BY LYNDON STAMBLER

SOMETHING SLIMY: When Crude director Joe Berlinger, interviewing Trudie Styler,

SOMETHING SLIMY: When Crude director Joe Berlinger, interviewing Trudie Styler,

first saw the abandoned oil pits in the Amazon, he "felt the universe tapping me

on the shoulder, enlisting me to make this film." (Credit: Sebastian Posingi)

"If you want the least amount of money, the hardest problems to solve, the least glamorous part of the movie business, then documentaries are for you," says Davis Guggenheim, Academy Award-winning director of An Inconvenient Truth.

And if you want to make things even more difficult, you'll become a social activist documentarian. They film in 120-degree heat, get shot at by thugs, get sued by corporations, and generally stir up controversy. They gather hundreds of hours of footage in the field and somehow manage to craft dramatic stories in the editing room. Such is the lot of documentary filmmakers who are addressing contemporary issues in a variety of styles.

Indeed, documentaries with an agenda seem to have filled a breach left by traditional news outlets reluctant to take a stand. Audiences seek out films like Michael Moore's Capitalism: A Love Story, to help figure out the economic crisis, or Errol Morris' The Fog of War, about former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and the Vietnam War, to help fill in the gaps. "If it's messy or if it's going to offend an advertiser, those stories don't get told [on TV]," says veteran documentary director Joe Berlinger. "Independent documentaries have become a replacement for what hard-hitting news used to do."

Take, for instance, Berlinger's Crude, an exposé about the contamination of the Ecuadorian rainforest by a callous oil company. But when Berlinger first heard about a lawsuit filed by the indigenous Cofán people against Chevron, he wasn't sure if it would make for a compelling documentary. Three years later, the story, as well as the film, have become front page news.

The Cofán claimed that Texaco (now part of Chevron) had polluted their Amazon homeland beginning in the 1960s, tainting the water and causing cancer rates to soar. But Berlinger, who likes to shoot cinéma vérité style as reality unfolds, didn't know if he could find a character to drive the story.

Then the plaintiff's lawyer, Steven Donziger, took him to the Amazon. Berlinger became nauseous after visiting abandoned oil pits. He canoed to a Cofán village where people ate canned tuna because they couldn't eat fish from the river. "I felt the universe tapping me on the shoulder, enlisting me to make this film."

Determined to make a balanced yet engaging film, Berlinger used $100,000 of his own money to make a trailer and attracted partial funding from Netflix and Entendre films. Without a script, he spent three years trudging around the sweltering Amazon, his feet itching from chigger bites, two miles from the Colombian-rebel strongholds. "I'm amazed at the access we got," he says. "We stuck our camera everywhere. I used small format [Sony Z1U] HDV cameras. They're small, portable and I was able to be completely autonomous with a one or two-person crew."

Ironically, Berlinger thinks that filming people whom he couldn't understand—they spoke only A'ingae (the Cofán's language) or Spanish—honed his skills as a director. "I became more keenly aware of body language and how to anticipate where to move the camera and how to read real-life scenes," he says.

Berlinger unsparingly portrays Donziger as both an activist and for-profit lawyer, showing him coach a Cofán before he addresses a shareholder meeting. Trudie Styler, Sting's wife, became involved in the cause after reading a feature in Vanity Fair, and Donziger instructs her to mention Texaco more. "A lot of advocacy filmmakers would have left those scenes on the cutting room floor," says Berlinger.

GRAZING: Robert Kenner's Food, Inc. includes a visit to Polyface Farm in Virginia

GRAZING: Robert Kenner's Food, Inc. includes a visit to Polyface Farm in Virginia

and a soybean field being harvested (top). His goal was to leave the

audience "delightfully distressed." (Credits: Magnolia Pictures)

When shooting was over, Berlinger came home with 600 hours of footage and began constructing his story. "I don't approach structure before I take all the material and cut every scene," he says of his method of working. "It drives the editors crazy."

In order to make sure the film was fair, he kept a tote board; if he deleted an argument favoring Chevron, he removed one favoring the Cofáns. "The film is literally balanced and yet nobody walks away thinking Chevron are the good guys."

