BY STEVE POND

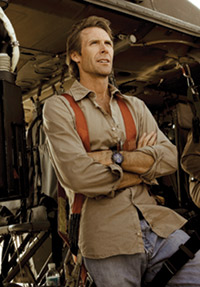

THE FAST LINE: In staging action, Michael Bay starts with a couple key shots.

THE FAST LINE: In staging action, Michael Bay starts with a couple key shots.

For Transformers he knew he wanted a robot that looked like a hockey player

coming down the turnpike. (Photo Credit: DreamWorks, LLC/Paramount)

Recreate the Trojan War? No problem. Catapult a car into the air to destroy a helicopter? All in a day's work. Detonate a Venice mansion and watch it crumble into the canal on which it sits? Piece of cake. These are the tasks routinely faced by the directors of action films, those supercharged thrill rides that pack the multiplexes every summer—and, quite often, the rest of the year as well. It's a genre where the budgets tend to be big, and so are the expectations. And it's a genre where, to be truly successful, a film must simultaneously involve its audience, move it, and then blow it away.

"When you're directing an action film," says Mimi Leder (The Peacemaker and the upcoming The Code), one of the few women to have tackled the job, "you need to ask yourself a few questions: Why is the character going from A to B? How is he going to get there? And how is he going to get there in the most exciting, powerful, kick-ass way possible?"

So how do these directors pull it off? Ask a cross-section of those who've worked in the genre, most of them unabashed fans of action films both old (Bullitt, Raiders of the Lost Ark) and new (The Bourne Ultimatum, Casino Royale), and you'll get a wide range of responses. Michael Bay, whose resume stretches from The Rock and Armageddon to Transformers, recommends keeping your own energy high to set a tone. Wolfgang Petersen (Troy, Air Force One) says the key is not the fights or explosions, but the suspense and tension you can create within the action. Richard Donner (Superman, Superman II and the Lethal Weapon films) warns that you don't need to take risks on the set, because you can create what you need in the editing room.

And everybody agrees that it all starts with knowing exactly what you're going to do before you do it. "The main thing is preparation, preparation, preparation," says Michael Davis, a former animator and storyboard artist who drew all the crucial sequences in his recent film Shoot 'Em Up by hand. "Well before we started shooting, we had what we call 'school.' Every day we'd take a scene and go over every little thing with the stunt guys, the AD, the camera department, the production designer. How does this prop work? Where do the legs of the table have to be broken? How big do the sparks have to be? Where do we place the sparks? If you can answer all those questions earlier rather than later, things will go a lot smoother on the set."

(Photo Credit: Phil Bray/Paramount Pictures)

(Photo Credit: Phil Bray/Paramount Pictures)

Bay starts with a blank canvas; he asks screenwriters to simply put "Action" at appropriate points in the script, and then works out what that action will be. He starts by storyboarding and making animatics, computer-drawn storyboards with full movement. He does these not for the entire film, but for what he considers the seminal sequences—signature moments that will stand out and define the movie, such as the shot in Pearl Harbor that follows a Japanese bomb as it falls onto the USS Arizona. "You start with a couple of key shots, and I will work with my animatics team very early on to create those shots," he says. "Like on Transformers, I knew I wanted a robot to look like a hockey player coming down the turnpike swiping cars, and I knew I wanted it to look like two football players tackling each other."

The stunt coordinator is crucial, as is the second unit director (and they're often the same person). So is the first AD, the visual effects coordinator, the cinematographer, the editor... "The most important thing is to hire yourself a great stunt arranger, then hire yourself a terrific second unit director, then get all the credit," jokes Casino Royale director Martin Campbell. "That's not true, but these things are definitely a team effort. There are a lot of unsung heroes on these films."

The director maps out what he wants, sets the tone, works with the actors. But often as not, the portions of the action sequences that don't involve the lead actors are shot by the second unit. "In meetings and preproduction, you map out what the overall feel of big action scenes, and the look of it and the feel of it and the drama of it," says Petersen. "That, actually, is the fun part. But I don't just tell my second unit, 'This is what I want.' It's really a dialogue. These top guys are very much part of the creative process. For example, [second unit director] Simon Crane came up with that whole thing in Troy of the Trojans rolling fireballs down to the beach. In good cases, it's very collaborative, creative work with these guys."

Sometimes, actors can be part of the creative team, too. Brett Ratner, director of the Rush Hour films, credits Jackie Chan with not only performing but also designing many of the stunts in those action comedies. Jet Li, Harrison Ford and Mel Gibson also win kudos from directors for their active participation. Sometimes, in fact, they err on the side of too much participation: Donner says he was "ready to kill" Gibson for swapping places with a motorcycle-riding stuntman behind the director's back during the filming of one Lethal Weapon chase scene.

