BY ROB FELD

TRADITIONALIST: The Treasure of the Sierra

TRADITIONALIST: The Treasure of the Sierra

Madre is the kind of film Paul Thomas

Anderson wants to make. (© Columbia)

"This feels so decadent, watching a movie in the middle of the day," Paul Thomas Anderson says as we drop into easy chairs in the screening room of the DGA's New York office to watch John Huston's 1948 classic,

The Treasure of Sierra Madre. "I haven't done this in years." Anderson is in New York on vacation after completing his first feature since 2002,

There Will Be Blood, loosely adapted from Upton Sinclair's 1927 novel

Oil! "When I watch this again, all of life's questions and answers are there in the movie; the way to make movies, live your life, get along, everything."

On the face of it, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre would seem an odd choice for Anderson whose own films, Boogie Nights and Magnolia among them, are sprawling, Altmanesque canvases with multiple, parallel stories. But he saw Sierra Madre as a kid and rediscovered it seven or eight years ago when he began to adapt There Will Be Blood.

"I was trying to find something that was 100 percent straightforward, old-fashioned storytelling," Anderson says as the titles roll over the grand, dramatic score by Max Steiner. "I definitely tried to mimic that approach. My natural instincts as a writer may be more scattered, so in an effort to be more traditional I used a book, just like they did. Sierra Madre is as direct as you can get—nothing clever, nothing structurally new or different—and I mean that as a high compliment. It's harder than anything else to be completely straightforward."

Anderson recalls that when he was younger he would teach himself to write by writing down scenes from films in order to see what they looked like on the page. "The films I love the most are, for the most part, very traditional in their structure. So, when I was getting ready to make There Will Be Blood, I put on Sierra Madre before going to sleep at night for a week, just trying to get it to soak into my head and help me approach storytelling in a more old-fashioned way. I suppose I kept looking at it as a film I wished I knew how to make."

Based on a novel by the elusive writer B. Traven, Huston's film follows Humphrey Bogart and Tim Holt as two American down-and-outers, scraping for cigarette money in 1925 Tampico, Mexico. They hook up with grizzled old prospector Walter Huston and embark on an ill-fated gold expedition, where all will eventually be lost to greed. The fact that Huston the younger directs his father in the film and shot on location in Mexico adds verisimilitude to the film, which excites and inspires Anderson.

FRIENDS FOR LIFE: As the three partners make a deal, Huston

FRIENDS FOR LIFE: As the three partners make a deal, Huston

set up the scene so he could flip the camera 180 degrees and

get a reverse shot on their handshake as Walter Huston

looks on skeptically. (Screenpulls: © Warner Bros)

"The way that I heard the story, Huston had to gently ask his dad to take his teeth out to play the part," Anderson recounts. "That's the benefit of working with somebody you know. You have enough time beforehand to plant an idea, because their first reaction is probably, 'No way, I'm not taking my teeth out!' But then they can mull it over. It's such a tough thing, your vanity. As an actor you have to think about what would be best for the film. That's the benefit of getting your father to play a part."

Sierra Madre opens with Bogart tearing up a losing lottery ticket on a dusty street, but soon reveals the depth of field and landscape that are the clear benefits of a location shoot. "The location is the whole thing," says Anderson, becoming excited. "Post-Mexican revolution, Federales hanging around and Americans lingering, looking for gold. It's such a great recipe for a story, but all born out of the location, which comes first. It probably made the studio nervous, but they couldn't have gotten half the great stuff they did without going to Mexico."

"The film does a lot really quickly," Anderson observes, as Bogart encounters Holt lounging on a bench. "It shows the venue, that Bogart's got no money and introduces his soon-to-be partner. The momentum is just going to keep going because Huston knows he has a lot to do before he gets to the film's main concern, which is, what happens when you actually get the gold?"

Anderson admires how every frame is packed with information and there is no waste at all. "It's economical and lean in the way it cuts from one thing to the next, but within that it's such a beautiful mess with stuff everywhere: cigarette smoke wafting into the frame, extras in the background, overhead fans turning. Everything is so alive."

