BY GARY GIDDINS

(Credit: Everett Collection.)

(Credit: Everett Collection.)

The word "rangy" might have been invented for John Huston: all limbs, no waist, a long, lined face like a derelict prophet. The word also indicates his need for the itinerant realism that led him to make films in San Pietro during a war, the Congo, Mexico, Wales, the Canary Islands, Ireland, Japan, Rome, Helsinki, Tobago, Morocco, and Vienna, as well as Reno, Macon, and Stockton. And it also clarifies his attitude toward filmmaking, in the latitude he offered writers, cameramen, and actors especially—stepping in when necessary and otherwise allowing plenty of romping room or, if the neck fit, rope.

Of the larger-than-life directors in American film lore, none was more cantankerously independent, innovative, and reckless than Huston, whose virile storytelling often seems inextricably bound to a personal legend expounded in a raft of novels, plays, and memoirs by and about him. The 1950s alone—the period when he made the transition from studio director to the first truly autonomous, international director—generated at least nine works in which a key character is based on Huston or a disguised version of him. By far, the most ink was spilled in recollections of The African Queen (1951), which Paramount has restored for DVD and Blu-ray discs that rank among this year's very best. In fact, the restoration is so effective you can hardly miss the shadow of a boom creeping along the rim of the African Queen's hull. Yet this is but a smudge in a film that is thoroughly, ravishingly verdant—a Technicolor triumph, pitched by cinematographer Jack Cardiff at a nexus between reality and sunstroke. Huston's mobility and his uncanny sense of place and timing create an alien terrain as dodgy and dreamy as the eccentric love story it enfolds. The African Queen violated two abiding Hollywood traditions: it rejected the backlot Africa of Tarzan for the Ruiki River in the Congo, and dispensed with youth and glamour in favor of middle-aged movie stars looking every inch the worse for wear.

Only after the camera began to roll did Huston realize that the sparks between Humphrey Bogart's scruffy skipper Charlie Allnut and Katharine Hepburn's censorious spinster Rose Sayer might distill a colorful but predictable exploit into a unique comedy, introducing a new tonality in his work. For the first time, Huston jettisoned arch repartee for the collusive innocence of polar opposites, a situation he continued to explore in such films as Moulin Rouge (1952, painter and whore), Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison (1957, marine and nun), and The Night of the Iguana (1964, defrocked minister and spinster). With this realization, he told his leading lady that her Rose was too severe, and suggested she bear in mind the forbearing smile of Eleanor Roosevelt. Hepburn later recalled that as the finest piece of direction she ever received.

Huston also decided that, unlike the adventurers doomed to failure in The Maltese Falcon (1941), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), We Were Strangers (1949), The Asphalt Jungle (1950), and The Red Badge of Courage (1951)—all available on DVD, along with other films mentioned, unless otherwise noted—Charlie and Rose in The African Queen would prevail, blowing up an impregnable German warship. The ending might be absurd (a word bandied by Charlie and Rose), but it would be better than happy; it would be blissful.

The audience is primed to root for the picture from the first shot,partly hidden by the credits and set to ambient jungle sounds: a marvelous zoom through dense foliage into a clearing where a missionary leads the natives in song. The mean little trawler known as the African Queen is introduced not by the long shot indicated in the published script by Huston and James Agee, but by the sound of a steam whistle shown in a close-up and resembling, with its mouthlike aperture, an animated character. The comical tone is thus instantly implied and amplified as the camera descends to show the basking Mr. Allnut, drink in hand, serenaded by a native boy playing the kalimba. For a second, the boy breaks the fourth wall, looking directly at the camera. We are not in Hollywood anymore.

Huston spent much of his life escaping Hollywood—or undermining it. When he was born in Missouri in 1906, his parents were on the verge of divorce. His father Walter Huston would not achieve Broadway stardom for nearly two decades, and his mother, a journalist, took John to Los Angeles, where he dropped out of school at 15 to take up painting, fighting, and horses—all steady influences on his film work.

He made his name at Warner Bros. as a scriptwriter, with impressive credits: Jezebel, Juarez, Dr. Ehrlich's Magic Bullet, Sergeant York, High Sierra. In 1941, Huston convinced the studio to let him direct. The project was hardly promising: Dashiell Hammett's The Maltese Falcon had been filmed poorly twice and belonged to the discredited second-feature genre of detective stories.

The Maltese Falcon remains one of cinema's great directorial debuts. In his novel White Hunter Black Heart, Peter Viertel has his Huston-like director attribute his breakthrough to a "melodrama with a guy who'd always played heavies, and I made him play a hero." Yet it did far more than make Bogart a major star, while reviving the fortunes of Mary Astor and Peter Lorre and introducing the unlikely box-office attraction of the 1940s, Sydney Greenstreet. It remade the detective film with an authority worthy of Hammett. The form had fallen into a sinkhole of clichés: eccentric detectives, baleful comedy, dim cops scratching their heads as the private shamus explains the facts. Huston's stylish dedication resonated with moral ambiguity, sexual tension, and knowing wit. He improved on Hammett's one misstep—a pulpy strip-search—with a neat bit involving a palmed bill. His control of the cast, camera, and setting reached its apex in the final half hour, set almost entirely in a living room.

