BY JEFFREY RESSNER

A freezing cold bedroom shakes, rocks and quakes. Green gooey vomit spews from a little girl's parched lips. Ghastly demons appear-some barely visible in fleeting subliminal cuts, others in ghoulish tableaus. The powerful imagery featured in the climactic sequence of William Friedkin's The Exorcist seems familiar and iconic now. Made in 1973, well before the advent of digital special effects and computer animation, The Exorcist stands as a testament to imaginative filmmaking, a classic that still has the ability to shock and scare audiences.

A freezing cold bedroom shakes, rocks and quakes. Green gooey vomit spews from a little girl's parched lips. Ghastly demons appear-some barely visible in fleeting subliminal cuts, others in ghoulish tableaus. The powerful imagery featured in the climactic sequence of William Friedkin's The Exorcist seems familiar and iconic now. Made in 1973, well before the advent of digital special effects and computer animation, The Exorcist stands as a testament to imaginative filmmaking, a classic that still has the ability to shock and scare audiences.

The scene Friedkin describes below depicts the ultimate struggle of faith as two Jesuit priests-played by a young Jason Miller and a wizened Max von Sydow-confront ancient demons, which have possessed the body of an innocent 12-year-old girl (Linda Blair).

The exorcism section took nearly a month to shoot and was filmed entirely in sequence, recalls Friedkin, who says he was only able to complete about five shots a day due to the complexity and cold temperature required. Most of it was shot with one camera, and all the sound was recorded separately because of the unusual voices and audio gimmicks. By employing innovative mechanical effects, life-sized puppets, editing tricks, creative lighting and other techniques, Friedkin and his team created a scene that remains unique in the history of horror films. "I'll be honest with you," says the director, proud of the film magic he achieved without the help of computers or other digital equipment. "If I was making The Exorcist today, I still wouldn't use much CGI."

In the novel, William Peter Blatty's description of Father Merrin (von Sydow) arriving outside the home of the child's mother says he was standing under a streetlight in a misty glow 'like a melancholy traveler frozen in time.' I had to find a way to visualize that, and I allowed a full day to light the scene. We used arc lights and troopers to light the street, in addition to boosting the practical lighting like the streetlamps. After a great deal of trial and error, we filmed on the second night. The painting that inspired me was René Magritte's The Empire of Light that depicted a small house at night lit by a streetlamp, but the sky in the painting is flat-out daylight. It's an amazing surrealistic image.

This is Linda Blair wearing contact lenses that made her eyes gleam in a beastly fashion. We used just one soft light 'barned' across her face so only a thin strip of light caught her eyes in the dark bedroom. It's probably a 75 mm lens, because we used that a lot. Linda was a real trooper. She had never acted before; she had only done modeling work, and we saw her after looking at thousands of 11- to 12-year-old girls across the country. We had even started going over 14 and 16 year olds who looked younger, and then one day Linda's mother brought her in to see me, unannounced. The minute I saw her and talked to her, I knew that she understood the movie and could deal with it.

When movies wanted to show actors' breath in a winter scene, they'd film at a place called the Glendale Ice House, where they manufactured gigantic bricks of ice. The Magnificent Ambersons, Lost Horizon and many other films were shot there. But by the time we made The Exorcist that place was long gone. So what we did was place a gigantic restaurant air conditioner across the top of the set. At the end of each day's shooting, we turned on the A/C all night so by the next morning it was 40 below zero. We also had to set little clip-lights on the floor and on the back of furniture-if you just had the actors talking and didn't highlight their breath with lighting, it wasn't going to show up on film.

I decided early on not to do the usual things or give the movie any kind of spooky lights that you typically saw in horror films. Instead, it all had to transform from something real and from a source. So you can see on the left side of the frame that there's one lamp that's turned off, while the lamp on the other side is on. And of course, we added some as well. My cinematographer, Owen Roizman, was very careful to keep the lighting cold and sort of eerie, but all of it came from a source. The lights were all filtered for night, and it was an interior, and everything is given a kind of realistic foundation.

Most of this scene, with a few exceptions, was shot from Father Karras' (Miller's) point of view. This angle, in which she's about to spit vomit on Merrin, is pure POV. Over the years, everyone refers to the vomit here as pea soup, but it was really porridge with pea soup coloring-it had a much better texture than pure pea soup. We used a very thin plastic tube that ran from the side of Linda's mouth underneath her nightgown right down to the floor, where a special effects technician was stationed with a jerry-rigged pump and a hand crank. On cue, she would tilt her head the right way and he would pump the stuff up through the tube and, seemingly, out of her mouth.

The consistency of the porridge is what determined the speed at which it would move through the pump. Of course, in each case where you see Linda vomiting there would at first be an accompanying shot of Father Karras, and then Father Merrin, where we pumped it straight at them as a crosscut. Before we started, I prepared Max by informing him what had actually happened during an actual exorcism, including three exorcisms that the Catholic Church recognized as being authentic since 1900. We had an expert from the church who had experience with all of this material. So Max was well prepared, and he knew that we weren't just doing goofy stuff, that this sort of thing happened in the authentic cases.

