BY GARY GIDDINS

(Credit: Criterion)

(Credit: Criterion)

If Ernst Lubitsch had been conceived with "the Lubitsch touch" he might have looked like Cary Grant, spoken like Herbert Marshall, and moved like Fred Astaire. No such luck: Maurice Chevalier, an actor virtually remade by that touch, recalled him as a "droll, cigar-smoking cherub"—a kinder description than many. Dark and dumpy, Lubitsch had piercing eyes and a smirk sufficiently ironclad to survive his omnipresent cigar. Renowned for directing large and small roles alike by precisely miming the desired gestures, he waddled when he walked and was thought to be generally clumsy.

Yet he invented a comprehensively detailed fantasyland occupied almost exclusively by adults, many of them attractive and sexually gifted, who glide stylishly through life, speaking softly and carrying a large repartee. As his characters make their way from one boudoir to another, balancing as best they can the distinction between seduction and love, romance and responsibility, we never feel that Lubitsch is envious or disapproving of his characters. If we could vacation in the films of any director, we might well choose his, if only for the clothes. As timeless as it is imaginary, Lubitsch's world is an outpost located somewhere between Ruritania and Hollywood, dotted with Epcot-like villages called Paris, Budapest, and Venice that are no more or less real than Sylvania—the setting for his first talkie,

The Love Parade (1929).

In that film, Chevalier's lusty soldier pretends to explain why his accent is so very Fraaanch, unlike that of other Sylvanians, as represented by the patrician Jeanette MacDonald (her film debut), the eccentric cockney dancer Lupino Lane, and the precocious Broadway babe Lillian Roth (all of 17). Chevalier's thoroughly facetious explanation is a rare acknowledgement of illogicality in an oeuvre that usually dispenses with rationalizations, apologies, or justifications of any kind. The central figures in Trouble in Paradise are a couple of thieves and their dupe; the leading men in Design for Living consent to a semi-chaste ménage à trios with the leading lady; the hero of Heaven Can Wait recounts to Satan stories of his unquenchable lust and is rejected from hell for having enjoyed life too much. Laughing well is the best revenge—and who's complaining?

But many did complain, never more vociferously than when Lubitsch unveiled his 1942 masterpiece, To Be or Not To Be, a near-slapstick romance set against the Nazi invasion of Poland and starring Jack Benny and Carole Lombard. Decades passed before film lovers could agree that this burlesque was, in its way, as trenchant as the usual depiction of goose-stepping monsters. Mockery and contempt aren't the least effective responses to absolute evil, and a Hitler who says "Heil myself" puts barbarity in perspective. Lubitsch was nothing if not a humanist—the pater familias in a pantheon that includes Jean Renoir, Leo McCarey, Yasujio Ozu, and few others.

Lubitsch, the son of a successful Berlin haberdasher, was born in 1892, and found his way to Max Reinhardt's theatrical company as a teenager, playing a hunchbacked carnival clown avenging the murder of a dancing girl in an Arabian harem pantomime. Over the next few years, he starred in several short films as the stereotypical Jewish schlemiel, invariably saving the day. In 1918, Lubitsch began to direct movies starring Pola Negri, combining melodrama, impish humor, and a sharp eye for the way cinematic storytelling proceeds from meticulous staging and rhythmic editing. Kino has issued splendid prints of several of these early films, including Sumurun, Lubitsch's adaptation of Reinhardt's harem ballet, reprising his role as the hunchback—his farewell to acting.

(Credit: AMPAS)

(Credit: AMPAS)

Kino's other titles are more indicative of his increasingly stylish and mocking social criticism: The Oyster Princess, Anna Boleyn, and especially The Doll, which opens with Lubitsch constructing a dollhouse that turns into the actual film set, just as the mechanical doll at the heart of the story becomes a genuine woman. In 1922, Mary Pickford brought "the European Griffith," as he was called, to Hollywood, though she fought with him while making Rosita. It hardly mattered: Lubitsch took to America like bratwurst to cabbage. Charming everyone but Pickford, from actors to studio heads, he set out to raise the bar for sophistication. From 1924 to 1928, he attained new heights in a series of silent romantic comedies that, as Renoir observed, reinvented Hollywood with continental panache. Among these films (presently unavailable on DVD), two of the most ingenious are adaptations of Oscar Wilde's epigrammatic play Lady Windermere's Fan and Sigmund Romberg's operetta The Student Prince, each enhanced with emotional truths in the absence of the factors—wry dialogue and chest-thumping songs—that made them famous.

In 1929, he embarked on a quartet of musicals for Paramount, recently collected in a Criterion DVD set: The Love Parade, Monte Carlo, The Smiling Lieutenant, and One Hour with You. If the first is the most static, it is also the most prescient. At a time when film musicals were inert revues, often with a single camera facing the proscenium, and songs were recorded live on the set, crippling movement and spontaneity, Lubitsch created a fluid, funny gambol in which songs emanate from the story. These four musicals and a fifth, The Merry Widow—made at MGM in 1934 and the most gracefully polished of all—track his growing command of sound. Even Monte Carlo, the weakest of the lot, thanks to Jack Buchanan's ineffectual giggling in the kind of role elsewhere allotted to Chevalier, has an enchanting scene as MacDonald sings "Beyond the Blue Horizon," looking from a train window, accompanied by the train's whistle and chugging rhythms.

