BY LISA SCHWARZBAUM

Photographed by Paul Schirald

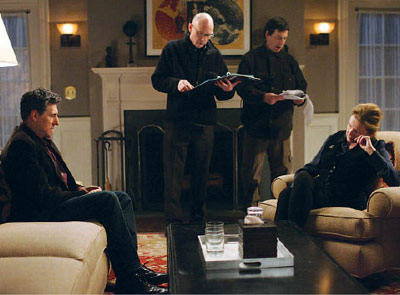

GROUP THERAPY: Director-executive producer Paris Barclay (2nd from

GROUP THERAPY: Director-executive producer Paris Barclay (2nd from

right) gets to the emotional center of a scene with actors Gabriel Byrne

(right) and Dianne Wiest (left), assisted by 1st AD Richard Patrick

(seated) and writer Marsha Norman.

For a psychiatrist and patient hard at work in the excavation and analysis of a psyche, the space in which that collaborative work takes place can feel like a cocoon, a playpen, a biosphere designed to promote change and growth. For a director shooting an episode of In Treatment, the HBO drama series about a shrink and his patients, now in its second season, that same room can feel like... well, if not exactly a prison, then certainly a puzzle requiring its own tough analysis. How do you make a set that's essentially one room, a box in which two people sit and talk, feel as alive to the eavesdropping, voyeuristic viewer as it is to the characters, engrossed in their own dramas?

"In a way it's about resisting all of the things that other shows ask you," says executive producer and director Paris Barclay. And on a cold, sunny February morning at Silvercup Studios in Long Island City, he demonstrates how.

In Treatment, based on the wildly popular Israeli TV series Be' Tipul, follows the personal and professional struggles of Dr. Paul Weston, a flawed middle-aged man in crisis, played with soul (and a surprising native Irish accent for his profession) by Gabriel Byrne. Last season Paul, a married father of three, fell in love with a patient—the ultimate professional taboo—and although the relationship is over, so is his marriage. Last year, too, another patient died, an anguished soldier in what was possibly a suicide. Now the dead man's father is suing the doctor for malpractice. Everything, in fact, is new and unsettled in Paul's life this year except his connection to Gina, a fellow psychotherapist, played with authoritative ease by Dianne Wiest. Over the years, Gina has been Paul's own counselor, clinical supervisor, and friend. Now she's his shrink again.

FACE TO FACE: Director Jean de Segonzac (center), with Byrne (left),

FACE TO FACE: Director Jean de Segonzac (center), with Byrne (left),

Richard Patrick and Dianne Wiest, has about "4,000 notes on every

page" as he tries to create action through the drama of the scene.

Today, Byrne and Wiest, as Paul and Gina, are about to lose themselves in a scene exploring Paul's pain. With his divorce, viewers have been told, Paul has moved from Baltimore to Brooklyn, and he sees Gina when he takes the train to visit his children. The set that is Gina's home office, meanwhile, retains much of its original, familiar seashell-neutral, subtly feminine tones. The vivacious Barclay, who joined the production in the middle of the first season (when the show was shot in L.A.) after stints on more kinetic productions including The Mentalist and Cold Case, has just spent a long time in low conversation with his actors—a kind of shrink session of his own, clarifying the emotional beats in the episode.

Finally he calls Action!—an ironic word, considering how much is spoken and felt, but how little qualifies as, well, action on this uncompromisingly adult show. Wiest, settled on a couch, fingers a pair of eyeglasses and touches a pillow. Byrne leans in and shifts slightly in his chair as if to relieve pressure on a psychic bruise. And as the characters burrow into the profound, essentially immobile activity of "treatment"—the actors thinking, speaking, pausing, and not budging from their seats in an uninterrupted take that runs some 10 minutes—only hyper-attentive study of the monitor reveals the dynamic secret of the scene's effectiveness: While appearing to be a study in motionlessness, the room is alive with emotion.

To capture that moment, Barclay has selected a medium two-shot that incorporates the world's slowest pan. The shift is as gentle as breathing, a nearly invisible reshaping of space that expresses the creeping pace of psychological progress. It's a move at once gorgeous and unnoticeable to an average viewer's eye.