Finally, he chiseled the footage into a 104-minute film. "There were iterations that felt like this is not going to fly as theatrical 'entertainment,'" he confesses. "Obviously you have to use that word loosely when you're dealing with people dying of cancer in the Amazon. Basically, you have to be a storyteller."

As a committed filmmaker, Berlinger hopes his evenhanded approach will reach beyond the converted. "My point of view is in the film, but it's buried beneath the surface and open to interpretation. That's the hallmark of a cinéma vérité filmmaker. We don't use narration; we allow a multiplicity of viewpoints."

Barbara Kopple, a two-time Oscar winner who was nearly killed by machine gun fire while filming Harlan County USA, takes a similar approach. She starts a project without a fixed idea. "It's real life," she says. "You know basically what you're going to do, but that doesn't mean that's what's going to happen. You put on your sneakers and run with whatever's going on. That's what makes it exciting and alive."

Other activist documentarians like Guggenheim set out with a specific point of view. "We weren't worrying about sharing the microphone," he says of making An Inconvenient Truth. "You need some sort of organizing principle." Guggenheim, who more recently directed It Might Get Loud, about three legendary rock guitarists, knew where he wanted to go. "Here's your tone. Here's who you're following. If you don't have that, you'll shoot thousands of hours and end up with no movie."

Along the way, Guggenheim humanized Al Gore's slide show by blending charts, graphs and CO2 levels with tales from Gore's life. "Here's a guy who woke up in the '70s and learned this terrible truth about our environment," explains the director. "He spent 40 years trying to tell people about it and no one would listen. His personal stories are a third of the movie. Some people don't remember the personal stories but I guarantee you when you watch the movie, that's the thing that keeps you connected. People don't go to a movie to stimulate their brains. They go to be emotionally hooked."

BATTLE SCARS: Barbara Kopple was nearly killed by machine

BATTLE SCARS: Barbara Kopple was nearly killed by machine

gun fire while filming her Academy Award-winning Harlan

County USA in 1976 about the violent battle over

unionization between coal miners and their

employer. (Credits: Cabin Creek Films)

To capture the variety of material he was juggling, Guggenheim used 10 different formats, including Super 16 mm, 8 mm, HD, and stills. "We shoot everything in any way we can. It's the contrast between those different looks that makes documentaries so thrilling."

But when investigating social issues, directors often find that things don't go according to plan. In his film Food, Inc., a look at the food production industry, director Robert Kenner had hoped to include multiple voices. For his previous film, Two Days in October, about an ambush in Vietnam and an antiwar protest in Madison, WI, he covered all sides of the issue. But for his latest film, food companies such as Smithfield and Monsanto refused to cooperate. Lack of access became a part of the film, and he listed the companies that wouldn't participate. "Food turned out to be a subversive subject," Kenner says. "I would have had greater access if I were making a film on nuclear terrorism. Perhaps in making it I became progressively angrier because of the lack of cooperation and transparency."

To tell his story, Kenner elected not to use a narrator. Authors Eric Schlosser (Fast Food Nation) and Michael Pollan (The Omnivore's Dilemma) serve as on-screen guides and characters. "It's harder but more intimate when you don't have a narrator," explains Kenner. The problem is without a narrator "to change something is like moving a supertanker. You have to look through transcripts to see what people actually said."

After approaching a number of chicken farmers, one finally allowed Kenner in and he filmed with hidden cameras. And although Smithfield barred the door, company workers supplied some footage. So Kenner's challenge was finding the narrative in the 300 hours he shot over three years and combining it with industrial archival material. "If there's something that sticks out about Food, Inc., it's how to condense information," he says. "That's the battle. How do you get information across without putting people to sleep?"

The message might be serious but Kenner tried to set a lighthearted tone. For instance, the opening credits roll over supermarket images with cinematographer Richard Pearce's name appearing on a butter carton. "Even though it's going to be about weighty social issues, you can still smile," suggests Kenner. "These companies are selling the [idea of] the family farm. We show that it's on the supermarket walls, but it's totally false."

