BY AMY DAWES

Photographed by Melinda Sue Gordon

With her fifth film as a director under way, Nancy Meyers is becoming a torchbearer for a kind of sophisticated, stylish, and upscale romantic comedy that is in short supply nowadays. After nearly two decades as a screenwriter and producer, her track record as a director has been remarkably consistent. The reliable pleasures of Meyers’ movies include A-list actors, enviable locations, and a classic approach to filmmaking with a nod to the screwball traditions of Hawks, Sturges and Wilder. From What Women Want to Something’s Gotta Give, her films give hilarious voice to the pressures, predicaments and conundrums facing contemporary relationships.

With her fifth film as a director under way, Nancy Meyers is becoming a torchbearer for a kind of sophisticated, stylish, and upscale romantic comedy that is in short supply nowadays. After nearly two decades as a screenwriter and producer, her track record as a director has been remarkably consistent. The reliable pleasures of Meyers’ movies include A-list actors, enviable locations, and a classic approach to filmmaking with a nod to the screwball traditions of Hawks, Sturges and Wilder. From What Women Want to Something’s Gotta Give, her films give hilarious voice to the pressures, predicaments and conundrums facing contemporary relationships.

Carving out time with Meyers during the intense preproduction period for her latest project proved no easy task. Not surprisingly, a location visit to a bakery in New York’s Chelsea Market days before shooting revealed a picture-perfect set—from the warm brick walls and the marble counters dusted with flour, to the giant mixing bowls and racks of eggs. Meryl Streep, playing a bakery owner, drew a crowd at the window as she was given a quick lesson in cutting pastry dough. Once she left, Meyers got down to the nuts and bolts of blocking the scene. “Let’s talk about what we’re going to see in the Steadicam shot in terms of business,” she said, conferring with her longtime collaborators. The atmosphere was low-key and friendly, and Meyers’ level of organization and attention to detail was impressive.

She describes the still-untitled project as a romantic comedy about a woman (Streep) who finds herself torn between two suitors (Alec Baldwin and Steve Martin), one of whom is her former husband. Despite the fact that the film is set in Santa Barbara, we finally met up to talk the next day at the film’s production office in Brooklyn.

Nancy Meyers has captured the rhythms of modern relationships in films like Something’s Gotta Give and What Women Want. In her latest picture, she again finds food for thought.

Amy Dawes: You’re only three days away from shooting your new movie. What’s the pre-production stage like for you?

Nancy Meyers: Prep is everything. I love every part of it. I don’t mean I actually love doing it, but I love having done it, and at this point we’re 99 percent there. We had a production meeting yesterday, and it took an hour and 10 minutes. There were very few questions left to answer. We’re 12 weeks into it, and at this point we’ve done so much work, had so many meetings, been here so late at night for so many weeks…

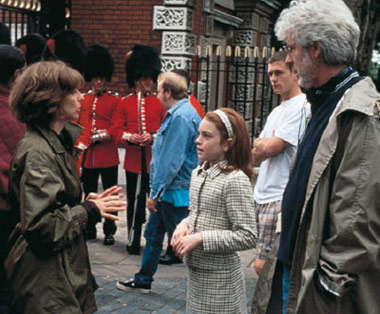

KID STUFF: Meyers, with producer/co-writer Charles Shyer (right), directing

KID STUFF: Meyers, with producer/co-writer Charles Shyer (right), directing

her first feature, The Parent Trap, starring a young Lindsay Lohan in the

dual role of twins. (Photo Credit: Walt Disney Co./Everett Collection)

Q: What are some of the last things you’ve been doing? I see there is still auditioning going on today.

A: Casting is the most time-consuming part of prep. I’m almost done with that. And then finding the locations, designing the sets, decorating the sets, and wardrobe. Everything is a part of continuing to tell the story, so you’re constantly defining what’s in your mind to every possible department. At this point, I’m become tired of my own voice. But they want to know, and they need to know.

Q: How involved are you in casting?