Each of this year's roster of 13 directors is encouraged to find his or her own solution to an In Treatment puzzle as confounding as an eternal Freudian struggle: How to externalize internal change.

"Each [director] frames differently, each positions the camera differently, each favors different aspects of the rooms," Barclay says, sprawled in a chair during a break in a sparely furnished, backstage den identified with a bright pink sticker on the door as "Camp Paris." "I thought that every episode should have something that helps emphasize or underscore or heighten what the story would be. But it has to be very simple."

For example: In the story line about Paul's patient Oliver (Aaron Grady Shaw), an anxious boy caught between warring, divorcing parents, director Ryan Fleck subtly echoes the child's emotional squirms. "It's not handheld, but it almost feels handheld because he uses a lot of loose camera on the dolly," says Barclay. Other examples proposed in Camp Paris: Terry George "is very, very meticulous and spare about how he moves the camera." His work with the character of Gina is notable for its simplicity of style. "I was talking with [guest director] Michael Pressman," Barclay goes on, "and he said this is the show where you try not to do anything. It's about focusing on performance, focusing on the needs of the story and trying to be as unobtrusive as possible."

Director Jim McKay has a general discussion with Alison Pill before a scene

Director Jim McKay has a general discussion with Alison Pill before a scene

about what she's trying to achieve.

Jim McKay, who arrives on the case this season after directing episodes of Big Love and Law & Order, restates the In Treatment credo: "If I had a goal, it is to make the camera invisible. On this show, I've tried the longest and slowest dolly move I've ever done. The camera's movement has to correspond to something. I want editing you don't really notice."

Barclay, who directed stage plays and musicals before his TV career, says a feel for the sensibilities of live drama helps, too. In his role as a producing director, "I always ask [potential directors] about the theater. And if they say they don't really go, then I don't think they're really right. I can't imagine a director who doesn't go to the theater having the patience and ear for this kind of dialogue."

An indie film sensibility, with its emphasis on character development, is also a plus. Directors with the patience and ear for this year's seven-week run include Pressman (Come Back, Little Sheba on Broadway), Fleck (Half Nelson), George (Hotel Rwanda), and Courtney Hunt (Frozen River). Also on board are McKay (Big Love), Alan Taylor (Mad Men, The Sopranos), Jean de Segonzac (Law & Order: Criminal Intent), and Richard Schiff (The West Wing)—all of them entrusted with sustaining a schedule that runs on the very opposite of a theater clock.

Each episode is shot on HD tape in two days, an average of 10 dialogue-dense pages a day, to keep pace with the unique, five-nights-a-week broadcast pattern In Treatment inherited from the original. (Each Israeli episode was shot in a day.) Here, after all, are seven weeks of more-or-less actual therapy in more-or-less real time, as Paul works with the same patients week after week—Patient A each Monday, Patient B each Tuesday, and so on—then engages in his own therapy session each Friday.

"But don't forget, the theater directing process is to work it and work it over four weeks," says executive producer and showrunner Warren Leight. Like many In Treatment writers, including Marsha Norman, Sarah Treem, and Keith Bunin, Leight (Side Man) is a playwright at his core. And like many involved with the show, he's ready to talk about the material with a personal interest and familiarity that can't be so easily assumed, let's say, on a show about cops or docs. (Case in point: As Barclay discusses the integrity of a certain line of dialogue with Norman and Treem, a behind-the-scenes observer chimes in, "My shrink said something like that." A consulting professional is also available as a technical advisor to discuss the finer points of, for instance, whether Paul and Gina would hug upon seeing each other again in the first episode of the season. The ruling: No. Therapists would not hug.)

"Here," Leight continues, "it's like rehearsing a piece and shooting it in two days. So I also need a director with a lot of technical expertise, because I can't risk not having a scene covered—there's no time to go back. We need people who can make the day."

