. "That's what's cool about Boorman, to be so inspired by the land where you live to make a movie like this," he says. "I shot a commercial there once, and the location scout was an old-school guy who'd worked on movies, and I kept saying, 'Was that in Excalibur?' And he'd say, 'Yeah, yeah.' I was so excited." As Trevor Jones' Wagnerian score takes us from the Orion logo to an explanatory crawl ("The Land Was Divided And Without A King") and finally a shimmering title card, Snyder says, "I do know that this movie is one of the last great mono mixes. It all came out of the screen. They just don't do that anymore. You hear, 'Mono's not as good as stereo,' but there's an art to everything, and you've got to believe the mixers here had to be geniuses, because they only had one track and it's beautiful."

"It's like Boorman took an iconic moment and made you understand the why

"It's like Boorman took an iconic moment and made you understand the why

of it," says Snyder. (Photo Credit: Screenpulls Courtesy Orion Pictures Corp.)

Boorman lays down a visual gauntlet right away with a jagged tree ridge lined with armored horsemen, backlit with a blood-red glow. A literally fiery battle commences—the forces of Uther Pendragon against the Duke of Cornwall—and it's all clang and sweat and knights meeting the bad ends of lances and axes. "He's not interested in the bright and the happy version of knights," notes Snyder, who shares with Boorman a love of the mono-saturated, bloody grandiosity of fantasy/sci-fi artist Frank Frazetta. "I was such a freak for fantasy horror things, that whole Frazetta palette, and this movie has that."

Out of the crimson mist steps Merlin, played by Nicol Williamson, who is beseeched by Gabriel Byrne's Uther to give him a promised sword so he can be king. Man's thirst for power is made immediately apparent here by Byrne, in his first screen role. "Boorman has an amazing sense of casting," says Snyder. "These are the premier English actors."

A dissolve takes us from the burning imagery of war to a calm green lakeside, as Merlin stares toward the water. Then, in slow motion, the tip of a sword emerges from the surface: Excalibur rising from below in the hand of the Lady of the Lake, with a green gleam reflecting off the weapon.

"It's an awesome image," says Snyder. "The thing about Boorman is he's one of those rare guys who combines drama and being a visualist. The drama of the movie is clearly the most important thing to him, but the way he sees it is incredibly painterly. This is like the stylized other England you want the Middle Ages to be. It's as if it takes place in no particular time in history. Like it's another planet in some ways."

Boorman cements the "one land, one king" idea embodied by the film in a scene by a stream between the warring Uther and Duke of Cornwall. Merlin announces Excalibur's presence and Snyder delights in Williamson's delivery. "Forged when the world was young, and bird and beast and flower were one with man, and death was but a dream!"

Snyder points out that Williamson's baroque, singsong vocal performance is decidedly quirky, but says it's essential to grasping Merlin as a figure of charm, cunning and irony. "Anyone would say it's insane, but it's also perfect."

Suddenly it seems as if an emerald glow is everywhere. "The sword is an organic life force," says Snyder. He then points to the image on his flat screen. "There's a green kick to everything, even in the water." The truce is broken when Uther's lust for Cornwall's wife, Igrayne (Boorman's daughter Katrine), becomes all-consuming. Uther lays siege to Cornwall's seaside castle in a sequence composed of backlot filming at Ireland's Ardmore Studios. When the scene shifts to night, Boorman uses a wide shot employing pre-digital effects work. "It's not a real castle," says Snyder, pointing to a shot of the looming fortress with Merlin a tiny figure at the bottom preparing to cast a spell to

help Uther. "That's a glass matte painting."

Boorman used pre-digital effects and a glass matte painting to create the fortress.

Boorman used pre-digital effects and a glass matte painting to create the fortress.

Nicol Williamson as Merlin the magician.

Boorman shot in the woods of his native Ireland and gave the whole film an otherworldly

green tinge. (Photo Credits: Screenpull courtesy Orion Pictures)

Next comes a key piece of operatic storytelling: while the Duke is in the village with his men, Uther—transposed by Merlin into the Duke's form—enters the castle and seduces the unwitting Igrayne. Boorman then crosscuts between the Duke accidentally getting impaled, and the violent sex between Uther and Igrayne.

"This sequence had such a huge influence on me," Snyder says about the crosscutting between bloody death and raw sexuality. "It's so well-constructed, putting those two things together, so when Uther climaxes, the Duke dies." After Uther plunges Excalibur into a large stone with his dying breath, ending the first act, Snyder is intrigued by how Boorman starts up again with a nifty double reveal: as a knight rides up, the camera pans to show the lodged sword in the foreground. Then the knight rides away, and the shot continues panning from the sword's POV, revealing the village that's sprouted up around the mystical weapon. "It's a cool transition because in some ways, the movie is

more about the journey the sword takes," Snyder notes. "Of course, they had to shoot this at a different time of year because in the earlier scene there weren't any leaves on the trees."

As knights gather to fight for the right to try (and fail) to draw the sword from the stone, a young knight's apprentice, Arthur (Nigel Terry), ordered to find his master's sword for an upcoming joust, yanks it out with no trouble, sealing his fate as future king. In a clever two-shot, Arthur learns his true origins from his adopted father, while a far-off

Merlin slowly comes into focus walking toward the pair. "That kind of coordination is tricky, all this drama while someone walks in. But it's about destiny, which plays a big part in this movie," says Snyder, admiring the intricately choreographed compositions. "It's a different way of seeing. Directors are lazier about that kind of thing nowadays."

