BY GARY GIDDINS

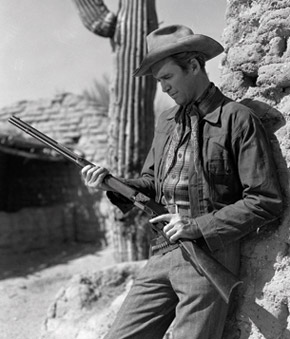

WINCHESTER '73 (1950) (Credit: NBC Universal)

WINCHESTER '73 (1950) (Credit: NBC Universal)

Anthony Mann's movies are often celebrated for their formal logic and psychological astuteness, as well as their intelligent use of space, perspective, and lighting. But the main thing to be said about them is that they are infinitely entertaining and beautiful to behold. In recent years, many of his best films have been released on DVD in appropriately gorgeous transfers, ranging from the fierce black-and-white chiaroscuro of The Furies, to the deeply saturated hues of Bend of the River, to the muted colors and majestic vistas of El Cid. Often from the first shot, which establishes the landscape and the hero's place in it, Mann's greatest work suggests a masterly confidence that puts the story front and center.

Mann had a curious if not unique career, rising from the deepest crypts of Poverty Row to the crest of profligate spectacle. Financing aside, he remained focused and stylish in examining his key, interrelated themes: What is heroism and what binds the individual to society? These are big issues, and Mann approached them through the most reliable of cinematic filters—the genre movie.

Yet unlike directors who worked in many genres simultaneously, Mann tended to focus on one before moving to the next. His work falls into four key periods, each reflecting his directorial clout at the time. In the first, from 1942 to 1946, he learned his trade on minimal budgets, grinding out 10 programmers. Even so, his pictorial and dramatic abilities produced savory moments, including a purview of low-rent vaudeville in The Great Flamarion; a valentine to wartime sentimentality in The Bamboo Blonde; and a violently subverted "women's picture" in Strange Impersonation.

Between 1947 and 1950, Mann found his forte in B crime thrillers of the sort later designated as noir. In eight terse movies, he helped to define the form, collaborating with like-minded craftsmen, including screenwriter John C. Higgins and cinematographer John Alton. In pictures like Railroaded!, Raw Deal, T-Men, and He Walked by Night (credited to Albert Werker, but mostly directed by Mann), he focused on urban bottom-feeders, emphasizing the sudden brutality and sadistic pleasure it afforded its perpetrators. This was exemplified by John Ireland's character in Railroaded!, who perfumes his bullets. At this stage, Mann found greater interest in his villains than his heroes who project a stolid anonymity. He also brought noir shadows and moral upheavals to the French Revolution in Reign of Terror, and explored location shooting in Side Street (Warner Home Video), in which city skyscrapers are filmed as though they were the canyons of the old West.

Then, suddenly, everything changed for Mann. He embraced the Western with astonishing poise, rivaling John Ford in producing the most original and consistent work in the idiom during the 1950s. This included in particular a quintet with James Stewart that re-established the actor's career, recasting him from the decent fellow he created in pre-war films to the loner with a secret and bent on revenge. Other directors found parallels between urban paranoia and Western lawlessness—Robert Wise, André De Toth, Sam Fuller, Budd Boetticher—but Mann did the most to change the look and feel of the Western, giving it a raw, psychological urgency. He maintained a stable of supporting actors (most frequently Harry Morgan, Charles McGraw, and J. C. Flippen), and instead of Ford's Monument Valley found his own look: craggy mountains and desert sands.

Working with dependable writers, chiefly Borden Chase, Mann focused on the integration of personality, opposing his heroes with doubles who must be destroyed before the character can claim his rightful place. In each of the Stewart films, the "hero" is determined to kill an enemy from his own dubious past. In the first of them, Winchester '73 (1950), Stewart must destroy his patricidal brother. The film is constructed as a round, with characters of every moral stripe tied together by their successive possession of the eponymous rifle. In the end, Stewart's good son, facing an ambiguous future, is left to the ministrations of an aging sidekick and a woman of doubtful virtue.

Winchester '73 was one of three Westerns Mann filmed between August 1949 and March 1950, and the only one that proved a major success. MGM had postponed the release of Mann's Devil's Doorway, a study of the racism suffered by a Native American Medal of Honor recipient, until Delmar Daves' Broken Arrow (also starring Stewart) made a fortune as the first Western to treat the subject of injustice to Indians. Perhaps the most visually impressive of this trio of Mann Westerns is The Furies, a loose reworking of Aeschylus' Oresteia, fraught with incestuous conflict (daughter Barbara Stanwyck vs. patriarch Walter Huston), miscegenation, vengeance, and startling violence.

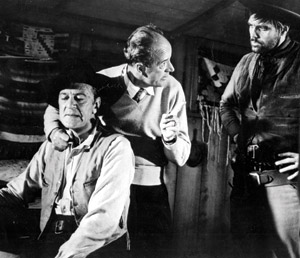

TOUGH GUY: Mann (center) directs Gary Cooper and Jack Lord

TOUGH GUY: Mann (center) directs Gary Cooper and Jack Lord

in MAN OF THE WEST (1958) (Credit: Photofest)

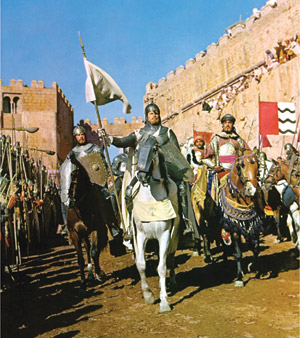

EL CID (1961) (Credit: Weinstein Co.)