Images of cows raised in massive feedlots or chickens in huge, windowless rooms are unsettling, but Kenner was not trying to scare viewers, just to make them question the industrial system. Finally, he hoped to empower—and entertain—his audience while still delivering a message. For an interview at Virginia's Polyface Farm, where cows graze the old-fashioned way, he filmed using natural light. "To be able to go to Polyface and see those fields like that, you want to be there. So I wanted to figure out how to leave the viewer enjoying the movie experience—as someone said, making it delightfully distressing."

HUMANIZING: Davis Guggenheim hooked his audience with Al Gore's personal stories in

HUMANIZING: Davis Guggenheim hooked his audience with Al Gore's personal stories in

An Inconvenient Truth so the former vice president's cautionary tale about global

warming would get across and lead to action.

(Credit: Paramount Pictures)

Legendary British documentarian John Grierson once said, "The only reality that counts in the end is the interpretation..." And certainly all documentary directors interpret, to some extent, by filtering the real world through their lens. But directors tackling significant social issues have to take extra care about presenting the "truth." "No matter what you shoot, there's some element of things being crafted," Guggenheim believes. "Every documentary lands differently on that spectrum. My strong feeling is that audiences crave things that are genuine and they know when you're bullshitting them."

Documentary veterans Jon Alpert and Matt O'Neill (Baghdad ER, Access Denied? The Fight for Corporate Accountability), of New York's non-profit Downtown Community Television Center, are truth seekers. "Our documentaries are concerned with showing situations as they are," O'Neill says. "If we see corruption and pain, we show corruption and pain. If we see heroism, we show heroism."

They had no idea what they would find when HBO's documentary doyenne Sheila Nevins dispatched them to China after the 2008 earthquake rocked the country. They arrived eight days after the quake and considered returning home because they couldn't find a story beyond what was already being covered on TV. Then Alpert noticed a line of protesting parents clutching photos of their children, demanding to know why their schools collapsed. It became the heart of their documentary, China's Unnatural Disaster: The Tears of Sichuan Province.

The filmmakers stayed with the parents as they confronted police, and followed them to their villages and documented the shoddy construction of the schools. "The challenge was access," says O'Neill. "You see these intimate moments of grief with the parents. They wanted the story of their children told. The rage and grief were overwhelming. As a human being it's really hard to push in with a camera on a moment of intense personal grief, like when a mother communing with her dead daughter says she's going to fight for justice. What helps me push on in those really difficult moments is knowing this can reach a wide audience."

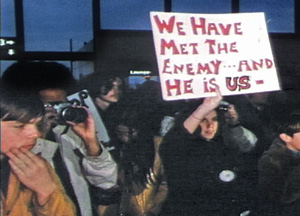

AIRBORNE: Robert Stone (above) traces the history of the environmental

AIRBORNE: Robert Stone (above) traces the history of the environmental

movement since 1970 in Earth Days. His message is that despite horror

stories and protests (top), things have gotten better. (Credits: Zeitgeist Films)

Sometimes making this kind of intimate film requires that directors pass up good shots to establish rapport with the subjects. "We wanted to make sure people knew we were not there to steal their soul and run away," Alpert says. "If a reporter or filmmaker seems like they're in a hurry, people can feel that. These parents saw that we were concerned. They looked in our eyes and trusted us."

To get close to their subjects—spiritually and physically—they used Sony EX1 cameras to capture "stunning images in a camera that is shorter than the length of my forearm," O'Neill says. But authorities noticed the cameras. When policemen questioned them, the filmmakers decided to courier their masters to New York. The next day, they were surrounded by 35 plainclothes cops. The police held Alpert and O'Neill for eight hours, interrogated them and asked for the footage. "When you get to say, 'I really wish I could show it to you, but I'm afraid it's already in New York,' it's a pretty good feeling," says O'Neill with great satisfaction. The authorities sent them home, not wanting to stir things up just before the Beijing Olympics.

Alpert, who has been shot at and detained in several countries, previously went undercover in China for a film called Snakeheads. Using a hidden camera and recording device, he filmed a local government official offering him $1.5 million to become a partner in human trafficking. "The greed of the local official and his presumption that I would be interested in money, too, made him completely unsuspicious. I was certainly nervous that the hidden camera I was wearing might be discovered but it wasn't. Sometimes in order to make these reports we're pushing or breaking local laws. It's really quite dangerous. You have to believe that there is a greater good that will be served that's worth taking the risk for."

