BY JEANNE DORIN-MCDOWELL

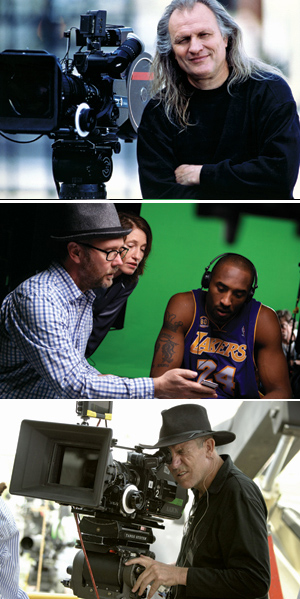

(Top to bottom) Tim Ashbire; Nicolai Fugslig; Dante Ariola

(Top to bottom) Tim Ashbire; Nicolai Fugslig; Dante Ariola

(Credits: Big Lawn Films (top); MJZ/Weiden+Kennedy)

For his latest television commercial for Ford, DGA Award-winning director Nicolai Fugslig wrapped the entire Universal Studios back lot—trees and all—in canvas. Many directors would have found the sheer magnitude of the production daunting, if not downright impossible. But for Fugslig, it's all in a day's work. Having made his name directing such extravaganzas as "Tipping Point" for Guinness (the most expensive ad in the company's history) and "Bouncy Ball" for Sony's Bravia LCD television, featuring 250,000 multi-colored balls bouncing down a street in San Francisco, Fugslig's creative comfort zone lies in big productions. "I love these epic spots," he says. "They're cinematic."

It's a sentiment echoed throughout the landscape of television commercial production these days as directors turn out ads that are nothing less than small-screen cinematic wonders. They're doing it with the help of technological advances such as CGI, digitalization and special effects and, in other cases, by making the decision to go intentionally low-tech. But never before have commercial directors had such a treasure chest of creative options, many of which didn't even exist a decade ago.

As new technologies have become available, they have not only expanded the creative portfolios of directors but, to a certain extent, also affected the way commercials are made. It's also shifted the balance, making postproduction a bigger part of the process than ever before (although not all commercial directors are involved in post). While the goal for most directors is still to shoot in camera, the job is finished and refined in post. "You spend as much time in postproduction as you do behind the camera," says Leslie Dektor.

In some cases, the focus of directors' creative energy is shifting. For instance, for a 2001 SUV commercial, director David Cornell recalls the challenge of getting a Jeep onto a mountaintop in South Africa, then waiting for the sun to set so he could capture just the lighting he wanted. Today, Cornell notes, he can achieve that same scene using digital effects in postproduction. However, even with digital effects, it is still incumbent on the director to envision exactly how the scene should look—the lighting on the Jeep or the height of the mountain. The director's role is the same, even if the tools are different.

For all the techno-bells and whistles, some directors prefer to minimize the use of special effects. Husband and wife directing team Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris take a more contrarian approach. "People have seen so many special effects and been so wowed by them, that on some level I think they have lost their power," says Dayton. "To us, there's nothing more powerful than something that looks like you haven't used special effects."

That said, you would be hard-pressed to find a commercial director who doesn't agree that through the magic of digitalization and other postproduction processes they can now achieve what used to take days to shoot in real time. And even the biggest names in the business concede that convenience factor is hard to beat. Last year, veteran director Joe Pytka, who has won three DGA Awards and been nominated 14 times, digitally created the Budweiser Super Bowl commercial of a horse and dog high-fiving each other in five minutes using special effects. "If we had done it separately it would have taken all day," says Pytka. "It can really move a production along."

In directing Chevron's 2006 global "Human Energy" campaign, a series of ads shot in eight days over five countries, Pytka was able to capture the image of thousands of baby carriages rolling through myriad settings to represent the world's growing population and the strain it will place on energy sources through special effects in postproduction. "With CGI I can do things I couldn't do even do a few years ago and apply those solutions to problems," says Pytka.

Dektor, also a DGA Award winner, agrees. "The polish you can bring to your work with CGI is incredible. There was a time when I was such a purist in terms of the camera and filming. But when you grow into it, CGI is an exciting new part of our work.

Although making commercials is still a pricey venture, directors say digitalization has saved a lot of legwork and, consequently, money. Take shooting in Manhattan, for example. The borough is now mapped digitally so if a commercial calls for a flood of water rushing through the city, there's no need to start from scratch. "The digital information of Manhattan, including every window pane, has been put together by experts and it's there," says Cornell. "The ability to scan things [digitally] is all within our grasp."

For most directors, learning how to use CGI has been a necessity, and very few can ignore it. With ad revenues and budgets shrinking, competition for jobs has never been fiercer, so the more variety of techniques a director can offer a client, the better. It wasn't always like this. During the '90s, a torrent of money from dot-comers triggered profligacy in advertiser spending. "There were no limits on how absurd or crazy the ideas," recalls director Dante Ariola. "There was so much ad money the future seemed limitless." Cut to 10 years later and a more somber mood prevails as the threat of recession looms. "There are many directors out there and you just have to be that much better because so many people want a job," says Dektor, who won the DGA Award in 2000. Adds Ariola: "You have to constantly evolve."

