BY LYNDON STAMBLER

CALLING THE SHOTS: Drew Esocoff (center) shows some emotion directing

CALLING THE SHOTS: Drew Esocoff (center) shows some emotion directing

America's dramatic victory in the men's 4x100 swimming relay.

(Credit: Craig Schiller/NBC)

As the Beijing Olympics approached in August, NBC's directors were on edge. After all, Steven Spielberg, citing China's relationship with Darfur, had resigned as an artistic consultant; the May earthquake in Sichuan Province had killed more than 70,000 people and devastated the country; Parisians had assaulted Olympic torch runners; China had cracked down on Tibetans and spiritual groups like the Falun Gong. And just before the Games, Muslim extremists had attacked western China.

But as soon as the Games began, tensions seemed to ease. "This past year it was one thing after another, whether it was a natural disaster or political turmoil," said Bucky Gunts, head of production for the NBC Olympics and director of the opening ceremony, shortly after the Games started. "But things have calmed down. The opening set the tone. We can concentrate on covering the Olympics."

From Michael Phelps winning eight golds to Nastia Liukin and Shawn Johnson finishing gold and silver in the gymnastics all-around competition to Jamaican sprinter Usain "Lightning" Bolt's three world records, the directors went beyond documenting the action. They selected the images that told the dramatic stories to 214 million U.S. viewers, making the Olympics the most-watched event in U.S. television history.

"I was watching on TV too, but I was watching on a lot more than you," jokes NBC gymnastics director David Michaels, who surveyed the live action on 64 monitors from a portable control room.

NBC Sports Chairman Dick Ebersol approached Beijing Olympic organizers in 2005 about holding swimming and gymnastics events in the morning so the events could be aired live during primetime in most of the country. Gunts, responsible for the overall look of NBC's coverage, took 15 trips to Beijing to identify camera placements. At times he was accompanied by the directors of gymnastics, track and field, swimming, diving and beach volleyball. For other sports, NBC used the world feed available to all countries.

As NBC's opening ceremony director, Gunts met often with film director Zhang Yimou, who was helming the spectacular curtain-raiser. Yimou used storyboards to explain the significance of his $100 million creation to Gunts, who plotted his coverage to hit specific moments, from human formations in the Bird's Nest arena to fireworks above the city. But Gunts also improvised. "I was on edge the whole time," he says, even after covering every Olympics since 1988. "It was by far the best ceremony I've ever seen. I wanted to make sure I shot wide rather than tight to show how many people were in the cast."

The ceremony began with 2,008 silver-robed drummers moving kaleidoscopically. "I tried to fill up every pixel of every screen with action and people." Later, for the undulating printing cubes that turned out to be human-operated, Gunts sought a middle shot so viewers could see the wavy motion. For the swift-moving, florescent tai chi dancers, the cameramen shot low to capture their speed, and high to show the concentric formations.

Gunts had access to 45 world-feed cameras and also relied on 23 NBC cameras spread around the Bird's Nest, three outside the stadium (in a helicopter, a roving camera on the ground, and a robotic atop a tower in the Olympic Green) for aerials and the fireworks. NBC cameras were also trained on hosts Bob Costas, Matt Lauer and other announcers in the stadium. One remote camera caught President Bush conferring with Vladimir Putin just after Russia invaded Georgia, something Costas later questioned Bush about.

(Credit: Mike Hewitt/Getty Images)

(Credit: Mike Hewitt/Getty Images)

There were controversial moments, including a girl who lip-synched the anthem, "Ode to the Motherland." China also provided computer-generated reproductions of the fireworks "steps" that were set off across Beijing to symbolize the 29 Olympiads. NBC made it clear that the footage it was showing was computer-generated. "I have no problem with what we did," Gunts says. "As far as I know, the fireworks were happening but you couldn't capture them live the way [the host did with] computer graphics."

Gunts believes the ceremony will prove historic. "We haven't seen pictures like this coming out of China before," he says.

