BY ANN FARMER

(Credit: Bayer Healthcare/Paley Center for Media)

(Credit: Bayer Healthcare/Paley Center for Media)

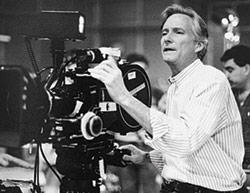

THE LIGHT TOUCH: George Gomes, who worked at several

agencies before becoming a director, was the master of the

nuanced, "indirect sell" in such landmark commercials as

the famed "I can't believe I ate the whole thing" campaign

for Alka-Seltzer. (Credit: George Gomes)

In the television period drama Mad Men, hardly a scene goes by when someone doesn't exhale plumes of smoke into the office air. The show's main characters—advertising men and women of the 1960s—also toss back more than a few martini lunches. But the actual advertising professionals who worked during that era are more likely to recall it as a fervently productive time on Madison Avenue, when advertising underwent a creative transformation that lasted well into the '80s and spawned many of the most inventive, iconic and successful ads of the last century.

"It was a golden time," says George Gomes, one of many DGA members who can boast of directing some hugely popular, award-winning commercials during those formative years of modern advertising. The Alka-Seltzer spots that he directed in the '70s with the still-familiar refrains, "Try it, you'll like it" and "I can't believe I ate the whole thing" rank high on a list of the 100 best advertising campaigns compiled by Advertising Age.

Number five on the list is the memorable McDonald's campaign launched in 1971, "You deserve a break today," for which Fred Levinson directed several spots. And who of a certain age doesn't remember the Volkswagen commercial from 1966 in which a coterie of circus clowns, a fat lady and an elephant amazingly emerge from a VW bus? While on staff as an agency art director, Ken Duskin helped create the concept and execution of that witty spot.

According to experts in the field, modern advertising began with a surprisingly understated ad campaign called "Think Small," which was created in 1959 by the seminal ad agency Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB). One TV spot featured a Volkswagen Beetle that drove into the picture frame and barely took up a corner of the empty, white space while a voiceover drolly extolled Volkswagen's pre-eminence in the field of small cars.

(Credit: Volkswagen Group of America, Inc./Paley Center for Media)

(Credit: Volkswagen Group of America, Inc./Paley Center for Media)

THE UNEXPECTED: Ken Duskin (with Chrysler's Lee Iacocca) learned

how to direct through trial and error, and helped create the innovative

Volkswagen commercial from 1966 in which a bunch of circus clowns, a

fat lady and an elephant emerge from a VW bus. (Credit: Ken Duskin)

That campaign represented a radical departure from the formal, predictable, preachy and hard-sell commercials of the '50s. Just as America's youth was rebelling against the establishment, Madison Avenue broke with tradition and began injecting commercials with more humor, irreverence, and storytelling techniques. Many of the commercial directors moved behind the camera after working at agencies as art and creative directors and played a key role in this revolution.

Howard Zieff, for instance, who died in February, began as a print photographer before establishing himself as a commercial and feature director with a deft hand for the comedic twist. "He brought a recognition of humor to commercials," says Levinson, referring to such spots as Zieff's 1969 commercial for American Motors' Rebel, in which a harried driving instructor barely survives his students going over the meridian and into a fire hydrant. For this and other spots, Time magazine dubbed him the "master of the mini-ha-ha."

"That period was loaded with talent—great, great talent," says Duskin, who described many of the directors from this time as New Yorkers who grew up in hardscrabble, ethnic neighborhoods where a high premium was placed on humor. Many aspired to be artists and went into advertising, which not only provided a creative outlet but yielded on-the-job-training for future directors.

"None of us knew anything about making film or shooting commercials," continued Duskin, who originally wanted to be an illustrator. His first job in 1948 was as an art editor for True Confessions magazine. Later he was hired onto the creative teams at agencies including DDB, where he learned, through trial and error, what worked and what didn't. By the time he began directing, he says, "I knew film cutting and editing. I knew how to direct actors. And we were developing new lighting techniques."

Gomes also sprang from the creative ranks of DDB, where he served as an art director while working on such prestigious accounts as American Airlines and Volkswagen. Then he got a yen for directing. "Without thinking it through carefully, I quit and announced myself as a commercial director," says Gomes, who was a fast learner and quickly discovered that his nuanced understanding of how to sell something (what the trade calls the "indirect sell") gave him a leg up with clients. "It was always the product you had to respect," says Gomes. That's what gave me a real boost." He went on to earn 22 Clios and the DGA Award for outstanding directorial achievement in commercials.

