BY RICHARD SCHICKEL

Josef Von Sternberg, then one of Hollywood's top directors,

Josef Von Sternberg, then one of Hollywood's top directors,

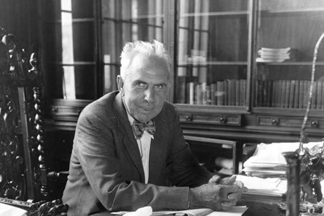

did not believe in Dreiser's fatalism. (Credit: Everett)

One day in 1930 "a corpulent eagle," as the director Josef von Sternberg described him, swooped down on Hollywood, wrapped in a cloud of mistrust bordering on disgust. That big bird was Theodore Dreiser, the preeminent American naturalistic novelist, and he carried in his luggage a screenplay based on his masterwork, An American Tragedy, which Von Sternberg had agreed to direct, but which Dreiser thought was inadequate to his book's grand design.

By now, this project had become one of those messy imbroglios—full of false hopes and false starts—that have ever been a feature of movie life. And it was on its way to becoming a test case, in the full legal sense of the term, of a studio's right to radically alter, if not downright travesty, any literary property it acquired. The rights in question began with a studio's untrammeled ability to devise a script that revised not just the original writer's words, but his larger intentions, and it extended to inappropriate casting and the wrongheaded choice of director—all things that happened to An American Tragedy as it limped its way toward production and release. Putting the point simply, the court decision in the case Dreiser eventually brought against the studio for tampering with his novel, is the sole—and very obscure—precedent that guarantees to this day everyone's right—studios, writers, directors—to do what they will with any literary property once screen rights to it have been purchased.

This case did not really break new legal ground, but it did confirm what had up to then been standard studio operating procedure when it came to the purchase of literary material. For the moment, the novelist's wary attention was fixed on the arrogant and dismissive Von Sternberg, who was, at the time, the movies' most romantic and visually arresting director, the man who had made perhaps the most exciting passage from silent to sound production. He was then taking a brief hiatus from the successful string of pictures (The Blue Angel, Morocco, Dishonored) he had made with his discovery and lover, Marlene Dietrich, who had decamped to Europe. Under contract to Paramount, Von Sternberg was available and this was a potentially prestigious project for the studio's most heralded director.

Von Sternberg professed the highest regard for Dreiser's work though privately he thought less well of it, perhaps because it offered him so few opportunities for the kind of poetic imagery on which his reputation rested. Whatever he was, Von Sternberg was very far from being a realist, let alone a naturalist. He also thought that Dreiser was being notably ungrateful to the movies, and here he had a case. The writer's first novel, Sister Carrie in 1900, had been sabotaged by its publisher, and in its first years of public life had earned Dreiser less than $200 in royalties. His subsequent novels had not done much better, earning him a reputation as a clumsy stylist, though an often-powerful moralist. Why An American Tragedy, published at the height of the jazz age in 1925, the same year as The Great Gatsby, so radically reversed his fortunes, is still hard to determine. Based on the true story of a luckless, feckless young man called Clyde Griffiths in the novel, it is the account of how he perhaps unintentionally murdered a young factory worker named Roberta Alden, whose pregnancy inconveniences his rise, both professionally and romantically, and in particular his prospering relationship with a rich young woman of high social status.

Possibly the book's success had something to do with the postwar generation's impatience with an older era's gentility and evasiveness. It was ready for a book that, for instance, openly discussed abortion as one solution to Clyde and Roberta's problem. The conventional opinion, of course, was that it was never, ever going to be a movie, especially since the studios had lately appointed starchy Will Hays, a Midwesterner, Republican, and former Postmaster General as the industry's chief censor and guardian of morality.

The doubters, however, had not reckoned on the power of the press, specifically a New York World columnist named Quinn Martin who wrote that Tragedy "if courageously treated would make the greatest film yet produced." Others had been whispering similar sentiments into the ear of Jesse Lasky, head of the Famous Players-Lasky (predecessor to Paramount), who, like many moguls of the day, was almost as eager to establish movies as a legitimate expressive form as he was to make money.