Before traveling to China's "coming-out party," all the directors went through an online tutorial and attended a two-day seminar on what to expect. The message: Be respectful. Gunts, Michaels, swimming director Drew Esocoff and track and field director Andy Rosenberg praised China's handling of the Games.

"Beijing was fantastic," Michaels says. "I'm not talking about human rights. The city was amazing. The people were incredibly friendly. When they took half the cars off the road, there was no traffic. I've never seen a city so decked out in Olympics stuff."

And NBC was able to translate that excitement into unprecedented ratings. "Anybody who says the ratings were great and Michael Phelps had nothing to do with it is crazy," says Esocoff. "We were going to make sure that anything he did we had and I think we were there 100 percent of the time."

Perhaps the defining moment of the Olympics came on day two of the competition during the 400-meter freestyle relay, when U.S. swimmer Jason Lezak tracked down France's Alain Bernard, who boasted they would "smash" the Americans. The U.S. won by 0.08 of a second, keeping Phelps' eight gold medal quest alive.

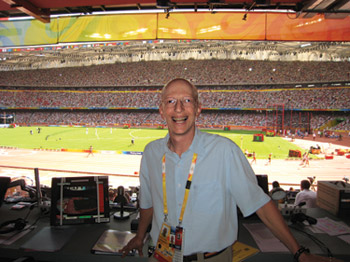

IN THE BEGINNING: Bucky Gunts, who has directed every Olympics since

IN THE BEGINNING: Bucky Gunts, who has directed every Olympics since

1988, said this was by far the best opening ceremony he's seen. (Credit: NBC)

"While this was unfolding, I see the shot of Phelps going crazy on the deck and Lezak in the pool," Esocoff says. "I could see the French being disappointed in a couple of other cameras. It's a controlled kind of mayhem. You know there is going to be great emotion. His mother and coach are going crazy. His parents are divorced, so you understand the bond between Michael and his family is extraordinary. Every bit of emotion on her face is natural."

Esocoff had confidence in the world-feed underwater cameras and the basic race coverage—the start, the tracking, and the turn cameras. But he employed eight NBC cameras, including three cameras at the turn end of the pool for reactions of swimmers on the opposite deck and in the water; one at the start/finish line; and two handhelds and hard cameras for isolation shots of Debbie Phelps, coach Bob Bowman and the swimmers. Viewers were riveted as Phelps and teammate Garrett Webber-Gale puffed out their chests and screamed. But Esocoff wanted both sides of the story. He credits his disciplined camera crew with getting the dejection of the French swimmers on the deck and of Bernard with his head down against the side of the pool. "People aren't going to remember those shots as much as they remember the shots of the U.S. team going crazy, but to me they were equally as important. They're split-second reactions."

For the 100-meter butterfly, in which Phelps beat Serbia's Milorad Cavic by 0.01 of a second, Esocoff had to wait a split second until the virtual lane graphics, triggered by electronic touch pads, showed that Phelps won. "To the naked eye it was too close to call," Esocoff says. The isolated cameras caught reactions from Phelps' mother (her eyes bugged out in disbelief), his coach, and a disappointed Cavic. Phelps splashed the water and shook his head as he saw the margin of victory.

"You don't want to overcut this," Esocoff adds. "It's a head-to-head battle so there are really only two key shots in the pool that you want: Phelps and Cavic. You don't want to cut them off before it's necessary. You can get into a situation directing sports where there's so much eye candy on the monitor wall that you want to get everything on in two seconds. You don't have to do that."

After Phelps had won several golds, Esocoff deployed an animated sequence created by the graphics team that showed why Phelps' body is perfect for swimming. "You don't want to clutter this stuff," he says. "When you have a live Olympics it's nice to stay in the moment."

Finally, after Phelps won his eighth gold, Esocoff accompanied him to the International Broadcasting Center to replay the races for him. Phelps revealed another prodigious talent. "He was devouring as much food as he could get into his body in 45 minutes. He was wearing his baseball cap backward, unaffected by the whole thing."

Esocoff, who directs NBC Sunday Night Football, had never covered the Olympics before, but he was there when one of the greatest dramas in Olympic history unfolded. "We'll probably never have another week like that in our lives," he says with a deep exhale.

