BY JEFFREY RESSNER

BATTLEGROUND: Bigelow shot The Hurt Locker in Jordan, sometimes in

BATTLEGROUND: Bigelow shot The Hurt Locker in Jordan, sometimes in

110-degree heat. "I'm interested in extraordinary situations, in heightened

reality," she says. (Photo Credits: Summit Entertainment)Kathryn Bigelow's home, a slate-gray minimalist house with bold, open spaces, is tucked away down a quiet lane off a busy Beverly Hills canyon. The only sound is the wind rustling through the eucalyptus trees and not much else. Bigelow's peaceful and reclusive surroundings, however, seem at odds with her hyper-energized approach to cinema.

Bigelow feeds off the rush of adrenaline. She talks enthusiastically about movies and relishes the physical act of filmmaking. And just mention cave climbing, skydiving, or any other type of crazy, dangerous act and her eyes widen, she perks up, she's totally there. Even making coffee in her utilitarian kitchen, Bigelow laughs as she recalls the near-nuclear, 130-degree heat at the Middle Eastern location for her forthcoming war thriller The Hurt Locker. She isn't the type to kick back and relax.

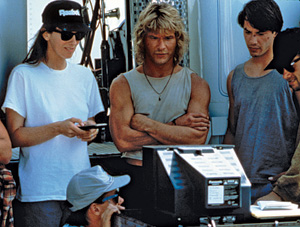

Consider her body of work: For Point Break (1991), she was right there in the airplane, parachute on, filming Patrick Swayze as he flung himself into the sky. During surfing scenes in the same film, she would paddle on top of the crashing waves on a longboard or lean over from a nearby boat, hovering as close as possible to Keanu Reeves without getting in the shot. For the opening of Strange Days (1995), a film conceived by her then-husband James Cameron, she commandeered a massive crane that dropped a cameraman over the precipice of a tall building. But her films are more than simply big explosive moments punctuated by brief periods of calm. "Peak experience only exists in relation to something that is not," she once told a film magazine, so those deceptively restful scenes in her films are merely less intense as opposed to very intense.

Bigelow is by training an artist, and her love of canvas, clay and other mediums formed her worldview long before she shot a single foot of celluloid. Stacked on her coffee table alongside a few scripts are books by Rem Koolhaas and Raymond Pettibon, and in another room hangs a striking black-and-white photograph by her former neighbor in New York, Robert Mapplethorpe. She spent her teenage years painting at the San Francisco Art Institute and later at the Whitney Museum studying under Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Sontag. She values her serious art background, and credits that part of her life with keeping her as aware as possible and, perhaps, saving her from making frivolous films. "Coming from the art world, there's a kind of gravitas that can be very motivating. I carry that with me into films—not necessarily seriousness, but an opportunity to be as probing and penetrating with material as possible. I don't make choices in a cavalier way. I find stories that genuinely move me and then make the hopefully logical assumption it will move others."

As a director, Bigelow refuses to stay stuck in any single style. Her first theatrical film, The Loveless (1982), was a post-postmodern biker flick inspired by Kenneth Anger followed by a vampire Western Near Dark (1987) and the surf heist picture Point Break. Switching gears again, she made the feminist police thriller Blue Steel (1990), the claustrophobic Soviet submarine story K-19: The Widowmaker (2002), and now The Hurt Locker. Bigelow's genre-jumping is tied together by the velocity levels she reaches on screen. All her films are punctuated by innovative foot and vehicle pursuits, complex law and order tangles, as well as occasional pummeling wallops to the gut. She'll often mix different camera styles—tracking, handheld, Steadicam—and even create special lightweight hardware to film her chase scenes, such as the robbery getaway through suburban backyards in Point Break.

Bigelow has a simple explanation for how she films these scenes: "It's instinct!" she says. Furthermore, she feels that categorizing her work as "action movies" just doesn't do justice to what she does.