Phillips Holmes takes Sylvia Sidney on a ride she won't come back from in

Phillips Holmes takes Sylvia Sidney on a ride she won't come back from in

An American Tragedy. (Credit: Paramount/Everett)

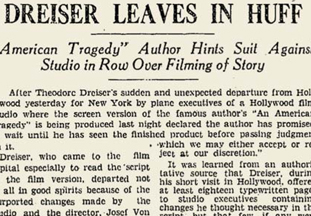

When Von Sternberg's film departed from his book, Dreiser filed a

lawsuit to block distribution. (Photo Credit: UPenn Library)

So, very quickly, an unprecedented deal was made, with Dreiser receiving $90,000—a record price—for his novel. But no script was written for the next four years, in part, no doubt, because Hollywood was so preoccupied with making the transition to sound. This transition was perhaps An American Tragedy's movie salvation. Silent pictures were such a poetic medium, and it was such a harshly realistic book. Just right, someone eventually thought, for Sergei Eisenstein. The Russian master of revolutionary spectacle had arrived in the United States to try to makes movies here and Paramount was courting him. Dreiser's novel was actually not ideal material for Eisenstein either, lacking as it did those elements of panorama and triumphalism that had marked his previous work, most notably Battleship Potemkin.

Still, it certainly offered a communist director a stern critique of capitalism and it was obviously a major literary work, to which a director of his stature was well-suited. Not so fast, said Dreiser. He had sold Paramount only the rights to a make a silent film. If they wanted the film to talk, a new deal would have to be negotiated. So another $55,000 flowed into the writer's pocket and together with a writer named Ivor Montagu, Eisenstein set to work on a script. They and the studio intended the film to be long, expensive and "prestigious." Moreover, it appears that their script was mindful of Dreiser's naturalistic principles, which argued that our fates were determined not by our own ideas and actions, but by the workings of blind, malevolent social and economic forces. The script was long (173 pages) and had some passages that were more Joycean than Dreiserian in its presentation of Clyde as more a victim than a criminal. It was judged by the studio as dangerously subversive, or as studio executive B.P. Schulberg put it, "a monstrous challenge to American society." Perhaps more damningly, Paramount was in receipt of letters from radical rightists hysterically condemning it for hiring a Russian communist to direct the film. That was given as the cause for Eisenstein's abrupt firing.

Still, "Hooeyland," as Dreiser had taken to calling Hollywood, had incurred development costs on the project of a half million dollars and had nothing to show for them. Which is where Von Sternberg and a writer named Samuel Hoffenstein, who was known to Dreiser socially, enter the story. All talk of naturalistic principles aside, there was at the core of An American Tragedy, the story of a blighted romance and something of a murder mystery (did Clyde actually drown Roberta or did he have a last-minute change of heart and attempt to save her? If the latter was the case, was he morally guilty if legally innocent?).

There was another way of looking at the narrative. It might be, as a Paramount screenwriter put it, that it was just a story "of a guy who got hot nuts, screwed a girl and drowned her." That, finally, is pretty much the line Hoffenstein and Von Sternberg took, scanting—though not entirely eliminating—Clyde's back story as the child of religious fundamentalists, replacing as he grows up primitive religious beliefs with a vague and amoral belief in "getting ahead" in the standard American way.

It was this script that Dreiser and Von Sternberg fell to arguing about, with the writer pointing out vulgarisms in the manuscript and the director coolly showing him passages in the novel from which this material had been lifted without change. In these exchanges Dreiser was relying on a clause in his contract that granted him the right to offer "comments, advice, suggestions or criticisms" with the company promising to "use its best efforts" to accommodate.

Who knew that the "best efforts" scam, a casual legalism that applies to matters not solely confined to literary adaptations, had such deep and ancient roots? All we know for certain is that Von Sternberg thought that all Dreiser's talk about the naturalistic forces shaping this tragedy was—well, a lot of "hooey"—vague, undramatic, and as the director said, "far from being responsible for the dramatic accident with which Dreiser had concerned himself." He would make a story of crime and punishment, nothing more and nothing less. This he proceeded to do, on a scale and budget far less grand than Lasky had originally imagined.

Von Sternberg would later call the film "a little finger exercise," and that, indeed, was what it proved to be. His picture is nowhere near great, beginning as it does with the pious dedication: "To the men and women who have tried to make the world better for youth." In his cheeky autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, Von Sternberg would argue that "literature cannot be transferred to the screen without a loss to its values; the visual elements completely revalue the written word." But still, that's precisely what he failed to do in this instance. Aside from a few moody shots of wind-blown trees, the film is shot in a flatly realistic manner, with none of the often startling imagery for which Von Sternberg was at the time justly famous. Worse, he was cursed with a blond, blue-eyed, bland leading man named Phillips Holmes, who was incapable of any emotion beyond a slightly fluttering panic as his fate closes in around him. The one thing the film has going for it—and it is a great deal—is Sylvia Sidney as Clyde's victim. She was a serious and spirited actress, and here, as elsewhere, brought to her roles a hopeful energy that belied her drab circumstances.

