BY STEVE POND

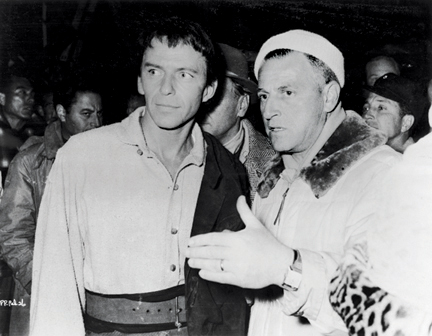

TAKING ORDERS: Sinatra won a best supporting Oscar for his performance

TAKING ORDERS: Sinatra won a best supporting Oscar for his performance

in Fred Zinnemann's From Here to Eternity, also with Montgomery

Clift (Photo Credit: Columbia/Photofest)

Would it be too obvious to say he did it his way?

Probably. But he did. And for the directors who made movies with Frank Sinatra, that fact required flexibility and ingenuity, preparation and confrontation, and a variety of techniques to deal with a legendary star who was not a trained actor, who had his own ideas about rehearsals and retakes and the many details with which every director must contend. In some ways it is the dilemma every director faces when working with high-profile stars with their own way of doing things, but in the case of Sinatra, it was in spades.

"Directing Frank Sinatra?" said Sidney J. Furie, who did just that in The Naked Runner in 1967. "What are you doing, writing a horror story?"

Then Furie laughed. "Actually, I'm going to surprise you: I liked the guy," he said. "He was a legend, and an icon, and a gentleman."

Sinatra acted in more than 50 movies in a 40-year screen career. Many of those films, to be honest, are not very good. He made throwaway musicals early in his career, when producers were trying to capitalize on his matinee idol status; he tossed off Rat Pack movies in the '60s, where breezing through the shoot and relying on the jokey camaraderie of the Chairman and his pals was the only thing on the agenda.

But in between, Sinatra also made some terrific films. When coaxed or confronted or inspired by top-notch material or a director who knew how to deal with him, he could turn into a wonderful actor. He won an Oscar for Fred Zinnemann's From Here to Eternity, might have deserved another for Otto Preminger's The Man with the Golden Arm, and turned in strong performances in everything from John Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate to Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen's On the Town.

"When Sinatra really wanted it, and when he respected the director, he worked hard," says Hawk Koch, whose father Howard was the head of Sinatra's production company in the early '60s. "If you look at The Manchurian Candidate, you see a guy who really took the time to act and did it well. "But most of the time, he didn't care," adds Koch. "And if he thought he could push the director around, that's what he tried to do."

No, Sinatra was not easy for directors. "He stayed up late every night, and in the morning he didn't show up for a while," says Dick McWhorter, who worked as unit production manager and line producer on two Sinatra films, Kings Go Forth (directed by Delmer Daves) and The List of Adrian Messenger (John Huston). "He never wanted to do more than two or three takes, and you had to schedule it so that when you called him, you were ready to go."

McWhorter pauses. "He had his own way of doing things."

As an actor, Frank Sinatra's M.O. remained the same throughout his career: he hated to rehearse, he hated retakes, he hated waiting. He earned the nickname One-Take Charlie. After being cast in 20th Century Fox's film version of Carousel (which contained one of his signature songs, "Soliloquy"), he refused to be in the movie because the studio wanted every scene shot twice—once in 35 mm, once in Cinemascope.

"He used to wait in his bungalow at Warner Bros. during the filming of Marriage on the Rocks," says Koch. "David Salven, a great first AD, would call the office and say, 'We're ready to shoot, Frank,' and Frank would say, 'Roll the camera when I walk in the front door, and when I hit my mark I'll say the lines.'"

"He'd come in, walk to his mark, say the lines, and then look straight into the camera and say, 'Cut, and print.' And then he'd turn around and walk out."

Similar stories abound. Sinatra refused to rehearse on one of his earliest films, It Happened in Brooklyn, to the point where MGM threatened legal action. He tore up script pages and said, "the scene's cut, see you tomorrow" when told that his tardiness didn't leave enough time to complete a scene. He tried to control the performances on Ocean's Eleven and veteran director Lewis Milestone was so exasperated he later said it was the "least favorite film that I ever made." And, in a legendary tirade, he threatened to urinate on Stanley Kramer if the director didn't finish a scene on The Pride and the Passion by 11:30 one night.

Everybody knew his reputation, and it scared some directors off. Billy Wilder was a friend of Sinatra's, but he wouldn't cast his pal. "I was afraid he would run after the first take," said Wilder. "'Bye-bye kid, that's it. I'm going, I've got to see a chick.' That would drive me crazy."

Otto Preminger, who directed The Man with the Golden Arm, summed it up in an interview with Evelyn Herbert:

"I was warned about Sinatra, and I had my misgivings," said Preminger. "I was told he was difficult. I could see that he was; he was a highly temperamental man, very touchy and very, very moody. He has a chip on his shoulder all the time…. He's full of contradictions…. If he thinks a person is untalented, he can be unbearable. And you always have a feeling he may be about to blow up."

