BY GARY GIDDINS

Hitchcock with Kim Novak on Vertigo. (Credit: Everett Collection)

Hitchcock with Kim Novak on Vertigo. (Credit: Everett Collection)

Alfred Hitchcock has had the last laugh—a long, posthumous howl. Biographers and critics gnaw at his personal peccadilloes and professional limitations, yet he remains the most durably popular studio-era film director in the English-speaking world. Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton require a fondness for silence; John Ford for Irish knockabout; Orson Welles for operatic amplification; Ernst Lubitsch for continental manners; Howard Hawks for masculine codes; and John Huston for bemused pessimism. But Hitchcock—cold, sharp, irreverent, gripping, rarely poignant (his audience has no fear of ever tearing up)—continues to draw crowds across the board, generation after generation. His films have achieved something better than timelessness; the older they get, the more astutely they function as social critiques. They may be frostily schematic, but long after we know who did what to whom, we return repeatedly for the nuance, the humor, the stylishness, the daring, the frisson.

Consequently, most Hitchcock films have long been available on DVD. But a few recent releases up the ante, the packaging indicating that these are classics—in the way books and music become classics, to be stored on the shelves of all civilized homes. Universal has issued authoritative two-disc editions of Rear Window, Vertigo, and Psycho, complete with feature-length documentaries, various supplements, and one Hitchcock-directed episode each from his television series. At the same time, MGM has produced an enlightening eight-film, loose-leaf folder called Alfred Hitchcock Premiere Collection. It includes three neglected films from his English period in stunning new restorations, and five from his first decade in the United States, all but one reflecting his uneasy yet fruitful collaboration with David O. Selznick.

(Credit: Universal NBC)

(Credit: Universal NBC)

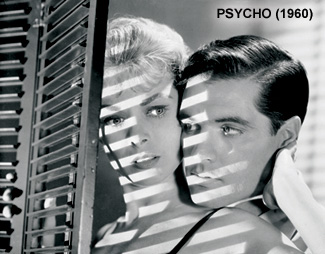

If you weren't around in 1960, the degree to which Psycho changed filmmaking and film-going may be hard to fathom. This was his low-budget picture, a return to black and white after the luminous color of the audacious, commercially unsuccessful Vertigo (1958) and the inevitable return to his most reliable plot device, the innocent man on the run with woman of uncertain loyalty, of North by Northwest (1959). He shot Psycho with efficient techniques learned from television, and advertised it with a showman's bravado: No one would be admitted after the picture began. Hitchcock couldn't actually enforce a policy of restricted entry, but as word of mouth spread, audiences were willing to adjust the habits of a lifetime and line up at the appointed hour.

Psycho not only made people mind the clock, but also hastened the death of the double bill. When the film ended, your much-assaulted brain demanded light. On the other hand, you didn't want instant light. Hitchcock recognized he couldn't send shaken customers home immediately after the mental/physical seizure of Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins in an inspired, career-killing performance: He could never again play a normal guy). The audience needed a few minutes to catch its breath, and in those days, movies didn't end with six-minute credit rolls. So he added the sequence in which a comically adrenalized psychologist explains things the audience already understood, but appreciated having spelled out all the same. Maybe Hitchcock had a secondary motive as well: The shrink augurs the numberless critics who have long since explicated every gaze, gesture, and prop in his films.

Guilt is the central theme running through all of Hitchcock's work, and there is plenty to go around. Yet with Psycho, Hitchcock stepped beyond the typical gambit of making the audience associatively guilty by manipulating it to, say, root for violence or relish sexual indiscretion. He went for the jugular, exploiting his own voyeuristic obsessions, showing intimacies no one expected to see in a Hollywood movie: from Janet Leigh's brassiere (shot so close you can almost feel the texture) to the whirlpool of a flushing toilet, not to mention two relentless stabbings. At the moment Leigh's character is assaulted, we have been caught ogling her in the shower.

Credit: NBC Universal)

Credit: NBC Universal)

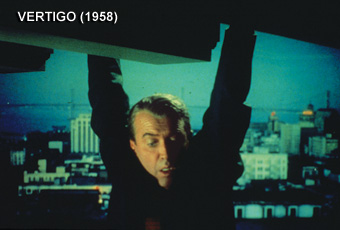

In Rear Window (1954), James Stewart plays a hobbled photographer who spends the entire film staring at his neighbors through his window, eventually happening upon a murder—a discovery so entwined with wishful thinking (what's the point of voyeurism if you don't see something you shouldn't?) that he seems to have all but willed the crime. In Vertigo, Stewart is a hobbled detective who, after being hired to stalk a woman, takes up stalking as his fulltime occupation, turning one woman into another and watching as each tumbles to her death. Rear Window, with Grace Kelly providing languorous glamour, was a hit; Vertigo was a debacle. Small wonder. Its circuitous storyline and open-ended structure could induce, well, vertigo.

Yet Vertigo is now widely regarded as Hitchcock's masterpiece, and a frequent candidate for best-ever shortlists. Gorgeously photographed by Robert Burks and scored by Bernard Herrmann, fastidiously art-directed by Henry Bumstead and Hal Pereira, and flawlessly acted, not least by the mannequin-like Kim Novak, it is Hitchcock's most ravishing and uncharacteristically emotional film. It was also his first attempt to regulate audiences. The ads vainly pleaded, "You should see it from the beginning!" If you didn't, you were completely clueless, but even seen properly, it was judged by many to be incomprehensible—so much so that the censors apparently failed to notice that the murderer gets away scot-free. (Stewart's character is nicknamed Scottie.) Hitchcock also introduced his brassiere fetish in Vertigo: Scottie's ex-flame, played by the maternally purring Barbara Bel Geddes, designs bras for a living.