Fugslig has spent the past five years learning how to use CGI and integrating it into his work in what has been tantamount to a stint in film school. In that time, he has experimented with his craft, making some commercials in CGI, others conventionally in camera and still others as hybrids, using both techniques. "I'm infatuated with CGI. It's the future," he says.

(Top to bottom) Joe Pytka; Jonathan Dayton & Valerie Faris; David

(Top to bottom) Joe Pytka; Jonathan Dayton & Valerie Faris; David

Cornell (Credits: Pytka/Digital Domain; Jim Fronha/Goodby;

FORM/D'Arcy Masius Benton and Bowles)

The new wave of special effects has surely affected how the job gets done. Having a special effects crew on hand is now a standard part of most jobs. Their part of the equation is written into budgets and planned for from the inception of a commercial. Special effects teams are now a staple for directors, most of whom have their favorite crews who they work with regularly. "Special effects people come onto the set and are part of the process of helping to realize the director's vision," says Cornell. "They're a part of the team as early as the wardrobe people, sometimes even earlier, long before any filming begins."

But not all directors are automatically jumping on the technology bandwagon. Many, like Pytka, believe the product should dictate how the commercial is done. Some directors use CGI and special effects sparingly, and still others prefer to direct spots that minimize the use of CGI or special effects. Dayton and Faris strive for a subtlety and seamlessness so whatever has been done in the editing room isn't visible to viewers. For a new series of ads they directed for the NBA finals, the duo filmed 40 NBA stars, two at a time, then used digitization on a split screen (half of each player's face) to give the appearance of morphing into one as they talk simultaneously about the spirit of basketball and competition. Although the technique has been around for years, Faris says it has been perfected over time. "By tracking the heads and lining them up in the computer we could make them move together, like choreography."

Dante Ariola opted for a simple, direct, relatively technology-free approach for a Nike ad he recently shot. Spending three weeks filming around the Chicago area where Michael Jordan grew up, the director traced the basketball star's early years, shooting the house where Jordan was raised, the basketball court where he shot hoops as a kid and his high school gym—no shortcuts or special effects. "We went through the actual work ethic Michael had put into it," says Ariola. "We saw the original twin beds in his bedroom. I'd never followed someone's life to that degree."

Director Tim Abshire says special effects help him capture a comedic quirkiness that has become his trademark. For a commercial for "Scrubbing Bubbles," Abshire had two actors dressed as household maids paratrooping into a backyard. In one scene, the maids were clinging to the ceiling of a bathroom, a la Tom Cruise in Mission Impossible, to capture an action-hero feeling. The women were connected to cables and in postproduction Abshire digitally removed the cables and used 3-D graphics to build a new ceiling and make it feel like a real bathroom. "If I use special effects, it's often a question of trying to make something look silly and odd," he says.

Emmy-nominated director Alison Maclean prefers character-driven stories in her commercials. Her ad "Text Talking," a spot for Cingular, features a mother and daughter fighting over text messaging. For her commercial "Tom & Jerry" for the utility PG&E, Maclean went into the director's bag of digital tricks to show a squirrel burrowing through a long hallway carpet running from the house cat—and causing a spike in energy use. Although Maclean hails from features and documentaries—her doc Kitchen Sink screened in competition at Cannes in 1989 and won five international awards—she likes the challenge of telling a story in 30 seconds.

For some directors, advances in lens systems and camera technology are also changing the way they work. The ability to take a well-exposed shot and give it any look they want offers new options—not to mention a lot less equipment to lug around. Cornell says he reduced the amount of gear by 10 cases on location for a series of spots for Choice Hotels "because I no longer use filtration the way I used to. It's been a general progression," he continues. "We've always had filters. But now it requires nothing more than a well-exposed image and using one of a million colors that can create an instant matte and affect the image in so many billions of ways. That has really changed things."

But whether a director goes low- or high-tech, one of the benefits of new technology is that their commercials can end up on the Internet or YouTube. No longer is a 30- or 60-second spot confined to the boundaries of a television screen—even a big-screen TV. Pytka's ads for NASCAR for Fox were strung together in a loop and downloaded on the Internet, and the director says he routinely directs extra footage for the Internet version. In a medium that has conventionally been limited to short form, he says he sometimes appreciates the freedom of going longer.

Yet for all the changes under way in making commercials, the basics remain the same for most directors, who aim for variety in their work and prefer not to be pigeonholed in any one style or genre. "It's important to not do one thing," says Ariola. "I'm not a technocrat. I'm more of a Luddite. I'm into the final result of using special effects but not so much into the excruciating technical detail of doing it."

Ultimately, the art of directing commercials resides in the talent and imagination of the men and women who know their craft and excel at it. At best, the results are the unforgettable ads that seem to leave an indelible imprint on the culture. They're the ones that TV viewers still talk about years later. Pytka, who is now working on a commercial for a new model of the Ford Acura, embraces many of the new technologies in his field but cautions that they can become a crutch for directors. "They work best if it can be a valuable tool," says Pytka. "But some directors rely on technology for the wrong reasons, because things the other way are too dangerous or seem impossible to do. New digital effects are incredible, as long as they're not abused."