BY TERRENCE RAFFERTY

Photographed by Don Arnold

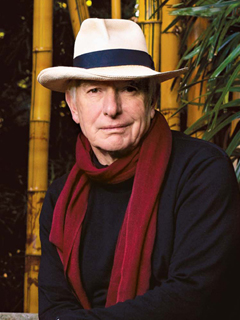

There hasn’t been a new film by Peter Weir for seven years, but that’s about to change, with a picture titled, aptly, The Way Back. The movie, which stars Colin Farrell and Ed Harris, is about a group of prisoners who escape from a Soviet prison camp in 1942 and trek to India. And as I talk to Weir—who lives in Sydney, the city of his childhood—it’s hard not to think about what a long, strange trip his career has been, from its beginnings in a virtually nonexistent Australian film industry in the 1970s, to two decades of great success in Hollywood, and now to this odd, unsettling 21st-century movie world in which an acclaimed director still in his prime at 65 has to struggle to get a film, any film, onto the screen.

There hasn’t been a new film by Peter Weir for seven years, but that’s about to change, with a picture titled, aptly, The Way Back. The movie, which stars Colin Farrell and Ed Harris, is about a group of prisoners who escape from a Soviet prison camp in 1942 and trek to India. And as I talk to Weir—who lives in Sydney, the city of his childhood—it’s hard not to think about what a long, strange trip his career has been, from its beginnings in a virtually nonexistent Australian film industry in the 1970s, to two decades of great success in Hollywood, and now to this odd, unsettling 21st-century movie world in which an acclaimed director still in his prime at 65 has to struggle to get a film, any film, onto the screen.

Weir would probably consider this view of his recent travails a little melodramatic. He’s a very modest, almost self-deprecating man, entirely disinclined to take himself too seriously. His lack of self-importance is a pretty impressive trait, considering that no fewer than four of his films have earned him nominations for best director from both the Directors Guild and the Academy: Witness (1985), Dead Poets Society (1989), The Truman Show (1998), and Master and Commander (2003). Out of a dozen previous theatrical features, it’s an all-star’s batting average.

As with any good artist, the apparent contradictions of his own nature strike him not as problems but as opportunities. They excite his curiosity—which is enormous—and spur his explorations. His speech is soft, very gently accented, slightly quizzical, and he weighs every question seriously, as if he’d never considered it before. He has no practiced answers, no well-worn raconteur’s anecdotes. Weir has made films on five continents, but wherever he travels, he always seems to find a way back to his beginnings.

TERRENCE RAFFERTY: Let’s start with your new film, The Way Back. What was it like directing again after such a long layoff?

PETER WEIR: It comes back fairly quickly. When you come to the shooting side of it, you never really get used to that, I don’t think. It’s the marathon it always was, but after aweek you’re into it. It’s the time pressure that takes getting used to again.

Q: Was it a difficult shooting schedule?

A: It was pretty tight, something like sixtythree days, and with a lot of location work, a lot of moving around, and a large cast, six or seven of whom were on screen almost all the time. It had its challenges.

Q: Is it much harder to get a film made these days?

A: It’s changed out of sight. It’s completely polarized, with the middle ground largely gone. People are making fi lms for under 15 million in the independent world and even then there are fewer slots than there are films. The budget for The Way Back was 30 million, which is the head bumping the ceiling, I think. That’s as much as anyone would want to spend these days for a non-studio picture.

Q: With locations all over the globe and a fairly modest budget, I’d guess that The Way Back doesn’t have the amount of special effects work that Master and Commander had.

A: Oh, nowhere near. Master and Commander was a film that just couldn’t have been made without the ability to create environments artifi cially. In The Way Back it made more sense just to go to the environments. We shot mostly in Bulgaria, standing in for Siberia, and Morocco, which played the part of Mongolia and fi nally India. We did use CGI for the Great Wall of China.

Q: And that kind of location shooting wouldn’t have worked for Master and Commander?

