BY LAEL LOWENSTEIN

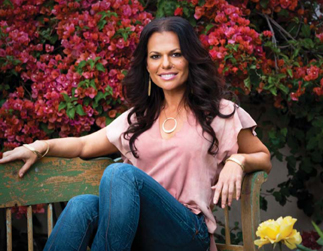

CONFIDENT: Hamri learned her craft by editing and directing rap

CONFIDENT: Hamri learned her craft by editing and directing rap

videos. Her goal is "to have the viewer step inside my mind

and see things through

my eyes." (Photo: Brian Davis)Moroccan-born Sanaa Hamri has spent much of her life proving that rules are made to be broken, prevailing wisdom ought to be tested, and preconceived notions don't mean a thing. The director of Just Wright (released in May), The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 2, and a string of acclaimed music videos, Hamri never took a fi lm class but her experience nonetheless led her to directing. Raised in Tangier by a Moroccan painter father and American mother, she recalls a childhood of art, vibrant colors, and amazing light. "I'd be heading out to play and my father would stop me in my tracks and ask me to take a look at one of his paintings," she says. "My sense of timing, rhythm, and color are all a refl ection of my culture and how I grew up."

After graduating from Sarah Lawrence College with a degree in theatre arts and struggling as an actress, Hamri was working as a receptionist in a postproduction house in New York when she picked up an Avid manual and taught herself how to edit. "Someone told me if you learned to run the machine you could make a couple hundred dollars a day," laughs Hamri. "I was totally sold." While her boss, cinematographer Malik Sayeed, was in L.A. shooting Clockers, she cut a music video on the side and showed it to him when he returned. Impressed with what he saw, he became her mentor and taught her about editing, how to use light and color, and helped her develop the textured, kinetic visual style she would later bring to her work as a director. She started to get jobs editing videos for Hype Williams, Brett Ratner and Mariah Carey, who became another mentor. Under Carey's infl uence, Hamri absorbed useful lessons about the portrayal of female beauty onscreen. "Up until then, I'd only cut male rap videos," Hamri says. "But Mariah had definite ideas about the visuals, about beauty lighting, about which angles she liked, about how to show women at their best."

Also useful was Carey's business counsel—she advised Hamri to raise her rates. "I learned showbiz at top speed in a concentrated amount of time." Hamri also wasn't fazed by the boys' club aspect of the business. As the only girl in her high school class after the one other girl moved away, she was accustomed to male-dominated environments and was the only girl on the soccer team and competed with boys in math and chemistry. Armed with the confidence that came from not knowing anything else, Hamri hardly gave a second thought to the fact she was one of the few women cutting rap videos at the time. "When I go into a room for a meeting, gender is the last thing on my mind. People don't intimidate me," she says.

Before long, and with Carey's encouragement, Hamri was directing videos for artists such as Alicia Keys, Sting, Common, Lenny Kravitz, Mary J. Blige, and later Prince, with whom she discussed artistic freedom. Prince saw her as a breath of fresh air in the business, but not everyone shared that opinion.

As she started to get more offers, particularly for rap videos, Hamri decided to refuse any job that depicted women or people of color in a negative light, and insisted on progressive lyrics. "When [an executive] told me I wouldn't have a career if I turned stuff down, I said, 'Watch me.'" She would later carry the same conviction into her work on features. "What I love about the studios and the producers that I have worked with is that they all want to show positive energy and optimism in films [in contrast to] the feeling that came from working in a music industry where women in general were props in videos and the lifestyle didn't gel for me at all."

When Focus Features approached her about directing the interracial romantic comedy Something New in 2005, she was able to draw on her training as an actor and interweave the disparate strands of her experience and background. Walking on the set the fi rst day, she says, "I realized I was home; things fi nally started to mesh for me."

IN CHARACTER: Samri (center) used her training as an actor

IN CHARACTER: Samri (center) used her training as an actor

in working with (left to right) Paula Patton, Queen Latifah and

Pam Grier on Just Wright. (Photo: David Lee/Fox Searchlight)The film, starring Simon Baker and Sanaa Lathan, challenged preconceptions about race relations, which is what Hamri had in mind when she took the job. In one scene in which Baker and Lathan are having an intimate conversation in bed, she shot the actors with a fi lter so their skin tone would appear virtually the same shade. "I wanted to show that color is the perception of whoever is looking at the object," she says. "We were taking a prejudice and spinning it around." Hamri says her goal as a director is "to have the viewer step inside my mind and see things through my eyes." For her latest fi lm, Just Wright, a sports romance pairing Common (as an NBA player) and Queen Latifah (as his physical therapist), Hamri found that her music video background was helpful in giving the basketball sequences a fluidity and natural rhythm.

Working with a basketball coordinator, she mapped out her favorite plays and shot using four cameras. "I also designed a few specialty shots: 360 degrees around the players with ramping speed changes as well as body cams. I had a vision of cameras attached to the players. I wanted to make sure I captured the essence of movement."

Rather than storyboarding, she prefers to spend time with the DP discussing the shot list. She filmed Just Wright in sequence as much as she could to "make things as easy as possible for my actors." That meant assembling the cast for a table read and allowing for a rehearsal period that involved improvisational and trust exercises. "All of my training has given me the language I need to communicate with my actors because I know what it feels like to put yourself out there and create a character. As their director, I am their leader, teacher, best friend, sister, and parent all wrapped up in one. I try to be the director I would have wanted as an actor." For Hamri, preparation is one of the most vital aspects of her job—and the key to avoiding misunderstandings down the road. When she goes for a meeting to discuss a project, she puts together a detailed presentation. For Just Wright, she arrived bearing a 40-page book including a collage of newspapers, magazines and photos that described the look and tone of the film.

"I showed the style of locations I would use— the interiors of houses, the exteriors of New York—the type of basketball shots I loved, the clothes the women would be wearing, as well as the NBA player lifestyle. I did a lot of research and put it together in a cohesive fashion in order for the producers and studio to see my vision for the film." By the time the cameras start rolling, Hamri has virtually cut the fi lm in her head, so there is very little extra footage and no deleted scenes—much to the disappointment of the studio's home entertainment division. But because she's laid so much groundwork beforehand, that may be the only point of contention Hamri has with studios. "No battles, only notes," she says—though she acknowledges once in a while there may be a difference of opinion over a scene's placement or function. Whenever that happens, Hamri will patiently explain her perspective to the studio. "I believe in conversation," she says. She usually gets her point across, and if she doesn't, she's philosophical about it. "They take the note or they don't. But I move on; I see the bigger picture. It's a learning process.