A: Well, the director casts the movie, that’s part of the job. It would be embarrassing for me to tell you how many people I see, even if the person has one speech, or one line or moment. I try really hard to find people who can execute the movie and deliver tonally what I’m after, and people who will play well off of each other. It’s really important to cast funny people in a comedy, and ‘kind of funny,’ or ‘makes you smile’ isn’t the same as really being funny. I’ve learned that over the years.

Q: The storyboards I saw were very exact, down to the lines of dialogue spoken in each frame. Do you always storyboard your movies?

A: Yes, it’s the very first thing I do, it’s pre-prep. I work on the storyboards for two hours daily, and it’s the one thing I try not to let them take out of my schedule. And I’m on my third draft [of storyboards], since we revise them as we find the locations. Everybody gets copies of the boards, and everybody gets copies of the revised boards. Every Sunday I send a mass e-mail to every department about anything that’s changed, so everybody knows everything. I bet there are fabulous movies that don’t storyboard, and don’t do the research and this kind of prep. But I don’t think I’d be good at doing one of those. For me, and for my personality, this is the way I like to do it. People do their work the way it works for them.

Q: Is there a point in the process of getting a movie on its feet where you feel like you can breathe, like you’re there now?

A: I would say…after a preview. After an audience sees it.

Q: So it’s not as if, at the end of the first day on set, you can take a deep breath?

A: I do feel ready to get there. But then there’s a whole new set of stuff to worry about. We just finished our camera and wardrobe tests. Everybody’s testing their stuff. The DP is figuring out how to light Meryl Streep: how little light can she take, how much is too much. I’ve had rehearsal, but not a lot—one day with Steve Martin and Meryl, and one day with Alec Baldwin and Meryl. I would like to have had a little more; I didn’t even get through the whole script with them.

Q: For years you were in partnership with your ex-husband Charles Shyer as a producer and screenwriter. At what point did you know you wanted to move into directing?

COMIC TIMING: In What Women Want, Meyers (left) directed Mel Gibson

COMIC TIMING: In What Women Want, Meyers (left) directed Mel Gibson

and Helen Hunt as sparring co-workers in the style of screwball comedies.

(Photo Credit: Paramount/Everett Collection)

A: Well, Charles and I were a team for a long time. We wrote together and he directed all of our films, from the second one on. And we had young children so I hadn’t really thought about directing, because I knew from living with a director what it took. But in the late ’90s, when my youngest daughter was 11 and my oldest daughter was 18, it seemed like a natural progression. Also, I had been a producer on all of our movies, and I think by then I had gotten a little bored with that.

Q: In making that transition, were there certain areas of directing that you found particularly challenging?

A: Well, I had made a lot of movies by the time I did it. From 1980 to 1998 I had been on the set of my own films as a screenwriter and producer. So in 18 years of making movies I had faced a ton of situations. But no matter how many times you’ve been in the car, it’s a little bit different to be driving it, that’s for sure.

Q: That first movie was a remake of The Parent Trap with Lindsay Lohan, who was then an unknown, in the dual role of separated twins. Did you have any sense she would become such a big star?

A: Well, Lindsay was a real find. She was absolutely great; she played those two parts with a real clear delineation, not mixing up her characters. I remember at the end of the first preview, Michael Eisner was standing by the candy counter in the theater and he said to me, ‘You’re so lucky, because in the original we had just one kid. You were so lucky to find these girls.’ [laughs]

Q: Was it difficult to deal with a split-screen process on your first film?

A: It’s done with motion control. It was complicated, and I really didn’t know how to do it. We had a prep day to go over the process, and by the end of the day I had a little better understanding. But I approached the movie like it wasn’t an effects film; I just tried to make it authentic. I had a very good DP, Dean Cundey, who’s done a lot of effects films, like Who Framed Roger Rabbit and Jurassic Park. He was the absolute right guy for me and really helped me. Had I really known what it was going to take to do it, it probably would have scared me off. We had to do everything twice, and on children’s hours. But the complexity of the motion control work became oddly fun. It was a fun challenge to figure it out. Since I didn’t know the restrictions of what could be done and what couldn’t, I would ask for things that, had I known better, I wouldn’t have. And because Dean was up for it, we kept doing it, and I think that’s why the movie feels alive. We were schlepping all that equipment down mountainsides.

