BY DAVID THOMSON

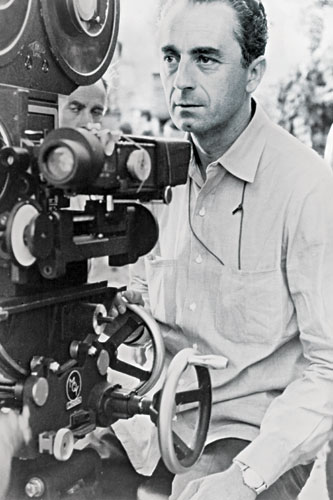

Antonioni (left); Bergman (right).

Antonioni (left); Bergman (right).In the late 1950s and early '60s, as ever in our history, there was ample reason for pessimism. No matter that America and the Soviet Union were led by veterans of terrible wars, the Cold War was advancing. Prodigious bombs were being tested in the atmosphere. Berlin was already identified as one flash point, the new Cuba might be another. And we were having to learn how to find Indochina on our maps. Even the American cinema, loyal to optimism and positive thinking, to energy and goodwill, was taking on the large, dark subjects—On the Beach, The Diary of Anne Frank, Judgment at Nuremberg. And Dr. Strangelove was coming—a satire on the end of the world.

But in the cinemas of the world, and this certainly includes America, I can think of four far smaller, quieter films from the same years that embodied the prevailing anxiety in ways that moved many viewers—not just for the quality of the films, but because these pictures showed us a new way of looking at film itself. I am thinking of The Seventh Seal (1957), Wild Strawberries (1957), L'Avventura (1960), and La Notte (1961), for obvious reasons. At the end of July, their directors, Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni, died on the same day. No one aware of film has been untouched by these two artists

The Seventh Seal was obviously apocalyptic. In a Dark Age beset by plague, cruelty and terrible religious persecution, Death seeks out a knight. It is time, says the shrouded figure, but the knight loves life and reckons to extend his chance by challenging Death to a game of chess. Though we also meet a blessed version of the holy family in whom hope still abides, as the game plays out, we get a chance to see how bleak the prospects for life are. There's a similar pattern in Wild Strawberries. Isak Borg is an old man. His life seems to be a series of achievements, yet he is beset by gloom and nightmares. He has to travel to receive an honorary degree and the journey becomes the framework for flashbacks that disclose his failure, his shame and his regret. But along the way he meets a girl (played by Bibi Andersson, the same actress who is the mother in The Seventh Seal). Her smile and her hope offset Borg's nagging dreams. Bergman didn't mention the Bomb, the concentration camps or the ordeals of 1957. Yet nearly every viewer of the film—and it was a worldwide success—felt those larger things in the air. Equally, in Borg's disillusion, you could read the failure of the larger life of the mind—yet Wild Strawberries was an inward film, about dreams, psychology and meditation, and it is said there is no escaping those states. At first, viewers remarked on Bergman's pessimism because the grave tone was new and stark and because he had found a black and white photography that seemed etched on the soul. But even within the darkness of the film, life flourishes, and always will as long as there is a taste fresh enough to enjoy the new season's wild strawberries.

The films of Michelangelo Antonioni were even more introspective. In L'Avventura, a group of friends go off for a day, cruising the offshore islands. Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) and Anna (Lea Massari) are lovers. Anna's friend Claudia (Monica Vitti) is also there. But on the island, Anna's unease—palpable from the outset, though never laid out as a story element—rises to a point where she disappears, or no longer exists.

You can't do that in a movie, said some audiences—and the film was booed, first at Cannes in May 1960. Why not? Antonioni seemed to counter. Don't we forget even people we love as time goes by? The disappearance of Anna is absorbed by the film. There is not a prolonged police investigation into the lost person. That's how America would have played it (that's what happened in the same year in Psycho when Marion Crane vanished). Instead, as if by gravity, Claudia becomes Sandro's lover, and learns to see the weakness in him that might have warned Anna away.

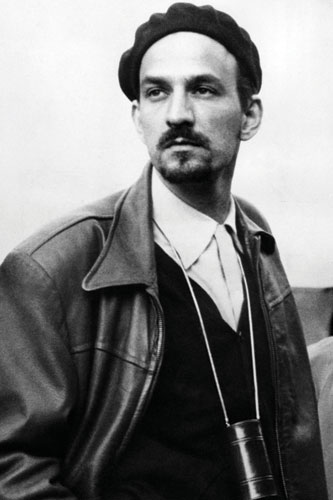

NO PICNIC: Antonioni elicits his famous alienated glance

NO PICNIC: Antonioni elicits his famous alienated glance

from Jeanne Moreau as a wife whose marriage is falling

apart in La Notte (1961). (© Photofest/UA)In a way, nothing happens, except that love fades like the daylight. In Antonioni's next film, La Notte ("The Night"), Giovanni (Marcello Mastroianni) and Lidia (Jeanne Moreau) seem well-suited in marriage—until we notice how they look askance at each other. Famously, it's an alienated glance, a looking away, that Antonioni invented—or recognized. The husband is an ambitious and insecure novelist. There are no children. She wants to be in love, yet in the course of a day and a night (and the grim party that brings up the dawn) we wonder whether the marriage can or should endure. There is another woman for a moment—Monica Vitti, again—but the film cannot persuade itself, or her, that she could "save" or change Giovanni. The night of the title is an emotional pessimism that has come as an eclipse in a society that wants to believe in love still, but which is too wearied by its own lack of faith or fidelity.

