BY GARY GIDDINS

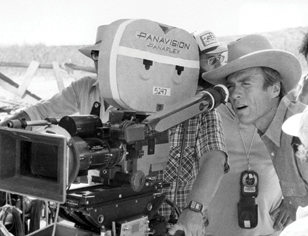

Honkytonk Man. (Credit: Warner Bros./Photofest)

Honkytonk Man. (Credit: Warner Bros./Photofest)

As he approaches 80, Clint Eastwood is a living testament to good genetics, relentless work, and a devotion to cinema bordering on religious avowal. The ultimate insider, who bestrides the Warner Bros. lot as perhaps no other director-star has, he remains a paradox—alternating (much as Graham Greene once insisted on labeling his novels as either "serious" or "entertainments") box-office bonanzas and defiantly personal projects. Though, at this point, one might argue, that they are largely indistinguishable from each other: Eastwood is always Eastwood.

He is a genre champ who questions the verities of genre; the Man with No Name who celebrates the necessity of nontraditional families; the commercially savvy action figure who relishes artists functioning in the absence of commercial dictates; the killing machine who comes to abhor violence; and, most surprisingly, the youthful vigilante-agnostic who takes the law into his own hands, only to accept, with maturity, the implacable burden of mortal sin.

In celebration of his milestone birthday, the studio where he has spent much of that time has issued a handsome DVD omnibus: Clint Eastwood: 35 Films 35 Years at Warner Bros., consisting of 34 Eastwood films made between 1968 and 2008—19 directed and starring him, 4 just directed by him, 11 just starring him. This release is something of a corporate celebration, and not an occasion for refurbished prints. These discs have been long available; here they are double-sided and wedged into cardboard slits that defy you not to leave fingerprints. The 35th film is a short documentary, The Eastwood Factor, directed by Richard Schickel, which is an excerpt from a feature documentary of the same name in which Eastwood gives his Boswell a walking tour through the Warner lot and his filmmaking past. (To mark the occasion, Schickel, who wrote the standard Eastwood biography in 1997, has also put together a smart and sumptuous photographic assessment of Eastwood's entire career, Clint: A Retrospective.)

The key Eastwood films made outside Warner—Play Misty for Me, High Plains Drifter, Escape from Alcatraz, In the Line of Fire, Changeling, Flags of Our Fathers—are available from Paramount, Universal, and Sony. Poring through them as well as the Warner Bros. box confirms the suspicion that while Eastwood is justly renowned as a director whose learning curve ever rises, he has always been his own man.

Part of his singularity surely proceeds from his generational displacement. He did odd jobs before making his way into the declining studio system, accumulating nearly a dozen small or bit parts before landing a leading role in 1959 in the television series Rawhide, which ran until 1966. He had to go abroad to find international recognition as the nameless cheroot-smoking gunman ('Blondie,' as one character calls him) in a trilogy of Sergio Leone Westerns. He knew his strengths and weaknesses ("a good man knows his limitations," is a Dirty Harry mantra), and chose to beef up his close-ups and winnow down his dialogue. He was nearing 40 when he came home to prod a Hollywood career, and past that when he achieved a breakthrough in 1971 with Dirty Harry.

If you saw Dirty Harry first-run, you probably remember the experience: audiences were exhilarated and vocal, laughing and wincing at unexpected lines and plot turns, recognizing that here was a newfangled version of an old-fashioned staple: a good man who shoots his way past moral ambiguity. In later years, Eastwood would fine-tune, parody, and ponder that character, but he would never abandon it, not even when he shoots Gene Hackman point-blank in Unforgiven, or sacrifices his life to salvage some meaning from it in Gran Torino. The Hollywood cinema of 1971 was beset with corruption and despair in the West (McCabe & Mrs. Miller), the city (The French Connection), and the heartland (The Last Picture Show). If Dirty Harry is dated now by its wink-wink ethnic slurs and an outlandish stop-the-action speech in which Harry taunts a perp with what sounds like an ad for the 44 magnum ("it will blow your head clean off"), it remains an enthralling portrait of an era (even Harry gives way to despair, tossing his badge as Gary Cooper had done in High Noon). To a degree, Eastwood's subsequent career as a director has been a coming to grips with Dirty Harry: How do we define heroism, justice, individualism, community?

Dirty Harry was the fourth of five Eastwood films directed by his mentor Don Siegel, who had turned out an impressive body of 1950s B-features, drenched in violence and paranoia (Private Hell 36, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Lineup). While working on Dirty Harry, Eastwood directed his first film, Play Misty for Me, in 1971, a fast, visually surprising thriller (especially in the sequences shot at the Monterey Jazz Festival), with a stunning performance by Jessica Walter as an insanely possessive suitor. More impressive were his pictorially ambitious ghost Westerns, High Plains Drifter (1973), followed in 1985 by his dark, mud-splattered Shane variation, Pale Rider. Shot at night with elliptical flashbacks, an eccentric cast, a dreamlike tempo, and swatches of brilliant color, these two Westerns imply that justice must come from the divine or it won't come at all.