The following year, Huston reunited Bogart and Astor in Across the Pacific (1942), but abandoned them in the last reel for an Army commission that took him to the Aleutians. His war documentaries are among the most powerful ever made, especially San Pietro (available on the DVD of a non-Huston programmer, Surrender—Hell!) and a long-suppressed look at battle fatigue, Let There Be Light. His return to Hollywood took a detour to Mexico for The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), earning his father and himself Oscars, and turning the Warner Bros. style inside out. He shot Bogart as a filthy murderer and the dignified Walter Huston as a toothless prospector, giving the most memorable line to Mexican actor Alfonso Bedoya: "Badges? We don't need no stinkin' badges!"

(Credit: AMPAS)

(Credit: AMPAS)

(Credit: Warner Bros./Everett)

Key Largo (also 1948) shrewdly transformed a dated play into an examination of postwar guilt, mistrust, and vice. He introduced Edward G. Robinson's gangster in a steamy bath (Huston described the image as "a crustacean with its shell off"), and forced alcoholic moll Claire Trevor to warble for a drink, revealing a soul-bearing desperation (Huston insisted on shooting without rehearsal) that won her an Oscar, too. We Were Strangers (1949), involving the unpopular theme of Cuban freedom fighters, died at the box office but merits a DVD revisit. Its existentialist ironies prepared Huston for directing the Broadway debut of Jean-Paul Sartre's No Exit. In Sartre, he had found a soulmate in depicting a godless universe where men express defiance but rarely experience grace. The Asphalt Jungle (1950) proved to be a nearly impeccable illumination of that dilemma, inventing the modern heist film in the bargain. Each character works on the wrong side of the law, yet the usual social mores and moral quandaries abide, defining their individual fates. That film's success couldn't protect The Red Badge of Courage from MGM's demolition, though that film retains many visually stunning moments, as well as the ironic casting of Audie Murphy, the most decorated GI of the Second World War, as a coward. Huston's response was to embark on a new career outside Hollywood, beginning with his sojourn in the Congo for The African Queen.

Following that, working with his favorite cinematographer, Oswald Morris, Huston experimented with color processing in Moulin Rouge, a film that, despite its glorious cancan opening, is the most relentlessly downbeat in his oeuvre. His existentialist bent took flight in a droll romp of futility, Beat the Devil (1953), and in his bravura assault on God and commerce in the guise of a white whale. Moby Dick (1956) is a flawed but sumptuous adaptation of an inadaptable work. The DVD captures the etchinglike effect that Huston and Morris created by combining color and monochrome negatives. If the tempo is occasionally uncertain and the whale a carnival float, the film is one of the few epics that feels epical, not because of countless extras and special effects (Moby Dick has neither), but because the material is made to soar.

After the popular two-hander, Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, Huston, now living in Ireland, continued traveling, but his career hit a long slump. Despite memorable images and abiding themes of race and ethnicity, his late-'50s and '60s films were often flat and uninvolving. The most promising of them, Freud (1962, not on DVD), began as an alliance with Sartre, who wrote an ingenious but unfilmable script. The film faded at the box office, yet Huston's narration, read with his deliberate cadences and lazy vowels, initiated a second front for him as an actor, culminating in 1974 with Roman Polanski's Chinatown. Meanwhile, Huston's directing was stalked by rumors of inattention. He was caught napping or doing crosswords on the set. He wasted years on The Bible (1966) and appeared removed even in good work, including The List of Adrian Messenger 1963), a film about a mass murderer that, except for its jocular tone, anticipated the chaos of the period; The Night of the Iguana (1964), with its superbly droll prologue before succumbing to Tennessee Williams dramaturgy; and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), an hysterical gothic fairy tale in which Marlon Brando whips a horse and is in turn whipped by Elizabeth Taylor—all because he desires a soldier who prefers Taylor's lingerie.

Then he made his way back up the mountain. The first step was The Kremlin Letter (1970, unreleased on DVD), an audacious exercise in sustained paranoia that lost money but showed a renewed sparkle. In 1972, Huston took a small crew to Stockton, California, to turn Leonard Gardner's boxing novel, Fat City (not on DVD, but reportedly in the works) into a measured masterpiece, exploring a strata of American life never shown in movies. Suddenly he seemed once again to be reveling in visual invention and an unerring sense of tempo. Not everything that followed reflected his renewal, but an outpouring of great films, unlike anything he'd done before, added up to an unparalleled directorial comeback. Huston's flexibility actually flourished as he passed 70. He made gemlike art films (Wise Blood, 1979, Under the Volcano, 1984), the funniest and most subversive of Hollywood mafia films (Prizzi's Honor, 1985), and, at 81, an elegiac transfiguration of Joyce's The Dead (1987), released four months after his own death.

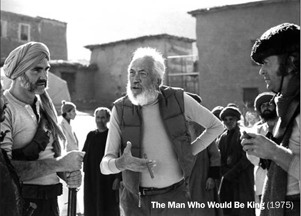

But if one had to choose a single moment to signify Huston's adventurous life and work, it might be a scene from The Man Who Would Be King (1975), his most majestic escapade—a tour de force for Michael Caine and Sean Connery that improved on Kipling's story with Hustonian humor. Midway in the film, his two characters Peachy Carnehan and Daniel Dravot have reached an apparent endgame, backed by snowy cliffs and facing an uncrossable chasm. Accepting the absurdity of their imminent death with bravado, they laugh uproariously—thereby triggering an avalanche that fills in the chasm. As Huston often did, they shrug and move on.