You can't help but like her and root for her, even though you know her fate long before she or her killer does. Her sheer likeability decisively shifts the ground of this movie; she, not Clyde, is where our sympathies quickly gather. You have only to compare her work to that of the whiny Shelley Winters in the same role in George Stevens' much more heralded remake, A Place in the Sun, to understand her contribution to this movie.

The poor young man (Holmes) wants the rich girl (Frances Dee) in An

The poor young man (Holmes) wants the rich girl (Frances Dee) in An

American Tragedy (Credit: Los Angeles Times; Paramount/Everett)

Indeed, one wonders if, in some dim way, Dreiser grasped her instinctive subversion of his work. That, however, is not where his wrath centered. He put the matter this way: "I have a literary character to maintain and I contend that I have a mental equity in my product. Even though [the studios] buy the right of reproduction, they don't buy the right to change it into anything they please." So saying, he ordered his lawyers to seek an order enjoining the studio from distributing the film. "I feel, in a way, that I am acting for the thousands of authors who haven't had a square deal, in having their works belittled for screen exploitation."

Dreiser was exercising what we now refer to as his "moral right" to protect the integrity of his work. His lawyers warned him that he had little chance of success, and they were right. The case was heard in New York State Supreme Court in White Plains, where the studio's lawyers charged Dreiser with plagiarizing the trial record of the actual case on which he based his novel. "It's a lie," the writer shouted, for which he was cautioned by the judge, one Graham Witschief.

Dreiser's lawyer, Arthur Garfield Hays, early in his distinguished career as a civil liberties lawyer, quite reasonably asked that if that were the case, the studio might have done the same thing. Hays understood that the studio wanted, for purposes of prestige and publicity, Dreiser's name attached to the film. The ending of the case was nasty, brutal and short: Witschief ruled that "in the preparation of the picture the producer must give consideration to the fact that the great majority of the people comprising the audience before which the picture will be presented will be more interested that justice prevail over wrongdoing than…the inevitability of Clyde's end..."

So much for naturalism as a high principle. So much, as well, for writerly integrity in a cash-and-carry society. But Dreiser, who would soon join the Communist Party, was not entirely unconsoled. He had fought the good fight—one that, curiously enough, had never before been waged in court, and has not been waged since. In the early days of the movies, film versions of very famous books and plays had been blithely expropriated without permission or payment. Later, perhaps because silent films were such an inferior method of conveying literary materials, writers had simply taken the money and run, on the grounds that a silent film could not possibly approximate the force and/or subtlety of their original work. It required sound to more fully—if never perfectly—convey a writer's intentions.

Von Sternberg was not present in Judge Witschief's courtroom and made no subsequent comment on the case. Indeed, by that time he was completing his best sound film, the delirious Shanghai Express. However, in a matter of about three years the taste for his (and Dietrich's) exoticism faded and his career became sporadic. The same was true of Dreiser: He became more of a cranky spokesman for left-wing causes than a working novelist. The case Dreiser brought against Paramount confirmed the studio's right to screen authorship—definitively taking it away from the writers of the original material. The studios, of course, had the right to transfer their "authorship" to directors like Von Sternberg who had the clout and the will to impose their visions on whatever material came to hand. Von Sternberg's inability to find a way to do that in An American Tragedy bespeaks, more than anything else, the unsuitability of the material for his artistic sensibility. That he so quickly asserted his unique, giddy, delicious style in his next films proved that "auteurship" could be asserted by directors—as long as their work remained profitable for the studios. But it would be decades before the rise of the auteur theory encouraged the studios to at least pay lip service to that fact. But there's one more irony to contemplate in this tale.

Two years later, Dreiser sold the film rights to another of his novels, Jennie Gerhardt, to Hollywood, receiving payment of $25,000 plus 7 percent of the profits. The buyer was—well, yes—Paramount Pictures and the star was—well, yes—Sylvia Sidney, playing—well, yes—a woman dealing with an unwanted pregnancy. Dreiser did not like that film either, though it had, in general, a better cast and a more sentimental tenor. He protested to Eisenstein, with whom he had remained friendly, that "he was thoroughly disgusted with the motion picture industry over here," not only because of the way his work had been treated but "because of their cheap commercialism and toadying to the lowest and most insignificant tastes." About that there was nothing more he could do. The matter had been settled quietly, but firmly and forever, in a suburban New York courthouse, two years earlier.