Yet if Lubitsch showed that sound did not have to transform cinema from visual poetry into mere theatrical documentation, he also proved that the lessons of the silent era remained indispensable. The Lubitsch touch is exemplified in the opening episode of The Love Parade. We see a closed door and hear an argument. Chevalier walks through the door and addresses us directly: "She's terribly jealous." A woman enters after him, holding aloft a garter. She lifts her skirt to show her own garters in place, and then pulls from her purse a pistol. Suddenly, her husband bursts in, and she fires into her own chest. The distraught husband retrieves the pistol and fires at Chevalier, who, finding no holes in his body, gallantly attempts to help the husband, pointing out that the gun isn't loaded. They turn to the wife, watching them from a prone position. The husband is so relieved he forgets his anger and takes her home. Chevalier shrugs and drops the pistol in a desk drawer, which is filled with a dozen similar weapons. Virtually every shot, master or insert, adds to the joke and it is all played out in nearly complete silence.

In 1932, Lubitsch made his first non-musical talkie masterpiece, Trouble in Paradise (available from Criterion), which begins with another unforgettable silent bit, a garbage man hauling trash into a gondola—Lubitsch's way of telling us we are in Venice. Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins play thieves who fall in love while conning each other. They target a wealthy heiress played by the inimitably lisping Kay Francis: "You are vewy, vewy clever," she tells Marshall, who seduces her while we watch a clock for more than a minute, as time passes in successive dissolves, which lead to further clock-dominated episodes. When dialogue served no purpose, Lubitsch omitted it, shooting the characters through a window, speaking inaudibly. Watching Trouble in Paradise for the nth time, one continues to marvel at its clockwork precision.

(Credit: Photofest)

(Credit: Photofest)

Time seemed to be running out on Lubitsch's raillery, however, as Joseph Breen arrived in Hollywood to enforce the Production Code. Chevalier, who had originally become famous for a working-stiff persona until Lubitsch put him in a tuxedo, was shown the door along with Paramount's other erotic pinups, Mae West and Marlene Dietrich. In 1934, the studio promoted Lubitsch to production chief, a disastrous move as he could not keep from offering directorial help. One Hour with You began as a George Cukor project, until Lubitsch began shooting retakes, eventually taking control of the picture. A few years later, Lubitsch was reborn, his spine stiffened not only by the code but by personal and professional disillusionment—he discovered that his wife was having an affair with his longtime writing partner, Hanns Kräly, as his films (including The Merry Widow) died at the box office.

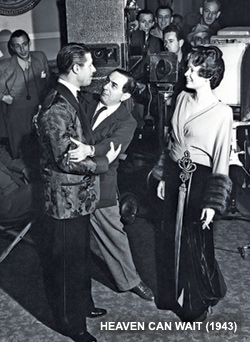

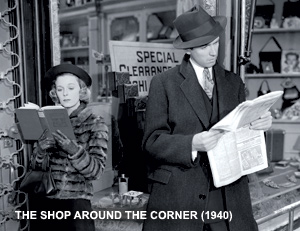

The years 1938-1943 were perhaps the richest in Lubitsch's career, and four of his most brilliant films are available on exceptional DVDs: Ninotchka and The Shop Around the Corner (made at MGM, now on Warner Bros. DVDs), To Be or Not To Be (made at United Artists, now a Warner Bros. DVD), and Heaven Can Wait (made at 20th Century Fox, now a Criterion DVD). Lubitsch's themes of romance between opposites, triangles, infidelity, and the deflation of pomposity remained dominant, but the vision had deepened—these films are funnier and more emotionally brittle.

Ninotchka (1939) was famously advertised with the tag, "Garbo Laughs!" Garbo had, in fact, laughed on screen before, but she had never elicited many laughs. As a dour Soviet envoy who says of Stalin's show trials, "There will be fewer and better Russians," she discloses subtleties of timing and timbre that are pure Garbo, yet unlike anything else she did before or after. Ninotchka endures as a nearly unique Hollywood take on the Soviet Union—a dark, knowing, yet humanistic satire, unlike the sentimental paeans made during the war or the fearful propaganda that followed. Billy Wilder, who co-wrote the screenplay, would attempt to recapture many of Lubitsch's conceits in later years, including his indulgent puncturing of Soviet agitprop (in his 1961 film, One, Two, Three), but the Lubitsch touch could not be transferred. As Wilder told Action!, the predecessor to the DGA Quarterly, in 1967, "If we were lucky, we sometimes managed a few feet of film... like Lubitsch, not real Lubitsch."

In To Be or Not To Be, the pursuit of a traitor determined to wipe out the entire Polish underground is centered on a theatrical troupe that, as one character notes, does to Shakespeare what Hitler is doing to Poland. Lubitsch generates suspense without neglecting sexual flirtations, beard-pulling pratfalls, and the inestimable vanity of Jack Benny's Hamlet. The marvelous character actor and Lubitsch favorite, Felix Bressart, stops the Nazis in their tracks by reciting the "Hath not a Jew eyes" speech from Merchant of Venice, not as Shylock would, but as if the lines had just occurred to him in the theater lobby. We don't know whether to laugh or cry.

(Credit: Photofest)

(Credit: Photofest)

Still, the most emotionally intricate of Lubitsch's films is The Shop Around the Corner (1940), in which James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan, at their peak, insult each other into a mighty love, while their boss, played by Frank Morgan in an uncharacteristic mood of distress, learns that his wife "didn't want to grow old with me." The cuckoldry here is painful, even embarrassing, yet it unfolds in a mist of inspired humor; the boss's failed suicide is treated as no more pressing than the disposal of the shop's reviled "Ochi Chornya" music boxes. Lubitsch favored life over death, but that's no reason to be inundated with the once ubiquitous Russian gypsy song. His own death in 1947, at 55, came much too soon. As Billy Wilder later told Action!, he left the funeral with William Wyler, commenting, "No more Lubitsch," to which Wyler responded, "Worse than that, no more Lubitsch pictures."