Reunited with Stewart for Bend of the River (1951), Mann brought all the components of his style to his first color film, in which the nature of men is delineated by the landscape they either settle or defy. The personality split is made explicit when Stewart's character, Glyn, saves his apparent double, Cole (Arthur Kennedy), from being hung. Both have a secret past as murderous border raiders during the Civil War, but Glyn is determined to prove he has changed. The cinematography, representing the pinnacle of Irving Glassberg's career, is sumptuous. Dappled with reds and deep blues and frequently shot at night, it took in the wilderness, town activity, and river life.

Bend of the River created a paradigm for the next three Mann-Stewart Westerns—The Naked Spur (1953), a five-hander of mutual suspicions and betrayals played out on a rocky peak (the naked spur of the title); The Far Country (1955), featuring Stewart as a guide reluctant to take responsibility; and The Man from Laramie (1955), in which his vengeance-bent ranger has to contend with another charming doppelgänger played by Arthur Kennedy. In a characteristic burst of Mann violence, a rancher's corrupt son shoots Stewart in the hand and the camera speeds in for a close-up as Stewart screams, in the agony of pain and astonishment, "You scum!"

Mann's morality is concerned less with the conflict between good and evil than between niceness and corruption. In Bend of the River, one villain says of another villain, he seemed like a nice guy. The leader of the settlers responds, "He was until he found gold." The three non-Western films Mann made with Stewart in the 1950s suffer from a surfeit of niceness with too little opposition, especially given the sugary support of June Allyson in Strategic Air Command and The Glenn Miller Story—the latter a fantasy of wartime nostalgia in which characters repeatedly acknowledge each other's niceness.

At the same time, Mann made two far more dour films starring Robert Ryan, who played the villain in The Naked Spur. The Korean War film, Men in War (1957) and the barnyard romp, God's Little Acre (1958) are complementary, existential parables. One is tragic, the other absurdist, but both films deal with a plot of earth, whether as a battle objective or a farmer's dream, that is ultimately revealed as mere dirt. The idea that salvation is won by refusing to surrender to doubt or futility is pursued in Mann's most emotionally hysterical Western, Man of the West (1958), in which a reformed outlaw (Gary Cooper) has to destroy the criminal family that raised him before he can assert his place in society. He proves himself but without finding a home. All these films have been issued on DVD, though God's Little Acre and Men in War are presently out of print.

With Cimarron, the 1960 remake of Edna Ferber's melodrama about the opening up of Oklahoma (released as a Warner DVD that does justice to the Cinemascope frame and Robert Surtees' photography), Mann set out to show the Western hero easily surviving outlaws only to be done in by politics and finance. The picture takes on miscegenation, racism against Indians, and anti-Semitism, but Mann walked off the project when forced to abandon location shooting and accept a revised script favoring the hero's wife. (Charles Walters replaced him.) He was fired early on from Spartacus, after tangling with producer-star Kirk Douglas. Still, these two films served as transitional episodes culminating in his triumphant direction of El Cid, the most successful of producer Samuel Bronston's road show spectacles. It was filmed in Spain with some of the grandest sets, natural and manmade, since D. W. Griffith's Intolerance.

The financing for the blockbuster El Cid (1961) and the second Bronston-Mann collaboration, The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), a debacle that killed the era of elephantine epics, was so complicated it was argued in courtrooms for years. But the two films are treasures of a kind that can never be made in the age of computer graphics. If Roman Empire loses much of its grandeur on a television screen (through no fault of the excellent DVD transfer), El Cid remains the most compelling and intelligent of the costume marathons designed to seduce audiences from the small screen. Ironically, that is now the only place they can be seen.

El Cid's glorious panoramas encompass the castles and plains of Madrid. Luminously photographed by Robert Krasker and thumpingly scored by Miklos Rozsa, the film, with its haunting climax, unfolds like a living tapestry in the recent 35 mm DVD transfer of the 70 mm original. Yet El Cid differs from Mann's earlier work in more than size: It is a driven and humorless picture in which moral absolution is embodied in the Cid's increasing conviction that he is chosen. Gone are the charming rogues, comical asides, and ambivalent gallants of Mann's noirs and Westerns. But in Charlton Heston and Sophia Loren, Mann had stars large enough to support the spectacle.

After the failure of Roman Empire, Mann was a freelance looking for agreeable projects. The Heroes of Telemark (1965), a World War II adventure set in Norway, did not fill the bill, and he died in 1967 at age 60 while shooting A Dandy in Aspic (1968, taken over by its star Laurence Harvey). Thanks to DVD, we can line up most of Mann's films chronologically and follow the largely rewarding—and often surprising—progression of a gifted filmmaker who expanded movie genres to suit an increasingly distinctive vision.