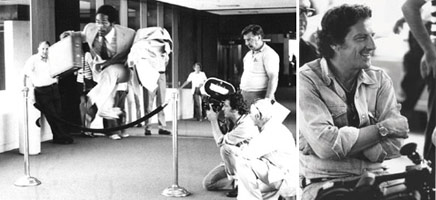

THINKING FAST: Fred Levinson (above, with camera), who started out as a cartoonist,

THINKING FAST: Fred Levinson (above, with camera), who started out as a cartoonist,

used his skill as an improviser to help develop the character on such spots as a Hertz

commercial with then-popular sports figure O.J. Simpson. (Credit: Fred Levinson)

Ad agencies, meanwhile, were restructuring their organizations to enhance the potential for innovation. They replaced management professionals with creative types who better understood the contributions a director could make. Independent directors were invited to bid on projects and were encouraged to work closely with the agency's writers, art directors and creative directors, who would solicit their input from preproduction through postproduction. Directors, in fact, were routinely allowed to edit their own cut, something no longer common today.

"We were part of the creative team but we'd never advertise as such," says director Fred Levinson, who began his career as a cartoonist before becoming a director and opening his own boutique production house in the early '70s. As a director, he received numerous Clios for such memorable baby boomer commercials as AT&T's "Reach out and touch someone" campaign and Virginia Slims' "You've come a long way, baby." A re-election film he directed for Ronald Reagan was hailed by The New York Times as "the most luxurious, symphonic and technically proficient political commercial ever made."

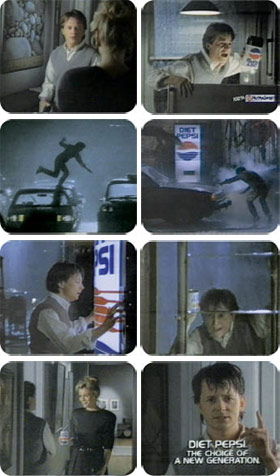

THE HUMAN TOUCH: Rick Levine was known for bringing feature film

THE HUMAN TOUCH: Rick Levine was known for bringing feature film

production values to elaborate spots such as a Diet Pepsi commercial

featuring Michael J. Fox running through the street looking for a vending

machine. (Screenpulls: Pepsi-Cola Company; Photo: Rick Levine)

Typically, after the agency hired a director, he would go over the initial storyboard and then meet with the agency's creative team to discuss the best way to execute their plan, including ways to take the concept further. Levinson often met with the team two or three times before going into production.

Gomes, who after working at several agencies in the '60s, co-founded his own production company, recalls attending a storyboard meeting to direct a Crest toothpaste spot in which the initial mock-up looked rather humdrum. "I said, 'Why not dress people up as teeth?'" He got the directing job and subsequently designed some bold costumes for a humorous scene in which one actor, dressed as a big tooth, says goodbye to another that's going to be pulled out because it's decayed. "The costumes were the thrust of the commercial," says Gomes, adding, "It was never meant to be, but it became a hit."

Shooting was also less formal, says Levinson, and directors could easily put their creative mark on something. He recalls, for instance, how he influenced a successful Hertz ad from the mid-'70s that featured O.J. Simpson when he was still a popular sports figure. "I improvised that stuff," explains Levinson, referring to a scene in the departure terminal in which Simpson leaps over lounge seats to get to his rental car and a woman yells "Go O.J., go!" Levinson says that line wasn't included in the original storyboard. "I thought, 'It's O.J., you've got to develop his character.'"

Rick Levine was a successful art director at DDB before opening Rick Levine Productions in the early 1970s. He subsequently directed commercials about everything from Wendy's hamburgers to PRO-Keds. "If I had the confidence of the clients, they'd let me pour myself into it," he says, describing how he'd often ask to do a preliminary "shoot-board" to breathe life into their ideas. "I'd come up with lines, thoughts and touches," says Levine, who received dozens of Clios and twice won the DGA Award for outstanding directorial achievement in commercials.

Levine was known for creating kinetically exciting scenes and coaxing affecting performances from his actors. "Now it's considered corny, but I always wanted to touch the heart of another human being," he says. His "Apt. 10G" spot for Diet Pepsi worked so well as a visual spectacle and feel-good piece that it's included in the Smithsonian Institute's permanent Americana collection. It features a young, sympathetic Michael J. Fox racing through a dark and stormy night to procure a Diet Pepsi for his attractive new neighbor. Levine nixed using a set. Instead, he shot it on the streets of New York for three days in the pouring rain. The most dramatic scene—when Fox jumps off a fire escape into a traffic jam and runs and slides across the tops of cars (performing his own stunts) to reach a vending machine—had the production values of a motion picture. "We decided to make our ads look as good as films," says Levine. "I would direct and shoot," says Levine, "so I would have complete control."