Fortified with his sense of destiny, Arthur rallies to help friendly knight Leondegrance (Patrick Stewart), whose castle is under siege by Uryens, a fellow knight. "Having worked with armor recently for Sucker Punch, I can say it's super unforgiving," says Snyder, wincing at what the actors and extras are going through filming another clanging, vicious mêlée. "Our stuntmen were falling and the armor cut their neck. It was a nightmare."

Snyder marvels at how Boorman is able to mix moods so effortlessly. After Arthur's success in battle earns him the the hand of Leondegrance's daughter Guinevere, and all is festive, Merlin unveils the prophecy that "a dear friend will betray you." But Arthur isn't paying attention, and Boorman uses Merlin's exasperation to play the moment for a laugh.

"It's the idea that men are powerless," says Snyder. "All the things that make us men—love, hate—that's

our downfall, the thing that destroys us." The movie segues, as if on cue, to Arthur meeting Lancelot (Nicholas Clay), who's looking for a noble knight better than himself to swear fealty to. His polished chrome armor is the shiniest in the film so far, signifying a chivalric ideal soon to take hold. "It's almost sci-fi looking," says Snyder, somewhat envious of the armor. "It instantly turns Lancelot into some other thing. But I always wondered how they got away with not seeing the camera in it."

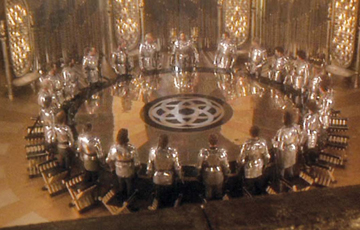

Snyder perks up over a dynamic Boorman shot in the next sequence where Arthur breaks Excalibur against Lancelot in a fit of rage. "I like it when he puts the camera right at the water level," he says, as the Lady of the Lake then holds the restored sword above the water's surface. "He did it with Uryens' moment with Arthur, too." Lancelot and Arthur become fast friends, and in a moment of postwar revelry atop a mountain, Merlin inserts himself amongst the celebrating knights, forcing the men to step back into, naturally, a circle. The camera pulls back and up to show the geometry of the moment. Observes Snyder, "It's like Boorman took an iconic moment, the formation of the Round Table, and made you understand the why of it."

The Lady of the Lake rising with Excalibur intact is impressively shot with the camera

The Lady of the Lake rising with Excalibur intact is impressively shot with the camera

at water level.

Snyder pauses to make a point, explaining how Boorman approaches myth in the film as opposed to what he did with it in 300. "This is a myth that Boorman's making real to us," says Snyder. "We took a real event and made it into a myth. If you were a Spartan sitting around a campfire, and someone was telling you the story of the Battle of Thermopylae, how would it appear to you? How did people make pictures in their mind before movies? That was the style part of 300."

Style is again on Snyder's mind during a later sequence involving the search for the Holy Grail. Perceval the knight is captured and strung up on a tree alongside dead, rotting knights. Boorman cuts between a dead knight swinging, his spurs slowly cutting Perceval's rope, and a luminous, dream world in which Perceval finds the Grail. "It's the land between life and death where the Grail resides," says Snyder. "There are a lot of cool parallels in this film, and the lighting helps establish the two realities. It's awesome how surreal all this stuff is."

Perceval manages to retrieve the Holy Grail and Arthur is rejuvenated by its purifying powers. The king rides through England as it literally flowers before our eyes. Boorman intensifies the transition with a shot of blooming apple blossoms filling the air like snowflakes.

"It's that land-and-the-king-are-one concept again," says Snyder."It's so beautiful." Boorman also reprises the use of Carl Orff's "O Fortuna," a swatch of blood-stirring Germanic music that was novel and thrilling at the time, but in Snyder's estimation has been overused in movies since. "It's almost like parody now," he says wistfully.

As Snyder points out, Excalibur wasn't a big-budget film, but it did have ingenuity. So Arthur's wicked half-wizard half-sister Morgana (Helen Mirren) and her son Mordred (Robert Addie) are forced by Merlin to create a mystical fog to conceal from them the fact that Arthur doesn't have as many men as they do. What served the story also served the filmmaker because Boorman didn't have many extras. "It's a clever device, because this was a low-budget movie," says Snyder. "The fog aided the filmmaker, too!" In the final battle against Mordred, a hairy, slightly mad-looking Lancelot returns from willful exile to help his old friend. Fatally wounded, he asks Arthur's forgiveness, to which the king says, emotionally, "You are what is best in men." Snyder is moved. "I cried like a child when I first saw that scene, and it still makes me slightly choked up," he admits, then cites how its invocation of honor among men influenced his approach to the death of Dilios in 300. "It's the most amazing declaration. This rang in me when we shot Dilios telling Leonidas, 'It's an honor to die at your side,' and Leonidas says,

'It was an honor to have lived at yours.'" Snyder excitedly anticipates the end by reciting one of his favorite lines of dialogue: Mordred's eerie beckoning, "Come, father, let us embrace at last." What follows is a majestically unreal tableau: an impossibly massive and artificially red, hazy sun centered behind Mordred as he impales Arthur, who in turn gores Mordred with Excalibur. "Now that is very theatrical," says Snyder, who recreated this violent image for a climactic showdown in 300. "Boorman did this on a big stage, instead of on location. That is one crazy fake sun. It's like a Kurosawa movie."

As the film draws to a close with a majestic ocean vista of three ladies in white escorting Arthur's body to Avalon, Snyder muses on why genre films like Excalibur mean so much more to their fans than other types of movies. "People who like these kinds of movies, they're searching for something," he says. "It's like a lifestyle choice. You learn the dialogue. You really know the movie. I mean, after you see this, you go buy a sword."

And yes, Snyder did. "It wasn't the exact same one," he says, laughing, "but it was the closest I could find."