David Michaels, who has directed Olympics gymnastics since 2000, says covering gymnastics is more intense than a race or a game. "In gymnastics, you're trying to tell the story with pictures of what it's like to be standing up there and what happens when it finishes. We need to have the shot of them chalking up, the close-up of them taking the deep breath before they go, the dismount, and the hug for the coach. There are a million moving parts. There are four games going on simultaneously and games within the games."

(Credit: Julian Finney/Getty Images)

(Credit: Julian Finney/Getty Images)

PERFECT 10: David Michaels (white shorts above) and his crew

prepared for the gymnastics showdown between Nastia

Liukin (top) and Shawn Johnson by doing tai chi.

When Nastia Liukin and Shawn Johnson competed head-to-head in the all-around competition, NBC, which had 135 people working at the National Indoor Stadium, presented the floor exercises live and commercial-free. "It's unfolding in this way that nobody anticipated," Michaels says. "All the marbles are at stake and no commercials. My cameramen are hitting on all cylinders. It's perfect. We've got five guys on the floor and for most of them it's their third Olympics. There's a lot of unspoken stuff here. Obviously, there's a battle plan going in, but it's the cameramen knowing what to do. I'm moving them around as well. It's all of us working together to make sure we have all the shots."

There is no take two in live TV, says Michaels. That's why the NBC cameramen, who wore green vests to distinguish them from the blue-vested world-feed cameramen, were so important. NBC had five handhelds on the floor, five hard cameras around the arena, one gib and a robotic "beauty camera" in the rafters. The cameramen served up an array of close-ups and wide shots.

They have covered Liukin and Johnson for years. When Liukin came on the floor that morning, she greeted cameraman Ken Woo: "Great to see you. Finally, a familiar face."

"If they were going to cry or whatever they were going to do, they weren't going to do it in front of a guy in a blue vest," Michaels says. "I know if Liukin is performing there's going to be a camera on her dad, one on her mom, and one on whoever is watching her that's maybe in second place, looking for her to falter."

Johnson was the last to go. Michaels told his cameramen that she still had a chance to win if she got a great score. "I'm letting the drama unfold, but I'm telling a story by which shots I choose," he says. "It's having all the shots, not just a single shot of 'Okay, here's Shawn Johnson and she's ready to go.' It's what is Nastia Liukin doing? Is she watching or not watching? Is her father watching or not watching? Is her coach cheering or standing there stoically?"

Michaels' spotters located important people in the stands, like gold medalist Mary Lou Retton. "If Shawn wins then she would become the next Mary Lou," Michaels says. "So before she goes, I'll say, 'Camera Three give me that shot of Retton.' I'll have that isolated. As you move on to each routine, you reset which cameras are isolating on which people."

The cameras delivered Johnson's plucky performance, and a beaming Retton waving from the stands. Moments later, when Liukin won, she threw her arms around her dad and waved to the crowd.

The other big story was whether the Chinese female gymnasts were underage, something Michaels, analyst Tim Daggett and producer Billy Matthews had talked about for months. They wanted the viewers to decide.

"When the American viewing public takes a look at these girls with super close-ups, people will make their own decision," Michaels said before the competition. "It's not like we singled out the Chinese. That's the pattern of how I cover this stuff—with a lot of extreme close-ups. The problem is no matter what you do, these gymnasts look bigger on TV than they do in person. It's all about framing. What does she look like in relationship to the beam? The tight shots don't show you anything other than her face. I was trying to show it so that people watching on TV would go, 'Oh my God, they're so little,' instead of making them look gigantic."

Early in the competition, as a Chinese gymnast performed, the announcer asked, "Does she look 16? Judge for yourself."

Before the Games, Michaels thought he had worked out all the kinks. But just before the second rotation of the men's team finals (where the U.S. won bronze), Michaels heard a pop! "I looked down and there's five black holes." A bad battery charger had crashed all five of his handheld cameras.

