BY STEVE POND

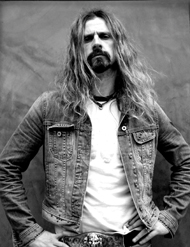

EARLY ATTRACTION: Rob Zombie has used

EARLY ATTRACTION: Rob Zombie has used

Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange for

videos,

Halloween costumes and stage shows.To borrow a phrase from one of his favorite films, Rob Zombie always liked to "viddy" movies.

He may have grown up to be a rock star with his heavy metal band White Zombie before branching out to direct the likes of The Devil's Rejects and his two Halloween reimaginings, but as a child, Robert Bartleh Cummings was obsessed with, he says, "everything from the Marx Brothers to Godzilla." His bible was a worn copy of the book Midnight Movies, and his quest was to see everything in its pages. One hotly anticipated film, which the high schooler finally saw when it screened at a local college, was Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange.

"I remember looking at the pictures endlessly in Midnight Movies, and I also had the Clockwork Orange soundtrack," Zombie says. "I felt like, these are really cool pictures, but how could they add up to a cohesive movie? And when I did see it, everything about it was mind-blowing. It had the most extreme character I'd ever seen, and the film itself was so rich but so twisted. No matter how many movies you've seen, there's no other movie like it."

Zombie cues up the film, a 1972 Oscar nominee for best picture, and settles into a chair in the dramatic screening room of his Los Angeles home. He's surrounded by classic horror movie posters, oil paintings of celebrated screen monsters and a huge case of props from his own films. The room speaks of an artist whose career, both in music and in film, has been centered on the horror genre—but the dreadlocked guy in shorts and a T-shirt says his tastes and ambitions go far beyond that. "I love dark, weird material," he says. "This is dark and weird, but it's not a horror movie."

Based on the dystopian novel by British author Anthony Burgess, Kubrick's controversial film begins with the portentous chords of Wendy (then Walter) Carlos' main theme, a synthesizer-based take on Henry Purcell's funeral music, and with a bright red screen held for 25 seconds before the stark white titles appear. "Even this opening title sequence is amazing," Zombie says, delighted to be seeing the film again. "Nobody would do this now, just leave the screen red for so long."

The action begins with a typical Kubrick flourish—a long tracking shot that starts tight on the face of Malcolm McDowell's psychopathic teenager Alex, then backs up to slowly reveal the Korova Milk Bar, a futuristic nightspot where Alex and his three "droogs" drink drugged milk to prepare them for a night of random violence.

Malcom McDowell's Alex gets ready for a brutal night out. (Photo: courtesy of Warner Bros.)

Malcom McDowell's Alex gets ready for a brutal night out. (Photo: courtesy of Warner Bros.)

"I've used Clockwork for videos, Halloween costumes, stage shows, songs," Zombie says. "We recreated this scene for a video ["Never Gonna Stop (The Red Red Kroovy)"]. We spent forever rebuilding this whole bar, and we did this whole long tracking shot. And then the lawyers at Geffen Records said we did it too identical, and they got nervous that we were going to get sued by the Kubrick estate. They said, 'You guys made it too exact—go back and make it different.'"

When Alex and his gang leave the Korova, we get a quick introduction to their brutal m.o. when they assault an aging homeless man, not for money but for the thrill of what Alex calls "the old ultra-violence." "I went back and found a Roger Ebert review, and he hated this movie," says Zombie, shaking his head. "He seemed to have a real problem with Alex, this lead character with seemingly no redeeming qualities. But to me, that's what I loved about it. I love having the bad characters be the lead characters, because they're so much more interesting. I have this theory that it's all about cool: If characters are cool, people will get behind them and have sympathy for them. It doesn't matter if it's Alex or Dirty Harry."

One of the major set pieces early in the film comes when the droogs encounter a rival gang about to rape a young woman. The subsequent brawl is choreographed to the strains of Rossini's The Thieving Magpie overture. Zombie relishes the disconnect that comes from setting unsavory action to classical music. "I love taking really nice music and perverting it in movies," says Zombie, who's used cheery pop songs like the Bellamy Brothers' "Let Your Love Flow" in brutal films like The Devil's Rejects. "I think this may have been the first super-perversion of music I ever saw in a movie, and now I can't hear Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, or the William Tell Overture, or the other music from Clockwork, any other way."

