(Da Capo Press, 368 pages, $15.95)

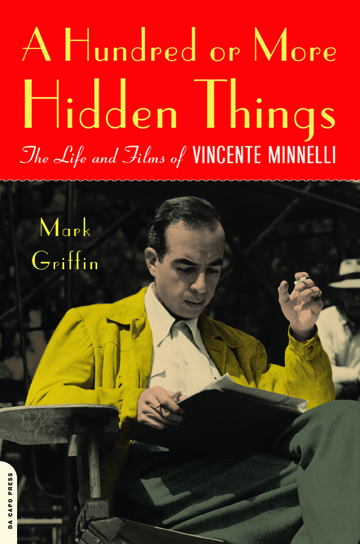

By Mark Griffin

Vincente Minnelli was a contradictory man, says Mark Griffin in his enlightening new biography of the director. For starters, his real first name was Lester, though he discarded that moniker just as he kicked the dust of Delaware, Ohio, from his heels before reinventing himself in Chicago, New York and Hollywood. He spent his childhood touring with his parents’ tent theater troupe, became Marshall Field’s top window dresser, then king of the Broadway revue, and, finally, the epoch-making director of musicals and cinemascope melodramas in the 1940s and ’50s. As Minnelli himself later put it, he “brought the sleek lines of modernism into the theater,” then transfused them wholesale into the Freed unit at MGM, giving us

Meet Me in St. Louis, An American in Paris, The Bandwagon, Gigi and many others.

Minnelli was a gay or bi-sexual man who married four times. Often awkward and ill at ease in his personal dealings, particularly with non-creative types, his neuroses and tics could be disconcerting if misunderstood. But he was also friends with almost every musical genius of his day, from Gershwin to Lerner to Comden and Green. In his own realm—mostly at talent-stuffed MGM—he commanded total respect for his innovative sense of design, costumes, choreography and camerawork (if Billy Wilder was a writer-director, Minnelli was primarily a designer-director), and for the gossamer universe in which his pioneering musicals unfolded.

Noting these contradictions, and having discovered through multiple interviews that Minnelli kept his gay and straight worlds effectively compartmentalized, Griffin chooses to approach the director through his work, in hopes of discerning biographical or confessional impulses. At the same time, his method expands our understanding of the movies. Griffin concludes that both Minnelli’s buoyant musicals and vivid melodramas operate on clashing principles of expressionism and utopianism, and often feature characters—writers, painters, dancers, musicians—for whom, as for Minnelli, artistic creation is a refuge from a rough world.

Griffin, a talented and sympathetic writer, colors and shades our hitherto murky understanding of the man who made those movies. Given this interpretation, it’s easy to see why the gifted and tormented Minnelli completely identified with the similarly gifted and tormented Vincent van Gogh in

Lust for Life.

Review written by John Patterson.