Q: There are a lot of locations in that movie.

A: And it’s a big caravan to try to haul that stuff. But that’s the thing about being a director. You ask for it, and everybody tries to give it to you. So my naiveté about the process really helped me.

Q: Your 1st AD, K.C. Colwell, has worked on all your movies, including the one you’re shooting now. Can you talk about how you interact?

A: He’s the go-to guy for us, he’s the one who’s got the day in his head in every possible way, and helps me make it happen. On this movie, he’s been making shot lists for the first time. He does that every night, and gives all that info out to everybody, which has been fantastic. And he never forgets a thing. If I say, ‘K.C., remind me at the end of the day…,’ he reminds me.

Q: This is the fourth time you’re working with your production designer Jon Hutman. How does that collaboration work?

A: It’s amazing what production designers do—the research and the effort and the detail never cease to amaze me. As a director, you go with the location scout and look at an empty room and say, ‘Okay, this can be the newspaper office where the character works.’ And then months later you come back and it’s a full-blown newspaper office, down to the clocks on the wall and the newspapers on the desk. Jon can design a great movie house, which is very important to me. I can spend 40 pages between the kitchen and the living room. Jon adds scope. He’s a very hard worker, has very good taste, and he’s a fast e-mailer. [laughs] He enjoys the process, and it is a process—things evolve over time. Some people are just, ‘This is what I’m doing, and I’ll see you when it’s done.’ But Jon is very open.

Q: Even going back to the Father of the Bride movies that you co-wrote, it seems like your characters always live in places that are picturesque and lavish. Can you talk about how you use set design?

A: My movies take place so much in the environment of the house. On Father of the Bride, [the studio] said, ‘We want the wedding in the house.’ That’s a big scene that takes place there. And on Something’s Gotta Give—in my mind, that was a movie about, ‘What if these two people were stranded on a desert island? Would he eventually fall for her?’ [laughs] So the house was the desert island, and I wanted to create a place where this love could bloom. It was a beach house in the Hamptons that we actually shot on a stage in Culver City, and it was really fun to create that.

Q: In your new movie, the house that Meryl Streep’s character lives in actually changes, much like a character might change.

A: Yes, because the remodeling is the reason she meets Steve Martin’s character. She’s bought the house after her divorce, and has been putting her money into her business, so I pictured it as a little too small for her. I took all the walls out, so it’s one big room from the kitchen to the dining room to the living room, because she’s got three kids, and she would want it that way. It’s got a very loft-like feeling, but in a classic adobe house in California. She’s a chef, and now it’s 10 years after her divorce, so she’s ready to expand, get a big kitchen. Steve Martin plays the architect who’s designing her expansion and they get into a relationship.

Q: Is any part of the story set in New York?

A: None. [laughs] It’s set in Santa Barbara. She lives on this lush acreage in the hills above the city.

Q: How did you end up shooting in New York?

A: Well, it’s a long, complicated story. There are many reasons, but the tax break is a big one. I wish we had that in California. I mean, I live in Los Angeles and it would be nice to work there. But we are shooting for a month in L.A. and Santa Barbara.

Q: So is that why you have this big board above your desk covered with magazine photos that suggest the location?

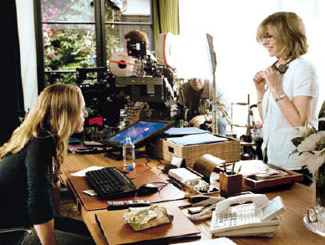

OFFICE JOB: Meyers, directing Kate Winslet in The Holiday, worked closely

OFFICE JOB: Meyers, directing Kate Winslet in The Holiday, worked closely

with her production designer to create an authentic, lived-in environment.

(Photo Credit: Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.)

A: Yes, it’s because I’m in this industrial part of Brooklyn making a movie about Santa Barbara, so it’s a lot of images of the countryside. And she runs a restaurant-bakery, so there are a lot of food images. People come into the office, so I put images up there to keep what we’re doing current in everyone’s mind. You know, directing uses such a different part of your brain. When I’m writing, I can just write, ‘Jane enters her small but comfortable home…’ but when I’m directing, I have to translate that sentence to a house that has to be built. I walk onto the stage and there’s literally a hundred-person crew on the set building that house. So I use images a lot. I’m not short on words, God knows, or e-mails, but I make photo files in iPhoto on every character and every set.

