BY DAVID GEFFNER

"I enjoy making sure directors have every chance to realize their visions

"I enjoy making sure directors have every chance to realize their visions

exactly as they intended. The the bigger the canvas they have to work

with,

the more challenging and fun my job becomes." - Josh McLaglenWho is "Zulu" and why are directors heaping praise upon him like Purple Hearts at a veterans' convention? Shawn Levy, who has done four films with him, says he is one of the best ADs in the world, period. "On Night at the Museum 2, he trained all our military henchmen. We're talking everything from Russian Streltsy fi ghters to Napoleonic guards to Pharaoh's foot soldiers, which completely freed me up to focus on the comedic bits. 'Set general' is a clichéd term, but in Zulu's case it fits."

"We've done four movies together," says Robert Zemeckis, "and the energy Zulu brings to my sets, all the nicknames and jargon [Zuluisms], and the sheer love of filmmaking is, I'd like to think, a throwback to the John Ford era. I mean, c'mon, the guy's grandfather worked on Gunga Din." So what does 1st AD Josh McLaglen (he adopted the nickname Zulu after working with South African tribesmen on The Ghost and the Darkness in 1996) have to say about all this acclaim from his fellow filmmakers?

"I just really enjoy making sure directors have exactly as they intended," says McLaglen. "And the bigger the canvas they have to work with, the more challenging and fun my job becomes." A "fixer" who pulls rabbits out of a hat was the description DGA President Taylor Hackford heard before hiring McLaglen for Bound by Honor in 1993, the first film to shoot inside San Quentin. "After just two days our 'set' was anarchy because we had hundreds of convicts for extras,"

Hackford recalls. "It was an impossible situation, like trying to control 300 bad boys at the back of the schoolroom."

Line producer Stratton Leopold told Hackford he knew an AD who could handle it. "So Josh comes up from Hollywood," continues Hackford, "and on his fi rst day he starts asking the inmates their names—Lalo, Spider, Chuy—and I'm thinking: 'What is he doing? There are 300 of these guys.'"

The first day McLaglen memorized 45 names, the next day 60, and so on until he knew all 300 names. "He would huddle off in the corner telling them, 'This director thinks he's a big shot, and you need to show him the real deal,"' Hackford laughs. "Now mind you, these are people who have been disrespected their entire lives, and within a week they were all Josh's guys. He literally saved the film."

"My mind works and thinks in big problemsolving ways," McLaglen reflects. "And," he laughs, "like anything else you get typecast after doing a few of these pictures. As my wife used to say, 'Honey, they never call you on the easy

ones.'"

Bigger has never been a problem for McLaglen, who among his many exploits can count organizing a lunar eclipse inside a hockey arena for Hackford on Dolores Claiborne and dangling a food-baited lure in front of a rampaging lion for Stephen Hopkins on The Ghost and the Darkness.

GETTING IT RIGHT: McLaglen on a prehistoric set on Shawnn

GETTING IT RIGHT: McLaglen on a prehistoric set on Shawnn

Levy's Night at the Museum. (Credit: 20th Century Fox) Working on Cast Away in the Fiji Islands. (Credit: Francois Duhamel)

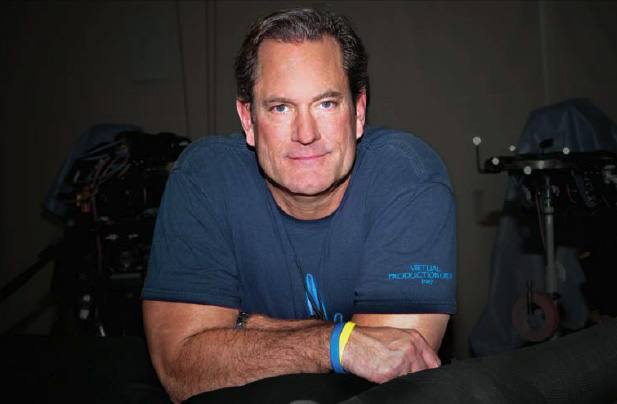

Working on Cast Away in the Fiji Islands. (Credit: Francois Duhamel) McLaglen with DGA President Taylor Hackford at a performance

McLaglen with DGA President Taylor Hackford at a performance

capture workshop. (Credit: Brian Davis)But that was just a preamble to working with James Cameron on Titanic and, more recently, helping to pioneer real-time performance capture (along with 2nd AD Maria Battle Campbell) for Cameron on Avatar. McLaglen says his first exposure to performance capture came six years after the overwhelming physical logistics he experienced on Titanic. "It was a time when I was looking for new challenges as an AD," which he found with Zemeckis on The Polar Express, the first all-performance capture live-action feature.