A: I’d read all the books about shooting at sea, and I made the decision early on that we wouldn’t go to sea for anything but a short period of time. I think it wound up being 10 days out of the whole shoot. Everything else was in the tank, using miniatures and CGI, which is great for the ocean and the sky. The story was fairly slight, so the movie pretty much depended on the audience enjoying the feeling of being at sea, believably.

Q: Why did you decide to use miniatures?.

A: Initially I was going to do it purely CG. But having seen the first Lord of the Rings I got in touch with Peter Jackson, who put me on to [special effects artist] Richard Taylor, and that was a very fortunate call. We shot miniatures in the Weta Workshop in Wellington. The two vessels were built on a very large scale, 20 to 25 feet for the Surprise. Beautiful work. The miniatures added reality that we couldn’t have gotten with CG. I also had Rob Stromberg, a remarkable artist, whom I used to call my CGI bodyguard; he went to every meeting with me, in addition to doing his own work. He’s gone on to great success in Avatar and Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland. He comes from the world of matte painting, and has a terrifi c understanding of scale, which is really important in work like this. Wide shots can be especially tricky, when you get a panorama of what’s supposed to be a setting from the past—there can be too much detail, it can look too perfect. Rob understands how to make it look real. You know, the cameraman never gets the perfect day, in reality you never find the perfect spot for your wide shot. Rob knows how to build imperfections of various kinds into a scene, maybe a slight obscuring of something, to give the sense that the camera really was there.

Q: Did anything in your early films prepare you for this kind of filmmaking?

A: I came up in the ’70s, which was an era of getting out of the studio. Not that we had studios here, really. In a sense we’ve all returned to the studio. Doing Master and Commander was like going back to school. I did 12 months of post. Some of the editors worked through animatics, but I found that awkward and unsatisfactory, because I was depending too much on the technicians beside me. They’d say, ‘What do you want? You can do anything, put the camera anywhere you like.’ It’s almost too much choice. I found what worked for me was to stage scenes on my office floor with little models of the ships. I’d use a lipstick camera to shoot sequences on the floor, then have my editor cut those sequences and give them to the CG team to follow. It was pretty hokey for such an expensive production, but it was the way I felt I could remain in control.

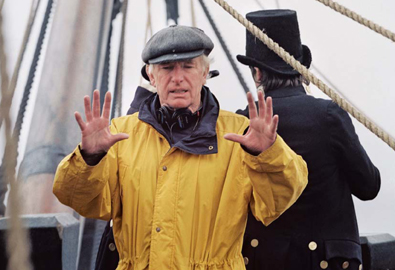

MOMENTS IN TIME: Weir shot his latest film, The Way Back,

MOMENTS IN TIME: Weir shot his latest film, The Way Back,

on locations in Bulgaria Morocco and India.

Weir thought Jim Carrey was the only man for the job in The Truman Show.

Weir thought Jim Carrey was the only man for the job in The Truman Show.

Weir shot only 10 days at sea for Master and Commander.

Weir shot only 10 days at sea for Master and Commander.

(Credits: Paramount; Simon Varsano; 20th Century/BFI)

Q: Do you do a lot of storyboarding?

A: I did on that picture, and some on the new one. But I never really enjoy it. I’m probably a victim of my experience, which is standing beside the camera on location. And I like to make changes on the day, even in action sequences. Which probably has something to do with my background in sketch comedy, where you had to ad-lib, to change things constantly. If you’ve cast a picture right and you don’t have script problems—those are the two essentials—then on the day you have this little piece of life in the story you’re telling and anything can happen.

Q: How did you move from writing and performing comedy to directing movies? Did you always want to be a director?

A: I didn’t know what I would do, as long as I was going to be in the business. I did make some film clips for TV comedy shows, which is what led me into film.

Q: What was the Australian film industry like when you were breaking in? Your first film, The Cars That Ate Paris, came out in 1974, and although it’s nicely directed, I get the impression that the talent pool of actors was fairly shallow.

A: In those days you couldn’t really count on anybody over about 25. If you had characters in their 50s, they’d turn up with these freaky voices, because their backgrounds were in radio and theater. In my early films I was constantly cutting dialogue, just because it sounded so bad, and having to come up with visual ideas that would convey the character.