Q: You do that on your Mac?

A: Yes, and I actually make books of images that I’ve collected and give them to people. Some I’ve collected while I was writing, and some that I start looking for once I know I’m going to direct the movie. I go into iPhoto and drag a bazillion pictures into it. It can be a photo that I’ve pulled of a man on the street in Rome, but he’s got a certain hat that reminds me of Alec Baldwin’s character. I’m not really saying please buy him this hat, I’m just saying it has a feeling, an attitude.

Q: So these are visual reference points?

A: Yes. They could be photos of architectural things to give to the production designer. People really want to help you, they want to get into your brain, and I’ve found that this is a great way. The screenplay speaks for itself, but I do find that having these collections of reference photos has been a very helpful tool for a lot of people.

Q: How do you establish a working relationship with your actors when you haven’t worked with them before? For instance, this is the first time you’re working with Meryl Streep.

A: Well, we’re just getting started, so I haven’t really directed her yet. But that’s what’s great about prep—you get to prep the movie with your actors. The part they’re involved in, of course, is wardrobe, and that’s where you have your initial interactions with them. So on wardrobe day I began to see how Meryl works. There’s a dress that she wears on a date, and what she loved about it was how it moved, and when she gets uptight during the scene she can close it up. She’s very interesting to work with; I’ve gotten to see the character coming alive. I would see how she looked in the mirror and started to become her. We just talked and talked for hours. You’re talking about the intent of the scene, and the way I envisioned her looking to make the point of the scene. Especially with women’s clothes, it’s things like, ‘How sexy does it become? What do you reveal?’ Rehearsal isn’t always rehearsing a line. Sometimes you’re just talking about shared experiences.

On Something’s Gotta Give, I remember my first wardrobe fitting with Jack Nicholson took six hours, and he tried very few clothes on, but we talked for hours about his character. He’s a very smart guy; he had very good ideas. They weren’t always the same as mine, but we talked about differences in the way of seeing the characters. Wardrobe fittings, I find, are a great and helpful tool, because you hang out with the actors for a long period of time and start talking about the scenes.

Q: When it comes to the performances in your movies, I notice there’s a lot of physical comedy. In The Parent Trap, you had a really cute little dance and handshake that Annie does with her butler. How did you develop that?

A: Well, I do think about it when I’m writing. There’s a dance and a little secret handshake in the script. Then the actor adds the bump, so it grows a little.

It’s not the kind of thing you write for an actor who can’t do it. This is my third movie with Steve Martin, and he’s fantastic at it. He’s brilliantly funny verbally, but also a very good physical comedian. Cameron Diaz is also someone who does funny things very easily.

Q: There’s a scene in The Holiday where she enters the house after her breakup and she’s sort of coming apart and pumping her fist.

A: Yes, she was sort of having a fit. I remember in the Carole Lombard movies how she was just so physical. She would throw herself on the bed, throw herself into someone’s arms. I remember talking to Cameron about that kind of physicality, and that I saw the character using her body in that way.

Q: Let’s talk about those screwball comedies. I know they’ve been an influence on your writing; have they informed your style as a director too?

A: I think the best thing to learn from those movies is the pacing and timing. The actors seemed to know the dialogue really well, and they were on the words in a way that made those movies fly. I love the sound of those movies; to me it’s like a certain kind of music that I love. The writing is superb; the sophistication of the dialogue and the relationships; the sexuality that was always there between the couples. Also, the speed at which the dialogue was delivered was really fun to watch. There wasn’t a lot of improvisation that I can think of in those movies.

Q: Do you ever use improvisation on your films?

A: I like to stick to what I’ve written. I really don’t believe in the moment. I trust myself more from when I was home alone writing and spent a lot of concentrated time on it than I trust myself on the set with changes, or [suggestions from] other people who are visiting for the day. I’m not a big fan of improvising and changing things the day of. Sometimes it does sound funny and fresh, but in general it’s a great idea to stick to the script.