When he shot a Wells Fargo commercial in the late '70s for McCann Erickson, he built a temporary town with 25 to 30 buildings outside Sedona, Arizona, and then slowly burned it down over three days. He used five cameras with three fire departments standing by. He employed at least 500 extras, and most surprisingly of all, he invested $200,000 of his own money to do it right. "Sometimes you had to invest in your own reel," he says, describing how they worked through the night to catch a shot of the stagecoach leaving town with the sun coming up and trickles of smoke rising from the embers. "I had a lot of fun," he says. "I used to fight passionately for everything I did."

NATURAL LOOKING: Melvin Sokolsky used the sharp eye he developed

NATURAL LOOKING: Melvin Sokolsky used the sharp eye he developed

as a top fashion photographer for Harper's Bazaar to cast engaging real

people for commercials like his award-winning spots for Dr. Pepper.

(Credit: Dr. Pepper/Seven Up, Inc./Paley Center for Media; Melvin Sokolsky)

In those days, everyone was trying to come up with big ideas "that really blew it away," says Neil Tardio, who worked his way up the ladder at Young & Rubicam to the position of associate creative director before founding his own production company and directing award-winning ads for such major companies as IBM, American Express and AT&T. He even stepped in front of the camera at times—acting the part of a high-powered executive for E.F. Hutton commercials.

Like many directors of that period, Tardio developed into a skilled storyteller. "There was a method of drawing the viewers in," he says, explaining that, while commercials today are routinely 10 and 15 seconds long, they were commonly at least 60 seconds then. He directed 90-second commercials for Eastern Air Lines and Pan Am and even made a three-minute underwater commercial in 1967 for Union Carbide that required shooting in a research submarine.

The longer format allowed directors more time for setting a scene and creating characters, weaving a compelling narrative and providing a satisfying payoff. For instance, Tardio's endearing "Monks" ad for Xerox in 1976 opens with an overworked monk painstakingly transcribing an ancient text by hand. When his supervisor orders 500 more copies, the monk sneaks out to the neighborhood copy shop to have a Xerox machine complete the task. "It's a miracle," exclaims the unsuspecting Father Superior, gazing heavenward after receiving the stack.

Tardio carefully studied the actors during rehearsals and decided to boom down on the stack of Xeroxes just before the Father Superior looks up, thus providing a visual counterpoint and extra kick at the end. "The client said, 'Are you sure that's the right thing to do?' We looked and it was. People in the room were laughing. That's when you know it's in the can." Later, when he edited the spot, he recalls, "It cut like butter."

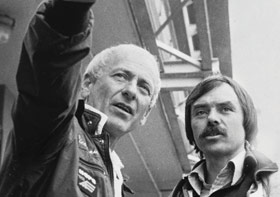

STORYTELLER: Neil Tardio (left) directed spots with Lee

STORYTELLER: Neil Tardio (left) directed spots with Lee

Iacocca that helped resurrect Chrysler. (Credit: Neil Tardio)

Tardio also had a talent for working with actors in such

commercials as hisendearing "It's a miracle" campaign

for Xerox in 1976. (Credit: Xerox Corp.)

Tardio developed a facility for coaching a wide range of actors, non-actors and celebrities, including Chrysler CEO/spokesman Lee Iacocca who was featured in ads that helped resuscitate the failing automaker. "You bring out things they didn't know they had," he explains.

But it wasn't just human personalities that these directors had to deal with. They needed a whole range of tricks up their sleeve. Fred Levinson, who believes he shot as many as 150 commercials one year, still recalls the tight spot he got into with a Purina dog food commercial for which he audaciously created a storyboard shot where a dog smiles. Sure enough, when he tried to wrap without it, the client intervened, saying, "No, that dog has to smile," recalls Levinson. So thinking fast, he ran out with a jar of peanut butter and rubbed some on the roof of the dog's mouth, causing it to stick in place. "I stepped away and told the cameraman to let it roll. The dog's upper lip went up and it looked like a big smile. No one could believe it. I went back to my office and said, 'I did it. I'm a fucking genius.'"

The spirit of innovation that swept this period made it possible to take chances on unproven talent. Melvin Sokolsky was a top fashion photographer for Harper's Bazaar when he got a call from an ad agency creative director. "He asked if I could do on film what I do in still pictures. I said, 'I don't know.' He said, 'If I gave you money, would you try?'" Sokolsky went on to engineer all types of novel lighting setups, using things like fluorescent tubes, Chinese lanterns, and natural lighting, which were considered experimental at the time. His award-winning commercials for Dr. Pepper enhanced his reputation for having an astute eye for casting. He used real people, who came across as naturally engaging instead of using stereotypically good-looking actors.

But all revolutions eventually come to an end. The intense creative momentum that ushered in the '60s began to wane by the late '80s, or perhaps gave way to a new type of advertising.

To be fair, says Tardio, "every generation thinks they do the best work. But we were lucky. It was a privilege to be in the business at that time. The people we worked with were bright. They were trying to achieve good stuff that communicated well. It was a great, great time."