Q: Bad acting as a spur to creativity?

A: Exactly. In my cutting room even to this day, after the first cut or two I’ll watch my film silent, to get to know it, to see what’s coming over without dialogue.

Q: Your second movie, Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), had a somewhat bigger budget, and it showed more of what you could do visually, your sense of composition. Did you have any art training?

A: There was really no culture here when I was growing up. No great collections of paintings, and very little in the way of philanthropists, such as in your country, who would take their ill-gotten gains and spend it on art as their way of atoning. It sounds curious to say, but the landscape, nature itself, was probably the biggest influence on me, particularly being here in this great empty country and living by the sea as I did. I think that was my art gallery. It was an era when children were always ordered outside, and you could just wander off, go down to the bay. Boredom can be a tremendous advantage for anybody with imagination.

Q: It must have been good to have a bit more money for Picnic at Hanging Rock.

A: The budget was about $450,000, I think. But you never have enough time and you never have enough money. What was really the driving force in that film was that I had no ending, and had to prepare the audience for that or I’d lose them completely. It was a kind of whodunit, where the audience would normally expect to have everything explained at the end of the picture. So the problem is how to get them in a different kind of mood, how to unsettle them so they would begin to feel this is not an ordinary whodunit—that something else is coming. I’d read somewhere that there are certain primal sounds that are in a way in our DNA, because they’d been experienced before by humankind, and one of those sounds is an earthquake.

Q: Have you ever been in an earthquake yourself?

A: I’ve been in two, one of them in Manila when I was working on The Year of Living Dangerously (1982). The sound is indescribable. So, going back to Picnic at Hanging Rock, I got hold of a recording of an earthquake, and we experimented with the optical soundtrack so that it would register but you wouldn’t be able to identify it as the sound of an earthquake. We slowed it down a little, and I’d use that sound sometimes in sequences where there was no reason to expect anything like that—in a landscape or even in an interior shot, where I’d add it to the natural sounds outside the window. It would just register as a low rumble, indistinct. It really only worked in optimum sound systems, but I do think it contributed something. And I did it in my next movie, The Last Wave, too. I knew I’d scored when someone coming out of that picture said to me, ‘There were odd moments when I felt a really eerie, creepy feeling and I couldn’t tell quite where it was coming from.’

Q: Secrets of the horror masters…

A: And I’ll tell you another technique that creates an uncanny feeling, and that’s whispering, when you can’t make out any particular words. The very idea of whispering—it’s conspiratorial, it suggests things that cannot be spoken fully aloud. And it’s an odd sound. So I’ve sometimes dropped it in, though it has to be used, like the earthquake sound, in a kind of contradictory, nonliteral way. I use it as an ingredient, rather like a chef in the kitchen. What’s that in your sauce? [laughs]

Q: You took on some real, historical horror in Gallipoli (1983), about a World War I battle in which a lot of young Australians lost their lives rather senselessly. What made you want to make a fi lm about that national tragedy?

A: Part of the reason, I think, was a quote from Ingmar Bergman, who once said something like: ‘You can do anything onscreen but kill someone. Disbelief will not be suspended.’ And when I thought about fi lms in which I’d seen people die that seemed to me largely true. So I thought I’d have a go at doing it, at being the exception to that statement. The first thing I decided was that I wouldn’t show much blood and gore. I was criticized for that later, that I hadn’t shown the full horror— limbs blown off and so on. But I thought if I did that I couldn’t kill someone convincingly, that the audience would just be thinking about special effects and makeup. Even at the last moment, when I show the death of the character Archy, whom we’ve gotten to know, you don’t see any blood, really.

Q: Gallipoli was a much larger-scale film than either Picnic at Hanging Rock or The Last Wave.

A: It was expensive for an Australian film of that time, but the budget was only about 2 million and we had to be careful how we spent it to give the audience something of a spectacle. So we went to Egypt for some scenes of the soldiers playing football around the pyramids. Which of course makes you smile today, because you’d just CGI it. In those days, you had no choice but to go there. We shot the battle scenes in South Australia; the army helped us by supplying 600 troops for a brief period, for the wider shots.