Between them, in 1976, he directed and starred in his first undoubted masterpiece, The Outlaw Josey Wales, from a script by Philip Kaufman, a post-Civil War picaresque story in which relentless killing and overwhelming longing for vengeance is balanced by a kind of Chaucerian pilgrimage as the determinedly isolated Wales reluctantly leads a community of misfits, exiles, and malcontents. Among them is Chief Dan George as an unforgettable, oracular Indian who tries to measure up, with mixed success, to tribal lore. By now, Eastwood was given to signature bits of characterizations—a one-liner like "make my day," or, in this instance, a propensity for spitting tobacco juice. Irreverent comedy is almost always part of the Eastwood mix, though many critics could not see it.

This became especially apparent in his next director-actor vehicle, The Gauntlet (1977), dismissed as a sop to box-office demands even by some of his admirers. This is a film that needs to be seen for what it is: one of the funnier American comedies of its time, and with one of the best musical scores—a jazz holler arranged by Jerry Fielding, featuring saxophonist Art Pepper and trumpeter Jon Faddis. Admittedly, the movie is built on a single joke: Eastwood's cop is an honest idiot, who would be dead a dozen times but for the ministrations of the reluctant witness in his protection—an educated prostitute (Sondra Locke), who obliges him to confront the fact that the police are out to kill them both. Everything is sublimely overdone: bullets demolish buildings, cars, and an improbable bus. It's a fantasy of excess, girded by two of Eastwood's abiding themes—doing your duty and getting the hell out of there.

Eastwood continued to alternate between pop projects (the decline of Dirty Harry and two charming films with an orangutan) and those that undermined the basic fabric of the heroes he formerly celebrated. The "hero" cop he plays in Tightrope (1984) has much in common with the sexual deviant he pursues, and the country singer he plays in Honkytonk Man is bent on self-destruction.

Two films, four years apart, utterly changed his stature as a director. In 1988, he took on a Joel Oliansky script about Charlie Parker, Bird, which had been floating around for years. With Forest Whitaker as Parker and Diane Venora as his wife, Eastwood defied the expectations of his audience, losing money to make a classic that gets better with the years. Rebuilding New York's fabled 52nd Street on the Warner lot, Eastwood made the first American film to take the point of view of a black genius, to take on black urban culture, racism, miscegenation, drugs, madness, as well as the solace and limits of art. And he made it without expository dialogue to explain Parker or his music.

He followed it with another superb, woefully undervalued dissection of a self-destructive genius, John Huston, in White Hunter Black Heart, based on the shenanigans that preceded Huston's making of The African Queen. Eastwood played the lead role with a cheerfully accurate version of Huston's speech patterns. (Daniel Day-Lewis did the same in deadly earnest in There Will Be Blood.) Beautifully filmed by Jack N. Green (shooting, for once, as much daylight as night), this ultimately devastating look at an artist who can't face his own talent proved that Eastwood could pilot an intricate script, balancing farce and tragedy, while sustaining a brisk storytelling detachment that echoes Huston's own directorial style. Yet the material proved too inside for a general audience.

That was not the case with Unforgiven, the 1992 Western epic that questioned all the generic givens of the idiom, while employing them with pitch-perfect accuracy. Functioning on at least three levels, David Webb Peoples' script weaves stories of revenge, corruption, and the fantasy world of public relations (also a target in the final and slightest Harry film, The Dead Pool). It was impossible for the audience to ignore Eastwood as a director of stylish originality, and as an actor far deeper than the lanky Hollywood pretty boy who quipped, smirked, and scowled his way through his earliest films.

Although some are lightweight and may ultimately fail (the sudden comic turn by Judy Davis near the climax of Absolute Power took the power down several notches), every film Eastwood has made since Unforgiven is distinct and worth seeing—or seeing again. He tells stories no one else tells, at least not in movies: the political betrayal of the Iwo Jima troops in Flags of Our Fathers; the fears and doubts of the grunts who made up the universally demonized Japanese army in Letters from Iwo Jima; the bedlam, incarceration and corruption that threatened women during the Great Depression in Changeling; the connection between sports and racial identity in Invictus.

Yet perhaps the two greatest of his late-period films are the Catholic diptych, Million Dollar Baby (2004) and Gran Torino (2008). The former exemplifies Eastwood's ability to define a time and a place, while crafting a performance in tandem with inspired actors (Hilary Swank, Morgan Freeman). But the heart of the film is the all-consuming father-daughter love that rises from circumstance and mutual need. In many of Eastwood's films, women, particularly daughters, are killed or butchered—in Josey Wales, The Enforcer, Tightrope, Unforgiven, Mystic River—but never more poignantly than in Million Dollar Baby, where love is so powerful that Frankie Dunn (Eastwood), a fervent Catholic, offers a mercy killing that will doom him to a purgatory in which he fully believes. Similarly, his crusty old racist Walt Kowalski in the serenely made Gran Torino—a picture with a paint-by-numbers inevitability that nonetheless is utterly compelling—orchestrates his own suicide to bring order to a community he has finally learned to love.

One advantage of directing himself is that Eastwood can give himself good roles at an age when most actors are scrounging. How many Hollywood stars have takenon as demanding and memorable a part as Walt Kowalski at 78? Eastwood has not only outlasted the generation to which he was born, but the one that followed. Of the major film stars born several years later, a small handful (Robert Redford, Warren Beatty, Burt Reynolds, Jack Nicholson) turned to directing, sometimes with great success, but only Woody Allen matches Eastwood in the constancy and dedication to both crafts. The Man with No Name has become one of the few directors in the world whose every film is a worldwide event, whether he appears in it or not.