BY STEVE POND

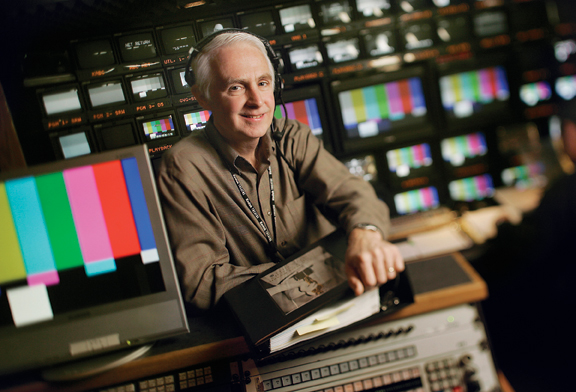

THE BEST LAID PLANS: Louis J. Horvitz, who has been directing the

THE BEST LAID PLANS: Louis J. Horvitz, who has been directing the

Oscars for 12 years, says "all you can do is prepare."

Even veteran Horvitz couldn't plan for an Oscar globe that stopped

spinning before the show. (© Greg Harbaugh/AMPAS)The actor stood bathed in a spotlight on the stage of the Shrine Auditorium, cradling a shiny gold Academy Award and beaming as he said his thank-yous. Behind the Shrine, in a high-tech truck that served as the telecast's nerve center, director Louis J. Horvitz watched closely, scanning the dozens of monitors in front of him. It was March 1997. This was the first Oscar to be handed out on the first Academy Awards show Horvitz had ever directed, and he knew he had to get it right.

So when the winner paused after 25 seconds, Horvitz shouted "Music!" cuing conductor Bill Conti's orchestra to play and usher the winner off before he got verbose and set the kind of precedent that could lead to an interminable evening.

But the guy standing onstage holding the little gold statuette was Cuba Gooding Jr., and he was far from finished. As the orchestra played louder, Gooding talked louder; he danced, he yelled, he threw his arms in the air, and he turned the fact that the orchestra was trying to drown him out into one of the classic Oscar moments.

In the truck, Horvitz could only laugh along with the audience, and along with producer Gil Cates, who'd hired him for the job. The moment may have made the director and producer seem a little trigger happy, but it sure made for good television. Here it was, the very first award on Horvitz's very first telecast, and the fates—"the Oscar gods," as Cates likes to call them—had conspired to deliver a message: "Welcome to the Academy Awards, rookie."

Ten years and 11 Oscar shows later, Horvitz shakes his head. "The first time Gil hired me, he said, 'Trust me, you have never been through anything like this before,'" he says. "And I have to say, he did not underestimate the whole proposition."

In a time when award shows have become a year-round staple on both network and cable television, when every organization, academy, critics group and sewing circle feels obligated to honor the best of the year, the Academy Awards are something different—for the audience who watches, for the filmmakers who compete, and definitely for the directing team who makes sure it runs as smoothly as a big, showy, $10 million-plus production built around movie stars can possibly run.

"We work on halftime at the Super Bowl, we do the Kennedy Center Honors, which the president attends—those are all things of big visibility," says Jim Tanker, Horvitz's 1st AD on 10 Oscar shows. "But the Oscars are special, because sociologists look at them through the years—the style of music, the style of dress, what the mood of the country was politically, which is often reflected in acceptance speeches. It's a living record of the time. And it's intimidating to think that what's leaving your truck is being seen by much of the world."

Dency Nelson, a stage manager on the verge of his 20th Oscar show, mans the stage-right wings from which presenters, performers and winners make their entrances and exits. He's seen hundreds of stars walk off dozens of stages cradling gold prizes of all sorts. "There is very little cynicism surrounding the Oscar," he says. "With some of the other awards, to some extent you see stars come offstage and treat them as just a trinket. Nobody treats the Oscar like a trinket."

For the last dozen years, the show has been the work of essentially the same team, which can consist of more than half a dozen associate directors handling cues in the command truck and twice that many stage managers inside the theater, where they oversee set changes, man the teleprompter and shepherd the host, the presenters and the performers both onstage and off. The crew is spearheaded by "Louis J.," as nearly everyone calls Horvitz. A film major at UCLA who started as a cameraman, Horvitz cut his teeth directing the music show Solid Gold, and then moved into live television with the Live Aid concert in 1986, followed by music specials (Paul Simon, the Rolling Stones), Super Bowl halftime shows and the Emmys.