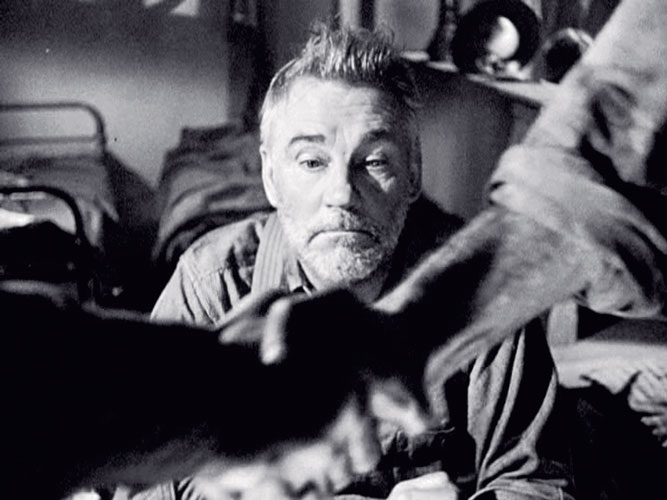

Bogart and Holt are soon left in the lurch for a few weeks' wages by a construction contractor, and seek shelter in a local flophouse. As they are handed bedding by a man with plastered hair, a mustache and suspenders, Anderson points at the screen. "All these bit parts—the guy handing them their bedding—are great. That's Huston, obviously in love with all the supporting players. He's not just after his stars being great. He clearly loved performers and got great ones, whether they were actors or non-professionals."

Heading to their cots, Bogart and Holt walk into a rattling monologue by another guest at the flophouse, Walter Huston, on the addictive nature of prospecting. Anderson listens intently and then gleefully echoes Bogart's words, "Not me!" as he insists that were he to strike gold he wouldn't fall into that trap, he'd only take what he set out to get. "Great," says Anderson, watching Bogart and the old man set up the tension that will drive the rest of the film. "That's it, right there, isn't it?"

But they still don't have the means to go prospecting, until Holt spots the contractor who cheated them. The three of them are soon tumbling over each other in a sloppy, fumbling bar brawl. "I like this because I don't remember fights from that period being this scrappy, so long and without music. Normally they're over in a punch or two and there's music along with it. Here, it's a full minute long. You'd think two against one they'd have a chance, but, boom." Anderson laughs as both Bogart and Holt are sent sprawling, before finally gaining the upper hand and taking their back pay, but not a penny more. "Very realistic."

Asked how he feels Huston is covering his shots, Anderson considers his answer. "John Huston never struck me as a film scholar, per se. Sierra Madre is just a play dressed up as an action movie, isn't it? His father was an actor so I think a lot of what he seems concerned with is how to best cover performance."

Nevertheless, as Bogart, Holt and Huston seal their deal to go prospecting together under Huston's tutelage, Anderson notes the composition of the scene and its final shot. Bogart and Holt stand opposite each other at the edge of the screen with Huston seated facing them, the back of his head protruding from below the frame. "It makes for a great reverse, coming up here on the handshake," Anderson points to the screen. "To me, the whole scene is set up for what the end of it is, right here," as the shot flips 180 degrees to find Huston's chin nearly resting on Bogart and Holt's clasped hands, looking up at them as though he'd seen such auspicious beginnings end on sour notes all too many times before. "I think it's pretty clear the director knew where he was going to end the scene, so he started it off in order to get his ending right."

Anderson gets excited as the threesome survives an attempted train robbery and begins its climb into the mountains, the momentum enhanced by the film's percussion-heavy, driving score. "God, I would trade all of my films just to be able to say I wrote this score. I'd hand them all off so when I got to the pearly gates I could say I wrote the score for Sierra Madre. Adventure films usually require good, strong music and I think we looked to Sierra Madre to steal some of its sound for There Will Be Blood."

Thinking they found real gold instead of the fool's gold it turns out to be, the two amateurs pour precious water on rocks to get a better look. "Water's precious," Huston scolds. "Sometimes it can be more precious than gold."

THE GOLD RUSH: Tim Holt, Humphrey Bogart and Walter Huston share

THE GOLD RUSH: Tim Holt, Humphrey Bogart and Walter Huston share

some beans on their expedition. The lighting from multiple sources

is theatrical, but seems totally authentic in a black and white film.

"There it is," Anderson says of the line that portends Bogart's eventual demise. "I tell you, it's horrible when you throw lines like that in—in a lesser actor's hands an alarm bell might go off, like, 'Oh, that's a warning of some kind.' But, when Walter Huston says it, and it's so true just as its own idea, it's not a movie moment anymore. It's something that transcends up into the clouds. Lines like that are guideposts, to keep you on course through the narrative."

While John Huston continues to plot his moral tale, it is again the extraordinary character work by the three actors that Anderson remains focused on, gleefully echoing Huston's lines as the film moves along. The three characters survive desert windstorms and steep climbs, caked in dirt, grit and grime, too tired to eat their beans when they pitch camp. "Well, that's just about as good as it gets," Anderson nods, fingers to his lips. "I don't remember seeing films of this period where they allowed people to get so realistically, incredibly dirty. Most Westerns, maybe there's a little bit of sweat they tried to get rid of but happened to be there. I have a feeling that by the time the dailies got back to Warner Bros. it was just too late to do anything about it. It adds such authenticity."

Soon enough, the prospectors have struck gold and the real story is set to begin as they divvy up the dust by the campfire, under the stars. There's a lantern and an apparent light source inside the open tent, but the actors do seem terribly well lit.