Activist filmmakers can find their inspiration anywhere. Robert Stone's Earth Days was influenced by his own experience. He grew up in an idyllic New Jersey town, but saw industrial development displace farmland and pollution choke North Jersey and New York. Stone received funding from PBS in 2007 to make a historical documentary about the environment, starting with the turning point of the first Earth Day in 1970. "People [recently] have been getting bombarded with horror stories, but there was no context to them. There's a whole history people don't remember. People started to demand change, and things did get better."

He interviewed nine environmentalists, including former Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, Earth Day organizer Denis Hayes, astronaut Rusty Schweickart, and Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand. "When you're tackling a subject of this scale, the only way to tell it is through personal narrative. Everybody has a role to play that cycles back again and again."

AT RISK: Parents grieve the loss of their children in China's Unnatural

AT RISK: Parents grieve the loss of their children in China's Unnatural

Disaster: The Tears of Sichuan Province. Filmmakers Jon Alpert (middle)

and Matt O'Neill (bottom) knew their story could reach a wide audience.

(Credits: (top to bottom) Ming Xia/HBO; Shiho Fukuda; Peter Kwong)

Stone had hoped to conduct the interview outdoors but realized he would need more control over the sound and light. So he decided to film everyone on a soundstage against a black backdrop and then shot outdoor environments, compositing the backgrounds in After Effects. "We shot backgrounds at night. Then we'd set up lights in a similar direction to how we shot the interviews so the throw of the light would be similar. We added in crickets and atmospheric noise, but the rest of the time we had pristine sound. People who have seen the film are very surprised that [the interviewees] are not actually sitting outside."

Still, the interviews alone weren't telling the whole story, which, Stone says, is unfilmable. Then he had a breakthrough. In his interview, Brand described an LSD trip in which he imagined being elevated from a San Francisco rooftop into space, and spoke about how technology can enhance human perception, whether it's flying in an airplane, seeing Earth from space, or using stop-motion photography. This became Stone's "visual palette," and he incorporated aerials, NASA images, archival footage and animation.

"It's a way of getting out of our biological limitations to perceive things anew, which we have to do to tackle these difficult problems," says Stone, who hired a New York-based firm to animate Brand's acid trip. "Using the technology of cinema is perhaps the best way of presenting to an audience that different way of seeing things."

Stone was shooting things differently, too. In the past, he shot only on 16 mm film, but shot Earth Days in HD using the Sony EX3 and a Panasonic SDX-900. (He plans to try a RED Camera on his next film for even higher resolution.)

"In the past you'd just have a guy talking," Stone says of how docs used to be made. "You wouldn't be able to visualize it. Now you can. For $10,000 to $30,000, you can do a lot of animation. So many things that used to be only possible for big Hollywood movies are now available to documentary filmmakers."

Regardless of their technique, the thing that unites activist documentary directors is commitment to their craft and the knowledge that they are making films that can change people's lives. After watching An Inconvenient Truth, people went out and purchased solar panels and hybrid cars. In China, people tried to download China's Unnatural Disaster, but with little success. Then in September, despite efforts to suppress it, the film aired at the Beijing Independent Film Festival. The Chinese government blocked Alpert and O'Neill from attending. But, as with all activist documentaries, if the film gets people upset and challenges the status quo, then the filmmakers must have done their job.

Given the resistance, lengthy production process, and questionable commercial prospects, these filmmakers are clearly not in it for the money, but the rewards are more than financial. "The people in your films teach you so much about what life is all about, how incredible it is to stand up for the things that you believe in," Kopple says. "I am always changed, either intellectually or emotionally. You can't help it."

Crude ends with images of the Cofán people in a canoe, heading downriver toward an uncertain future, as the lawyers drone on. "I want the area to be cleaned up regardless of who wins the lawsuit," Berlinger says. "This 1,700 square miles of rainforest was supposed to be a pristine place on earth. But what oil production has done is just horrifying. Just witnessing that fundamentally changed who I was."