Q: Did you shoot the battles with multiple cameras?

A: No, that was less common then.

Q: Would you do it that way now?

A: I think most directors today work with two cameras pretty much all the time. But as you start, so you end. I think I’m a one-camera person principally. And I do still prefer to stand beside the camera rather than work from a monitor, which probably shows my age, too. I learned to pick up the nuances from watching beside the camera rather than looking at a screen, and then to look at dailies. It’s a process that still works for me.

Q: Do you ever use the monitor?

A: The film that forced me to do it was Master and Commander, because of the cramped spaces on the sets and the real vessels. I wanted those spaces built to real measurements. And I don’t float walls much, again from the prejudice of the nonstudio, location shooting of my early films. So I just couldn’t get in there, and I had to watch the monitor. But I find it frustrating. I much prefer to stand next to the camera not just while the shot is being taken, but when it’s being set up, to work with the camera operator and spend as much time looking through the eyepiece as I can. I think working from the monitor can affect your framing, and affect your understanding of the theatrical experience.

FAR FROM HOME: Weir directing Richard Chamberlain in

FAR FROM HOME: Weir directing Richard Chamberlain in

The Last Wave.

With Mel Gibson on The Year of Living Dangerously.

With Mel Gibson on The Year of Living Dangerously.

(Credits: (top) Kobal Collectoin/ (bottom) Warner Bros./ Everett Collection)

Q: The camera operator on Gallipoli, John Seale, became your cinematographer a few years later, for Witness.

A: One of the fortunate things about Gallipoli was it was a period when the industry had begun to come to life, in the late ’70s. In this period we still had only two crews that could be assembled at any one time. If three pictures were shooting, somebody was in trouble. And two crews is probably generous. More like one and a half. Russell Boyd was the cinematographer, and John Seale was about ready to go off on his own as a DP. But a lot of people took less money or delayed promotions to do that film, because there was a feeling it was going to be a special film. Which is always a kind of tyranny, because odds are it won’t be. But the result was that I did have a particularly fine crew, the best that could be put together in the country at that time.

Q: Two crews in the whole country? The technical personnel was really that sparse?

A: You couldn’t really fire anybody, because it was very much a frying pan/fire situation. So you had to learn how to bring out the best in someone. If somebody wasn’t cutting it, you just had to sit down with them.

Q: You’ve continued to use a fair amount of Australian technical talent in your films.

A: Even on my first American picture, Witness, I did the post in Australia. It was more comfortable, and I preferred to keep my distance from Hollywood. I liked—and still like, I suppose—the feeling of being a foreigner to the United States, which is why it was important to me never to live there.

Q: Did you have any trepidation going into Witness?

A: Well, I had to settle in with a major star, Harrison Ford, and with the studio. I took some precautions that I think helped me feel comfortable that I’d have control of what I was doing. The meeting with Harrison went well, and then I had a meeting with Jeff Katzenberg and his associates at Paramount, and he offered me the picture. And then I set what was, in a way, a test for them. I said, 'Thank you, but first can I tell you the story?’ And Jeff said, ‘You want to pitch me a movie we’ve just offered you?’ ‘No, I just want to tell you the story so you’ll know what I’m going to do.’ This probably goes back to the performing side of my early career. So I gave them a little radio show, in a way: ‘We open with wheat fi elds blowing and through the fields come people in 19th-century costume, characters rolling down the road to a distant farmhouse…’ And so on. As I was telling the story I began to see gaps in it, so I went back to my hotel room and made notes about scenes that needed to be rewritten or added. I’ve done something like this on every movie since, either told someone the story or recorded it. It was useful for me, and at that meeting it also put me front and center, as the director should be.

Q: How do you decide what scripts you really want to do?