"I had this great sense of calm," he says, and he used his hard cameras and a couple of world-feed cameras while the crew fixed the problem in 10 minutes.

Perhaps one explanation for Michaels' calm was that each morning he and his crew practiced tai chi in a courtyard below their production office. They banged a gong borrowed from the Beijing Symphony. "It was not about the tai chi; it was about the spirit [of being in China]," Michaels says.

But once the competition started, Michaels was totally absorbed in the heat of the battle. "When I'm in there working, I'm anywhere. Except for hearing the Chinese anthem all the time, I wouldn't have known I was in China."

After the furious week of swimming and gymnastics, some predicted NBC's ratings would fall in the second week with track and field the center stage event. Although these were not broadcast live as were gymnastics and swimming, Andy Rosenberg shot and recorded them live.

FAST TRACK: Andy Rosenberg fixed his camera on Usain Bolt

FAST TRACK: Andy Rosenberg fixed his camera on Usain Bolt

as he won the 100 meter dash. (Credit: Bob Thomas)

"There's a different energy to it. In the 100 [meter dash], you get one shot and it takes 9.69 seconds. You don't get a redo. 'Oh, sorry I missed that. Could you do that again for me?' There are no second takes in live sports, which is why it is one of the great adrenaline rushes."

NBC averaged 27.7 million nightly viewers for the 17-day Olympics, in large part because of Usain Bolt, who, if not for Phelps, might have been Beijing's defining personality. Rosenberg, who has directed NBC's track and field coverage since 1988, used 20 NBC cameras and 25 replay machines at the Bird's Nest, including handhelds and Super Slo-Mos, to capture the action. He also had a camera on the last turn for oval races like the 400 meter dash, to show the runners after they come out of their staggered start. This way viewers can see who is ahead as the final 100 meters begins. "Everyone else covers it from the finish line camera where it's hard to see who is actually ahead and by how much," he says.

During the prelims, it was clear that Bolt was the fastest runner and the biggest personality. "You can't script charisma," Rosenberg says. "As a director I was looking to bring the character that he is to the viewer at home. It is a race and so at some point it is, pardon the pun, the nuts and bolts. But there is also the emotion that surrounds it. That's what I'm looking for in any sport. I want to document the activity in the most captivating way."

Rosenberg set up the 100 by introducing the athletes. He was astounded when Bolt started dancing. "I've never seen an athlete do that." He used a handheld camera from a low angle to show the runners before they exploded from the blocks. Another handheld provided intense shots of their faces: "I want to see their eyes," says Rosenberg.

The gun went off and Rosenberg cut to the finish line camera for the fastest 100 meters ever. "Normally what I'm watching for is a really tight finish so that I can cut as quickly as possible to the one who I visually see cross the line first. You want to see the reaction of the winner, not the person who came in second. I've got all my juices flowing. I'm on edge as those 9.69 seconds are happening. I want this to look like I did it all in post but I'm doing it live. I'm intense in anticipation of what's about to unfold. Who is going to be proclaimed the world's fastest man?"

As they're running, it's clear the race is off the charts. "Bolt is winning by open water," he says. "In a sprint, you're supposed to win by inches, not lengths."

And then Bolt celebrated with 10 meters to go. "It actually leaves that lingering question: How fast could he have gone?"

"So now, let's go along for the ride with him," Rosenberg continues, "Let's capture his celebration. I have cameras plotted around, and one immediately after the finish line. I've got a head-on, Super Slo-Mo camera that's isolated on him the whole race. That will show that moment of exultation as he crosses the line. Then I've got a camera that's another 30 or 40 meters away, around the turn. That's likely my next cut because he's going to continue running through. He's running so fast he's not going to come to a quick stop. I've got a handheld and the world feed has a couple of handheld cameras that are chasing him down as he goes on his victory lap."

Rosenberg told his handhelds to follow Bolt. He asked one to widen out to show the crowd cheering. Then he cut to a close-up. "I wanted to see Bolt's face" as he embraced someone on the sidelines and finally stopped.

