BY ROBERT ABELE

When you've elected to undertake a filmmaking task as massive as the back-to-back shoots of the two Pirates of the Caribbean sequels, says director Gore Verbinski, planning is one thing. But adapting is the name of the game.

Verbinski filmed the wry and rollicking Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl as a stand-alone picture, but its enormous worldwide success in 2003 fueled a desire to return to its unusual family-film blend of seafaring derring-do, romance, comedy and the supernatural. "I was hugely influenced by Sergio Leone when I was a kid," he says. "That majestic epic tapestry with piss and vinegar and dirt under your fingernails."

So after spending the next year shooting The Weather Man, a low-key character study, Verbinski and writers Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio took the loose strands and untapped ideas from the first Pirates film to craft a trilogy, continuing with Dead Man's Chest (2006) and culminating with At World's End (2007). It was a Herculean venture that would ultimately take three years of Verbinski's life.

"It's this strange kind of improvisational, intuitive process, with 400 people sort of flocking and ducking and weaving at the same time," explains Verbinski. "When you have a really amazing crew and you're shooting for 260 days, you pretty much wake up knowing fate is going to throw you a curveball, and you're going to have to adjust."

That curveball came when production on the second film, Dead Man's Chest, arrived in the Bahamas. After rigorous location work in Dominica, St. Vincent's and the Exumas, the remainder of the two films was to be shot at a new tank facility that the Bahamas government had arranged to build for Disney. Fancy new gimbals would allow the production to use full-size seaworthy ships for rigging, rather than having to construct smaller tank models of the ships.

However, when Verbinski and company arrived in Freeport the site was still under construction. "The bulldozers were still digging the tank," he recalls. "So we took a two-month hiatus, which pushed us into hurricane season." The facility still wasn't completed. "We had to adjust. We anchored, drove wake boats around trying to create swells, and repurposed the second movie and, to a great degree, the third. We just willed it into existence. By the time the gimbal was built, I think we used it for two scenes."

Because of the delay and rescheduling, it became clear the third film wouldn't finish shooting before the second film was in theaters as planned. So crew members had to work four months longer than expected. As Verbinski puts it, "There are times where directing is pure art, and there are times when it's logistics, a lot of math."

Early in his career, directing was also a lot about selling products, since the UCLA grad got his start in commercials and music videos. But with his move to features like the slapstick romp Mousehunt (1997) and the dreamlike horror flick The Ring (2002), Verbinski displayed a visually inventive, artistic sensibility that could also translate to the box office. It might have seemed daunting to a lot of filmmakers to try and revive the left-for-dead pirate flick—not to mention shepherd a project based on a beloved theme park attraction—but Verbinski relished the challenge the first Pirates film represented. "I like being the underdog, being in a place where people don't believe in what you're doing."

It's Verbinski's belief that audiences crave something new, and that you have to make that happen, even when a big studio only seems to want, as he puts it, "something they have data on." Johnny Depp's iconoclastic take on Captain Jack Sparrow, for instance, was one of those bold moves Verbinski knew would need defending to Disney. "That was a big discussion: 'Is he drunk? Is he gay?'" recalls Verbinski, who is a fan of Monty Python and absurdist theater and was looking to subvert pirate-genre archetypes. "I was like, 'Don't worry, he doesn't have to carry the love story. We've got Orlando Bloom and Keira Knightley for that.' Johnny is like Lee Marvin in Cat Ballou. He gets to bump through the story and have his own agenda. Tonally it's building that balance, that construct of adventure with absurdity."

The huge success of Pirates, however, led to a different dilemma when the idea to film two sequels back-to-back became a reality. "The scariest thing is the studio's not nervous anymore. You think you're being viral and creating a revolution, and they're going, 'Great, keep doing that thing you do!' So it was just trying to conjure the feeling that we were still dangerous, pushing the boundaries with some of the humor, and with the third movie, being a little surreal."

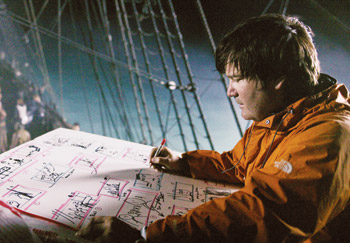

Perhaps most alarming is the fact that both sequels were prepped without scripts. Like the evolutionary methods of making animated movies, Verbinski wanted a process built on a combination of big-picture forethought and intuitive brainstorming. "There's this sort of living collage of location photos, outlines, cards, storyboard fragments, casting notes, all pinned up on four walls in your office, and you're able to walk up and go, 'This is the first act; here's an inciting incident; here we're doing character work until we get to this big moment.' You're building the mosaic. We prepped to the point where we had to take guesses at how many days it was going to take to shoot a scene that didn't exist yet." And in true pirate fashion, perhaps, this way of working allowed him to get away with more, "because there's really no time for any kind of approval process."

First AD Peter Kohn, who was onboard for the first two films and part of the third (David H. Venghaus Jr. was 1st AD on the third), says that everyone knew what they had to achieve and wanted to push it beyond the first film. "Disney, obviously, and everybody were chomping at the bit for a schedule, which comes down to myself," he says, still excited by the adventure. "So Gore and I would sit day after day in a room and start to piece the film together, using index cards and stick figure drawings that he drew. Gore, being a visualist, had in his mind the entire second film—the third film was still being flushed out. So we would literally take a sequence and break it down into how many days we felt that would be. And then from that, I would compose a schedule."