"'Action' is a label for video store owners," she says bluntly. "I guess if I had to single out a theme for what I've been up to, I'd say it's some sort of journey to explore film's potential to be kinetic," she says. "This probably started unconsciously, but it's there in one way or another in all my movies. I'm always trying to squeeze the most energy out of the frame."

Her term "kinetic" seems to apply, whether she's telling an interior story like the suspense-filled drama The Weight of Water (2000) or, perhaps most precisely, The Hurt Locker, which explores the death-defying work of bomb disposal technicians who face doom and gloom amid daily explosions on the ground in Iraq. Like a Hitchcock thriller in which viewers teeter on the edge of their seat, gnawing their fingernails as they wait for a bomb to detonate (or not), The Hurt Locker demonstrates that nothing beats smart editing for creating a heart-pounding special effect.

"You can deploy kinetics to create many effects: suspense, tension, fear, erotic desire, confusion, happiness—basically any heightened emotional state," she says. "What it's not very good at is showing boredom and stasis and ordinary life. [But] ordinary life doesn't interest me as much. I'm interested in extraordinary situations, in heightened reality."

Bigelow directs Jamie Lee Curtis in Blue Steel.

Bigelow directs Jamie Lee Curtis in Blue Steel. With Ralph Fiennes on Strange Days.

With Ralph Fiennes on Strange Days. Bigelow checks the monitor with Patrick Swayze on Point Break.

Bigelow checks the monitor with Patrick Swayze on Point Break.

(Photo Credits (top to bottom): Photofest/Corbis/Everett)For The Hurt Locker, Bigelow starts out by showing the potential blast radius with long shots and overhead views, gets closer to the ordinance itself and finally zeroes in with close-ups on the fingers of the technician defusing the lethal devices. "The subject is so rich, you don't need to interfere or embellish," she says. "The devastating potentiality is what permeates every frame."

She first started experimenting with the kinetic style on her second picture, Near Dark. "I knew I didn't want to use static composition with fixed cameras," she says, which led her to shoot the genre-melding Western-horror film with mostly handhelds.

By the time she made The Hurt Locker, she was running as many as four handheld Super 16s simultaneously. Among other advantages, this immersive technique offers the opportunity to look at the same sequence from various vantage points in the editing room. After all, running through an entire scene from start to finish without breaking it down into individual shots can bring a verisimilitude that's difficult to capture any other way.

"Everyone is in motion and it's a constantly moving instrument," she says of her hydra-headed camera crew. Some actors need time to grow accustomed to the style, she concedes, but they soon adapt because the quad squad allows them to truly stay in character without "playing to the camera." On the other hand, Bigelow came home from location in Amman, Jordan with nearly 200 hours of material, "an exponentially complicated body of raw data in the cutting room, and a mountain of footage." The shooting ratio was about 100:1 (The average is about 20:1).

Her work was slightly easier to manage because, early in the process, she relies on elaborate storyboards to map things out, no surprise given her artistic background. "They're the visual first draft," she says of the formative sketches used "to shape the visual grammar of the movie." On the set and afterwards, however, she rarely refers back to them. By that point, she's already fully absorbed their content and likes to keep an open mind for the inevitable new ideas that will pop up. "You just can't anticipate all the spatial nuances at the storyboard level," she notes.

The same goes for improvising action or ad-libbing dialogue. "The movie has to reinvent itself on locations," she says. "This gives you a feeling of seamless authenticity. Rather than it seeming like the actors and drama are sandwiched in a particular space, the place, the action, the dialogue, and the shooting style all seem to be one organic whole... You want to anticipate it all, but there is always a wonderful surprise."

One such surprise on Hurt Locker occurred in a key early sequence that introduces the macho new bomb tech Staff Sgt. William James (Jeremy Renner). The modern military cowboy is disarming a car rigged with explosives that's parked outside of a U.N. building in Baghdad. "We rewrote the script and the logistics to fit the architecture of the building and all its various vantage points," says Bigelow. "In the original conception, all the action took place at street level. But when we got to the location and saw that it had four tiers—the street, the roof, a balcony and a nearby mosque—the scene was redesigned to take advantage of the different levels."

