BY GARY GIDDINS

(Credit: Kino Video)

(Credit: Kino Video)

During the past several years, film noir has become the preferred genre in movie publishing and DVD releases. I count well over 50 volumes on the subject, a number that indicates the diminishing returns to be found on bookshelves buckling under encyclopedias and anthologies of film noir essays, publicity stills, poster art, and quotable dialogue; not to mention tomes on film noir directors, writers, composers, cameramen, and actors—with particular attention to those who played femmes fatales. Meanwhile, DVD companies release whatever suitable movies they own, along with some that aren't so suitable, because film noir is more than a genre: It's a marketing tool for the mostly black-and-white urban thrillers of the 1940s and 1950s; it provides a veneer of cerebral approval when such native phrases as crime films or gangster films no longer do the trick. Thus we have Warner noir, Fox noir, MGM noir, Criterion noir, and Hammer Noir (from the English horror studio).

This enthusiasm is partly a French thing—representing an amour fou for movies with stylish mise-en-scène by directorial auteurs. Yet unlike Westerns, musicals, science fiction, and every other genre, film noir didn't exist as a banner in the years it peaked as a style. As a result, many elements that have come to characterize film noir—high-contrast chiaroscuro lighting, expressionistic staging, hard-boiled stories set deep in the underworld, location settings, themes involving sexual betrayal and innocence undone—evolved in a more competitive than formulaic environment, as filmmakers attempted to outdo each other in the relatively unmonitored world of low-budget second features.

French film critics coined the term film noir to denote the similarities between Hollywood's 1940s wave of brutal crime films and the pulp fiction that had appeared in France under the rubric, "Serie Noire." Yet not until the 1970s did American film critics and filmmakers begin to fetishize the style, which, at its best, produced imaginative, fast-moving, disturbing films, fraught with incidents and ideas that challenged the production code. In addition, they proved to be a testing ground or preferred idiom for filmmakers who later emerged as A-picture directors or cult figures, among them John Huston, Fred Zinnemann, Billy Wilder, Anthony Mann, Robert Wise, André De Toth, Jules Dassin, Sam Fuller, Richard Fleischer, Otto Preminger, Joseph Lewis, and Nicholas Ray. The excitement of rediscovering these films was intensified by the fact that they had initially received little critical attention. In the 1970s, postwar film noir was still practically a virgin field.

Kino, a company best known for distributing arcane international titles and refurbishing dozens of silent films, including the Edison archive and many masterpieces by D.W. Griffith, Buster Keaton, Fritz Lang, and F.W. Murnau, has long poked around in the noir field. Now it has packaged 10 films in two collections that define the phrase loosely enough to include movies that range beyond the confines of American crime, suggesting hyphenated genres such as propaganda-noir, current events-noir, British-noir, and even romance-noir. These are bare-bone discs, with hardly any extras—not even closed captioning—but the prints are solid and the selection is intriguing if not entirely first-rate. Film Noir: The Dark Side of Hollywood, released in 2006, includes Hangmen Also Die, Railroaded, The Long Night, Behind Locked Doors, and Sudden Fear. Film Noir: Five Classics from the Studio Vaults, released in 2007, has Contraband, Scarlet Street, Strange Impersonation, They Made Me a Fugitive, and The Hitch-Hiker.

The only directors represented with one film in each set are Fritz Lang and Anthony Mann. Lang made a dozen Hollywood pictures that could be defined as classic noir. Hangmen Also Die! (1943) is not one of them. It was a fictional attempt, scripted by Bertolt Brecht, to recreate the 1942 assassination of the Nazi butcher Reinhard Heydrich and the unspeakable reprisals that followed, which eradicated the town and population of Lidice. (Douglas Sirk's Hitler's Madman, also from 1943, was based on the same incident.) No contemporary film, let alone one starring Brian Donlevy as the Czech hero, could have lived up to those events, but Lang's picture has aged well. Photographed with glistening precision by James Wong Howe and scored by Hanns Eisler, it recalls his early serial-like German pictures in which plot is unfolded in layers and nothing is as it seems. As such, it offers a stylistic link between the expressionist pulp Lang helped to invent and medium-budget Hollywood successors, including Lang's sublimely perverse Scarlet Street (1945).

Kino located a near-pristine print of Scarlet Street in the Library of Congress, and it exemplifies Lang's fastidious control of studio stages. He and photographer Milton Krasner invented a sordid stand-in for Greenwich Village, painting the night with an inky blackness and reflective glare. A matchless study of male midlife crisis born of missed opportunities, Scarlet Street also packs a nasty if droll rabbit punch on the subject of art and authorship. It was Lang's follow-up to his hit, The Woman in the Window (now an MGM noir), constructed like its predecessor around an impulsive murder committed by milquetoast Edward G. Robinson who is caught in a web spun by cellophane-wrapped streetwalker Joan Bennett ("You are clever," she tells him when he guesses that she must be an actress) and pomaded pimp Dan Duryea (whose catchphrase is "For cat's sake").