To facilitate the film's extravagant romance, dreamlike tempo, convoluted plot, burning fixation, and lethal impotence, Hitchcock sets up the story with a gambit popularized by an Ambrose Bierce story, An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, in which a hanged man fantasizes his escape in the seconds before the rope breaks his neck. Scottie and a patrolman chase a thief over rooftops; the cop falls to his death and Scottie is left hanging onto a gutter with bare fingers. Hitchcock's scrupulous editing shows there is no way he can survive. Yet in the next shot, he seems to have suffered no more than a sprain. The rest of the film plays out like the fantasy of a man falling into the void. It ends with him literally hovering over that void.

(Credit: NBC Universal)

(Credit: NBC Universal)

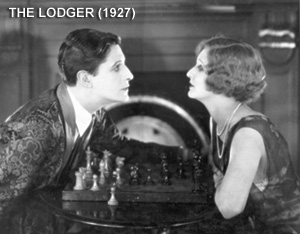

Plunging from great heights is frequently the fate of Hitchcock villains. But the void represents something else—a limbo between salvation and hell. In the climactic episode of Hitchcock's first signature film, The Lodger, a 1927 silent that opens the MGM binder, the eponymous lodger, suspected of being Jack the Ripper, hangs manacled from a fence, with a furious mob on one side and police on the other. Having cast matinee idol Ivor Novello in the lead role, Hitchcock was obliged to revise Marie Belloc Lowndes' 1913 novel and make him innocent. Even so, the lodger gets more than a whiff of brimstone, saved by sheer luck from becoming a vigilante killer on the trail of the real Ripper.

Sabotage (1936) has plenty to recommend it, especially in MGM's sharp transfer, including a set piece in an aquarium and amusingly judicious glimpses of Soho life. But it remains Hitchcock's most unpleasant failure, owing to an unforgivably sadistic sequence in which a young boy is blown up. Rather than have the event reported after the fact, as in Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent, the novel Sabotage is based on, Hitchcock follows the boy for 10 minutes, encouraging our identification with him, and then cuts from the explosion to a cinema where the audience is laughing at Disney's Who Killed Cock Robin? to the boy's pet canaries. It's an instance of "wit" so misplaced as to verge on what Francois Truffaut called (in his book-length interview with Hitchcock, excerpted on the disc as an audio extra) cinematic malpractice.

Hitchcock recognized his error, and followed it with one of his most enchanting and underappreciated movies, Young and Innocent (1937) in which an innocent man on the run is aided by the chief constable's teenage daughter (Nova Pilbeam). Several unmistakable harbingers of later Hitchcock films—not least an ominous shot of massed seagulls—and edgily satirical characterizations, including an inept lawyer out of Dickens, almost allow us to overlook one of the biggest plot holes in any crime film. A woman of dubious morality has been killed and the police never even question her batty husband, an incompetent jazz drummer with a mean twitch. They are too engrossed with the purely circumstantial evidence pointing to the hero. Hitchcock's long, climactic crane shot, closing in on the telltale twitch, is as deliriously satisfying now as it was 70-plus years ago.

Inevitably, Hollywood lured Hitchcock, a transition engineered by Selznick, whose intrusiveness, habit of adding shots in postproduction, and conventional editing drove Hitchcock nuts. On the other hand, his story sense was undoubtedly helpful, and played a decisive role in the success of Rebecca (1940, Selznick's second consecutive best-picture Oscar after Gone With the Wind); Spellbound (1945); and the incomparable Notorious (1946), though Selznick's involvement was uncredited and limited. Notorious, with Cary Grant as an unpleasant American agent, Claude Rains as a weirdly sympathetic Nazi apparatchik, and the luminous, never-more-heartbreaking Ingrid Bergman as the former party girl caught between them, is perhaps Hitchcock's most complex and rewarding romance in the years preceding Vertigo. The plot makes little sense, yet there is so much going on, you don't care—no matter how many times you see it.

But Selznick's interference took its toll with The Paradine Case (1947), the stylish but unfocused British courtroom drama hoisted on the petard of a miscast Gregory Peck, whose character, an allegedly brilliant attorney, is unreasonably obtuse. Hitchcock had his last word on Selznick in North by Northwest, adding the middle initial "O" to Cary Grant's Roger Thornhill, creating the monogram ROT.

The eighth film in the MGM collection, made on a loan-out to Fox in 1944, is the often ignored Lifeboat. The disc restores Glen MacWilliams' sensuous photography, accentuating the resourcefulness of Hitchcock's camera placements and rhythmic cutting in this tour de force that was staged entirely in a lifeboat in a studio tank. If the patriotic pep talk, as enunciated by Tallulah Bankhead and Henry Hull, rivals in the realm of throaty self-importance, dates the story, the masterly control of the material and meticulous development of the manipulative Nazi (played by Walter Slezak) is riveting. Even Hitchcock's wartime propaganda survives to engross another day. Guilt springs eternal.