And that's the assessment from a director who got along with the guy.

So how did directors deal with Ol' Blue Eyes?

By all accounts, the task required a few keys:

Be flexible. "You had to be creative," says Dick McWhorter. "I remember one Sunday night when we were shooting Kings Go Forth in the south of France, I got a call from [producer] Frank Ross. He asked what we were planning on doing in the morning, and I said we were shooting a café scene with Sinatra and Natalie Wood and Tony Curtis. And he said, 'Well, you won't have Frank in the morning. He's in New York with Ava Gardner.'

"So we put a double in Frank's clothes and shot what we could with the people we had, saving Frank's close-ups for later. And we did that kind of thing all the time. We had a double for driving, a double for walking…."

Virtually every day, says McWhorter, Daves and his crew prepared a couple of options: the scene they'd shoot if Sinatra showed up and was ready to work, and the alternative they could do if their leading man was AWOL or tardy.

"You can't just sit there with the crew waiting," he says. "So the key was to plan every day, but also have other things you could do."

When necessary, confront. Early in the production of The Naked Runner, which was produced by Sinatra's own company and directed by Sidney J. Furie, the star helicoptered to a location up the Thames from London. Fog slowed the pilot and turned what Sinatra had been told would be a 20-minute trip into something much longer. By the time he arrived on the set, Sinatra was fuming—and his mood wasn't helped, says Furie, when he saw that shooting was going to take place in a World War II Quonset hut.

"He said, 'Why did I have to come all that way for this?'" remembers Furie. "I said, 'There aren't many Quonset huts in London anymore,' and he said, 'Well, that's your problem.'"

But before Sinatra could follow through on his threat to leave, Furie went on the offensive. "I said, 'No, it's your problem. If you leave, you have to get back on that helicopter in the fog—but I just bought a new Jaguar, and I'm gonna drive my Jaguar back to London. And if the movie doesn't get made, this is your company, your deal.'"

Furie says he started to walk away, but heard a shout. "Stop!" Sinatra yelled. "You win, Furie! Let's get to work."

From that point on, Furie insists, Sinatra was easy to work with. "I never had any problems with him after that. If I wanted more than one take, all he said was, 'What should I do differently?' He responded like a musician would to hitting the notes."

Frank Sinatra with Delmer Daves and Natalie Wood on Kings Go Forth

Frank Sinatra with Delmer Daves and Natalie Wood on Kings Go Forth

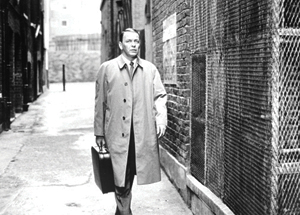

(top) Stanley Kramer on The Pride and the Passion (middle) and John

Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate. (Credit: MGM)

Prepare. A lot. This, says everyone who worked with Sinatra, was crucial. "Aaron Rosenberg, who produced The Detective, told me that the way they worked with Sinatra was to light six setups ahead," says director John Badham, who interviewed Rosenberg for his book I'll Be in My Trailer. "When he walked in the door at 10 o'clock in the morning, they'd put him right where he was supposed to be and shoot the first scene. Then they'd walk him to the next set, scrambling to light ahead of him. And by 2 or 3 they'd be done with him for the day."

Director Mark Robson did something similar on Von Ryan's Express in 1965, scheduling all Sinatra's scenes back-to-back to minimize his waiting. Gordon Douglas, whose Sinatra films included Robin and the 7 Hoods, Tony Rome and The Detective, pre-lit every scene and blocked it with Sinatra's double, so that he was ready to shoot as soon as his leading man appeared.

"That was always the key," says Koch. "When you called Frank to the set, you'd better be ready to roll camera."

Be patient, even if Frank isn't. Sinatra himself couldn't abide waiting, of course. But if a director would wait him out, sometimes the star would come around, his intransigence softening into something approaching cooperation.

In his autobiography, Take One, director Mervyn LeRoy remembered a day on the set of The Devil at 4 O'Clock on which he argued with Sinatra about a close-up that the star deemed unnecessary. A few minutes later with two hours remaining in the shooting schedule, Sinatra asked if he could go back to the hotel.

"I knew that it would be adding fuel to the fire if I insisted on him staying," wrote LeRoy, "so I said, 'Sure Frank, you can go.'" When LeRoy returned to the hotel that night, he found an apologetic note under his door from Sinatra, who proceeded to cook a spaghetti dinner for the director and the entire cast.

Negotiate. The political thriller The Manchurian Candidate was probably the last great movie Sinatra made, and one of the few times that the actor came in ready to listen to the director. "Sinatra really wanted to make that movie," says Koch, "and he had a lot of respect for John [Frankenheimer]."