And then there are the actors who can be a touch reluctant. Although the basic rule is to use stuntmen if there's any danger to the actors, Petersen remembers being amazed when some of his cast members on The Perfect Storm balked at being lashed by man-made waves. "I said, 'Why not? The only thing is that you'll get wet!'" And Bay says he had to use an example from reality TV to shame his young Transformers star into doing one stunt. "We had a scene with Shia LaBeouf hanging off a 20-story building on the edge of a statue. My producer said, 'Mike, we'll do this bluescreen, right?' I said, 'No way, we're not doing bluescreen! We'll hang him up there.' Now, there's no way you would ever get me to step out on that ledge, but this kid, he was 20. And I'm the director, so he'll do what I say. But right before he was supposed to do it Shia said, 'I can't get up there.' So I had to be, like, the tough coach, and I said, 'Are you a wimp? The kids on Fear Factor do this, and you get paid way more than them! Get up there!'"

Once the planning is done and the team in place, nearly every director has examples of scenes they never thought they'd be able to pull off. For Ratner, it was the climax of Rush Hour 3, an acrobatic fight that took place on the Eiffel Tower. "I never dreamed that I could do a scene using that much of the Eiffel Tower," he says. "When I looked at the movies that had been shot there, like the James Bond movie View to a Kill, they were just running up and down the stairs shooting at each other. We wanted to do things on the outside of the tower, inside the tower. For instance, the elevator shaft. I never thought they were going to give me permission to have Jackie Chan jump inside the elevator shaft and grab on to one of the moving cables to take him up. It was phenomenal that we were able to figure out how to do it safely, how to get camera positions, but also keep the camera out of the way of the moving elevator.

"And of course we couldn't use the entire Eiffel Tower, so we had to build a section of the Eiffel Tower and raised it high enough off the ground that we had depth, which meant we also had to rig all the actors and crew in wires. When you see the movie, you look in one direction, it's the real Eiffel Tower. You look in the other direction, it's a stage in L.A."

ROUGH SEAS: Wolfgang Petersen (with George Clooney on The Perfect

ROUGH SEAS: Wolfgang Petersen (with George Clooney on The Perfect

Storm) tries to create suspense and tension. (Photo Credit: Warner Bros)

When Wolfgang Petersen recalls a sequence he didn't think he could accomplish, he thinks not of special effects but of a simple, brutal, physical solution to a problem in Das Boot, his 1981 film set in a German World War II submarine. "I wanted to do the depth-charge attack as realistic as possible," he says. "And I had no idea how to do it. You can't just go and say, 'Okay, mime everything and we'll shake the camera,' in good old TV style. That doesn't work. So there were many sleepless nights over how to get that across to an audience, so that they really feel in their bones how the depth charges go off in this claustrophobic environment.

"And the result, finally, was that we put the control room of the boat onto a gimbal, which could shake the boat very violently. And then I had special effects people riding on the outside, banging huge sledgehammers against the metal. It was the most terrifying sound effect you can imagine. We had various cameras shooting the faces of the actors, and the terror on their faces was quite real."

The toughest sequences aren't always the biggest ones, though. Bay says one of the most difficult action scenes he's ever done was a close-quarters gunfight between Will Smith and a heavily armed street gang in Bad Boys II. The entire scene took place in a single room, so Bay laid a 25-foot circular track around the outside of the room, equipped a dolly grip with a motorcycle helmet and protective gear, and then had him run through the action pushing a small dolly topped by a remote-controlled camera.

In Troy, says Petersen, the trickiest scene was probably the climactic fight between Achilles and Hector (Brad Pitt and Eric Bana)—almost 10 minutes of two-man combat near the end of a movie that had been filled with enormous war scenes. "The big battles with the 10,000, you have your few hundred real people do the fight, and then CG takes over," he says. "But here, there is no CG, just those two guys—and in our case, not even stunt guys. That was a process that took about a year. The stunt coordinators worked on a style and a structure for this fight, and came to me with videos. We checked it and changed it, and it came finally to a form that we said, 'That's the fight that we want to do.' But we shot it maybe a year later, because the actors needed months and months and months to train." The only special effect was lengthening Pitt and Bana's swords in postproduction to make their near misses look more dangerous.

Richard Donner remembers a similarly lengthy process in planning the climactic sequence in the first Lethal Weapon. His stunt coordinator had worked with various martial arts experts to design a vicious fistfight between Mel Gibson and Gary Busey, who painstakingly rehearsed the elaborately choreographed action. "And the minute we started shooting the fight, it seemed Gary and Mel totally forgot every stunt, everything that was coordinated," Donner says. "These guys fought from instinct, and you could have thrown away that entire planning process."