"Bob is a director who likes to work quickly, so performance capture was a perfect match for his workflow," McLaglen says of his experience with Zemeckis on The Polar Express. "We never had to cut or reset lights or camera, and Bob could run through Tom Hanks' four different characters like a stage play. My part was basically to help move everything along, given how quickly Bob wanted each setup on the mocap stage swapped out." Zemeckis recalls, "We determined in our production meetings that it should take no more than 15 minutes to turn around the set, so the first day I walk on the show, Josh has this huge countdown clock on the wall. When I said, 'Okay, time to move on,' Josh would hit a button, zeroing out the clock and starting another 15-minute countdown. He considered the day a failure if we didn't get every single shot I had

planned."

McLaglen credits everything he learned about performance capture to the work he did with Zemeckis on The Polar Express, and then later, Beowulf. "Those early iterations of the format were all about getting the actor's performances acquired as data and then sending it out to our keyframe render animation supervisors to have them build the environments and characters. The performance capture stage where we shot was just a big 36-foot by 60-foot rectangle, with cameras rigged to the ceiling to electronically capture the actor's movements; it's a blank slate of a space. I had to help grid out the volume to ensure the actor's movements were in correct scale and proportion."

On Avatar, McLaglen says the workfl ow breakthrough was a real-time capture paradigm, where the performers were rendered in their virtual environment simultaneously with the data being acquired. "So when Zoe Saldana walked into the volume, we could see her as Neytiri on the planet Pandora," he marvels. "The essence of capture from the AD's perspective," McLaglen says, "is ensuring all the technology works to the expectations of the director. Real-time motion capture is driven by a software engine called MotionBuilder, and because we were developing the whole system as we made Avatar, there would be many days we'd have an SC [small system crash] or a TF [total failure], so the technology was often controlling our schedule, not me." Learning the communication protocols was also a challenge. "As the 1st AD you have to initiate all of the system commands and initiate the sequence," he says. "Then you have to make sure the sequence is cut and saved before starting all over again."

A typical Avatar day would have Cameron capturing ten takes on any given scene before doing a "director's layout," similar to the three or four preferred takes a director would choose to print at the lab. "Once Jim had pulled his selects, I would make sure they were stitched together to form a sequence before the data was cleaned up and prepared for the virtual camera," McLaglen explains. "Once the data was all verified, I would bring Jim back in to do all his coverage with a virtual camera."

While McLaglen says performance capture is great for directors who want to incorporate surreal or otherworldly elements, he doubts it will ever replace traditional storytelling or become commonplace until the process is time and cost-efficient. "What's really important," McLaglen insists, "is for the AD team to learn these new technologies on the job and not in some virtual think tank.

"The motion picture industry is 'adaptive medicine,'" he continues, "and you can't learn how a movie set works until you are on one." That's why McLaglen and Battle Campbell have been promoting performance capture technology through DGA workshops, inviting as many production professionals as their capture volume can hold to walk them through the process. "Unlike the physical challenges you find on the big logistics fi lms," he says, "[for the AD] running a performance capture set is a mental challenge because there are just so many technological procedures to track and verify throughout the day. Performance capture is all about making sure the technology works to the specifi cations of the director."

As one of the few 1st ADs adept at the new technology, McLaglen's services are obviously in demand. Levy says he would not have attempted to make his latest film, Real Steel, where 2,000-pound robots duke it out in the boxing ring, without him. "Josh is really the person leading the charge for performance capture from the production side," says Levy. "Every day on Real Steel begins with me and Zulu talking for 15 minutes about how we're going to

make each shot and how to make our day."

Ask McLaglen how he's managed to keep some of the most ambitious fi lmmakers in the industry happy (he's also worked with David Fincher, Jan de Bont, and John Woo), and he says he's basically just a "big logistics guy, who's very good at moving people."