(Credit: Kino Video)

(Credit: Kino Video)

Mann is similarly represented by an anomaly and a classic noir. The former is the little-known Strange Impersonation (1946), a 68-minute, stylistic tour de force about a woman scientist who rebuffs her fiancé in favor of her self-experimentation with an anesthetic. She pays the price by losing her face, her personality, her fiancé, and very nearly—and on more than one occasion—her life. Of course, the whole story is a dream, but unlike other dream movies, including The Woman in the Window, Mann doesn't pretend to hide it. The film's style becomes more radical as the plot becomes more preposterous. Yet at heart, it remains a woman's picture in which the femme fatale haunts another woman—the fiancé is a worm who doesn't even get the chance to turn.

By contrast, Railroaded (1947) is quintessential postwar noir and Mann's breakthrough as a hard-boiled observer of criminal sociopaths. Jane Randolph plays the operator of a beauty parlor that doubles as a bookie joint; her paramour, John Ireland, is a vicious thug who meticulously perfumes his bullets and massages his gun barrel. When she arranges for him to rob her betting parlor, everything goes haywire. Mann pulls out all the stops—staging a brunette-on-blonde catfight under Ireland's bemused gaze, and shooting the syndicate boss's office as a tableau of deep shadows, glaring table lamps, and the unexpected touch of bountiful bookshelves. He is equally deft at contrasting the dark relationship between Randolph and Ireland with a cop's daylight courting of a good girl, and he subtly incorporates the recent war as part of the background to social dissolution.

(Credit: Kino Video)

(Credit: Kino Video)

Postwar noir was obsessed with documenting the psychological depression that followed so quickly on the heels of victory. Despite the GI Bill, affordable housing, the spread of suburbia, and the middle-class fantasies perpetuated by that recent invention television, the bottom half of double features countered the piety and affluence of cinemascope spectacles with a vision of America beset by ennui, hysteria, and guilt. Two of the Kino selections document a similar decline in morale in England. Michael Powell's Contraband (1940) features the first star of German expressionism, Conrad Veidt, as a Danish sea captain who has to navigate the cellars of Soho, amid Blitz blackouts, to foil a spy ring. He prevails, but London is clearly at sea. Alberto Cavalcanti's superior They Made Me a Fugitive (1947), featuring a gripping performance by Trevor Howard, also descends into the underground, but the spies have been replaced by organized crime, the blackouts by the black market, and a heroic ship captain by an unemployed, victimized war hero.

Dislocation and desperation characterize the remaining films. In the semi-noirish The Long Night (1947), Anatole Litvak's unnecessary remake of Marcel Carné's Le Jour se léve, the narrative structure is splintered, as the recollections of one night give way to flashbacks within flashbacks—a strange movie convention of the period, also explored in Passage to Marseille and The Locket. Budd Boetticher's Behind Locked Doors (1948) is a minor programmer, interesting as a prophetic examination of the fear of madness, as a detective goes undercover in an asylum—the plot device later used by the Swiss novelist Friedrich Dürrenmatt in The Quarry and by Sam Fuller in Shock Corridor. The dialog is unintentionally hilarious: "I've told you a dozen times not to abuse the patients!"

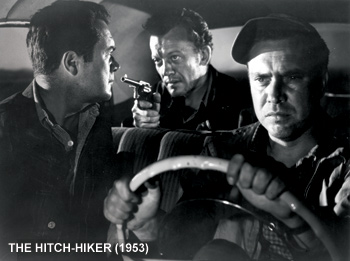

Far better are the two 1950s films. In David Miller's Sudden Fear (1952), Joan Crawford suffers the penalties of female success while tormentor Jack Palance is undone by the latest in fear-inducing technology: secret recording devices. In Ida Lupino's nail-biting triumph, The Hitch-Hiker, a malevolent William Talman turns American's ribbon of highway into a hell on wheels. Lupino, a cult figure twice over as actor and director, is overdue for DVD resurrection. The half-dozen films she directed from 1949 to 1953 consistently tackled controversial themes from a woman's perspective: unmarried mothers (Not Wanted), rape (Outrage), women's sports (Hard, Fast and Beautiful), debilitating illness (Never Fear), and bigamy (The Bigamist). Yet her most effective film, The Hitch-Hiker, is a testosterone-heavy exploration of what two ordinary guys (you can't get more ordinary than Frank Lovejoy and Edmond O'Brien) discover themselves capable of under threat from a psychopath. Lupino maintains the suspense at fever pitch.

The noir revival of the 1970s and 1980s produced several savory films, including at least one undeniable masterpiece, Roman Polanski's Chinatown (1974, available in a sparkling new transfer from Paramount). But most of them were stylistically and thematically self-conscious, as they attempted to revive the attitude and look of the classic noirs or, as in Chinatown, set the story in the perilous past. What makes the Kino selections so mesmerizing is the conviction with which they reflect a terrifying present.