A: There’s some hook in it that’s drawn you in, a scene or a moment that resonated profoundly. That particular moment is generally impenetrable and mysterious, and it becomes critically important. I remember what it was in Fearless (1993). There are two men flying on a plane that’s in trouble, that’s going to go down, and one of them, the Jeff Bridges character, says to his partner, ‘I’m going to go forward and sit with that kid up there.’ And then the script says, ‘He moves down the aisle and sits beside the boy.’ It’s maybe an eighth of a page. That was the line that struck me—not what he says to his partner, not even his sitting down with the boy. Just his moving through the aircraft.

The moment’s gone now, because I actually thought it through intellectually and photographed it. When we came to schedule it, I told the AD I wanted half a day to shoot it, which I think was a bit of a surprise. It’s always hard to speak about what interested you in a piece, because it’s often something unknowable. It’s the nonintellectual, the unconscious that’s most important to me.

Q: Were you attracted to the technical challenge of shooting a crash from the point of view of people inside the plane?

A: Actually, there was more technical stuff initially, more crash action. But at some point I got in touch with some of the survivors of the incident on which the storywas based, and their descriptions of what it was like to be in this accident became the basis of how I shot it. I eliminated everything that wasn’t specifi c to their experience. Their experiences were more dreamlike, less real than you might have thought, so I took away all the sort of objective views.

Q: The movie was obviously kind of a tough sell, and it didn’t do very well at the box office.

A: For me, the only failure is if you don’t get hold of a piece, and you’re cursed when that happens, because when you have a quiet moment—often while flying, funnily enough—you start to remake it in your head. I carry a couple of those fi lms with me. But when you feel you got it, the box offi ce is only a matter of fate. When I made Fearless, I was coming off Green Card (1990), which was modestly successful, but it was a direction I didn’t want to continue in. Strangely, I felt uneasy about its success. I’d enjoyed doing it very much, but it was too comfortable. I wanted to deal with more diffi cult subject matter.

Q: Fearless certainly qualifies, and The Truman Show is pretty tough subject matter, too.

A:

The Truman Show was a wonderful script by Andrew Niccol, but originally it had a very different setting and tone. I worked for about 12 months adapting it to my sensibility. Originally it was much darker, it was set in New York, and the central character was more troubled. It was a completely successful piece of writing, but I thought it would fail on the screen, because I didn’t think it was believable that this grim show would have been so popular with a large, reality-addicted audience. So I made the setting sunnier and happier, kind of inspired by a long-running soap opera here in Australia, which is set not far from where I live, in fact. Beach, water, lovely little quaint houses, rather like a holiday resort. I’d done something similar with Dead Poets Society, changing not the setting but the time of the story. It had originally been set in the Kennedy era, and I moved it back into the Eisenhower era, which was when I was in school, at Scots College here in Sydney. That allowed me to draw on my own school experience, and to imagine more easily how I would have reacted to a teacher like the one Robin Williams plays. That’s the one fi lm of mine that’s really connected with the younger audience, with people in their teens and early 20s.

FAR FROM HOME: Weir being battle-tested on Gallipoli.

FAR FROM HOME: Weir being battle-tested on Gallipoli.

With Kelly McGillis and Harrison Ford on Witness.

With Kelly McGillis and Harrison Ford on Witness.

(Credits: (top) Kobal Collection; (bottom) Paramount (Pictures/Photofest)

Q: Was The Truman Show a difficult movie to cast?

A: I was in that very dangerous situation a director can sometimes be in, which is that there’s only one person you see playing a particular role. When I saw Jim Carrey in Ace Ventura, I thought, that’s the guy. And after I’d met him, I thought, my God, if he backs out it’ll all come apart. So I waited for him. I felt we were an ideal combination, because I’d worked in comedy and he had a background in stand-up. When we first met, we started improvising, making up scenes as we went along. On our second or third meeting, he took me into the bathroom and showed me how he’d do things in the mirror, inventing little sketches and scenes.

Q: As counterintuitive casting goes, though, that has to take second place to Linda Hunt as Billy Kwan in The Year of Living Dangerously.