"I had lunch with Malcolm," says Zombie, who cast McDowell in Halloween II, "and he said they rehearsed this for five days, and it was just five days of Stanley sitting there stroking his beard, totally confused about what to do. Every day a truck would arrive with new furniture and they would redo the set, and still not shoot anything. And after the fifth day Stanley had an inspiration and said to Malcolm, 'Do you know how to dance?' Of course, Malcolm said yes, and I guess 'Singin' in the Rain' was the only song he knew the words to, so they used it. It's funny how it's one of the most memorable scenes in this meticulously constructed film, but it uses 'Singin' in the Rain' just because that's the only song Malcolm knew."

WARM-UP ACT: After a stop at the Korova Milk Bar for some drugged refreshments,

WARM-UP ACT: After a stop at the Korova Milk Bar for some drugged refreshments,

Alex and his droogs attack an elderly homless man just for kicks to start their night off

with a bang. Zombie loves the fact that the bad guy is the hero. (Credit: Warner Bros.)

Watching the scene—which helped earn the movie an X rating—Zombie shakes his head. "To see a movie that's so beautiful, and yet so extreme on sex and violence, was something I'd never experienced before," he says. "And even today, this is pretty extreme." He shrugs. "I guess that was my problem with [Kubrick's final film in 1999] Eyes Wide Shut—for a movie that was supposed to be so sexually shocking and explicit, it felt so tame. It felt like Kubrick had fallen out of touch with the world. Whereas this still seems crazy."

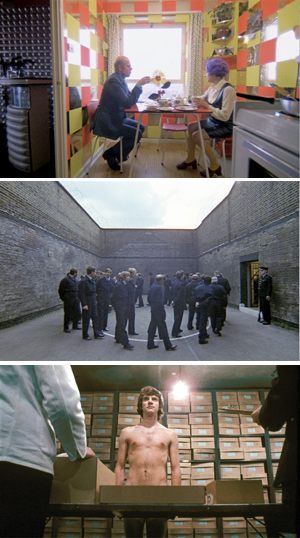

When Alex arrives home after his night on the town, Zombie grins at the décor of his parents' flat: orange and green checkered wallpaper, red walls and blue ceilings, an oddly placed Farfisa keyboard. "I love this production design, it's so cool. It's that weird, tacky, late '60s version of what the future would be."

Zombie, who has been slouching in his chair, suddenly sits up as the hooky-playing Alex is surprised at home by a school official. "That guy always bothered me, he's so creepy," he says of Mr. Deltoid, who delivers a lecture, then a fist to the groin of the underwear-clad teenager. What Zombie points out is the way the lengthy scene between Alex and Deltoid unfolds almost entirely in one static two-shot, the camera positioned in the doorway of the room where the characters are sitting. "The pacing is so strange, the way they just hang on these shots for so long," he says. "There's not a lot of coverage, and very rarely are there any close-ups. This entire scene, except for the shot at the door, is that one shot. Which I can only imagine was brutal for the actors, all the long takes."

When a subsequent scene finds Alex facing off against a feisty, yoga-practicing woman at a health spa, Zombie notes the stark white light that illuminates the fight. "One of the reasons it's so disturbing is because the lighting is so bright in all these violent scenes," he says. "Apparently Stanley would check the lighting by taking Polaroids, and some days that was all he would do all day long. Malcolm told me Stanley took 70,000 Polaroids during the course of the movie."

HARD TIMES: (top to bottom) Alex's parents in their flat with orange and

HARD TIMES: (top to bottom) Alex's parents in their flat with orange and

green checkered wallpaper; Alex checks into prison; Kubrick used

a wide-angle lens in the prison yard to exaggerate the space.

(Credits: (top to bottom) Warner Bros; Photofest; Warner Bros)

The health spa foray lands Alex in prison for murder, launching the film's second act with a painstakingly detailed scene in which a cartoonishly officious prison guard checks in the hoodlum, takes all his clothes and belongings, and issues a new identity: "6-double-5-3-2-1." "This scene just goes on forever, but it's totally interesting," says Zombie. "I'm sure that's why he cast such bizarre secondary characters, because the scene would've become so boring if that guy wasn't so odd. Everything about it is just awkward and weird." He pauses, and notices the bright lights that ring the cavernous prison room. "I wonder if this whole scene was just lit by those practicals," he muses. "It looks like it."

Zombie points at the screen when the scene shifts to an outdoor courtyard in which a huge wall seems to loom over the rows of inmates. "The constant use of the wide-angle lens really helps the scope of this movie," he observes. "It really feels like a big movie. That's always a good trick—using wide lenses, and placing them close to a wall to exaggerate the space. You see that a lot in this movie, where the walls always seem so big and looming. He did that in The Shining, too, and I used it in the sanitarium scenes in Halloween II."