Indeed, Bigelow found the Middle East's urban landscape and vast arid desert on The Hurt Locker a welcome change from the controlled, claustrophobic studio sets of K-19: The Widowmaker (2002). The submarine, she recalls, confined her to such a small space, she had to strategize different ways to keep the energy moving from scene to scene. And, because the compartments on subs are all fairly similar, she was forced to find novel ways to block and shoot.

"Overall," she says, "it was very exhilarating to go from the confinement of the submarine to the wide open chaos of a war zone. It felt like someone had given me a much bigger brush to paint with."

Shooting in Jordan, Bigelow worked closely with King Abdullah II's Royal Film Commission on setting up a trainee program for young filmmakers. "In every department, even the ADs, we had one or two trainees," she recalls. "Nothing like that had ever taken place in Jordan and so it really became a collaborative, extremely beneficial experience."

There were some cultural surprises along the way, too. "The end of our shoot took place during the two weeks of Ramadan, and that was wonderful. You have to break at sunset because, all of a sudden, you'll look up, and half your crew is gone. But, after the first day, I was able to anticipate that and work it into the shooting schedule."

Bigelow often works like a journalist when putting together her films, researching the subject, conducting background interviews, visiting as many of the territories as possible. With The Weight of Water, a film that involves the murder of Norwegian immigrants, she delved into her own family's heritage. "My mother's side all came from Norway," she says, "and there were many rich stories about their arduous journeys and the difficulties in transplanting themselves. So the film gave me an opportunity to examine that."

DP Jeff Cronenweth, Bigelow and 1st AD Steve Danton in the Arctic

DP Jeff Cronenweth, Bigelow and 1st AD Steve Danton in the Arctic

on K-19: The Widowmaker (Photo Credit: George Kraychyk)Bigelow gives her performers homework as well. "I encourage actors to be participatory in the process," she says. For Point Break, she placed Reeves with a real-life FBI agent for training; on The Hurt Locker, the actors went to Fort Irwin in California's Mojave Desert to engage in training, and in Kuwait learned how to defuse bombs from explosives experts. She'll demand rewrites, add in new material, do whatever it takes to get as close to reality as possible.

"You have to be intimate with the material, work with it from the DNA out so that there's nothing you haven't anticipated," she says of her attention to detail. "It gives you confidence to work with the actors and the crew if you're all totally immersed in the story's environment."

Bigelow feels her various stints directing television dramas (Karen Sisco, the miniseries Wild Palms, Homicide: Life on the Street) provided her with yet another valuable skill: time management.

"My TV work, especially Homicide, completely broke my fear of schedule," she says. "You're doing 10, 12, 13 pages per day with this much time and there's no latitude whatsoever. Up until that point, I was always anxious about making sure that I had enough time and resources for my work. After that, nothing seemed as important as story and character, and everything else became just mechanical procedure."

With eight features under her belt, Bigelow is getting some of the best reviews of her career on the festival circuit for The Hurt Locker, which opens in the spring. Unlike the other Iraq-themed films over the past two years that failed at the box office, most of them about returning GIs, her new movie deals with realistic boots-on-the-ground tension. It's not an Iraq war movie, per se, it's a straight-ahead war movie and, above all, it's a movie lover's movie. "This is a combat film, and there were no others like it," she says. "I was also a producer on the project, so I made sure we kept it very contained and on a budget that was very workable."

More than anything, Bigelow recognizes she accomplished some important professional breakthroughs with this film. "By the time I did

Hurt Locker, the sort of craft questions that concerned me as a younger filmmaker were no longer as pressing," she admits. "I've come to the point where I feel pretty confident about my ability to execute, so the artistic questions revolve around substance and material and what kind of story I want to tell. The question I ask myself before a new project is: 'Is this really a film I want to spend my life making?' That's partly what drew me to

Hurt Locker: a desire to make topical, relevant films that comment on the American condition."