Even so, Frankenheimer made sure that he and his actor were on the same page. "Sinatra had a terrible reputation in town," says Badham, who interviewed Frankenheimer about the experience for his book. "He was renowned for doing two takes, no more. As Frankenheimer said, Sinatra saw himself as a singer and performer who got things right from the start, and didn't want to wait around while he thought other people were making mistakes. And he was a terrible insomniac who didn't get to bed before 5 o'clock in the morning and didn't show up until the middle of the day."

Frankenheimer sat down with Sinatra and found, says Badham, "a more felicitous way of doing things. He said, 'Okay, we'll do French hours,' which is when you start at 10 o'clock in the morning, feed everybody as you go, and then go home early. And that seemed to work for Sinatra."

To limit the number of takes, Frankenheimer promised to "rehearse the bejeezus out of it, so that when you come in, there won't be people with measuring tapes getting focus points." And he asked Sinatra to rehearse as well. "If you do that," Frankenheimer told Sinatra, "we can pretty well guarantee that we won't screw it up technically." Sinatra agreed.

"I think a director owes it to himself and to an actor to try and have as many meetings and as many encounters as possible before you start filming," Frankenheimer told Badham, "so that there is some kind of relationship when you walk on the set.

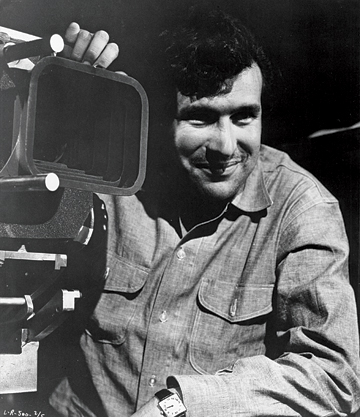

MIND GAMES: As a first time director, Bud Yorkin (top) appealed to

MIND GAMES: As a first time director, Bud Yorkin (top) appealed to

Sinatra's gallantry on Come Blow Your Horn and it worked. Sidney

J. Furie (bottom) says he called Sinatra's bluff on The Naked Runner.

(Photo Credits: BFI; AMPAS)

Appeal to his gallantry

. This was the approach taken by Bud Yorkin, who made his directorial debut on Come Blow Your Horn in 1963. It was also the first film for Tony Bill, then an actor, who says Sinatra was always "extremely patient and generous when I was around."

It was clear, says Bill, that the star didn't like to do many takes—but it was also clear that he was on his best behavior with the young actor. "I think Bud used me as an excuse a few times," says Bill with a laugh. "He'd tell Sinatra, 'I need another one for the kid,' and Frank would say okay."

Bill went on to act in two more Sinatra movies: the comedy Marriage on the Rocks and the World War II film None but the Brave, which Sinatra himself directed. "An impatient director is a bit of an oxymoron," Bill says, "but he brought that quality to directing as well."

If all else fails, go on without him. Sometimes, despite the best-laid plans, there was nothing else to do but let Sinatra walk away. Stanley Kramer encountered this on The Pride and the Passion, when he recalled his leading man being "deeply involved in a serious personal dilemma" of an unspecified nature. At one point, the director wrote in his autobiography, Sinatra came to him with a simple statement: "Hot or cold, I'm leaving Thursday. If you can't live with that, you should get a lawyer and sue me. I wouldn't blame you."

For the rest of the shoot in Italy, Kramer used Sinatra's double and shot over his shoulder in scenes with Cary Grant. "Grant did this so convincingly that few, if any, would realize it wasn't real," wrote Kramer.

Then, back in the U.S., the crew built new sets, and Kramer filmed the final scenes with an apologetic Sinatra.

So was it worth it? Some directors certainly thought so. Kramer called him "an actor with a far greater range than most people noticed." Fred Zinnemann described him as "wonderful to work with 90 percent of the time." Preminger called him "an extraordinary man."

"He was Sinatra," says Sidney J. Furie. "We were all star-struck."

And so a string of directors put up with it all, and some of them didn't even regret it afterwards. And all of them, to be sure, left with good stories.

So here's one final story, a tale from the set of Come Blow Your Horn. It took place one day after neophyte director Bud Yorkin had offended his leading man by making some kind of suggestion to which Sinatra took umbrage.

In the morning, Sinatra requested a meeting. Yorkin made his way to the star's dressing room—where, according to Michael Freedland's biography of Sinatra, All the Way, the conversation went something like this:

"Did you ever hear that I was difficult to work with?" asked Sinatra.

"Yeah, I've heard of it," said Yorkin.

"Did you hear that I don't like to do a lot of takes? Did you hear that?"

"Yeah, I've heard that.""And you've heard that come 5 o'clock, that's cocktail hour—and I don't like to work past that. Have you heard that?"

"Yeah," admitted Yorkin. "As a matter of fact, I've heard that, too."

"Well, if you've heard all that, why didn't you get Gordon MacRae to play the part? He's a sweet guy. He'll cause you no problems."

Whereupon both Yorkin and Sinatra burst out laughing, and the man who did it his way grinned at the young director.

"C'mon pal," Sinatra said, cooperative rather than combative. "Let's get this thing over with."