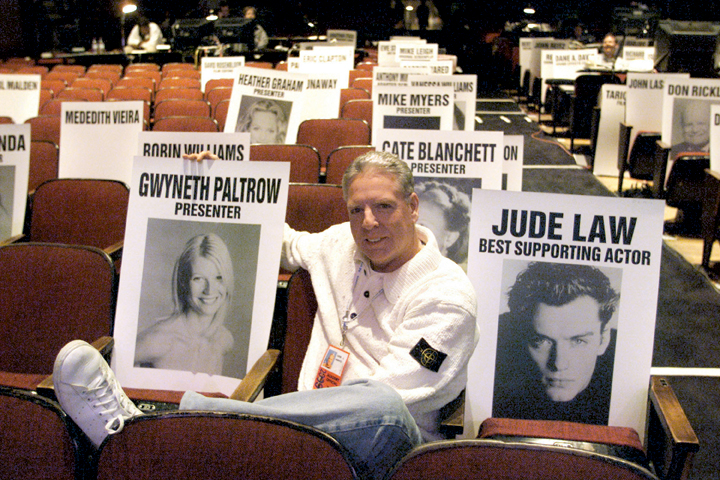

TEAMMATES: 1st AD Jim Tanker sits beside Hovitz during the show.

TEAMMATES: 1st AD Jim Tanker sits beside Hovitz during the show.

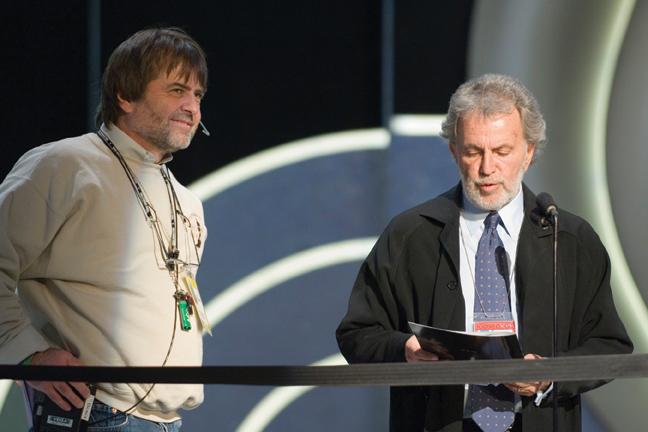

Stage Manager Dency Nelson with president of the Academy, Sid Ganis. (© AMPAS)"Lou knows exactly how to tell the story of the event," says Cates, who's currently producing his record 14th Oscar show and eighth with Horvitz. "That's the most important quality in a director of any live event: you've got to not keep your head in the book, but use those 15 or 20 cameras to see everything that's going on and make the people at home feel as if they're there." Cates collaborates closely with the director in the months leading up to the show, then sits behind him in the truck during the broadcast. "Lou is sensitive to the politics of show business, as well as the technical side of shooting a show like this one," adds Cates. "At the moment, I think he's without peer."

"I think being a cameraman really helped him as a director, because he sees things that other directors may not," says stage manager Garry Hood, whose Oscar tenure dates back to the mid-'80s, where he mans the stage-left wings and has special responsibility for the show's host. "He has a vision before we ever get on camera. We'll be working on the model of the set, and he'll bring in a little video camera, move things around and know exactly how it's gonna work. That still blows me away."

A perfectionist who admits that he used to stress about live shows so much that he wound up in therapy over it, Horvitz makes no bones about the fact that he demands the best from his team. ("Lou has got an exotic personality," says Cates with a laugh.) "There's no getting around it, he's a tough taskmaster," says Nelson. "But Lou brings the live awards show up to feature-film status in my mind."

To do that, Horvitz says, requires planning and preproduction on a near-feature level. He starts in the fall, reviewing past shows with the producer (usually Cates, though he's also worked with the likes of Laura Ziskin and Richard and Lili Zanuck), going over the look of the show with the set designer and lighting director (usually Roy Christopher and Bob Dickinson), and awaiting the first moment of truth: the late-January unveiling of the nominations, which tells him what films will be in play, what actors are liable to attend, and what songs he'll be showcasing on the program. "That's a magic moment," Horvitz says of the 5:30 a.m. announcement, which he also directs. "And it can also be the most challenging aspect of the show, when they hand you those five musical acts that you have to put in there."

As the show nears, Horvitz meticulously marks his script with every cue for each award: scenery cues, music cues, announcer cues, video screen cues and graphics cues and many more. Sometimes (well, rarely) it's straightforward; oftentimes, such as the show in 2000 when video and graphics were presented on several huge, multi-screen towers rolled on and off the stage, it can be a nightmare. "I started writing my cues that year," he says, laughing. "You know: 'Roll A, big monitors, second tower, C portion of the tower, roll B...' By the time I finished marking down the cues, the page was littered and there was no room to write anything else. And I thought, my God, what have I done? I'm going to have to call this for 26 awards."

Since the move to the Kodak Theatre in 2002, Horvitz has controlled the telecast from a truck parked at the theater's loading dock. Sequestered in the truck with several ADs and a handful of tech staffers and executives, Horvitz keeps an eye on the meticulous plan detailed in his script, which maps out each shot for every entrance, award and production number. But he's also constantly scanning the monitors that show what each of the nearly two-dozen cameras is shooting, so he knows where to go for an unexpected angle or especially a good reaction shot.