I don't mean to say that the world fell into worship of Bergman or Antonioni, or even that it should have. Film works in a great variety of ways and while it was plain that these two were part of a trend toward inwardness and the novelistic, they were also anchored in gloom, depressiveness and anxiety, no matter the epiphanies felt in the face of Bibi Andersson or the way Jeanne Moreau enjoys the afternoon sun as she walks aimlessly in Milan. But the sense of these films having an unusual responsibility to context—to thinking at large, to seeing and working out meaning—was backed up by so much else in world cinema.

I'm thinking of Godard and the French New Wave, of Satyajit Ray and the recent discovery of Japanese cinema, of films from Poland—like Wajda's Kanal and Ashes and Diamonds. Add in the re-emergence of Buñuel, the purple patch for Fellini, and even a resurgence of film vitality in Britain (The Servant, Tom Jones, Darling).

As several observers have mentioned already in discussing Bergman and Antonioni, they represent that moment in history when "movies" became film, or cinema, or art, or something so challenging and beautiful that you were revisiting the film for the next few days and weeks. Or for the rest of your life. And one thing united all these films—the indisputable fact that they had been made by a person, a director, an auteur. Although such an attitude cuts against the Hollywood grain, nowhere was it more appreciated than in America where a new generation was desperate to be taken seriously as filmmakers. It reaches from Arthur Penn to Woody Allen, from Altman to Scorsese, from Francis Ford Coppola to Paul Thomas Anderson. Ultimately, Bergman was presented with the DGA's Lifetime Achievement Award in 1990.

The recent deaths allowed one to recall the impact that Bergman and Antonioni had on film discourse. I don't just mean suitable subject matter and camera style, black and white resonance and the evocation of heartache in close-ups. I mean the way a new generation of critics talked about the movies and the way our schools started to teach it. I would guess that in the history of film study, the most frequent subjects of seminars have been Ingmar Bergman and Alfred Hitchcock. And that's a very telling imprint of how we long to maintain different traditions of inwardness and outwardness.

Ingmar and Michelangelo believed that there was and is no protection, that a great filmmaker goes to work out of the dread that never vanishes. That he is fit for nothing else. The blood of all our wounds, as well as the epiphanies of our brief lives, can be found in Wild Strawberries, Persona, Cries & Whispers, Fanny and Alexander, Smiles of a Summer Night, Sawdust and Tinsel, and throw in another four or five of your favorites. And we might add that Bergman did it as recently as Saraband, shot after years of retirement and old age, and filled with those churning feelings of personal and metaphysical unease that had always scarred him.

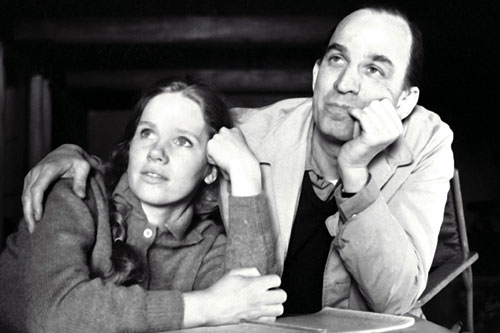

SOULMATES: Liv Ullmann was Bergman's muse and collaborated with

SOULMATES: Liv Ullmann was Bergman's muse and collaborated with

him on 10 films including Hour of the Wolf (1968). (© Photofest/Lopert)And I am one of those who saw or felt the last moments of Antonioni's The Passenger, as the camera slid out of its room at the Hotel de la Gloria, somewhere in Spain, and thought that I had never seen a film that so captured the eternal mystery of small incidents, let alone the hinge of dusk when the lights come on.

There are many other cultural lessons in the achievement of Bergman and Antonioni. It's probably true that the collected budgets of Bergman's films (60 or so) did not exceed the cost of one Brett Ratner film. What does that mean, finally? Well, directors cannot hide behind "spectacle" if a portion of the audience still believes that they have never seen anything as shattering as, say, the face of Liv Ullmann as she changes her mind.

There's another lesson, which is that we may try to tidy our stories too much—sending the audience home on a happy ending or a big bang in which everyone dies. Whereas an Antonioni film leaves us with questions like what should Claudia do at the end of L'Avventura; was there really a murder in Blowup; or what has this film The Passenger been about?

Ambiguity was seldom talked about in the golden age of Hollywood—it had no place in the business equation. But America's assurance has changed in nearly every field, from military power to narrative authority, and we are becoming more familiar with ambiguity all the time. What was regarded as unhappiness in Bergman or Antonioni may be no worse than those feelings. If you are going to explore the innermost human mind, expect to find as much doubt as certainty. And once you've had a taste of ambiguity, it's a hard habit to lose. Thus, consider this: Is Michael Corleone a positive or a negative force in his America? If the answer is beginning to be "both," then we are coming to terms with ourselves—and it's clear how much we have absorbed from the age of these two great masters.