Take for instance the mother of all logistical films, Titanic. Talking about his experience, McLaglen sounds like an expert boatswain offering a tour of the ill-fated liner, all the way down to the historically correct number of rivets on the ship's plating and what degree of tilt was needed to sink the vessel. "James Cameron's attention to detail is so comprehensive that he had us all study the main accounts of the boat's sinking and test each other with questions like, 'Where was lifeboat 7 at 12:10 a.m.?'

"Every day began and finished with safety," he adds. "If an actor was interacting with a davit [the rope that lowered lifeboats], I had to make sure he was trained marine personnel or a stunt player. When 200 background artists jumped ship into the water, I had to ensure there were 20 lifeguards on watch, one for each 10 background players, because we could not put people in harm's way."

Recalling the shooting of a movie he made 13 years ago as if the Titanic crew had just broken for lunch, McLaglen says Cameron would never give him an order he hadn't first done himself. In one unnerving example, the director donned underwater gear—compressed air tanks and a handheld camera with a HyrdoFlex housing—to capture a scene of a father saving his son moments before hundreds of pounds of water surged through their cabin.

SETTING THE STAGE: (top) McLaglen working with actors on performance

SETTING THE STAGE: (top) McLaglen working with actors on performance

capture for Avatar. McLaglen credits his work with Robert Zemeckis on

The Polar Express and then Beowulf below) for everything he's

learned about performance capture. (Credits: Mark Fellman)"I was Jim's safety in case he was injured or overwhelmed by the rushing water, and my safety was one of the stuntmen," McLaglen remembers. "We had three minutes of spare air in our tanks, so when the door of the cabin blew, the stuntman grabbed the boy and within seconds we were all washed down the hallway in this torrent of water. Somehow I ended up on top of Jim riding him out like a surfboard. I will never forget the look on my director's face as I was staring down at him through his mask. He was like 'what are you doing? Get off of me.'"

Sometimes McLaglen's adventures making movies rival the action on the screen. For Zemeckis' grueling eco-adventure Cast Away, McLaglen spent six weeks on the Fijian island of Monuriki. "Cinematographer Don Burgess and I, along with a handful of other hearty souls," McLaglen grins, "became the Zulu Team"—a dogged band of crewmembers who took pride in being the first ones in, and the last ones out of the remote South Pacific location.

Living in refurbished liners moored off the island, the water warriors would board longboats in the pre-dawn darkness and motor their way toward shore. When a coral reef would halt their progress, they jumped overboard with waterproof duffels and swam the remaining 50 yards to the beach.

McLaglen's AD duties have even called on him to handle a man-eating animal while shooting The Ghost in the Darkness for director Stephen Hopkins, just east of Johannesburg. McLaglen recounts one tracking shot "where we prodded a lion, which was standing over a dummy kill [100 pounds of meat]. When he saw his refl ection in the lens and thought it was another lion, he attacked our camera position— arms and claws sweeping through the bars of the cage trying to get at us. It was actually pretty exciting," says McLaglen, still relishing the adrenalin jolt.

McLaglen's attraction to the craft was perhaps sealed as much by nature as nurture. His family was Hollywood royalty whose roots nearly stretch back to the dawn of the industry. His grandfather, Victor, who aside from winning a best actor Oscar for John Ford's The Informer, also fought heavyweight champion Jack Johnson and en-listed in the British Cavalry at the age of 15 so he could fight in South Africa in the Boer Wars; his father Andrew was a feature and TV director who helmed more episodes of Gunsmoke than anyone in TV history; and his sister Mary is a veteran UPM and producer whose credits include My Cousin Vinny, Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, and The Proposal.

"I grew up on dad's sets and celebrated birthdays with Ethan Wayne [John Wayne's youngest son]," McLaglen says, "so the movie business was all around me. But when I got out of college my dad said, 'Son, this is the beginning of your life, and in order to become a man you have to earn your own living.' I had to react quickly. So, I played the family card and had a door open that has yet to slam shut, thank goodness." In hindsight, McLaglen says he never really considered another path. "It's like being a circus performer," he says. "Getting paid to travel the world with the most incredibly talented and creative people."

And in those travels, for every project since Cast Away, McLaglen has printed up Zulu T-shirts for the crew to help underscore the all-in, team nature of his set stewardship. He chooses to work with filmmakers with huge ambitions because he shares the same aspirations for his own job. "Once Josh buys into your vision as a director," says Hackford, "he'll say, 'Great, go about your business and I'll deliver the set to you,' and you always believe he will."