"With every potential winner, he has to know if their significant others are out there," says Tanker, who sits beside Horvitz during the show and handles many voiceover, music and commercial cues himself. "And it's very hard on the cameramen. If nominee A wins, then the cameramen assigned to B, C and D have to flank over and get somebody else, because that's going to help tell the story of person A. Multiply that times five nominees times however many awards there are, and they have a very full playbook. And they need to immediately get the pictures, because if you wait a few seconds the moment's gone. But I've never seen anybody with a faster scan than Lou. He can have 20 or 30 cameras, but he seems to just see everything."

The director calls out every cut, cues the cameraman on who's up next, and talks on his headset to the stage managers inside the Kodak to signal each star entrance or change of scenery. He gets constant updates on which stars have headed for the bar and won't be available for reaction shots, or which set changes are taking longer than expected. During the show, moments of levity or celebration on stage serve as brief respites inside the truck in a tense struggle to make the show seamless—a nearly impossible task, given the number of things that can go wrong.

"All you can do is prepare as much as you possibly can," says Horvitz. "You have to prepare for the what-ifs. What if this happens? What are our options? What if you lose your teleprompter, or you lose the two center cameras? Well, then you hand [the star] a script and they go out there and talk to the Steadicam."

In other words, you can't fix it in post, so you'd better be ready to roll with whatever the Oscar gods throw your way, from a winner who won't shut up to an actress who tells you 10 minutes before her entrance that she'd really rather not walk down that majestic staircase you've got all ready for her.

That last scenario happened with Julia Roberts in 2004, and Horvitz did what he had to do: he gritted his teeth and ordered the crew to remove the stairs and close a curtain, so that Roberts could enter from the wings and go straight up a ramp to the nearest podium. Then he tried not to dwell on the fact that the last presenter, Oprah Winfrey, had made the exact same entrance.

TOP GUNS: When producer Gil Cates (right) hired Horvitz, he told him "Trust

TOP GUNS: When producer Gil Cates (right) hired Horvitz, he told him "Trust

me-you've never been through anything like this."Horvitz can happily detail a decade's worth of audibles, mid-show changes and close calls:

For the 75th Oscar show in 2003, designer Roy Christopher hung a huge spinning globe, encircled by the words "OSCAR 75," over the stage. The globe slowly spun all during rehearsals, and Horvitz had planned to make it the show's signature look—until, with less than five minutes to airtime, it stopped spinning. The technician sent onto a catwalk above the stage to try to fix the problem only made things worse. He couldn't get to the globe, but he did manage to drop his walkie-talkie onto the stage during Steve Martin's opening monologue. Horvitz, meanwhile, quickly called up shots of the spinning globe taken during rehearsals, and used those as bumpers.

Michael Flatley, the self-proclaimed "Lord of the Dance," came into the truck just before the show in 1997 and told Horvitz that the onstage cameraman should be coming in for tighter shots: "Don't worry about me, just get that camera in there," he said. Horvitz obliged, ordering cameraman Hector Ramirez to go in tighter and tighter, right up to the moment when Ramirez got so close that Flatley danced smack into the camera. "I'm thinking, oh hell, I knocked out the lead dancer with my camera. I'm done," says Horvitz, who used a wide shot to give the "Lord" time to recover his footing.

The rock band Aerosmith likewise asked for more pop when they performed their nominated song from Armageddon in 1999. The song included a moment when lighting designer Dickinson cued several propane torches to go off, and the torches just weren't impressive enough during rehearsal. So Horvitz urged Dickinson to turn them up—and then watched, aghast, as jets of flame climbed so high that, he says, "I really thought it was going to burn the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion down."

Louis J. is not complaining about any of this, mind you. "I won't lie about it: as much as I angst over it, it's a thrill," he says. "You're challenging yourself to do your recital and not make any mistakes; you're challenging yourself to play in the Super Bowl and win."

His only regret, he adds, is that sometimes he feels as if he's stuck in that truck, watching from a distance while history is made a few feet away. "I do realize that for years, I've missed the energy of that live room at so many great moments," he says. "There's nothing like the kinetic energy of the room. Particularly for things like the year Elia Kazan got his honorary Oscar, which was so controversial. I'm proud of the way Gil and I covered that event—but while that was happening, I would have liked to have been in that room. I mean, no matter how I direct it, there's nothing I can do that will give you the actual experience of being there."

Horvitz will be there again in February 2008 for the 80th Oscars. As he talks about the upcoming show, planning is just starting in earnest, and even the names of the nominees won't be revealed for a few more weeks. And yet, Horvitz can feel that big show approaching.

"It's easy to sit here and talk about the past shows," he says, grinning as he thinks of the task ahead of him. "But even as I talk about it, I'm already starting to get butterflies."