I never planned to use these shots-they were from makeup tests with Linda's double. I didn't use that makeup because it seemed too theatrical, too much like other horror films. But I thought if we could just show it in one or two frames that it would be pretty frightening. I wound up using them as subliminal cuts, no more than two or three frames, an eighth of a second or so. When we were editing the film on a Moviola, we took some frames of the makeup tests and cut them into the work print as an experiment. They worked very effectively because the young girl was supposedly possessed by several different demons; it looked as though it was the manifestation of these other personalities.

There was never a mention of the girl's head turning around in the book or the screenplay. But there was a scene in the book in which a detective talks about someone whose head had been turned completely backward. We referenced that in the film, and I felt we had to show that the demon had the power to also turn the little girl's head around. So makeup artist Dick Smith devised a life-size doll and the shot starts with Linda twisting her head as far as she can, then we see Father Karras' eyes, and then we cut back to the doll's head swiveling. We also had a plastic tube that ran through the doll's body to her mouth, and blew smoke through it after the head swiveled completely around. It just added to the illusion.

The bedroom set was actually built on top of a giant gimble, and individual items like the lamps and the blankets were all attached to monofilament fibers. At one point, the demon causes a kind of earthquake in the room and it shatters apart in an attempt to show her powers to Father Merrin. The set was rocked back and forth mechanically by about 20 stagehands using large levers that were crisscrossed under the set. At the same time, other stagehands were pulling on the monofilaments and causing the lamps and blankets and other items to fly around the room. The effects were all done mechanically and still work for audiences because it's the expectancy, the belief in the possibility we created that prepares the audience for what happens.

For the levitation scene, we created an illusion the way a magician does-we tricked the eyes. Linda was in a bodysuit underneath her nightgown, and there were lots of monofilaments attached to the gown holding her up. She only weighed around 80 pounds at the time. The monofilaments were all attached to a gigantic plate situated above the set and it allowed her to be pulled up by a group of stagehands as if she was levitating. It took a full week to perfect this. The shadows helped take your eye away from the wires, and even when I went back to the film for a DVD release in 2000, I didn't have to digitally erase any wires.

I added this shot of the Mesopotamian devil called Pazuzu, the first demon Father Merrin sees at the beginning of the film in Iraq, and suddenly put him in the little girl's bedroom. We had to close the room in, fog the place up, and light it from behind and below. Some of the lights were floodlamps, two of them from below shining on the wall, but most of them were small 750s on the floor, behind the demon and in front of Linda, just enough to get the job done and not get a lot of bounce light.

In the original version of the film, Karras yells, 'Take me! Come into me!' at the demon, and you see Jason Miller do that with his face all red and contorted. There's a quick jump cut and then you see him coming forward with demonic eyes, which we did with contact lenses in two separate shots to indicate there was a sudden leap of the devil from the little girl's body into Karras' body. That jump cut in the original version always bothered me, but it was the best I could do at the time. Finally, in 2000, I CGI-ed the two shots so they blended together in the same frame to make the transition between Karras who was not possessed, and then Karras becoming possessed.

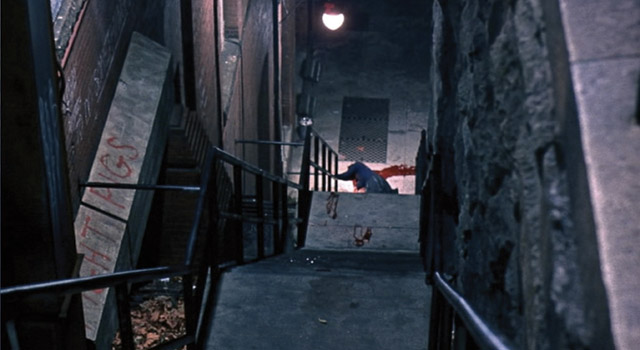

When we were on the set in New York, Jason ran out the bedroom window, and then quickly landed on a mat that was about three feet below. That was followed by this shot of the stuntman on the Georgetown set, flying out the window and performing a tremendous jump as the glass shatters behind him. It was about a 30-foot jump and we did it all in one take. It had to be measured and sussed out perfectly, because you weren't going to ask somebody to do this more than once. Later you see the same stuntman tumbling down six flights of steps. I was trying to document the reality of a guy going out a window and show it all very closely from head to toe.

This is a bird's-eye view of Karras lying in a pool of blood at the bottom of the stairs, seen from the perspective of where he jumped. When we shot from the top we couldn't get the angle you see here, so we constructed a platform projecting out about 15 feet so the angle wouldn't seem quite as steep. I originally tried to make it a wider shot to get an idea of how long his fall was, but that long shot didn't have as much impact as a tighter lens. When I filmed this, I always thought of the ending of Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities, in which Sydney Carton gives his life to save his friend-a 'far, far better thing' he does then he had ever done before.