A: That was a desperate and dangerous move. After a grim casting session in Los Angeles, where I’d been reading Mel Gibson’s part with all these actors trying to pull the sword out of the stone, the casting director held up a photograph, and I said, ‘That’s perfect,’ and he laughed and said, ‘It’s a woman.’ But I was desperate enough to meet her. She asked if I could rewrite the part as a woman, and I asked her if she thought she could do it as a man. She said, ‘As long as I know you believe in me.’ And in the event her performance was so strong it almost threw off the structure of the movie. When her character dies, the picture’s hanging by a thread.

Q: Do you do a lot of rehearsal with the actors?

A: Very little. When I do, it's only if the actor wants it. And in that case, I always prefer to improvise something that isn't in the picture, rather than 'let's do Scene 29.'

Q: Do you often do many takes?

A: No, I don’t. Partly, again, that’s the lowbudget filmmaking background. Film stock was so precious, time was so precious. And I fi nd that after a certain number of takes, when it gets into double digits, I lose concentration. After 15 or so—which is rare for me—I’ll call a halt. I’ll change something physical, the blocking or the handling of props. Often a camera angle change will help, will free you up to discover what’s wrong. And sometimes a scene just doesn’t want to be photographed. Maybe you have to break it into two scenes. Maybe you just have to come back to it another day.

Q: What about the social aspects of filmmaking, the camaraderie of cast and crew on the set? Do you worry much about that?

A: To a degree, but I think I need that less now than I did in the beginning. When you start off, you do need the kind of energy and support that comes from being a team. In the early days, having everybody excited was a kind of fuel that drove you on through. I think it may also have something to do with the Australian experience, because we came into the world of cinema so late.

Q: But you do still need a team.

A: Yes, and with any department head—the art director, the cinematographer, certainly the editors—the fi ne line is getting from them what you haven’t thought of yourself, and at the same time needing them to accept that you will make the decision in the end. You don’t want a rubber stamp at all. In casting these parts, as it were, you want somebody who can say, OK, let’s dig deeper into what your point of view is, see if we can go further with this. When that sort of collaboration emerges, it’s wonderful.

Q: You seem really interested in the, let’s say, less conscious aspects of the creative process. How do you get your unconscious going?

A: Sometimes I just write things out as a short story. I hate scripts, they’re such a horrible, bastard form of literature. But writing a scene out, in prose, can release things from the unconscious, which is the challenge in any creative endeavor. You want to get those dreamy kinds of thoughts, things that are alien to your own personality and worldview, which can be restricting and make your work repetitive. If you can let these unknown aspects of your person come through, you can make the work richer, and that’s what I think this kind of stream-of-consciousness writing does for me. It’s nothing like a script or a short story for publication. You can write down something that’s shocking to yourself, rather like a dream; you may release some sort of violence you didn’t know you had. I always say to students when I talk to them,write, write, write. You may not be very good, but it makes the mind agile, just as going to the gym does for the body.

Q: Is The Way Back finished now?

A: I saw an answer print last week.

Q: Do you have any idea how it’s going to be marketed?

A: That’s a field that if I thought I knew anything about five years ago, I know less today. It’s changing by the month, I would say. This is an uncomfortable era for nongenre films.

Q: What do you think has happened?

A: Because we’re going through this change right now it’s hard to get a broad view. Clearly there’s a change in the audience, a generation that’s grown up with video games and such, and who have different expectations from a film. And to cater to that audience, the distributors have changed their practices too rapidly. It’s not just a matter of cost. If a change has been too fast for the entire world public to have made, that creates a situation in which a lot of people are fi nding little to go and see, and they’re frustrated. The distributors presume that this middle audience is gone, but it’s not.

I hope it isn’t another seven years until your next movie. Do you have any ideas about what you might do next?

A: No, I really want to see how this film goes. I’m looking for information about where I might fit in this estranged fi lm world. To a degree that will affect what I do next, I think. I don’t want to change my approach to subject matter, I can’t simply move to the kinds of fi lms the studios are making now. Marvel Comics are not my interest, or my talent, or my experience. The studios know that, and I know that.