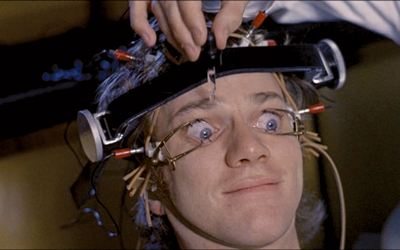

The prison section of the film ends with one of its most iconic sequences, in which Alex, undergoing the experimental "Ludovico technique," designed to produce physical revulsion at the very thought of violence, is strapped into a theater seat and forced to watch violent films with his eyelids held open by metal clamps. As he watches the films, a technician sits next to Alex administering eye drops at regular intervals. Zombie watches, and grimaces. "I guess the guy who clamped on those things and was supposed to put the eye drops in was an actual doctor," he explains. "And he got caught up in Malcolm's performance and kept forgetting to put the eye drops in."

Alex is released from prison a changed man and he finds that his parents have taken in a boarder and no longer have room for him; the homeless man he'd beaten earlier attacks him; and two of his old droogs, now cops, beat him close to death. Dazed and bleeding, Alex unknowingly stumbles to the same remote home where he'd assaulted the writer and raped his wife.

Zombie cracks up. "This is like something out of Young Frankenstein," he says, almost incredulously, as he watches a lengthy, awkward scene in which Alex dines with the writer, who has recognized him and is trying to stifle his almost catatonic rage.

The performances are so strange and over-the-top that sometimes they're on the verge of being a little too much. But Kubrick gives them so much room to breathe that they make sense. None of these people are realistic, but within the context of the film, they're hyper-real."

To cure him of his violent tendencies, Alex is given the "Ludovico technique."

To cure him of his violent tendencies, Alex is given the "Ludovico technique."

(Credit: Warner Bros)

It's an issue that Zombie himself has faced in movies like House of 1000 Corpses, where the characters can be so exaggerated they seem ridiculous. "I struggle with it sometimes, especially when you have extreme actors," he says. "Their actual personalities are so larger-than-life that what you're putting on film sometimes is more subdued than what they are in person. Then somebody will go, 'Oh my god, they're so over the top.' And I don't see it that way, because I've seen what they're really like." He laughs at the thought. "From Malcolm to Karen Black [who appeared in Zombie's House of 1000 Corpses], some people are just unique."

Seeking revenge, the writer plays Beethoven, which drives Alex to attempt suicide by jumping out a window, but he doesn't die. Instead, he awakens in a hospital with vague memories of doctors tinkering inside his head while he was unconscious.

Now Zombie gets excited in anticipation of one of his favorite scenes. A government minister, anxious to use Alex's recovery to make political points, pays him a visit at mealtime. While feeding the patient (who can't feed himself because his arms are in casts), he says he hopes Alex will consider the government a friend. "I think this is one of the best scenes in the whole movie," says Zombie. "It's so funny, because Alex is acting like such a shit here. Every time the movie gets too serious, there's something absolutely ridiculous, like him opening his mouth to be fed. And I know that was something Malcolm improvised."

Zombie continues. "Technically, it doesn't seem like anything in this movie was ever spontaneous—everything is so perfectly composed, and every dolly shot is so perfect. But if you really look at it, a lot of the best things in the movie actually were spontaneous."

At the end, the Ninth Symphony is blasting and Alex is having visions of wild sex in front of an applauding audience; his final line is, "I was cured all right." "It seems so joyous that he's back," says Zombie. "He's back to his old horrible self—and because he's so charismatic, we are happy about it. And then Kubrick cuts to this strange image of Victorian people cheering. That's why I love it, because so many of the images are iconic, but also just insane."

Considering the impact Clockwork has had on his own work, Zombie says, "stylistically, this movie doesn't really come into play with too much of what I do. Most of Halloween II was shot handheld and real loose, but when we got to scenes in the sanitarium we referenced a bunch of Kubrick and did big, long, blocked-off, composed frames. And at the end, we had this one long tracking shot, which was actually a Steadicam on a dolly. The movie ends on the lead actress' face. She's totally mad, and it's like she's happy to be crazy again. It's almost like Alex: 'I was cured all right.' It's a full-on Clockwork ending, and when we shot it we all laughed."