It's part of the "tinkerer's philosophy" Verbinski believes in that's all about "increasing your odds for the creative accident. I like to have a plan, but then let that plan evolve—like tasting a soup as you're making it and changing the ingredients." The opportunities can be big, like allowing Depp's offbeat performance to flourish, or small, day-of-shooting notions, like calling the prop guy to whip up a frozen toe for a new gag. "You've got these wonderful craftsmen and trucks full of tools. You can constantly come up with ideas."

Verbinski is the kind of director who rarely leaves the set, says Kohn. "Trailer time really doesn't exist for Gore. We have an expression called ABS, which stands for 'Always Be Shooting.' So even if we're not ready, we shoot. If you wait around for that perfect shot, you've kind of blown the day. So we always would find the minutest thing, whatever it is, so we'd be shooting something. That sort of approach gives you so much more to work with in the cutting room."

For Verbinski to be able to work that way, he needs an atmosphere of communication. He wants everybody in the loop, not just a few key actors and craftsmen around the camera. "I'm not a cards-close-to-the-vest director," he says. "I share the vision with everybody. So I'll show up on set and I'll do the shot list for the day, the storyboard, and everybody can come by and see what the day's work is. Some actors don't want to know, and that's cool. But Geoffrey Rush [who played Barbossa] would constantly look at the board. 'Oh, I see, you're going to play that line off-camera and use my reaction for that moment.'" The shot list on view, of course, may not ultimately reflect exactly how the day proceeds, but its presence keeps cast and crew in sync as to what the goals are. "The crew wants to feel like they're contributing to something, that they're getting their thumbprints on the sculpture as it's being passed around. Morale is a function of communication."

On Verbinski's set, nobody on his team has to worry about when they will get to talk to the director next. "If we're filming in Dominica, we'll rent a house, and I'll have the DP and camera operator stay there, and maybe the gaffer, because after work we'll debate about what's coming up tomorrow."

Needless to say, scheduling is an invaluable element in making movies this enormous, which meant Verbinski relied on his first assistant director to make sure efficiency and actors' needs peacefully coexisted. "With Gore," says Kohn, "he visualizes the scenes so that he's able to construct them shot-by-shot. So I would already have a shot list for each scene before commencing the first day of principal photography, which if you look at a film like Pirates, that's a lot of shots."

"It's looking at a massive 200-day schedule, and being able to draw back and see the connections and start to understand," adds Verbinski. "Quite often there will be a studio mandate to get all this type of work done, but you have to think about morale. Actors want to act. After 20 days of sword fighting, give them a two-page dialogue scene, you know?"

STORM WARNING: For the 20-minute maelstrom sequence in the third film,

STORM WARNING: For the 20-minute maelstrom sequence in the third film,

Verbinski used a full-size replica with wind, firing cannons, smoke and rain. Verbinski is the kind of director who rarely leaves the set.

Verbinski is the kind of director who rarely leaves the set.

(Photo Credit: All photos Disney)Conversely, Verbinski finds the use of second units a path to inefficiency, because he'll inevitably wish he'd shot those scenes himself. "How you're supposed to do things is the director deals with the actors, and blowing up ships they farm out to a second unit director. Well that's the fun stuff, and I want to be there for that, too. It comes down to composition. Those decisions—a little more headroom, tilt left, pan right, whip pan here—I have to make."

So Verbinski's method is to have a splinter unit of the main crew stay behind after a big scene is filmed and give them hands-on instruction so there won't be a need for re-shoots later. This team includes not just the second unit head but also perhaps the visual effects supervisor or the stunt coordinator. "I'll grab a viewfinder and walk the shots with the lenses, and leave them there for a couple of days to pick up elements or plates or effects. Then they reconvene with the main body."

Because of his advertising and music video background, Verbinski has long been comfortable working with visual effects. While the Pirates movies are effects-heavy, Verbinski, whenever possible, provided the computer guys with something filmed on camera to work with. "In the first film there's a sequence where a window is opened and you see a matte painting of Port Royal outside. We were forced to shoot it on a stage because it's the only time you see it, and the matte painting never worked. In the second film, we were able to build [Lord] Beckett's office on location, so you open the windows, you get the real sun, and we add a few ships to an environment that's inherently real. Let God provide reality and enhance it; that's always better than 'Oh, we'll just do that in post.'"

For the virtuosic maelstrom sequence in the third film, a 20-minute battle in an oceanic whirlpool that Verbinski painstakingly pre-visualized, it made more sense to build full-size replicas on a large indoor set. "To fabricate that amount of mid-ground on that amount of shots would cost so much in post, you're better off having a ship. It's cheaper to have the physical boats and put people in them, because then you're just printing deep backgrounds in CG. So we had wind, cannons firing, smoke, rain hitting people in the face. We couldn't even see the blue screens most of the time, because there was so much water and haze. But at the end of the day, we weren't looking for clean mattes. If you were really in a maelstrom, you probably could barely see the person 20 feet away from you, you know? So in a way, you embrace that as a means of getting through it."

Whether he was creating the reality as large as possible on a soundstage or in the open air in far-flung locales, Verbinski sensed that the Pirates movies represented a fading ideal, both as mythic stories and as epic filmmaking.

"The films themselves are dealing with the post-modern Western idea that the railroad has come and there's no place for the gunfighter anymore," he says. "We resurrect the pirate genre and then show its demise, that the myths are dying. And it's ironic because I don't think they're going to let us take 400 people on distant locations as much anymore, with more and more being done on a computer. So I felt like there was a spirit of that David Lean approach, where you're embracing the raw elements and celebrating what they provide. And that's the end of an era."