In other words, the emphasis may be on preparation rather than improvisation, but that doesn't mean an action director won't need to do some of the latter as well. Donner also remembers an earlier instance, in 1976, when he had to scrap a planned stunt on The Omen on one day's notice because actress Lee Remick refused to wear a harness and hang from a crane. The new sequence, which involved dropping a fish tank in slow motion, then tipping the entire set on its side and having Remick stand on a dolly, wound up being one of the most celebrated scenes in the film. "I think it turned out better than my original idea," Donner concedes. "Those things happen, and you've got to be ready."

(Top) Richard Donner, directing Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon.

(Top) Richard Donner, directing Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon.

(Bottom)

Mimi Leder's The Peacemaker (Credit: DreamWorks LLC)

For Leder, it happened on location with The Peacemaker. "During an action sequence on a train, I was doing one shot on a Technocrane, where I follow this soldier up a ladder, out of the top of the train," she says. "The crane went over his head, and you saw that you were actually on a moving train. I did the shot, and then I did it again, and the second time we hit a wire. There were supposed to be no wires on the railroad where we were traveling, but there was a wire over the track, and it decapitated the camera off the Techno-crane and onto the floor of the train car where we were. No one was hurt, but it was a very frightening moment. And at that instant, I decided that it was no longer safe to do these shots on this moving train. So I changed my whole approach to shooting the sequence. I used more CG and shot a lot more plates than I had originally planned. And when you look at that sequence, you'll see a lot of live action and you'll see a lot of CG, but hopefully you won't be able to tell the difference."

These days, that's essential. Computer-generated imagery has evolved to the point where the interface between live action and CG should be invisible. Effects that are now routine wouldn't have been feasible 20 or 30 years ago—when, remembers Donner, he filmed the flying scenes in Superman on a front-projection stage and saw the results at dailies the next morning. If an effect worked, the crew cheered. The sense of instant gratification is gone, but the possibilities are limitless. In Bad Boys II, Michael Bay dropped real cars off the back of a car carrier moving down the highway at full speed, then added a CG Ferrari that dodged and darted through the falling vehicles. "There's simply nothing you can't do," says Martin Campbell.

The goal, say all the directors, is to come up with that effect, that scene, that sequence that's never been done before. Every action director wants to up the ante, to set the bar higher, to do a stunt that'll jolt even the most jaded audience. For Michael Davis, for instance, Shoot 'Em Up provided an opportunity to take things to new extremes. In the first few minutes of the film, Clive Owen's character delivers a baby in the midst of a shootout, cutting the umbilical cord with a gunshot before dispatching a few more foes. He subsequently has one gunfight in the middle of a sex scene, another in midair. The use of props seems inspired partially by old James Bond movies, but just as much by Buster Keaton and the Roadrunner. "There's this joyous quality to it," Davis says of his affectionate homage to the form, "because I'm getting to play with all the things I loved as an action fan as a kid, and just got to amp them way up."

For Campbell, the joy of Casino Royale was the opposite—the ability to take James Bond in a new direction by going for realism rather than excess. The goal was to ground the Bond films, which had gotten carried away with the kind of increasingly outlandish stunts that Campbell himself was familiar with from having directed GoldenEye almost a dozen years earlier.

"If you look at the action scenes in GoldenEye, what idiot would try to jump off a 2,000-foot cliff and try to catch a plane?" he says. "That's pure Old Bond, isn't it? It's enjoyable, but to be quite frank, it's not very real. And the point about Casino was to be more realistic than previous Bond films. Bond has been a magical recipe for so many years that we had to still keep the Bond ingredient in there—but the action had to give the impression of being much more realistic than previous Bonds. And the character was a rather rough-edged Bond. He wasn't in any way the James Bond of previous movies, which gave us some latitude."

In the end, agrees Bay, the job of an action director is to find that thing that hasn't been seen before, and then figure out a way to get it onscreen. "I always talk to my stunt coordinator and say, 'What haven't we done? What's new and different that we can do?'" he says, mentioning the scene from Transformers in which a group of U.S. servicemen in the desert are attacked by a giant scorpion-shaped robot. "I try to take things that I have in the back of my head. I always remembered a story I heard from SEALs in Grenada who were trapped, and they had no way to get air support except by calling the Pentagon, but they needed to find a credit card to make the call. So I used that in the scene where the Scorponox attacks the guys in the sand in Qatar. I loved combining that absurd, humorous moment with the chaos of this large-scale action scene. It's always about finding something cool, something new and different."

And make no mistake, Bay—and probably some others of his ilk as well—will be looking for that kind of idea not just in movie scripts, but in daily life as well. "Being an action director sometimes affects me in my personal life," he says. "I'll be driving down the road, and I'll pass some big truck or something and think, that looks dangerous. I wonder what could go wrong?" He laughs. "And suddenly, in my head, in the middle of the road, I'll go into this whole big action scene."