"I don't know what it is but there's something about black and white lighting that lets you get away with all kinds of things," Anderson says. "There's so many different sources here—there's some sort of moonlight thing they're doing, the lamp, the campfire. Maybe we're just used to films from this period but it seems authentic to me, although it's completely theatrical. I think that's just a product of the time. There's an old adage that if you do something in a period, you're taking a photograph of a photograph, you're not really recreating a period."

As the impact of striking it rich sinks in, the resulting tension between the men mounts, and what follows is essentially scene after scene of three guys gabbing around a campfire. "I can't tell you how he did it, and that's why John Huston is John Huston, but it doesn't feel repetitive," Anderson observes. "Each scene feels new. That's just something that God must give you a gift to do, because I couldn't do that. I'd be very curious what order they had to shoot it all in. For me, if I could at least do it in order, I'd know what I did the last time so I could desperately try and come up with something new."

Anderson watches intently as Bogart finally goes crazy with paranoia and shoots Holt, leaving him for dead. As Bogart deliberates to himself over what to do with the body, the camera follows him back and forth through the woods in a single take.

"Every time an actor has something emotional or difficult to take care of, you should try and narrow it down to one shot. The coverage is simple and it's easier to keep track of the work you're doing that way. The goal is then to get the performance as best as you can, rather than trying to get it from this angle and that angle, matching one to another. You're just piling struggle on top of struggle sometimes. You notice the long takes are sometimes the ones that are most performance-based. Huston's first priority, obviously, was the performances."

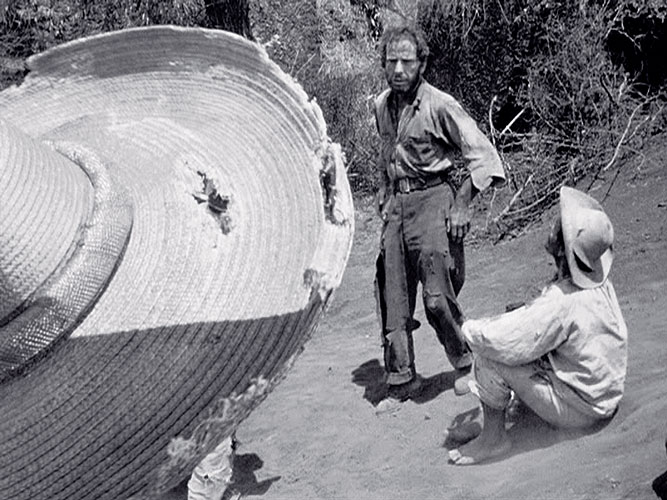

Having absconded with the gold of his two compatriots, caked in filth and out of water, Bogart doesn't notice as a group of banditos surround him as he desperately sucks down water from a dried-up riverbed. As he reaches for his empty gun, two bandits scurry casually to his feet and the leader turns toward him, his gold sombrero filling the lower left corner of the frame.

THE LAST STRAW: After absconding with the gold, a desperate

THE LAST STRAW: After absconding with the gold, a desperate

Bogart stops for water and is ambushed by Banditos who kill him

with a quick machete to the head. (Screenpull: © Warner Bros.)

Again, Anderson responds to the composition of the shot, shaking his head in appreciation. "That's pretty good directing, right there, and a realistic, straightforward death scene for one of the biggest movie stars of the time," he adds, as Bogart gets his. "A big, long adventure story, ended so quickly and economically with a machete to the head."

Thinking the gold is merely bags of sand, the bandits empty the dust on the ground and the wind takes it. When they try to sell the mules back in town, they are captured and executed, just as Holt and Walter Huston arrive in search of Bogart. "The whole thing from the beginning has been big-fish-eats-little-fish, leading to another eventual fish," Anderson says. "So there it is. The gold goes back to the mountains, the bandits go back to the ground, Bogart probably gets eaten by vultures. In the end they're all equal."

GIGGLE AND GIVE IN: Holt and Huston break into peals

GIGGLE AND GIVE IN: Holt and Huston break into peals

of laughter at the film's cosmic joke. (Screenpull: © Warner Bros.)

When Walter Huston realizes the fate of the gold, after spending 10 hard months finding it, the old man breaks into peals of laughter at the great joke played on them by "the Lord or Fate or Nature, whatever you prefer." "That's life's answer right there," Anderson says. "Giggle and give in, Bob Altman used to say. Giggle and give in. No matter how tense things get, there is always relief with a laugh around the corner in this film. It gives the sense of realism, even if it's ultimately more theatrical. It's a movie after all, so it can't have no laughs, and I suppose I'm always looking for one. My favorite thing is to sit with an audience and hear it laugh. It's a euphoric experience. In the end, we've been taken for a ride just as we should be, just in the way John Huston is encouraging us to look at life."