Using the template set by the original Israeli production and imported by executive producer and season one showrunner Rodrigo García, each writer sticks with the same character throughout the series, but the directors' caseloads are likely to move from character to character. This season, Leight is stressing looser adaptation of the material rather than the narrower translation of Israeli episodes that characterized the first season.

And to up the level of difficulty, the episodes are likely to be shot out of order to accommodate the work schedules of a cast that, this year, also includes stage actors Hope Davis and Alison Pill. As a result, organizational direction becomes even more crucial for the cast than motivational notes. "During prep, you section the script into three to six parts that are four to eight pages long—the arc of an act," McKay explains, "and during shooting you don't really have time to do adjustments, but you spend a lot of time monitoring the flow." In order not to interfere with an actor's process, "we have a general discussion about what the character is trying to achieve in his session. And with Gabriel, we may discuss how aggressive he might be with his patient and his strategy as a therapist."

1st AD Richard Patrick runs the set and keeps

1st AD Richard Patrick runs the set and keeps

things moving while 2nd AD Jane Ferguson

preps new directors as they start work.

First AD Richard Patrick acknowledges the additional burden on the director's team. "It's part of the director's prep to know what has happened in the past, and for everyone to be aware of the arc of the character. And then there's Gabriel Byrne, who is in every single scene. He's got to come to work each day and embrace the full plate of work and he may not even know what happened prior."

In addition to an effective operating system of prep work and a regular regimen of tone meetings, one solution that works for the directorial revolving door is to employ one team of ADs. "That's unique," says Patrick, who works with 2nd AD Jane Ferguson. "I'm continuity and I run the set and keep things moving forward, while Jane anticipates the prep of the new director as he or she comes in. Together we bring [new directors] into the fold in terms of how we do things. At the end of an episode, there's always a wonderful moment of what I can only liken to live theater, where we always applaud the cast and the director. And then we go on to the next day's work.

On another frigid morning with winter howling as stubbornly as a patient in denial, Jean de Segonzac is shooting a hospital room scene between Byrne and John Mahoney as his Thursday patient, Bill, an unraveling businessman. The character of the proud, overwhelmed company biggie is the tonal opposite of the actor's famous, sitcom-smooth work on Frasier. The hospital setting is already a departure from the show's more familiar surroundings, and it's a stop-the-presses novelty when an extra appears for three seconds, a nurse bearing a tray. ("An action sequence!" Barclay later confirms with a laugh.) Observing the scene being shot, Leight has a go at explaining the directorial conundrum this way: "The utter absence of movement isn't good, yet the overuse of movement is intrusive. You don't want to sense anyone else in the room. It should just feel like the two people."

Later, during the lunch break, de Segonzac analyzes his own approach. "I was told not to bring attention to the camera at all," he explains, "so that adds to the difficulty. The real action for me becomes how to—I don't want to say push the actors, but to create action through the drama of the scene itself; it can be quiet, but also there can be opposition, a conflict. It's true, I like making a ballet for the camera, and I like to move the camera. So for me, I like to place the camera so it gets interested in what's going on, and we get closer and closer and closer. I like a camera that's thinking, one that's responding to what's being said." So in his own private, off-limits conversation before the cameras roll, the director urges the actor to get feisty, like a boxer in the ring. "I try to get as much fight out of my patient as possible," de Segonzac confides.

"Jean's script," says Leight approvingly, "has got 4,000 notes on every page. He understands that on this show, it's all about subtext. If you limit creative people, they explode within the limitations."

Freud called psychotherapy "the talking cure" for a reason. The process is slow, and sometimes gets stuck. It's drawn out, and it grinds on week after week. The work can be profound, intense, and dramatically life changing for those on the therapy couch and in the analyst's chair. But perhaps only one director to another can appreciate the professional alchemy involved in making the In Treatment audience feel like intimates. When, in a lurching conversation between Dr. Weston and his own confessor, Gina, Barclay directs a camera move so minuscule as to feel subliminal, all of us are invited to sit on the other side of a one-way mirror and watch souls in the process of reconstruction, sometimes without moving a muscle.