Q: I do see the influence of the screwball comedies in your movies, especially in What Women Want.

A: Well, Helen [Hunt] and Mel [Gibson] were sparring co-workers, which was something you saw a lot in the Tracy-Hepburn movies, and the obvious ones, like His Girl Friday. In a lot of those movies, the workplace was, in a way, a sexy environment. In His Girl Friday, when they’re working on a story together, to me, it was very romantic. Just the way he watched her work, you knew there was no other woman for him. And those Barbara Stanwyck movies, where women were so dynamic at work. As a younger person I fell in love with that kind of storytelling. Now, it seems that many of the women who are great at their work are destined to be unhappy. Back then it was presented as if they were these fantastic, fabulous, loveable women.

Q: Back to the physical comedy, there’s a scene in Something’s Gotta Give where Jack Nicholson is in the hospital and he comes out in front of the women and the back of his gown is open, which they find very funny; then Diane Keaton tries to calm him down and they end up waltzing.

A: They just did that. That’s the great thing about having Diane Keaton and Jack Nicholson. You write a scenario and they take it to the next level. They just knew what to do and how to do it. And then he had her in his arms. It got them to hold each other in an unexpected way.

Q: The sequence in that movie that probably gets the most attention is the one where she sits down to work on her play after Jack Nicholson breaks her heart, and she’s sobbing and then laughing, bursting into tears and then cracking herself up.

A: We had a lot of fun doing that. It was an exaggerated, honest scene. Comedy—you can’t make it completely real or it becomes drama—so I try to accelerate and intensify it. So when this guy screws with her and messes her up, the bonus is that she’s on fire as a writer, because she has the key to what she’s writing now, which is her own emotional truth. So I loved that beat where she’s letting it all out and then every once in a while she writes something really funny so she laughs. We kept doing that beat over and over. We shot it in the kitchen, the bedroom, the beach, in the shower. We kept grabbing these little shots for months. Whenever Jack wasn’t there, we’d say, ‘Let’s do it here! Let’s do it here!’ So it was really fun. It took a long time to do, but it cut together really well.

Q: Do you think there are any rules when it comes to directing?

A: Everybody breaks the rules visually. I’ve always made movies in a sort of classic form, the way people have done it for a long time. But it seems that now more than ever a lot of people are breaking those rules. I think that visually, movies are in a great place. I really like watching a lot of the films that are out now for the visual style, I find it really exciting.

Q: Any examples?

A: Any Ridley Scott movie. He does so many setups, and he’s constantly moving the camera just enough so that it’s a different kind of shot. I find his movies are great learning tools. ‘Oh look, he’s over there now, and the eye line isn’t exactly right…’ I’ve also been watching Wong Kar Wai’s My Blueberry Nights. And you know, absolutely no rules. For me, a more conventional thinker, that really opens me up. I love watching his movies; I find them educational. Storytelling always matters, I think, because if you don’t have that, you’re in trouble, but how to visually tell the story…the rules don’t really matter. Not that anyone is going to think I’m making a Wong Kar Wai movie.

Q: When you watch these movies, is there something you’re paying special attention to?

A: It’s good to watch with the sound off, because once you’re following the story you’re not really watching the shots. And I print stills from movies sometimes. I did watch The Graduate for this movie. Mike Nichols is such a good visual director and the staging on that is wonderful. He’s just such a master.

Q: Your choice of music is always interesting. Can you talk about how you use it?

A: Sometimes when I’m writing I’ll play Cole Porter, just because the rhythms and the lyrics are so perfect that it’s like having a smart partner in the room. I have a huge collection of music that I listen to when I’m writing, and I also prepare a lot of music before I start directing. I put it all onto an iPod that I have with me on the set. It’s helpful to the actors, because for an emotional scene, I’ll play it and say, this is how it feels, to keep us in the zone. I mean, there’s going to be music there anyway, they might as well benefit from it. I think the actors like it, too. Almost every movie I’ve done, they look at me like I’m the deejay, and they request certain songs for certain scenes. On this movie, I had already sent Steve and Meryl and Alec a CD of all the songs I was listening to while I was writing, just so they could get there with me.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT: Meyers (right) stages a dinner with Keanu Reeves,

FOOD FOR THOUGHT: Meyers (right) stages a dinner with Keanu Reeves,

Frances McDormand and Diane Keaton in Something's Gotta Give.