"I've been doing sports TV for 36 years," Rosenberg says. "It's a combination of planning—preparing cameramen by knowing who the athletes are and where to put the isolates. Then there's that visceral instinct of reacting to what you see."

Four days later, before the 200 meter race, Rosenberg's camera caught Bolt mugging in the walkout area, holding rabbit ears behind U.S. sprinter Wallace Spearmon's head. "If you don't have the cameras in the right place, you're not going to see any of that," he says.

For the 200 meter race, the production team (including an associate director, producer, the announcers, cameramen and a track spotter) wondered what Bolt would do. Would he run all the way through? What kind of celebration would he have? They prepared.

Rosenberg used a tracking camera to show Bolt's start. "He jumped to the front. You had that sense of just how fast he was from the start," says Rosenberg, who also used a tracking camera to show how effectively the 6'5" Bolt took the turn. Bolt set the 200 meter world record of 19.30 seconds while running into a head wind.

He then ran all the way through the finish line. But instead of running to the far end, he fell flat on his back. "Just hang with the handheld camera for a close-up," Rosenberg says. "You're making instantaneous decisions about whether to cut or edit. Sometimes you just sit with what you've got because you know something is about to unfold."

Over the years Rosenberg conceived and helped develop the tracking camera, a robotic that moves along on a rail with the sprinters. "Speed is the one thing that doesn't translate as well on TV," he says. While many directors would cut to the finish-line camera in a race down the home stretch, Rosenberg will often cut to the tracking camera. He used it to catch Sanya Richards' dramatic come-from-behind victory over Russia's Anastasia Kapachinskaya in the women's 4 x 400-meter relay.

"I lingered on the tracking camera so that you could see her pass. Visually it knocks your socks off. But I need to bring the viewer back for the finish. I have that tug and pull every time I go to that tracking camera."

Before the Games, Michaels had time to explore Beijing. He hung out with locals, went to "crazy" restaurants and arts co-ops. While in Beijing, Michaels could not gain access to some gymnastics blogs on the Internet, but despite the restrictions, he felt the U.S. press coverage was distorted, akin to a reporter from China coming to the U.S. and focusing only on conditions in West Virginia coal mines. "The people were amazingly friendly and helpful. I'm sure they rounded up all the homeless people and took all the crazy people off the street. The streets were immaculate. There are all these fantastic buildings, but you don't know if anybody's in them or not. It is a Communist country, after all."

Bucky Gunts had done his sightseeing on previous trips. Besides the opening ceremony, he directed the primetime studio show. Keeping track of 100 monitors, he coordinated the cameras on Bob Costas and integrated live or taped sports for the show.

When Liukin and Johnson stopped by after the all-around competition, Gunts was taken by their graciousness. "It wasn't like Nancy Kerrigan and Tanya Harding," Gunts jokes. "They're competitors and yet when it's over, they're friends." So Gunts found himself staying on the two-shot of the girls. "They were looking at each other and reacting. That was the story, not them individually but them together."

Another high point was the interview Costas did after Phelps tied Mark Spitz's record. Esocoff's crew handled Phelps at the pool, a Detroit crew caught Spitz, and Gunts had Costas. NBC aired archival shots of Spitz, with a mustache and a full head of hair, racing in a Speedo. Indeed, as Phelps said, a lot has changed in swimming. The Spitz archival footage aside, NBC limited most features to no more than 45 seconds, preferring to go with the live action.

With so many venues, studios, graphics and networks in Beijing and New York, Gunts anticipated more problems. NBC, which had 3,000 people in Beijing and 600 in New York, aired and streamed 3,600 hours of coverage, more than all other Summer Olympics combined. "Who would have thought all these things would work out so well?" says Gunts.

Gunts, who attributes the success to extensive planning, has already visited Vancouver five times in preparation for the 2010 Winter Olympics. But for the moment, Gunts and the other directors are basking in the aftermath of Beijing.

"For the world to be able to bring its athletes together and compete in a relatively peaceful situation is extraordinary," Rosenberg says. "Ultimately, it's the sports that are compelling. That's why I love doing this."