(Photo Credit: Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.)

Q: What kind of music is it?

A: It’s all over the map. Fred Astaire and Weezer, they’re both on there.

Q: Your editor on this movie is Joe Hutshing, who also did Something’s Gotta Give and The Holiday. What’s that stage of the process like for you?

A: It’s so important. I love working with Joe. We have a really safe relationship in the cutting room. We’re allowed to try things, and really have fun. In terms of enjoyment and the part of your brain you use, it’s probably the closest thing to writing. You’re in a dark room all day; you have the quiet and the peace of mind of writing. And it’s fun because now you have all the pieces there.

Q: What about editing in terms of creating comedy?

A: Well, you can’t make it happen in editing, but if it’s there, you can make it happen really well.

Q: To what extent do you use previews as part of your process?

A: You might have a good sense of where you are, but after previews, you have a definitive sense of where you are. I actually like reading the cards. If there’s a problem, you find out. For the most part, previews have gone well for me and they’ve helped me get the film in better shape. Anyway, you don’t have a choice. [laughs]

Q: Do you think that the female audience is given short shrift, in terms of the movies that get greenlit for production?

A: I think they are, actually. I don’t think there’s enough interest in movies about women. The ones that get made, the dramatic ones, tend to be depressing. There’s not a huge variety of fare for women. There are romantic comedies, which become very repetitive, and they’re mostly limited to a certain age, with the same people in them. But I don’t think the audience in general is that well served. Everything is of a genre now.

Q: Do you think this emphasis on the male audience at the studios affects your ability to get a movie made?

A: Actually, I think one of the reasons I’ve had the opportunities I’ve had is that I’m bringing them something different. I suppose that’s what it is. But I don’t really know how to talk about that.

Q: You’re on your fifth movie since you started directing a dozen years ago. Are you happy with that pace?

A: Oh yeah, that’s me. I couldn’t do it any more often. You know, what it’s like now, right on the heels of finishing a movie, you’re out promoting it. You go to Europe, you go to Japan. After that there’s a couple of months of just catching up with life, with sleeping and eating balanced meals. You’re sort of reintegrating. Since I’ve been directing, I take a full year off. Then I write, and that takes close to a year. Then there’s the six months of getting it together and prepping. So I make a movie about every three years. I don’t think I could go any faster. I read about someone who is cutting a movie and prepping the next one at the same time. I literally cannot understand how you could do that. Where would the hours be? How do you have any space left in your head? I mean, it’s ‘memory full,’ isn’t it?

Q: What have you learned that you wished you’d known when you started out as a director?

A: That question really goes two ways. I think the reason many people make really good first movies is because you don’t know a whole lot. In some ways, that naiveté becomes bravery. The more you know, the more you see the pitfalls, and you start to think two steps ahead. On the other hand, I have much more confidence now, and a better understanding of all things involved in directing. So I don’t know if the films will be better, but certain aspects of them will be better, because I’ve learned. And I get a new kind of bravery.

Q: What about working with actors, how has that changed?

A: I’ve been so lucky to work with some of the actors I’ve worked with, and you learn about directing from them. They’re all different, they all have a different technique, a different way of getting there. You learn how to express yourself with them. With some actors, two words does it. With others, it’s a long conversation. With some, it’s being flirtatious, or being a girlfriend to the girls. Your tool kit grows.

Q: Would you say that as a filmmaker, the work with the actors is your biggest focus?

A: It will be the day we start. I mean, I have been directing this film for the last three months, because I’ve been prepping it, and it has some size to it. So I’ve been directing a big group of people to get us all to the starting gate. But what I’m looking forward to now is working with the actors. Because you know, storyboards don’t talk. Clothes don’t walk. The sets aren’t funny or emotional. So now I really get to do the thing that was in my mind when I sat down to write. And I like these three leads so much. So when that moment comes—when they’re in their clothes, in their makeup, on the set, being called by the name of their characters—that’s when the real fun begins.